CS gas

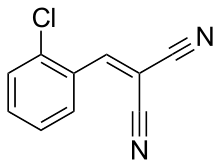

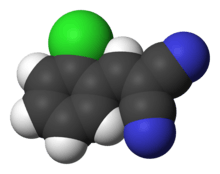

The compound 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile (also called o-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile; chemical formula: C10H5ClN2), a cyanocarbon, is the defining component of tear gas commonly referred to as CS gas, which is used as a riot control agent. Exposure causes a burning sensation and tearing of the eyes to the extent that the subject cannot keep their eyes open, and a burning irritation of the mucous membranes of the nose, mouth and throat, resulting in profuse coughing, nasal mucus discharge, disorientation, and difficulty breathing, partially incapacitating the subject. CS gas is an aerosol of a volatile solvent (a substance that dissolves other active substances and that easily evaporates) and 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile, which is a solid compound at room temperature. CS gas is generally accepted as being non-lethal. It was first synthesized by two Americans, Ben Corson and Roger Stoughton,[6] at Middlebury College in 1928, and the chemical's name is derived from the first letters of the scientists' surnames.[7][8]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

[(2-Chlorophenyl)methylidene]propanedinitrile | |

| Other names

2-(2-Chlorobenzylidene)malononitrile 2-Chlorobenzalmalononitrile o-Chlorobenzylidene malononitrile OCBM Tear gas | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.018.435 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2810, 3276, 2811 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H5ClN2[1] | |

| Molar mass | 188.6 g/mol[2] |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder Colourless gas when burned |

| Odor | Pepper-like[3] |

| Density | 1.04 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 93 °C (199 °F; 366 K) |

| Boiling point | 310 °C (590 °F; 583 K)[4] |

| Insoluble | |

| Vapor pressure | 3.4×10−5 mmHg at 20 °C |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | See: data page |

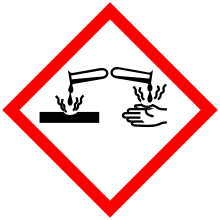

| GHS pictograms |      |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements |

H302, H314, H318, H330, H335, H372, H400, H410 |

| P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P273, P280, P284, P301+312, P301+330+331, P303+361+353, P304+340, P305+351+338, P310, P312, P314, P320, P321, P330, P363, P391, P403+233, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LCLo (lowest published) |

|

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 0.05 ppm (0.4 mg/m3)[3] |

REL (Recommended) |

C 0.05 ppm (0.4 mg/m3) [skin][3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

2 mg/m3[3] |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

SDBS

5-chloro-2-quinolinecarbonitrile |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

CS was developed and tested secretly at Porton Down in Wiltshire, UK, in the 1950s and 1960s. CS was used first on animals, then subsequently on British Army servicemen volunteers. CS has less effect on animals due to "under-developed tear-ducts and protection by fur".[9]

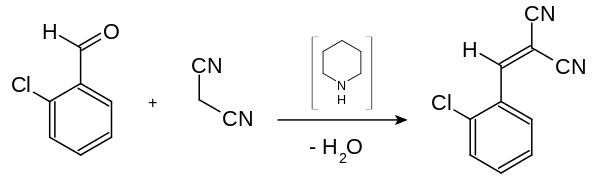

Production

CS is synthesized by the reaction of 2-chlorobenzaldehyde and malononitrile via the Knoevenagel condensation:

- ClC6H4CHO + H2C(CN)2 → ClC6H4CHC(CN)2 + H2O

The reaction is catalysed with weak base like piperidine or pyridine. The production method has not changed since the substance was discovered by Corson and Stoughton.[10] Other bases, solvent free methods and microwave promotion have been suggested to improve the production of the substance.[11]

The physiological properties had been discovered already by the chemists first synthesising the compound in 1928: "Physiological Properties. Certain of these dinitriles have the effect of sneeze and tear gases. They are harmless when wet but to handle the dry powder is disastrous."[10]

Use as an aerosol

As 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile is a solid at room temperature, not a gas, a variety of techniques have been used to make this solid usable as an aerosol:

- Melted and sprayed in the molten form.

- Dissolved in organic solvent.

- CS2 dry powder (CS2 is a siliconized, micro-pulverized form of CS).

