Eugenol

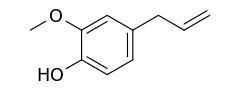

Eugenol /ˈjuːdʒɪnɒl/ is an allyl chain-substituted guaiacol, a member of the allylbenzene class of chemical compounds.[2] It is a colorless to pale yellow, aromatic oily liquid extracted from certain essential oils especially from clove oil, nutmeg, cinnamon, basil and bay leaf.[3][4][5][6] It is present in concentrations of 80–90% in clove bud oil and at 82–88% in clove leaf oil.[7] Eugenol has a pleasant, spicy, clove-like scent.[8] The name is derived from Eugenia caryophyllata, the former Linnean nomenclature term for cloves. (The currently accepted name is Syzygium aromaticum.[9])

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Methoxy-4-(prop-2-en-1-yl)phenol | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.355 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H12O2 | |

| Molar mass | 164.204 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.06 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −7.5 °C (18.5 °F; 265.6 K) |

| Boiling point | 254 °C (489 °F; 527 K) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.19 at 25 °C |

| −1.021×10−4 cm3/mol | |

| Viscosity |

|

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 104 °C (219 °F; 377 K) |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

2-Phenethyl propionate |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Modern uses

Eugenol is used in perfumes, flavorings, and essential oils. It is also used as a local antiseptic and anaesthetic.[10][11] Eugenol can be combined with zinc oxide to form zinc oxide eugenol which has restorative and prosthodontic applications in dentistry. For persons with a dry socket as a complication of tooth extraction, packing the dry socket with a eugenol-zinc oxide paste on iodoform gauze is effective for reducing acute pain.[12] Eugenol-zinc oxide paste is also used for root canal sealing.[13]

It is one of many compounds that is attractive to males of various species of orchid bees, which apparently gather the chemical to synthesize pheromones; it is commonly used as bait to attract and collect these bees for study.[14] It also attracts female cucumber beetles.[15] It was recently discovered that eugenol and isoeugenol, floral volatile scent compounds, are catalyzed by a single type of enzyme in the genus Gymnadenia and the gene encoding for this enzyme is the first functionally characterized gene in these species so far.[16]

Clove oil is growing in popularity as an anaesthetic for use on aquarium fish as well as on wild fish when sampled for research and management purposes.[17][18] Where readily available, it presents a humane method to euthanise sick and diseased fish either by direct overdose or to induce sleep before an overdose of eugenol.[19]

Biosynthesis

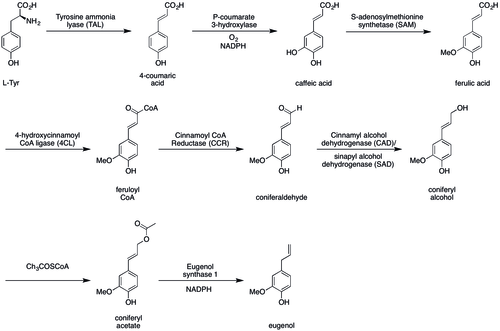

The biosynthesis of eugenol begins with the amino acid tyrosine. L-tyrosine is converted to p-coumaric acid by the enzyme tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL).[20] From here, p-coumaric acid is converted to caffeic acid by p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase using oxygen and NADPH. S-Adenosyl methionine (SAM) is then used to methylate caffeic acid, forming ferulic acid, which is in turn converted to feruloyl-CoA by the enzyme 4-hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA ligase (4CL).[21] Next, feruloyl-CoA is reduced to coniferaldehyde by cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR). Coniferaldeyhyde is then further reduced to coniferyl alcohol by cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) or sinapyl-alcohol dehydrogenase (SAD). Coniferyl alcohol is then converted to an ester in the presence of the substrate CH3COSCoA, forming coniferyl acetate. Finally, coniferyl acetate is converted to eugenol via the enzyme eugenol synthase 1 and the use of NADPH.

