Hackney, London

Hackney is a district in East London, England. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hackney, forming around two thirds of the area of the modern London Borough to which it gives its name. It is 4 miles (6.4 km) northeast of Charing Cross. Historically it was within the county of Middlesex.

| Hackney | |

|---|---|

Cassland Road and Cassland Crescent, South Hackney | |

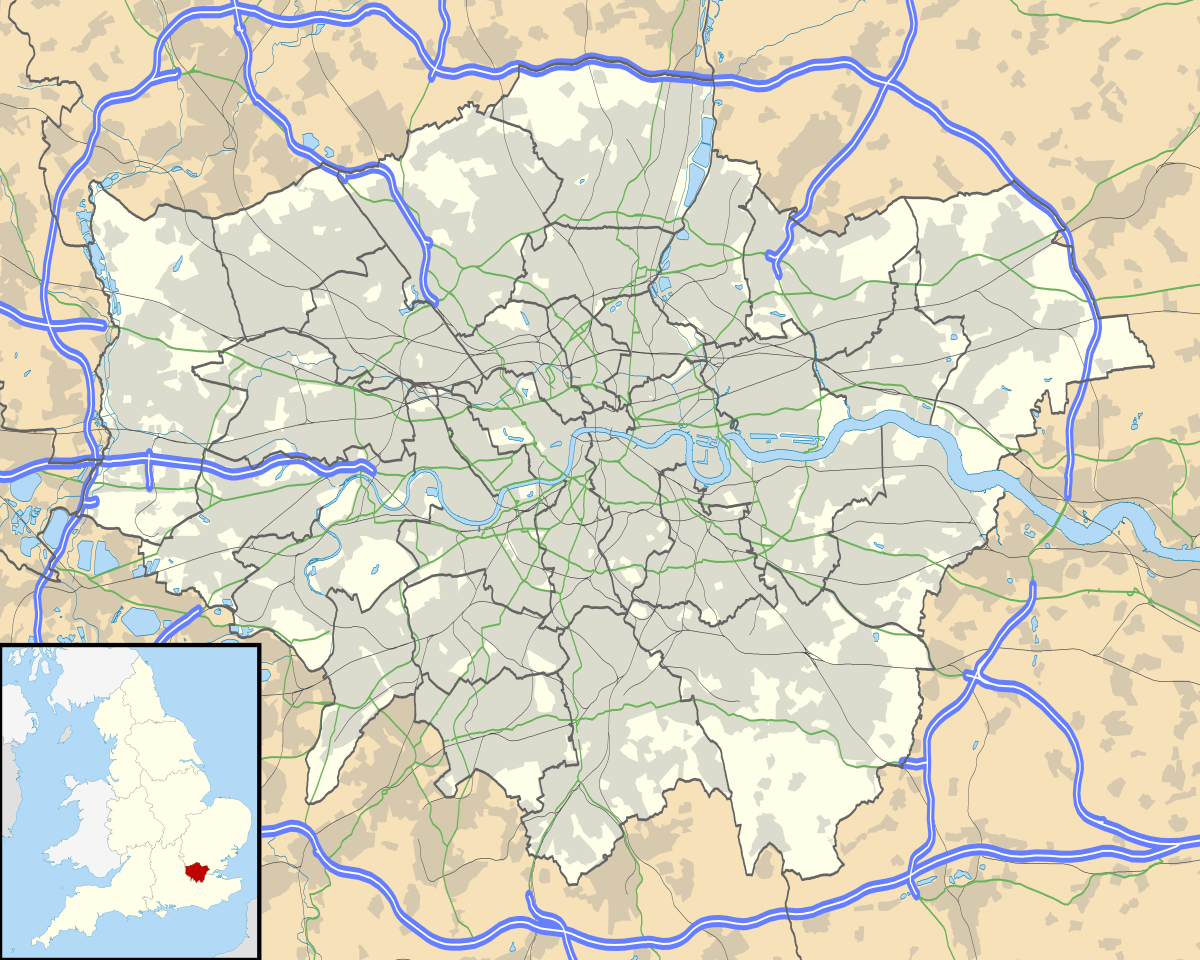

Hackney Location within Greater London | |

| OS grid reference | TQ345845 |

| • Charing Cross | 4 mi (6.4 km) SW |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | E5, E8, E9, N1, N16 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