- CS from thermal grenades by generation of hot gases.[2]

In the Waco Siege in the United States, CS was dissolved in the organic solvent dichloromethane (also known as methylene chloride). The solution was dispersed as an aerosol via explosive force and when the highly volatile dichloromethane evaporated, CS crystals precipitated and formed a fine dispersion in the air.[2]

Effects

Many types of tear gas and other riot control agents have been produced with effects ranging from mild tearing of the eyes to immediate vomiting and prostration. CN and CS are the most widely used and known, but around 15 different types of tear gas have been developed worldwide, e.g. adamsite or bromoacetone, CNB, and CNC. CS has become the most popular due to its strong effect. The effect of CS on a person will depend on whether it is packaged as a solution or used as an aerosol. The size of solution droplets and the size of the CS particulates after evaporation are factors determining its effect on the human body.[12]

The chemical reacts with moisture on the skin and in the eyes, causing a burning sensation and the immediate forceful and uncontrollable shutting of the eyes. Effects usually include tears streaming from the eyes, profuse coughing, exceptional nasal discharge that is full of mucus, burning in the eyes, eyelids, nose and throat areas, disorientation, dizziness and restricted breathing. It will also burn the skin where sweaty or sunburned. In highly concentrated doses, it can also induce severe coughing and vomiting. Most of the immediate effects wear off within an hour (such as exceptional nasal discharge and profuse coughing), although respiratory and oral symptoms may persist for months.[13] Excessive exposure can cause chemical burns resulting in permanent scarring.[14] Clothing affected by CS gas will need to be washed several times.

Secondary effects

People or objects contaminated with CS gas can cause secondary exposure to others, including healthcare professionals and police. In addition, repeated exposure may cause sensitisation.[15]

Toxicity

TRPA1 (Transient Receptor Potential-Ankyrin 1) ion channel expressed on nociceptors (especially trigeminal) has been implicated as the site of action for CS gas in rodent models.[16][17]

Although described as a non-lethal weapon for crowd control, studies have raised doubts about this classification. CS can cause severe pulmonary damage and can also significantly damage the heart and liver.[18]

On 28 September 2000, Prof. Dr. Uwe Heinrich released a study commissioned by John C. Danforth, of the United States Office of Special Counsel, to investigate the use of CS by the FBI at the Branch Davidians' Mount Carmel compound. He said no human deaths had been reported, but concluded that the lethality of CS used would have been determined mainly by two factors: whether gas masks were used and whether the occupants were trapped in a room. He suggests that if no gas masks were used and the occupants were trapped, then, "there is a distinct possibility that this kind of CS exposure can significantly contribute to or even cause lethal effects".[2]

CS gas can have a clastogenic effect (abnormal chromosome change) on mammalian cells, but no studies have linked it to miscarriages or stillbirths.[18] In Egypt, CS gas was reported to be the cause of death of several protesters in Mohamed Mahmoud Street near Tahrir square during the November 2011 protests. The solvent in which CS is dissolved, methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK), is classified as harmful by inhalation; irritating to the eyes and respiratory system; and repeated exposure may cause skin dryness or cracking.[19]

Use

CS is used in spray form by many police forces as a temporary incapacitant and to subdue attackers, persons, or civil protestors. Officers who are trained in the use and application of CS spray are routinely exposed to it as part of their training.

Blank pistol cartridges carrying CS in powder form have been released to the public. These, when fired at relatively close ranges, fully expose the target to the effects of CS, and are employed as a potent defensive weapon in regions where blank firing pistols are legally permitted for such use.

Although predominantly used by police it has also been used in criminal attacks in various countries.[20][21][22][23]

Use of CS in war is prohibited under the terms of the Chemical Weapons Convention, signed by most nations in 1993 with all but five other nations signing between 1994 and 1997. The reasoning behind the prohibition is pragmatic: use of CS by one combatant could easily trigger retaliation with much more toxic chemical weapons such as nerve agents. Only four nations have not signed the Chemical Weapons Convention and are therefore unhindered by restrictions on the use of CS gas: Angola, Egypt, North Korea and Somalia.[24]

Domestic police use of CS is legal in many countries, as the Chemical Weapons Convention prohibits only military use.

