Latin Church in Turkey

Levantines in Turkey or Turkish Levantines, refers to the descendants of Europeans who settled in the coastal cities of the Ottoman Empire in order to be engaged in trade especially after the Tanzimat Era. Their estimated population is around 1,000.[1] They mainly reside in Istanbul, İzmir and Mersin. Anatolian Muslims called Levantines Frenk (first used for French then for all non-Orthodox Europeans) and Sweet Water Freng (due to their high-standard life style) in addition to Levanten.

The origin and meaning

The term Levant comes from the French language. It means 'rising' (sun, i.e. East; the Latin word 'orient' had the same original meaning) in French. Even though it has been used for Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel, it was used to refer to 'the sea in the east of Italy'.[2]

Over time the term Levant was widened. During the Byzantines and the first years of Ottomans, the term was used to refer to Western Mediterraneans such as Italians, Catalans and French. During 18th and 19th centuries, the term also was used for settlers that came from Central and Northern Europe.[3]

History

First Levantines

Levantines began to settle in Constantinople in 991 when they were given some trade privileges from Byzantines. They settled in Istanbul peninsula and Galata. Pera was the settlement of Genoese and Venetians. In the later years the traders from Amalfi and Pisa were given these privileges.[4]

After the fall of the Roman Empire, there has been increasing differences between Latin-Western and Greek-Eastern Christians. According to Ortaylı, first significant Levantines were Genoese merchants who had traded with Byzantines.

The second significant group of Levantines were Venetians. At that time, Eastern Roman power was decreasing while Ottomans were gaining ground. Venetian merchants were traded across Mediterranean during Byzantine Era and built Galata Tower. Venetians and Ottomans were also allies against Genoese-Byzantine alliance.

Genoese were more active in Anatolian Peninsula while Venetians were powerful in Aegean islands. There were also several Italian city-states that were active in and around Anatolia. The Crusades also played an important role in the lives of Levantines.

The cities chosen by Levantines were settled in important trade routes and they were safe places. Istanbul was the center of the Ottoman Empire and Izmir was a safe city located within a gulf and feeding Istanbul with its potential. Izmir was also a center for fresh produces such as grape, fig, olive and okra. Consequently, Venetians and French began to settle in Izmir after Genoese traders. Over time Italian influence began to decrease and British, Dutch and German merchants increased their ties with Anatolian coast. They also married other non-Catholic and non-Protestan Christians, especially Greek Orthodox.

Capitulations and Tanzimat

French merchants began to play an active role in Levant trade routes after French-Ottoman alliance. Ottomans gave safe passage for French traders and approved the capitulations for the French state.

Especially after the Tanzimat Era, the Capitulations were approved for other European states. Consequently, there was a significant increase in the numbers of Europeans who came to Ottoman territories, especially in coastal cities. European traders were not Ottoman citizens, so they did not have to pay taxes nor were they obliged for the army. Therefore, Europeans became wealthier over time.[5] In addition, they became pioneers in industrialization and Western Art.

20th century

Ottoman Empire fought against the British, French and Italians during World War One. Victorious states of World War One compelled Ottoman government to sign the Treaty of Sèvres. The United Kingdom, Italy and France were among the occupants in Anatolia. After the independence of Turkey, there has been negative public opinion towards Levantines because of allegations that Levantines had cooperated with the Allies. After the Great Fire of Smyrna, most of Levantines left Smyrna (now Izmir) and only a few came back.

After the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) came into power after 1908 Revolution, Levantines began to be affected by policies of Turkish nationalists. Levantines were also not happy against increasing Greek presence in the city of ISmyrna. The Greek occupation in Smyrna weakened their power in the city economically. In addition, their economic interests suffered due to the World War One and in the first years of Turkey. The Great Depression affected Levantines very much. They quit their jobs and began to leave Turkey due to high maintenance costs. Their settlements became government property.

There has been significant problems in Turkish economy after Levantines and Greeks left the country. Turkey faced exportation problems. Most of exports remained at the hands of local Turkish villagers. However, Turkish government left all capitulations of Levantines in order to break the monopoly for Turkish entrepreneurs.