In the past it was also referred to as Hackney Proper to distinguish it from the village which subsequently developed in the vicinity of Mare Street, the term Hackney Proper being applied to the wider district.[1]

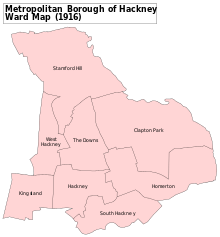

Hackney is a large district, whose long established boundaries encompass the sub-districts of Homerton, Dalston (including Kingsland and Shacklewell), De Beauvoir Town, Upper and Lower Clapton, Stamford Hill, Hackney Central, Hackney Wick, South Hackney and West Hackney.

Governance

Hackney was an administrative unit with consistent boundaries from the early Middle Ages to the creation of the larger modern borough in 1965. Hackney was based for many centuries on the Ancient Parish of Hackney, the largest in Middlesex.

It is not known exactly when the parish formed, it may have initially been part of the parish of Stepney, as Hackney was initially a sub-manor of Stepney. Irrespective of whether the parish was independent from the introduction of the parish system, long before the Norman Conquest,[2] or whether it was an early sub-division of Stepney parish, the parish would have been based on the boundaries of this manor of Hackney at the time it was created. Any boundary changes to the manor after around 1180 would not be reflected in changes to the parish boundaries as, across England, they became fixed at around that time, so that boundaries could no longer be changed at all, despite changes to manorial landholdings - though there were some examples of sub-division in some parishes.[3]

The manorial system in England had largely broken down in England by 1400, with manors fragmenting and their role being much reduced.

Parishes in Middlesex were grouped into Hundreds, with Hackney part of Ossulstone Hundred. Rapid Population growth around London saw the Hundred split into several 'Divisions' during the 1600s, with Hackney part of the Tower Division (aka Tower Hamlets). The Tower Division was noteworthy in that the men of the area owed military service to the Tower of London - and had done even before the creation of the Division.[4]

The Ancient Parishes provided a framework for both civil (administrative) and ecclesiastical (church) functions, but during the nineteenth century there was a divergence into distinct civil and ecclesiastical parish systems. In London the Ecclesiastical Parishes sub-divided to better serve the needs of a growing population, while the Civil Parishes continued to be based on the same Ancient Parish areas.

The Metropolis Management Act 1855 merged the Civil Parishes of Hackney and Stoke Newington under a new Hackney District. This proved very unpopular, especially in more affluent Stoke Newington and after four unsuccessful attempts the two parishes regained their independence when they were separated by mutual consent under the Metropolis Management (Plumstead and Hackney) Act of 1893.[5]

The London Government Act 1899 converted the parishes into Metropolitan Boroughs based on the same boundaries, sometimes with minor rationalisations. In 1965, Hackney merged with Shoreditch and Stoke Newington to form the new London Borough of Hackney.

Prior to 1994, a small part of Victoria Park was part of Hackney, but a minor boundary alteration was made[6] so that the whole park came under the control of Tower Hamlets.

Place name origin

The first surviving records of the place name are as Hakney (1231) and Hakeneye (1242 and 1294). The name is Old English, but the meaning is not certain. It seems clear however that the ‘ey’ element refers to an island or a raised or otherwise dry area in marshland. The term 'island' in this context can also mean land situated between two streams.[7]

The 'island' may have been beside the Lea or perhaps near the confluence of the Hackney Brook and Pigwell Brook in the Hackney Central area.

The Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names examined various interpretations of the place name and favoured the interpretation that Hackney means ‘Haka’s island’, with Haka being a notable local person The Dictionary suggests that the ‘Hack’ element may also derive from:

- The Old English ‘Haecc’ meaning a hatch – an entrance to a woodland or common.