Bahrain

.jpg)

CS gas was used extensively by Bahrain's police from the start of the Bahraini uprising.[25](p260) The Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry concluded that Bahrain's police used a disproportionate amount of CS gas when dispersing protests, and that in some situations, police fired CS gas into private homes in an "unnecessary and indiscriminate" manner.[25](p277) In one particular incident witnessed by Commission investigators, police fired "at least four tear gas canisters (each containing six projectiles) ... from a short range into the kitchen and living room of a home."[25](p261)

According to opposition activists and families of the dead, ten individuals died as a result of CS gas between 25 March 2011 and 17 December 2011.[26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35] One allegedly died from the impact of the CS gas canister,[31] and the remainder are said to have died from the effects of inhaling the gas. The Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry received information that a further three deaths may have been attributable to the use of CS gas.[25](pp239–40,253) Of these three, one allegedly died from the impact of the canister, and two from the effects of inhaling the gas.

Canada

The Canadian Forces exposes basic training candidates to CS gas as part of gas mask training and drills. This training continues in subsequent career stages. Many law enforcement agencies also use CS gas as a riot control device. Since 2008, the SPVM police force in Montreal has increased its use of CS Gas for crowd control, although Police policy is to only use it as a last resort. Several incidents where protesters have been seriously injured by having CS gas fired at them from point-blank range have raised concerns about the methodology and training of Officers in the Montreal Riot Squad, particularly in relation to "Use of Force".[36]

Chile

Tear gas is routinely used in Chile by Carabineros, to disrupt civilian protests.[37] During the 2019 uprising the use of expired gas has been reported, prompting Carabineros to say that "they are like yogurt expired 5 days ago, it doesn’t damage people".[38]

Cyprus

CS was first tested in the field by the British army in Cyprus in 1958. At this time it was known by the code name T792.[39]

Egypt

CS has been widely used by Egyptian Police/Military Forces from January 2011 onwards.

Hong Kong

The Police Tactical Unit of the Hong Kong Police Force used 87 rounds of CS projectiles (both riot gun launched and hand thrown) in Hong Kong on 28 September 2014 against thousands of protesters obstructing major thoroughfares in Hong Kong 2014 Hong Kong protests, also known as the Umbrella Movement.

The CS gas canisters and content used were purchased by the Hong Kong SAR Government from CHEMRING, a British weapons manufacturer. The crowd used umbrellas to fend off the gas, which was often ineffective. Apart from the HK police, CS gas spray is also used by Witness Protection and Firearms Section of Independent Commission Against Corruption (Hong Kong).

From 12 June to 4 August 2019, police used 1000 tear gas canisters. Then, on the single day of 5 August, police fired more than 800 tear gas canisters in their operations throughout almost every district of the city.[40] In one instance, a tear gas canister was deployed indoors, in Kwai Fong Station during a march, on 11 August 2019. The police initially denied the incident.[41] In defense, protestors are seen picking up tear gas cans with thick gloves to throw them back or to extinguish them in sealed water containers.[42]

Up to 22 October 2019, over 5000 made-in-China tear gas canisters have been deployed by the Hong Kong Police Force. Canisters marked with dates overdue have been collected in many occasions. It is unpredictable for the potential hazards to the Hong Kong environment and living conditions. Recent massive deaths of fish around Hong Kong seas was also suspected to be one of the consequences. Many birds were found dead in the Chinese University of Hong Kong, after 12 November that the riot police fired over 2000 tear gases towards the campus.[43] A Hong Kong journalist, Chan Yu-hong from the Stand News declared he was diagnosed with chloracne (by Traditional Chinese physician instead of physician[44]) after exposure to made-in-China tear gas while covering the 2019 Hong Kong Protests.

The overuse of tear gas has been one of the concerns in the anti-extradition bill protests.

Iraq

Iraq successfully developed CS during the 1970s and during the 1980s produced tons of the substance firstly at Salman Pak and later at al-Muthanna.[45]

Blackwater Worldwide, acting as an agent of the United States, deployed CS in the Iraq War from a helicopter hovering over a checkpoint in the Green Zone in Baghdad.[46]

Israel

Israel Police forces spray CS gas in riot control situations. It is widely used at demonstrations within the Palestinian Territories and at the Israeli West Bank barrier.[47][48]

Philippines

CS tear gas was used in suppression of the mutiny in Makati that was led by Sen. Antonio Trillanes. The tear gas was fired in the building and all the people in the building including reporters were affected.

Romania

The Gendarmerie of Bucharest used large quantities of CS gas against civilians during the protests of 10 August 2018 in Bucharest.[49]

Spain

Tear gas is not commonly used in Spain but it has been used some times to disrupt civilian protests by the Policia Nacional and Mossos d'Esquadra in Catalonia.[50]

Sri Lanka

The LTTE, also known as Tamil Tigers of Sri Lanka, an insurgent group in Sri Lanka used CS gas against government forces in September 2008.[51] Its use hindered the army's progress but ultimately proved ineffective in preventing the army from overrunning LTTE positions.