Bioactivity and toxicity

Eugenol and thymol were found to possess general anesthetic properties. Like many other anesthetic agents, these 2-alkyl(oxy)phenols were found to act as positive allosteric modulators of the GABAA receptor. Although these eugenol and thymol are too toxic and not potent enough to use clinically, these findings led to the development of 2-substituted phenol anesthetic drugs, including propanidid (later withdrawn) and the widely used propofol.[22]

Eugenol is hepatotoxic, meaning it may cause damage to the liver.[23][24] Overdose is possible, causing a wide range of symptoms from blood in the patient's urine, to convulsions, diarrhoea, nausea, unconsciousness, dizziness, or rapid heartbeat.[25] According to a published 1993 report, a 2-year-old boy nearly died after taking between 5 and 10 ml.[26]

Allergy

Eugenol is subject to restrictions on its use in perfumery[27] as some people may become sensitised to it, however, the degree to which eugenol can cause an allergic reaction in humans is disputed.[28]

Eugenol is a component of balsam of Peru, to which some people are allergic.[29][30] When eugenol is used in dental preparations such as surgical pastes, dental packing, and dental cement, it may cause contact stomatitis and allergic cheilitis.[29] The allergy can be discovered via a patch test.[29]

Natural occurrence

Eugenol naturally occurs in several plants, including the following:

- Cloves (Syzygium aromaticum)[31][32][33]

- Wormwood

- Cinnamon[32][34]

- Cinnamomum tamala[35]

- Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans)[36]

- Ocimum basilicum (sweet basil)[37]

- Ocimum gratissimum (African basil)[16][38]

- Ocimum tenuiflorum (syn. Ocimum sanctum, tulsi or holy basil)

- Japanese star anise[39]

- Lemon balm[40]

- Dill

- Pimenta racemosa

- Vanilla

- Bay laurel

- Celery

- Ginger

- Wood avens

References

- Bingham EC, Spooner LW (1932). "The Fluidity Method for the Determination of Association. I". Journal of Rheology. 3 (2): 221–244. Bibcode:1932JRheo...3..221B. doi:10.1122/1.2116455. ISSN 0097-0360.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database; CID=3314, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/3314 (accessed 26 Feb. 2019).

- "Constituents of the essential oil from leaves and buds of clove (Syzigium caryophyllatum L.) Alston" (PDF). Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research BCSIR Laboratories. 4: 451–454.

- Mallavarapu GR, Ramesh S, Chandrasekhara RS, Rajeswara Rao BR, Kaul PN, Bhattacharya AK (1995). "Investigation of the essential oil of cinnamon leaf grown at Bangalore and Hyderabad". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 10 (4): 239–242. doi:10.1002/ffj.2730100403.

- Yield and Oil Composition of 38 Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Accessions Grown in Mississippi Archived 15 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Typical G.C. for bay leaf oil". Thegoodscentscompany.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- Barnes J, Anderson LA, Phillipson JS (2007) [1996]. Herbal Medicines (PDF) (3rd ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-623-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Human Metabolome Database: Showing metabocard for Eugenol (HMDB0005809)". www.hmdb.ca. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Cortés-Rojas DF, de Souza CR, Oliveira WP (February 2014). "Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 4 (2): 90–6. doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(14)60215-X. PMC 3819475. PMID 25182278.

- Sell AB, Carlini EA (1976). "Anesthetic action of methyleugenol and other eugenol derivatives". Pharmacology. 14 (4): 367–77. doi:10.1159/000136617. PMID 935250.

- Jadhav BK, Khandelwal KR, Ketkar AR, Pisal SS (February 2004). "Formulation and evaluation of mucoadhesive tablets containing eugenol for the treatment of periodontal diseases". Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 30 (2): 195–203. doi:10.1081/DDC-120028715. PMID 15089054.

- Tarakji B, Saleh LA, Umair A, Azzeghaiby SN, Hanouneh S (April 2015). "Systemic review of dry socket: aetiology, treatment, and prevention". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 9 (4): ZE10-3. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2015/12422.5840. PMC 4437177. PMID 26023661.

- Ferracane, Jack L. (2001). Materials in Dentistry: Principles and Applications (2nd ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-2733-4.

- Schiestl FP, Roubik DW (January 2003). "Odor compound detection in male euglossine bees". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 29 (1): 253–7. doi:10.1023/A:1021932131526. PMID 12647866.

- "Cucumber Beetles: Organic and Biorational Integrated Pest Management (Summary)". Attra.ncat.org. 5 August 2013. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- Gupta AK, Schauvinhold I, Pichersky E, Schiestl FP (December 2014). "Eugenol synthase genes in floral scent variation in Gymnadenia species" (PDF). Functional & Integrative Genomics. 14 (4): 779–88. doi:10.1007/s10142-014-0397-9. PMID 25239559.

- Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Surgery in Pet Fish. Atlantic Coast Veterinary Conference. 2001. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- Grush J, Noakes DL, Moccia RD (February 2004). "The efficacy of clove oil as an anesthetic for the zebrafish, Danio rerio (Hamilton)". Zebrafish. 1 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1089/154585404774101671. PMID 18248205.