- Or alternatively from ‘Haca’ meaning a hook, and in this context, a bend of the river.

Given the island context, the ‘hatch’ option is unlikely to be correct, so the favoured 'Haka's Island' or the 'Island on the bend' seem more likely.

History

Pre-Roman

Hackney is a mostly low-lying area in proximity to two rivers, the Lea and the Hackney Brook. This would have made the area attractive for pastoral and arable agriculture, meaning most of the area is likely to have been deforested at an early date. There is archaeological evidence for settlement and agriculture as far back as the Stone Age.[8]

During the late Iron Age, the area was part of the territory of the powerful Catuvellauni tribe.

Roman

There will have been a network of probably minor, local roads in Hackney before the Romans conquered southern Britain after 43AD, but the areas proximity to the provincial capital, Londinium, meant that it was soon crossed by two large long-distance routes. The first was Ermine Street (modern A10) which emerged from Bishopsgate and headed north to Lincoln and York. The second was a route which branched off Ermine Street just outside Bishopsgate and headed SW-NE across Hackney, across the Dalston, Hackney Central and Lower Clapton areas to cross to the Lea on its way to Great Dunmow in Essex.[8][9] This crossing appears to have crossed the Lea 168 metres south of the Bridge at Mandeville Street near Millfields Road (sometimes known as Pond Lane Bridge).[10] Three Roman sarcophagus burials have been found, two of stone and one of marble. These, particularly the marble example indicate a high status settlement of some sort. The stone examples had a coin hoard found nearby.

Anglo-Saxon

The area around Millfields Park, Lower Clapton is sometimes described as the site of a battle between Aescwine, reputed first King of Essex, and Octa, King of Kent.[11] The ford over the Lea is referred to in the (much later) accounts of the battle. Historical records describing this period are extremely sparse, so the historicity of the battle, and even Aescwine himself is disputed.

The place name Hackney is Old English, so was probably first applied in this era.

Hackney was part of the territory of the Middle Saxons, a people who seem not to have formed a province of the East Saxons, albeit not part of their core territory. The area was a part of the huge manor of Stepney, an area owned by the Bishop of London, and its great size and proximity to the City means it may have been part of the grant of land made when the Diocese of London (The East Saxon Diocese), was re-established in 604 AD.

Later, the Middle and East Saxon area would become subject to various other Kingdoms, culminating in Wessex as it led a long process to unite England as it rolled back the partial Viking conquest of the country. A coin of Egbert of Wessex was found on Stamford Hill. The Kings of Wessex divided their kingdom into shires, with Hackney becoming part of the shire of Middlesex, an area named after the Middle Saxons.

After the Conquest

The Domesday Book of 1086 covered England at manorial level, so Hackney is only assessed as part of Stepney, of which it was a sub-manor. The landscape at this time was largely agricultural, Domesday returns for Middlesex indicate that it was around 30% wooded (much of it wood-pasture), about double the English average.[12] Hackney would have had a lower proportion than the county as a whole, consisting of mostly lower land, close to rivers that made it more attractive for farming. The proportion of woodland in England decreased sharply between the Conquest and the Black Death[13] due to the pressure of a rapidly increasing population, and the same pressures would have been experienced here.

Post-medieval

From the Tudor period onwards, the various settlements in Hackney grew as wealthy Londoners moved to what they saw as a pleasant rural alternative to living in London; but which was, nonetheless close to the capital - in some ways it was comparable to a modern commuter town. A number of royal courtiers lived in Homerton, while Henry VIII had a palace at Brook House, Upper Clapton, where Queen Mary took the Oath of Supremacy.

The main ‘Hackney Village’ grew much larger than the others, in 1605 having as many houses as Dalston, Newington (ie West Hackney), Kingsland and Shacklewell combined.[14]

In 1727 Daniel Defoe said of the hamlets of Hackney

All these, except the Wyck-house, are within a few years so encreas'd in buildings, and so fully inhabited, that there is no comparison to be made between their present and past state: Every separate hamlet is encreas'd, and some of them more than treble as big as formerly; Indeed as this whole town is included in the bills of mortality, tho' no where joining to London, it is in some respects to be call'd a part of it.