This is one of the few cases of insurgents using CS gas.

Sudan

The Sudanese forces extensively used CS gas during the latest wave of demonstrations began in 2018.[52] The use of the CS gas of gunshots type or hand grenade is not exclusive for police forces. It is widely used by non-trained militia to suppress protesters movement.[53] CS gas shots is generally used as a shooting weapon aimed of the faces of protesters and cause serious injury and probably permanent eyes damage.[54] Some cases were recorded of death of chocking on tear gas [55] bombed in closed or semi-closed areas.

United Kingdom

Northern Ireland

CS gas was used extensively in the Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland during the "Battle of the Bogside", a two-day riot in August 1969. A total of 1,091 canisters containing 12.5g of CS each, and 14 canisters containing 50 g of CS each, were released in the densely populated residential area.[56] On 30 August the Himsworth Inquiry was set up to investigate the medical effects of its use in Derry. Its conclusions, viewed in the political context of the time, still pointed towards the necessity of further testing of CS gas before being used as a riot control agent. During the rioting in Belfast, the following year, known as the Falls Curfew, the Army fired up to 1,600 canisters into the densely populated Falls Road area. It was also used in Lenadoon on 9 July 1972 on the breakdown of the IRA ceasefire. Not long after, the British Army and RUC ceased using CS in Northern Ireland.

Great Britain

CS gas

CS gas has not been routinely deployed on the British mainland. It has seen use in rare cases.[57] The first use of CS gas on the UK mainland that was not part of military training was carried out in 1944 during a hostage siege at a north London address. Soldiers were asked to throw CS grenades through the skylight in hope of bringing the incident to a speedy conclusion, but the hostage-taker had brought his civilian-issue gas mask with him, negating the effect. The siege of Trough Gate 1973 in Oldham was the second non-military use of CS gas on the UK mainland. During a four-hour standoff, Frank Alan Stockton shot at police but was flushed from his home with CS gas and police dogs.[58][59][60]

During the 1980 assault on the Iranian Embassy, SAS soldiers used CS gas contained within stun grenades to incapacitate the militants who had kept the building under siege for six days. All the remaining hostages were saved and all but one of the hostage-takers were killed, with the other being taken into custody.[61] In 1981, CS gas was used to quell rioting in the Toxteth area of Liverpool.[62][63]

Following the 2011 England riots, there was consideration given to making CS gas, water cannon and other riot control measures available to police for use in the event of serious disorder.[64] The British Armed Forces use CS gas annually to test their chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defense (CBRN) equipment. During initial training they introduce recruits to CS gas by placing them in a small enclosed space known as a Confidence Test Facility (CTF) and igniting chemical tablets to induce CS production. After recruits have carried out their CBRN drills, they must remove their respirators so that they are exposed to the CS for up to 20 seconds to experience its effects and become confident their respirators work.[65]

CS spray

CS incapacitant spray has been used routinely by the British police since its introduction in 1996. It is issued as an item of equipment to police officers for protection and to assist in dealing with violent incidents.[57][66] A six-month trial by sixteen police forces in England began on 1 March 1996. CS spray was used in the UK more than 10,000 times in the period between its introduction in 1996 and September 1998.[67] Some forces have opted to replace CS spray with Captor or PAVA spray,[68][69] with 60% of forces now estimated to be using PAVA.[70]

The CS spray used by police forces is in the form of a hand-held aerosol canister containing a 5% solution of CS dissolved in methyl isobutyl ketone and propelled by pressurized nitrogen.[71] The CS spray used by UK police is generally more concentrated than that used by American police forces (5% vs 1%).[72] The liquid stream is directed where the user points the canister, being accurate up to 4 metres. Police are also trained in helping the incapacitated person recover once successfully restrained.[71] Under UK firearm law, CS and other incapacitant sprays are classed as prohibited weapons, making it unlawful for a member of the public to possess them.[73]

