Buddhism in Thailand

Buddhism in Thailand is largely of the Theravada school, which is followed by 95 percent of the population.[3][4][5] Thailand has the third largest Buddhist population in the world, after China and Japan, with approximately 64 million Buddhists. Buddhism in Thailand has also become integrated with folk religion as well as Chinese religions from the large Thai Chinese population.[6][7] Buddhist temples in Thailand are characterized by tall golden stupas, and the Buddhist architecture of Thailand is similar to that in other Southeast Asian countries, particularly Cambodia and Laos, with which Thailand shares cultural and historical heritage.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 64 million (95%) in 2015[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Throughout Thailand | |

| Religions | |

| Languages | |

| Thai and other languages |

| Part of a series on |

| Theravāda Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

Doctrine

|

|

Key Figures |

Buddhism is believed to have come to what is now Thailand as early as 250 BCE, in the time of Indian Emperor Ashoka. Since then, Buddhism has played a significant role in Thai culture and society. Buddhism and the Thai monarchy has often been intertwined, with Thai kings historically seen as the main patrons of Buddhism in Thailand. Although politics and religion were generally separated for most of Thai history, Buddhism's connection to the Thai state would increase in the middle of the 19th century following the reforms of King Mongkut, that would lead to the development of a royally backed sect of Buddhism and increased centralization of the Thai Sangha under the state, with state control over Buddhism increasing further after the 2014 coup d'état.

Thai Buddhism is distinguished for its emphasis on short term ordination for every Thai man and its close interconnection with the Thai state and Thai culture. The two official branches, or Nikayas, of Thai Buddhism are the royally backed Dhammayuttika Nikaya and the larger Maha Nikaya.

Historical background

Early traditions

Some scholars believe that Buddhism must have been flowing into Thailand from India at the time of the Indian emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire and into the first millennium after Christ.[9] During the 5th to 13th centuries, Southeast Asian empires were influenced directly from India and followed Mahayana Buddhism. The Chinese pilgrim Yijing noted in his travels that in these areas, all major sects of Indian Buddhism flourished.[10] Srivijaya to the south and the Khmer Empire to the north competed for influence and their art expressed the rich Mahāyāna pantheon of bodhisattvas. From the 9th to the 13th centuries, the Mahāyāna and Hindu Khmer Empire dominated much of the Southeast Asian peninsula. Under the Khmer Empire, more than 900 temples were built in Cambodia and in neighboring Thailand.

After the decline of Buddhism in India, missions of Sinhalese monks gradually converted the Mon people and the Pyu city-states from Ari Buddhism to Theravāda and over the next two centuries also brought Theravāda Buddhism to the Bamar people, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, where it supplanted previous forms of Buddhism.[11] Theravada Buddhism was made the state religion only with the establishment of the Sukhothai Kingdom in the 13th century.[12]

13th–19th centuries

The details of the history of Buddhism in Thailand from the 13th to the 19th century are obscure, in part because few historical records or religious texts survived the Burmese destruction of Ayutthaya, the capital city of the kingdom, in 1767. Ayutthaya was the center of Thai Tantric Theravada, which included the Yogāvacara tradition, and has survived in only a few temples as well as possibly the contemporary Dhammakaya tradition. The Tantric Buddhist Yogāvacara tradition was a mainstream Buddhist tradition in Cambodia, Laos and Thailand well into the modern era. An inscription from northern Thailand with tantric elements has been dated to the Sukhothai Kingdom of the 16th century. Kate Crosby notes that this attestation makes the tantric tradition earlier than "any other living meditation tradition in the contemporary Theravada world,"[13] predating the popular "New Burmese Satipatthana Method", better known as Vipassana meditation.