Urbanisation

The growth of the East End of London was stimulated by the building of Regent's Canal between 1812–6, with construction work on a new town at De Beauvoir beginning in 1823 and continuing through the 1830s. The arrival of the railways, around 1850, accelerated the spread of London and the expansion of the existing nuclei, so that Hackney was almost entirely built up by 1870.

Blitz

Hackney was badly affected by wartime bombing that left the area with 749 civilian war dead,[15] with many more of its citizens injured or left homeless. The bombing campaigns of 1940-41 was followed by lighter, infrequent raids later in the war and the ‘vengeance weapons’, the V-1 'doodlebugs' and V-2 rockets in 1944–45. Many other Hackney residents were also killed on active service around the world. Notable buildings destroyed by bombing included Tudor-era Brooke House[16] in Upper Clapton and West Hackney church.

Olympics

.jpg)

Hackney was one of the host areas when London staged the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, with three venues falling within its part of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park:

- Copper Box Arena hosted events including Handball, Modern Pentathlon and Goalball. This 7,000 seat multi-sport venue is still used for community and elite sport.

- The Riverbank Arena was a temporary venue which hosted Field Hockey during the Olympics, and Football 7-a-side and Football 5-a-side during the Paralympics.

- London Olympics Media Centre. The facility is still in use and now known as Here East.

Affordable housing

Hackney's solution to affordable housing has been able to put more affordable housing on the market by making use of inclusionary practices.[17] This district built a significant number of affordable units and subsidised them with market rate units.[17] In Hackney about half of the new units are affordable. In an effort to avoid displacing current residents, construction was completed in phases.[17]

Geography

The outline of Hackney's traditional boundary resembles a right-angled triangle with the right-angle in the SW and the Lower Lea Valley, running NW-SE forming the hypotenuse. The western boundary is based on the N-S axis of the Roman A10, though the sub-district of De Beauvoir Town lies beyond it, as do small areas of Dalston and Stamford Hill.

The district's southern boundary follows the Regents Canal-Hertford Union Canal in part, and for the remainder marches a little to the north of it, with Victoria Park also forming part of the southern boundary.

The highest points around Stamford Hill and Clapton Common are over 30m AOD, with the lowest areas being along the River Lea. The Hackney Brook was the largest natural internal watercourse, entering Hackney in the NW, at the foot of the southern foot of Stamford Hill and exiting in the south-east, however this watercourse was fully culverted in the 19th century.

The boundaries of Hackney take in the sub-districts of Homerton, Dalston (including Kingsland and Shacklewell), De Beauvoir Town, Upper and Lower Clapton, Stamford Hill, Hackney Central, Hackney Wick, South Hackney and West Hackney.

The Lea and Hackney Marshes are underlain by alluvium soils; and the higher ground between Homerton and Stamford Hill is formed on a widening bed of London Clay. Brickearth deposits are within tongues of clay extending beneath Clapton Common, Stamford Hill and Stoke Newington High Street. The centre and south western districts lie on river terrace deposits of Taplow Gravel. The area around Victoria Park and Well Street Common lie on flood plain gravel.[18]

Open spaces

Open spaces in Hackney include:

- Clapton Common[19]

- Hackney Downs

- Hackney Marshes

- Mabley Green

- London Fields

- Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (part)

- Springfield Park and Spring Hill Recreation Ground

- Stoke Newington Common, originally known as Cockhangar Green, and part of Hackney rather than Stoke Newington proper

- Victoria Park (outside of Hackney, but forming part of the southern boundary)