On 16 March 1996, a Gambian asylum seeker, Ibrahima Sey, was taken to Ilford Police Station in east London. Whilst incapacitating Sey, who was suffering from excited delirium, police sprayed him with CS spray and held him on the ground for approximately 15 minutes, and he subsequently died.[74] In 1999, the mental health charity MIND called for a suspension of the use of CS spray on mentally ill people until it was proved to be safe.[75] In February 2006, Dan Ford, from Wareham in Dorset, received permanent scarring to his face after being sprayed with CS during an arrest by police. Ford was subsequently advised by doctors to stay out of sunlight for at least 12 months. After the incident, his cousin, Donna Lewis, was quoted as saying, "To look at him, it was like looking at a melting man, with liquid oozing from his face."[76]

United States

CS is used by many police forces within the United States. It was used by Federal Bureau of Investigation law enforcement officials in the 1993 Waco Siege.[77] Riot police in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in September 2009 used CS gas and riot control techniques to disperse assemblies in the vicinity of the 2009 G-20 Pittsburgh summit.

In Berkeley, California during the Bloody Thursday events in the People's Park on 21 May 1969, a midday memorial was held for student James Rector, a non-protester shot and killed by police, at Sproul Plaza on the University campus. In his honor, several thousand people peacefully assembled to listen to speakers remembering his life. National Guard troops surrounded Sproul Plaza, donned their gas masks, and pointed their bayonets inward, while helicopters dropped CS gas directly on the trapped crowd. No escape was possible, and the gas caused acute respiratory distress, disorientation, temporary blindness and vomiting. Many people, including children and the elderly, were injured during the ensuing panic. The gas was so intense that breezes carried it into Cowell Memorial Hospital, endangering patients, interrupting operations and incapacitating nurses. Students at nearby Jefferson and Franklin elementary schools were also affected.[78][79]

Members of the United States armed forces are exposed to CS during initial training, and during training refresher courses or equipment maintenance exercises, using CS tablets that are melted on a hotplate. This is to demonstrate the importance of properly wearing a gas or protective mask, as the agent's presence quickly reveals an improper fit or seal of the mask's rubber gaskets against the face. Following exposure while wearing a mask, recruits are ordered to remove the masks and endure exposure in the room. These exercises also encourage confidence in the ability of the equipment to protect the wearer from such chemical attacks. Such an event is a requirement for graduation from United States Army Basic Training, Air Force Basic Military Training, Navy Basic Training, and Marine Corps recruit training.[80] CS gas in the form of grenades is also used extensively in the United States Marine Corps and United States Army in some service schools. CS gas is used during the final field exercise of the Scout Sniper Basic Course to simulate being compromised. In addition, it is used during the 25 km (16 mi) escape-and-evasion exercise ("Trail of Tears"), the last event before graduation from the course. Navy Corpsmen participating in Field Medic training in order to serve with the Marines must go through their second CS gas exercise before finally arriving at their unit. It is also used during several events in the Marine Corps Basic Reconnaissance Course (BRC) including some rucksack runs and escape-and-evasion exercises. While students going through the course are given the opportunity to bring and wear a gas mask for the event, usually none are worn because once donned, gas masks could not be removed until the end of the exercise. This could last anywhere from 3–12 hours and would make running 25 km while wearing 125 lb (57 kg) of gear virtually impossible.

Vietnam

It has been reported that thousands of tons of CS gas were used by the U.S. forces in Vietnam to bring Viet Cong into the open. It was also used by the North Vietnamese forces in some battles like Hue in 1968 or during the Easter Offensive in 1972.[81]

Elsewhere

CS gas has been and is still routinely used by Greek riot police (MAT) in order to quell student and labour protests, as well as riots.

CS was used to quell a protest in Lusaka, Zambia in July 1997 and the 1999 WTO riots in Seattle. Amnesty International reported that it had been manufactured by the UK company Pains-Wessex. Subsequently, Amnesty called for an export ban when the receiving regime is either not fully trained in the use of CS, or had shown usage "contrary to the manufacturer’s instructions".[82]

In September 2000, the Guardian newspaper revealed how a UK company, HPP, used legal loopholes to export CS to a private security company in Rwanda, in breach of United Nations sanctions.[83] The Guardian also reported that CS was used by the Hutu militia in Rwanda to flush Tutsis out of buildings before hacking them to death.

CS has been used by the government in South Africa; by Israel against Palestinians and Israelis; by the South Korean government in Seoul, and during the Balkan conflicts by Serbia. In Malta it was used by police between 1981 and 1987 to the detriment of Nationalist Party Supporters.

CS tear gas was used at the G8 protests in Genoa, Italy[84] and Quebec City, Canada[85] during the FTAA anti-globalization demonstrations during the Quebec City Summit of the Americas.