The anthropologist-historian S. J. Tambiah, however, has suggested a general pattern for that era, at least with respect to the relations between Buddhism and the sangha on the one hand and the king on the other hand. In Thailand, as in other Theravada Buddhist kingdoms, the king was in principle thought of as patron and protector of the religion (sasana) and the sangha, while sasana and the sangha were considered in turn the treasures of the polity and the signs of its legitimacy. Religion and polity, however, remained separate domains, and in ordinary times the organizational links between the sangha and the king were not close.[12]

Among the chief characteristics of Thai kingdoms and principalities in the centuries before 1800 were the tendency to expand and contract, problems of succession, and the changing scope of the king's authority. In effect, some Thai kings had greater power over larger territories, others less, and almost invariably a king who sought successfully to expand his power also exercised greater control over the sangha. That control was coupled with greater support and patronage of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. When a king was weak, however, protection and supervision of the sangha also weakened, and the sangha declined. This fluctuating pattern appears to have continued until the emergence of the Chakri Dynasty in the last quarter of the 18th century.[12]

Modern era

By the 19th century, and especially with the coming to power in 1851 of King Mongkut, who had been a monk himself for twenty-seven years, the sangha, like the kingdom, became steadily more centralized and hierarchical in nature and its links to the state more institutionalized. As a monk, Mongkut was a distinguished scholar of Pali Buddhist scripture. Moreover, at that time the immigration of numbers of monks from Burma was introducing the more rigorous discipline characteristic of the Mon sangha. Influenced by the Mon and guided by his own understanding of the Tipitaka, Mongkut began a reform movement that later became the basis for the Dhammayuttika order of monks. Under the reform, all practices having no authority other than custom were to be abandoned, canonical regulations were to be followed not mechanically but in spirit, and acts intended to improve an individual's standing on the road to nirvana but having no social value were rejected. This more rigorous discipline was adopted in its entirety by only a small minority of monasteries and monks. The Mahanikaya order, perhaps somewhat influenced by Mongkut's reforms but with a less exacting discipline than the Dhammayuttika order, comprised about 95 percent of all monks in 1970 and probably about the same percentage in the late 1980s. In any case, Mongkut was in a position to regularize and tighten the relations between monarchy and sangha at a time when the monarchy was expanding its control over the country in general and developing the kind of bureaucracy necessary to such control. The administrative and sangha reforms that Mongkut started were continued by his successor. In 1902 King Chulalongkorn (Rama V, 1868–1910) made the new sangha hierarchy formal and permanent through the Sangha Law of 1902, which remained the foundation of sangha administration in modern Thailand.[12] While Buddhism in Thailand remained under state centralization in the modern era, Buddhism experienced periods of tight state control and periods of liberalization depending on the government at the time.

Statistics

Approximately 94 percent of Thailand's population is Buddhist (five percent Muslim).[14] As of 2016 Thailand had 39,883 wats (temples). Three hundred-ten are royal wats, the remainder are private (public). There were 298,580 Buddhist monks, 264,442 of the Maha Nikaya order and 34,138 of the Dhammayuttika Nikaya order. There were 59,587 Buddhist novice monks.[15]

Influences

Three major forces have influenced the development of Buddhism in Thailand. The most visible influence is that of the Theravada school of Buddhism, imported from Sri Lanka. While there are significant local and regional variations, the Theravada school provides most of the major themes of Thai Buddhism. By tradition, Pāli is the language of religion in Thailand. Scriptures are recorded in Pāli, using either the modern Thai script or the older Khom and Tham scripts. Pāli is also used in religious liturgy, despite the fact that most Thais understand very little of this ancient language. The Pāli Tipiṭaka is the primary religious text of Thailand, though many local texts have been composed in order to summarise the vast number of teachings found in the Tipiṭaka. The monastic code (Pātimokkha) followed by Thai monks is taken from the Pāli Theravada Canon.