- Well Street Common

- West Hackney Recreation Ground

- Hackney City Farm

Transport

Rail

Hackney is served by six stations, including by the London Overground at Hackney Central railway station, and it is named after the central area of Hackney, as well as Hackney Downs. Central was open by the North London Railway opened as Hackney on 26 September 1850, to the east of Mare Street. It closed on 1 December 1870 and was replaced the same day by a station to the west of Mare Street, designed by Edwin Henry Horne and also named Hackney. This station passed in due course to the London & North Western Railway and later on to the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, which closed the entire North London Line east of Dalston Junction to passenger traffic in 1944.[20] Downs was opened on 27 May 1872 when the Great Eastern Railway opened the first part of its new line from Enfield Town to Stoke Newington.[21][22]

A pedestrian link between Hackney Downs and Hackney Central stations was opened in 2015 by London Overground Rail Operations. Until Hackney Central's closure in 1944, a passenger connection had linked the two stations. However, when Hackney Central re-opened in 1985, the footway was not reinstated and passengers transferring between the two stations were obliged to leave one and walk along the street to the other, until the link was rebuilt.[23]

Hackney Wick opened on 12 May 1980[24] by British Rail on the re-routed line which bypassed the site of the former Victoria Park station as part of the CrossTown Link line.

In 1872, London Fields railway station was opened by the Great Eastern Railway.[25] It closed in 1981 due to a fire, repairs were eventually carried out and the station reopened in 1986.[26]

In February 2006, a Docklands Light Railway (DLR) report called Horizon 2020 was commissioned, which suggested that the DLR be extended to Hackney Central from Bow Church via Old Ford and Homerton, taking over the old parts of the North London Line to link up with Poplar and Canary Wharf.[27]

Buses

Hackney is served by a large number of London Buses routes, 26, 30, 38, 55, 56, 106, 149, 236, 242, 253, 254, 276, 277, 388, 394, 339, 425 and 488 as well as the D6, and W15. Hackney is also served by the London night bus network with routes N26, N38, N55 and N253 all running in the area.[28] Route N277 also serves here when the 277 route was withdrawn between Dalston and Highbury Corner and the N277 was retained.[29]

References

- "The National Gazetteer of Great Britain and Ireland". 1868. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- Encyclopaedia Brittanica 1993, the article describes how the Parish system in England was already very old at the time of the Norman Conquest

- History of the Countryside by Oliver Rackham, 1986 p19

- The London Encyclopaedia, 4th Edition, 1983, Weinreb and Hibbert

- "Stoke Newington: Local government | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- "The Hackney and Tower Hamlets (London Borough Boundaries) Order 1993". www.legislation.gov.uk.

- The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names, Eilert Ekwall, 1990

- https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/planning/apa-hackney-pdf/

- http://www.lamas.org.uk/images/documents/Transactions59/039-060%20Crown%20Wharf.pdf

- p54 http://www.lamas.org.uk/images/documents/Transactions59/039-060%20Crown%20Wharf.pdf

- "The Battle of Hackney | the view from the bridge". leabridge.org.uk.

- Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape, Rackham, p50

- Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape, Rackham, p55

- "Hackney: Dalston and Kingsland Road | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk.

- "Cemetery". www.cwgc.org.

- "Brooke House | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk.

- Kimmelman, Michael (1 March 2019). "New York Has a Public Housing Problem. Does London Have an Answer?" – via NYTimes.com.

- "Hackney: Introduction | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk.

- Clapton Common 30 June 2009 (Planning Inspectorate Casework) accessed 19 Sept 2009

- Brown, Joe (2009). London Railway Atlas. Hersham: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-3397-9.

- Forgotten Stations of Greater London by J.E.Connor and B.Halford

- Chronology of London Railways by H.V.Borley

- Vyas, Shekha. "New bridge to cut commute between Hackney Downs and Central". Hackney Gazette.

- Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Yeovil: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 111. ISBN 1-85260-508-1. R508.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Body, p.109

- "A Very Political Railway" De Burton, Alan; Electric Railway Society 4 March 2015; Retrieved 23 May 2016

- "DLR Horizons Report - a Freedom of Information request to Transport for London". WhatDoTheyKnow. 23 September 2009.

- "Buses from Hackney Central" (PDF).

- Matters, Transport for London | Every Journey. "Permanent bus changes". Transport for London. Retrieved 1 August 2018.