The Malaysia Federal Reserve Unit has also been known to use CS tear gas against its citizens who rallied for clean and fair elections under what were called Bersih rallies in 2011[86] and 2012.[87]

The Canadian, Norwegian and Australian Defence Forces train their personnel with CS gas in a manner similar to that of the USA, as it is a basic part of CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear) training. Gas is released by burning tablets, usually in a building reserved for this purpose (a "gas hut"). In the training, the person enters the building unprotected, and must fit and clear the gas mask before leaving. Other drills such as drinking and under-mask decontamination are also practised. Some Norwegian units are exposed to CS gas while engaged in mental and physical activity such as addressing the officer in command by stating name, rank and troop before doing 30 push-ups.[88]

In Australia, prison officers used CS gas against five teenage boys in Darwin's Don Dale Juvenile Detention Centre in August 2014.[89]

See also

References

- Williams KE. "Detailed Facts About Tear Agent O-Chlorobenzylidene Malononitrile (CS)]" (PDF). U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007.

- Heinrich U (September 2000). "Possible lethal effects of CS tear gas on Branch Davidians during the FBI raid on the Mount Carmel compound near Waco, Texas" (PDF). Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0122". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Hoenig, Steven L. (2006). Compendium of Chemical Warfare Agents. Springer. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-387-34626-7.

- "o-Chlorobenzylidene malononitrile". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Corson BB, Stoughton RW (1928). "Reactions of Alpha, Beta-Unsaturated Dinitriles". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 50 (10): 2825–2837. doi:10.1021/ja01397a037.

- "CS". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "CS, chemical compound". columbia.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved on 23 September 2007.

- "Orthochlorobenzylidenemalononitrile ClC6H4CHCCN(CN)2 Archived 28 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine". Zarc International. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- Corson BB, Stoughton RW (1928). "Reactions of Alpha, Betha-Unsaturated Dinitriles". J Am Chem Soc. 50 (10): 2825–2837. doi:10.1021/ja01397a037.

- Pande A, Ganesan K, Jain AK, Gupta PK, Malhotr RC (2005). "Novel Eco-Friendly Process for the Synthesis of 2-Chlorobenzylidenemalononitrile and ITS Analogues Using Water As a Solvent". Org Proc Res Develop. 9 (2): 133–136. doi:10.1021/op0498262.

- "Safer Restraint: A report of the conference held in April 2002 at Church House, Westminster." Police Complaints Authority. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- Karagama YG, Newton JR, Newbegin CJ (April 2003). "Short-term and long-term physical effects of exposure to CS spray". JRSM. 96(4): 172–174. doi:10.1258/jrsm.96.4.172. PMC 539444. PMID 12668703.

- "CS spray man 'scarred for life'". BBC News. 2 February 2006. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- Carron PN, Yersin B (June 2009). "Management of the effects of exposure to tear gas". BMJ. 338: b2283. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2283. PMID 19542106.

- Bessac BF, Sivula M, von Hehn CA, Caceres AI, Escalera J, Jordt SE (April 2009). "Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 antagonists block the noxious effects of toxic industrial isocyanates and tear gases". FASEB Journal. 23 (4): 1102–14. doi:10.1096/fj.08-117812. PMC 2660642. PMID 19036859.

- Brône B, Peeters PJ, Marrannes R, Mercken M, Nuydens R, Meert T, Gijsen HJ (September 2008). "Tear gasses CN, CR, and CS are potent activators of the human TRPA1 receptor". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 231 (2): 150–6. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.005. PMID 18501939.

- Hu, Howard (4 August 1989). "Tear Gas—Harassing Agent or Toxic Chemical Weapon?". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 262 (5): 660–3. doi:10.1001/jama.1989.03430050076030. PMID 2501523.

- "MSDS for 99% 4-Methyl-2-pentanone (MIBK)" (PDF). Alfa Aesar. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Kelso, Paul. "CS gas attack by former pupil injures 68 children." The Guardian. 1 October 1999. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- Condon, Deborah. "Gas attack at Dublin hospital." www.irishhealth.com. 14 May 2004. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- "Shopkeeper attacked with CS gas." BBC News. 1 December 2005. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- "Car thieves spray gas at motorist." BBC News. 4 January 2006. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. "States that nave neither signed nor acceded to the Chemical Weapons Convention". Retrieved 17. August 2014

- Report of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (PDF) (Report). Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry. 23 November 2011.