Present

Today, numbers of Levantines are not clear. It is estimated that there are about 100-150 Levantines in Izmir. Another estimate put the number as hundreds.[6] However, the number may be higher because of assimilation policies of Turkish nationalist-Kemalist governments, conversions to Islam because of the fear after the Greek and Armenian Genocides, or intermarriages. In the documentary about the Levantines of Izmir (Bazıları Onlara Levanten Diyor), Levantines call themselves 'Christian Turks' and they say they are not happy to be called Levantines.[7]

Less than one hundred Levantine families are left in Istanbul. However, the number is not clear. Istanbul pogrom has deeply effected Levantine population as much as Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. After Istanbul Pogrom, it is known that most of Levantines fled to France, the United States and other Western European countries.[8] Most of them have second passports or they only have one passport which belongs to the country of their ancestors. Many young Levantines prefer to go abroad rather than staying in Turkey.[6] The remaining Levantines or their scions hold some meetings in Istanbul to protect their heritage and find their past.[9]

There are also several Levantines left in Mersin and Iskenderun. There are still some families in Mersin who are the descendants of Europeans: Levante, Montavani, Babini, Brecotti, Şaşati, Vitel, Talhuz, Antoine-Mirzan, Nadir, Rexya, Soysal, Hisarlı, Kokaz, Daniel, Kokalakis, Yalnız.[10] Mersin Catholic Church is still active in the city. Some of the members of the church are still Maronites.

Levantine population in the past

Istanbul (Constantinople)

The first Levantines in Ottoman territories lived in the Pera (Beyoğlu) and Galata districts of Constantinople, now known as Istanbul. The most populated time of Levantines was during the 19th century with 14,000 people.[3]

Izmir (Smyrna)

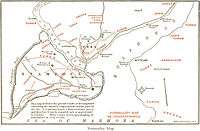

In 1818, Traveller William Jowett described the distribution of Smyrna (now Izmir)'s population as: Turks 60,000, Greeks 40,000, Jews 10,000, Latins 3,000, Armenians 7,000.[11]

In 1856, Ottoman state allowed Christians to have possessions. Consequently, the number of Levantines in Smyrna began to increase dramatically. The number of non-Muslim population was 15,000 in 1847 while it has increased to 50,000 in 1880. Smyrna became an Levantine city and began to called as 'the capital of Levant', 'the pearl of Levant', 'the Marseille of Anatolian coasts' or 'a Marseille on the coast of Minor Asia'.[12]

The sources of 19th century estimates the population of Levantines between 16,000 and 25,000. The minimum proportion is 8% of Smyrna's population while the maximum estimate is 17%.[13]

Non-Muslim peoples of Smyrna lived in different quarters. There was one each quarter for Turks, Greeks, Armenians, Jews, and Frenks (Levantines).[14] 1914 population estimate indicates; 378,000 Muslims and 217,686 Orthodox Christians.[15]

Mersin

The Çukurova region gained importance after the planting of cotton that came from Americas. Therefore, the cities of Adana and Mersin began to attract Europeans. Levantines especially began to live in Mersin, especially after the 19th century, European entrepreneurs created the 'Frenk Quarter' in Mersin. The population table is below during Ottoman times;[10]

- In 1879, 625 Muslims, 147 Greeks, 37 Armenians and 50 Catholics were living in Mersin.

- In 1891, 5000 Muslims, 2700 Greeks, 860 Armenians and 260 Catholics were living in Mersin.

Culture

Language

There are some words effected Turkish language such as "racon" (show-off ) and "faça" (face).[16]

Religion

Levantines are Western Christians. They are separated by their sects. Most of them are Catholics while there are Protestants (Anglicans and Baptists) among them.

Levantines have their own churches in some cities. They are named according to their ethnicity or sect such as Alman Protestan Kilisesi (German Protestant Church) or İzmir Baptist Kilisesi (Izmir Baptist Church). Churches in Izmir are sometimes called as 'Levantine Church'.

Churches

Church of St. Anthony, Mersin

Church of St. Anthony, Mersin- Crimea Memorial Church, İstanbul

Education

There are French, Italian, German and Austrian schools in Istanbul and Izmir. However, most of students are Turks. Schools are counted as private school, however.