- Monks, Neale (2 April 2009). "Aquarium Fish Euthanasia" (PDF). Fish Channel. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Dewick, P. M. (2009). Medicinal Natural Products. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470742761. ISBN 9780470742761.

- Harakava, R. (2005). "Genes encoding enzymes of the lignin biosynthesis pathway in Eucalyptus". Genet. Mol. Biol. 28 (3 suppl): 601–607. doi:10.1590/S1415-47572005000400015.

- Tsuchiya H (August 2017). "Anesthetic Agents of Plant Origin: A Review of Phytochemicals with Anesthetic Activity". Molecules. 22 (8): 1369. doi:10.3390/molecules22081369. PMC 6152143. PMID 28820497.

- Thompson DC, Barhoumi R, Burghardt RC (March 1998). "Comparative toxicity of eugenol and its quinone methide metabolite in cultured liver cells using kinetic fluorescence bioassays". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 149 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1006/taap.1997.8348. PMID 9512727.

- Fujisawa S, Atsumi T, Kadoma Y, Sakagami H (August 2002). "Antioxidant and prooxidant action of eugenol-related compounds and their cytotoxicity". Toxicology. 177 (1): 39–54. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00194-4. PMID 12126794.

- "Eugenol Oil Overdose". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- Hartnoll G, Moore D, Douek D (September 1993). "Near fatal ingestion of oil of cloves". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 69 (3): 392–3. doi:10.1136/adc.69.3.392. PMC 1029532. PMID 8215554.

- "IFRA". www.ifraorg.org. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011.

- "Cropwatch Claims Victory Regarding "26 Allergens" Legislation" (PDF). leffingwell.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- Schmalz G, Bindslev DA (2008). Biocompatibility of Dental Materials. p. 352. ISBN 978-3-540-77782-3.

- Bruynzeel, Derk P. (2014). "Balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae)". Management of Positive Patch Test Reactions. Springer. pp. 53–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55706-4_11. ISBN 978-3-540-44347-6.

- Pathak SB, Niranjan K, Padh H, Rajani M (2004). "TLC Densitometric Method for the Quantification of Eugenol and Gallic Acid in Clove". Chromatographia. 60 (3–4): 241–244. doi:10.1365/s10337-004-0373-y. S2CID 95396304.

- Bullerman LB, Lieu FY, Seier SA (July 1977). "Inhibition of growth and aflatoxin production by cinnamon and clove oils. Cinnamic aldehyde and eugenol". Journal of Food Science. 42 (4): 1107–1109. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1977.tb12677.x.

- Lee K, Shibamoto T (2001). "Antioxidant property of aroma extract isolated from clove buds [Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. et Perry]". Food Chemistry. 74 (4): 443–448. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00161-3.

- Kreydiyyeh SI, Usta J, Copti R (September 2000). "Effect of cinnamon, clove and some of their constituents on the Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase activity and alanine absorption in the rat jejunum". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 38 (9): 755–62. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(00)00073-9. PMID 10930696.

- Dighe VV, Gursale AA, Sane RT, Menon S, Patel PH (2005). "Quantitative Determination of Eugenol from Cinnamomum tamala Nees and Eberm. Leaf Powder and Polyherbal Formulation Using Reverse Phase Liquid Chromatography". Chromatographia. 61 (9–10): 443–446. doi:10.1365/s10337-005-0527-6. S2CID 97399632.

- Bennett A, Stamford IF, Tavares IA, Jacobs S, Capasso F, Mascolo N, et al. (1988). "The biological activity of eugenol, a major constituent of nutmeg (..Myristica fragrans..): Studies on prostaglandins, the intestine and other tissues". Phytotherapy Research. 2 (3): 124–130. doi:10.1002/ptr.2650020305.

- Johnson CB, Kirby J, Naxakis G, Pearson S (1999). "Substantial UV-B-mediated induction of essential oils in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.)". Phytochemistry. 51 (4): 507–510. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00767-5.

- Nakamura CV, Ueda-Nakamura T, Bando E, Melo AF, Cortez DA, Dias Filho BP (September 1999). "Antibacterial activity of Ocimum gratissimum L. essential oil" (PDF). Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 94 (5): 675–8. doi:10.1590/S0074-02761999000500022. PMID 10464416. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- Ize-Ludlow D, Ragone S, Bruck IS, Bernstein JN, Duchowny M, Peña BM (November 2004). "Neurotoxicities in infants seen with the consumption of star anise tea". Pediatrics. 114 (5): e653-6. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0058. PMID 15492355.

- "Lemon balm". University of Maryland Medical Center. Retrieved 7 December 2010.