- وفاة سبعيني في المعامير اختناقاً بغازات "الأمن" و "الداخلية" تنفي [Death of septuagenarian in Ma'ameer by suffocation from gas, Public Security and Ministry of Interior deny]. Alwasat (in Arabic). 26 March 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Bahrain group calls for boycott of Iranian goods". Associated Press. 30 April 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Bahrain police 'suppress protest'". Al Jazeera. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Woman's death sparks new tension in Bahrain". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 16 July 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Bahrain probes abuse after tear gas kills man". Reuters. 31 August 2011. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Goodman JD (2 August 2011). "A 14-Year-Old Boy Is Killed in Bahrain as Security Forces Break Up a Protest". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Bahrain man dies after inhaling tear gas". Associated Press. 15 September 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "عائلة لطف الله: وثقنا وفاة والدنا متأثراً ب "مسيلات الدموع [Family of Lutf Allah: we believe that our father's death was caused by tear gas]. Alwasat (in Arabic). 1 October 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Kerr S (12 December 2011). "Baby's death threatens Bahrain reform agenda". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Thousands demonstrate at funeral of Bahrain man". The Guardian. London. Associated Press. 18 December 2011.

- "Police stun grenade blamed for student's eye injury". CBC News. 8 March 2012.

- "Tear gas used at Chile protest over education". aljazeera. 12 June 2014.

- "T13 | Tele 13". www.t13.cl. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Final Report of the Expert Panel to Review SAS Veterans’ Health Concerns (Appendix D) Archived 26 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- Leung Kai-cheong K (20 August 2019). "Why police should limit the use of tear gas". EJ Insight. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Ramzy A, Lai KR (18 August 2019). "1,800 Rounds of Tear Gas: Was the Hong Kong Police Response Appropriate?". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

'Discharging indoors leads to panic, can lead to stampede, and at its worst it can lead to dire health consequences, including death, if people cannot escape the suffocating effects of the gas,' said Michael Power, a civil rights lawyer based in South Africa who specializes in protests and policing.

- "Protesters' expert response to riot police". NewsComAu. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "r/HongKong - Birds died after the release of 25K tear gas in the Chinese University of Hong Kong". reddit. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "氯痤瘡". Stand News (in Chinese). Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "WMD Profiles: Chemical Archived 18 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine." Iraq Watch. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- Risen J (10 January 2008). "2005 Use of Gas by Blackwater Leaves Questions". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- "Four Palestinians faint after inhaling CS gas". 8 August 2009. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- "Dozens hit by CS gas during anti-wall demonstrations". 22 August 2009.

- "Jandarmeria: Gazele lacrimogene folosite la proteste provin exclusiv de la producători autorizaţi şi certificaţi. Substanţele sunt folosite şi de forţe de ordine europene". Mediafax. Bucharest. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "Third night of violence in Barcelona after jailing of Catalan separatists". The Guardian. 16 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- "LTTE used CS Gas to attack Soldiers". Lanka Daily News. 18 September 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- "2 killed amid anti-govt protests in Sudan". 18 January 2019.

- "Sudanese security forces use tear gas to break up women's protest". Reuters. 10 February 2019.

- "Wounded Sudanese 'proud' of injuries sustained during protests".

- "Sudanese fruit seller dies choking on tear gas fired at protesters". 17 February 2019.

- McClean R (1997). The Road To Bloody Sunday (revised edition). Guildhall: Printing Press. ISBN 978-0-946451-37-1.

- "British police face a CS gas attack". Guardian. London. 8 July 1999. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Ayala B (29 July 2009). "Hero of Trough Gate siege dies at 72". Oldham Evening Chronicle.

- McPhee D. "Photo, The siege of Trough Gate Oldham 1973". The Guardian. TopFoto. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- McPhee D. "Photo, The siege of Trough Gate Oldham 1973". The Guardian. TopFoto. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- Knighton A (21 June 2017). "Operation Nimrod: The SAS Assault on the Iranian Embassy". War History Online.

- Kelly S (1 July 2011). "Toxteth's toxic legacy: Liverpool is still feeling the impact of the Toxteth riots". The Independent. London. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "On This Day: 20 May 1965: British police to be issued with tear gas." BBC News. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- "UK police ponder using CS gas against rioters". Reuters. March 2012.