Schools

- Saint Benoît French School, İstanbul

Italian School, İstanbul

Italian School, İstanbul- St. George's Austrian High School, İstanbul

Architecture

One of the oldest buildings of Levantines is Galata Tower in Istanbul. It was in the European quarter until 1453. After the fall of Istanbul, Venetians surrendered the tower to Ottomans.

Izmir is the most important city for the remaining Levantine architecture. Karşıyaka (Courdelion), Bornova (Bournabad) and Buca (Boudja) were known as the center of Levantines in Izmir until Turkish Independence War. Levantines left tens of buildings in Izmir, most of them are mansions once belong to European merchant families. Some of them are below:[17]

| Name | Nationality | Place |

|---|---|---|

| Aliotti Mansion | Italian | Bornova |

| Lochner Mansion | German | Bornova |

| Penetti Mansion | Italian | Karşıyaka |

| Van der Zee Mansion | Dutch | Karşıyaka |

| De Jongh Mansion | British-Dutch | Buca |

| Rees Mansion | British | Buca |

| Baltazzi Mansion | Italian | Buca |

| Forbes Mansion | British | Buca |

| Giraud Mansion | French | Bornova |

| Peterson Mansion | Scottish | Bornova |

| Edwards Mansion | British | Bornova |

| Bardisbanian Mansion | Armenian | Bornova |

| Belhomme Mansion | British | Bornova |

| Whittall Mansion | British | Bornova |

There are also some inns and konaks in Mersin that can be seen.

Notable people

- Sir Alfred Biliotti - Italian soldier and archeologist

- Livio Missir di Lusignano - Italian historian

- Giuseppe Donizetti - Italian musician

- Giovanni Scognamillo - Italian writer

- Count Abraham Camondo - Jewish-Italian financier, philanthropist and the patriarch of the Camondo family

- Lucien Arkas - French businessman of Arkas holding company

- Maria Rita Epik - Italian musician

- William Buttigieg - Maltese-British the consul general of Izmir

- Caroline Giraud Koç - French businesswoman

References

- Levanten kültürü turizme açılıyor haberler.com (12.08.2013)

- www.etymoline.com (13.08.2013)

- Levanten kavramı ve Levantenler üzerine bir inceleme Archived 2012-06-19 at the Wayback Machine Raziye OBAN (ÇAKICIOĞLU)-Türkiyat Araştımaları Dergisi(12.08.2013)

- Levanten Kavramı ve Levantenler üzerine bir inceleme, pg. 345, Raziye OBAN ÇAKICIOĞLU

- Atatürk döneminde Maliye Politikaları Archived 2013-04-18 at the Wayback Machine Maliye Bakanlığı

- http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/iki-sehrin-levantenleri-158881

- http://arsiv.sabah.com.tr/2005/10/02/cpsabah/gnc118-20051002-102.html

- http://blog.writeweller.com/1996/05/lost-levantines-of-istanbul.html

- http://www.dailysabah.com/nation/2014/11/04/levantine-legacy-in-the-spotlight-at-istanbul-event

- Mersin Levanten binaları üzerine bir inceleme, Çukuova Üniversitesi Yüksek Lisan Tezi, Gülizar AÇIK GÜNEŞ(28.08.2013)

- İzmir Levantenleri üzerine inceleme, Muharrem Yıldız, Turan Strategic Research Center, Year:2012, Volume:4, Number:13, Page:43

- İzmir Levantenleri üzerine inceleme, Muharrem Yıldız, Turan Strategic Research Center, Year:2012, Volume:4, Number:13

- The Image of the Levantines as Portrayed in the late 19th Century Travel Literature Archived 2017-04-23 at the Wayback Machine Achilleas Chatziconstantinou (12.08.2013)

- Erkan Serçe,İzmir ve Çevresi Nüfus İstatistiği 1917, Izmir, 1998, pg.5

- Erkan Serçe,İzmir ve Çevresi Nüfus İstatistiği 1917, İzmir, 1998, pg.6

- http://www.dailysabah.com/feature/2014/03/28/an-exotic-community-in-the-ottoman-empire-the-levantines

- http://www.geziko.com/blog/izmirin-tarihi-levanten-evleri/