- "MoD confirms army CS gas investigation". Politics.co.uk. 13 May 2006. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Euripidou E, MacLehose R, Fletcher A (September 2004). "An investigation into the short term and medium term health impacts of personal incapacitant sprays. A follow up of patients reported to the National Poisons Information Service (London)". Emergency Medicine Journal. 21 (5): 548–52. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.012773. PMC 1726417. PMID 15333526.

- "Safety fears prompt CS spray review". BBC News. 24 September 1998. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "'Chilli' spray to replace CS gas". BBC News. 27 June 2005. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "'Safer' Pava to replace CS spray". BBC News. 22 January 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "CAPTOR 2 P.A.V.A." Civil Defence Supply Ltd. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Guidance on the Use of Incapacitant Spray (PDF). Association of Chief Police Officers of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. 2009. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2013.

- Southward RD (January 2000). "CS incapacitant spray". Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine. 17 (1): 76–a–76. doi:10.1136/emj.17.1.76-a. PMC 1756282. PMID 10659007.

- "Weapons subject to general prohibition". Firearms Act 1968. UK Government. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "Report on the death of Ibrahima Sey." Inquest. 1997

- "Experts fear unknown CS spray risks." BBC News. 24 September 1999. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- "CS spray man 'scarred for life'." BBC News. 2 February 2006. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- "A Primer on CS Gas." Public Broadcasting Service. 1995. Retrieved on 23 September 2007

- Nation: Occupied Berkeley. TIME (30 May 1969). Retrieved on 2 February 2011.

- The Sixties and Seventies from Berkeley to Woodstock. Fsmitha.com. Retrieved on 2 February 2011.

- TRADOC Regulation 350-6 Archived 30 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine TRADOC 2007. Retrieved on 13 October 2008

- Bryce, Robert (7 July 2000). "Lethal Weapon: FBI's Use of Tear Gas Questioned at Davidian Trial". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- "Stopping the Torture Trade: 3 – Chemical Control" (PDF). Amnesty International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007.

- Burke J, Johnson-Thomas B (10 September 2000). "British firms trade in torture". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Tartarini L (13 April 2003). "Genova Update". italy.indymedia.org. Archived from the original on 8 August 2003. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Di Matteo, Enzo (17 May 2001). "Foggy Over Tear Gas Safety". NOW Magazine. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- "Malaysia cracks down on protesters]". Al Jazeera. 10 July 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- Shukry A (29 April 2012). "Probe violence against press, media groups urge Najib". The Malaysian Insider. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- "Military magazine detailing Norwegian recruit training" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2017.

- "Own Initiative Investigation Report Services Provided by the Department of Correctional Services at the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre" (PDF). August 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to CS gas. |

- Salem H, Gutting B, Kluchinsky T, Boardman C, Tuorinsky S, Hout J (2008). Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare, Chapter 13 Riot Control Agents, US Army Medical Institute, Borden Institute, pp. 441–484 (2008).

- Carron PN, Yersin B (June 2009). "Management of the effects of exposure to tear gas". BMJ. 338 (7710): b2283. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2283. PMID 19542106.

- Hout J, Hook G, LaPuma P, White D (2010). "Identification of compounds formed during low temperature thermal dispersion of encapsulated o-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile (CS riot control agent)" Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, June 2010

- Hout, Joseph; Kluchinsky, Timothy; LaPuma, Peter; White, Duvel (2011). "Evaluation of CS (o-Chlorobenzylidene Malononitrile) Concentrations During U.S. Army Mask Confidence Training", Journal of Environmental Health, October 2011

- Gas Chromatography NIST

- (rehosted) U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine General Facts About Tear Agent O-Chlorobenzylidene Malononitrile (CS) {pdf}

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – o-Chlorobenzylidene malononitrile

- Patten report recommendations 69 and 70 relating to public order equipment A Paper prepared by the Steering Group led by the Northern Ireland Office – April 2001

- Committees on toxicity, mutagenicity and carcinogenicity of chemicals in food, consumer products and the environment statement on 2-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile (CS) and CS spray, September 1999. (pdf)

- Journal of Non-lethal Combatives, January 2003 Noxious Tear-Gas Bomb Mightier in Peace than in War.

- "Crowd Control Technologies: An Assessment Of Crowd Control Technology Options For The European Union" – The Omega Foundation (pdf)

- Health and safety in policing University of Nottingham paper on CS use in the UK.

- BBC 'wiki' site – entry on CS gas

- eMedicine Information on irritants: Cs, Cn, Cnc, Ca, Cr, Cnb, PS