The second major influence on Thai Buddhism is Hindu beliefs received from Cambodia, particularly during the Sukhothai Kingdom. Hinduism played a strong role in the early Thai institution of kingship, just as it did in Cambodia, and exerted influence in the creation of laws and order for Thai society as well as Thai religion. Certain rituals practiced in modern Thailand, either by monks or by Hindu ritual specialists, are either explicitly identified as Hindu in origin, or are easily seen to be derived from Hindu practices. While the visibility of Hinduism in Thai society has been diminished substantially during the Chakri Dynasty, Hindu influences, particularly shrines to the god Brahma, continue to be seen in and around Buddhist institutions and ceremonies.

Folk religion—attempts to propitiate and attract the favor of local spirits known as phi—forms the third major influence on Thai Buddhism. While Western observers (as well as Western-educated Thais) have often drawn a clear line between Thai Buddhism and folk religious practices, this distinction is rarely observed in more rural locales. Spiritual power derived from the observance of Buddhist precepts and rituals is employed in attempting to appease local nature spirits. Many restrictions observed by rural Buddhist monks are derived not from the orthodox Vinaya, but from taboos derived from the practice of folk magic. Astrology, numerology, and the creation of talismans and charms also play a prominent role in Buddhism as practiced by the average Thai—practices that are censured by the Buddha in Buddhist texts (see Digha Nikaya 2, ff).

Additionally, more minor influences can be observed stemming from contact with Mahayana Buddhism. Early Buddhism in Thailand is thought to have been derived from an unknown Mahayana tradition. While Mahayana Buddhism was gradually eclipsed in Thailand, certain features of Thai Buddhism—such as the appearance of the bodhisattva Lokeśvara in some Thai religious architecture, and the belief that the king of Thailand is a bodhisattva himself—reveal the influence of Mahayana concepts.

The only other bodhisattva prominent in Thai religion is Maitreya, often depicted in Budai form, and often confused with Phra Sangkajai (Thai: พระสังกัจจายน์), a similar but different figure in Thai Buddhist folklore. Images of one or both can be found in many Thai Buddhist temples, and on amulets as well. Thai may pray to be reborn during the time of Maitreya, or dedicate merit from worship activities to that end.

In modern times, additional Mahayana influence has stemmed from the presence of Overseas Chinese in Thai society. While some Chinese have "converted" to Thai-style Theravada Buddhism, many others maintain their own separate temples in the East Asian Mahayana tradition. The growing popularity of Guanyin, a form of Avalokiteśvara, may be attributed to the Chinese presence in Thailand.

Government ties

While Thailand is a constitutional monarchy, it inherited a strong Southeast Asian tradition of Buddhist kingship that tied the legitimacy of the state to its protection and support for Buddhist institutions. This connection has been maintained into the modern era, with Buddhist institutions and clergy being granted special benefits by the government, as well as being subjected to a certain amount of governmental oversight. Part of the coronation of the Thai monarch includes the king proceeding to the chapel royal (the Wat Phra Kaew) to vow to be a "defender of the faith" in front of a chapter of monks including the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand.

In addition to the ecclesiastical leadership of the sangha, a secular government ministry supervises Buddhist temples and monks. The legal status of Buddhist sects and reform movements has been an issue of contention in some cases, particularly in the case of Santi Asoke, which was legally forbidden from calling itself a Buddhist denomination, and in the case of the ordination of women attempting to revive the Theravada bhikkhuni lineage have been prosecuted for attempting to impersonate members of the clergy.

To obtain a passport for travel abroad, a monk must have an official letter from Sangha Supreme Council granting the applicant permission to travel abroad; Buddhist monk identification card; a copy of house or temple registration; and submit any previous Thai passport or a certified copy.[16]

In addition to state support and recognition—in the form of formal gifts to monasteries made by government officials and the royal family (for example, Kathin)—-a number of special rights are conferred upon Buddhist monks. They are granted free passage on public transportation, and most train stations and airports have special seating sections reserved for members of the clergy. Conversely, ordained monastics are forbidden from standing for office or voting in elections.

Calls for state religion

In 2007, calls were made by some Buddhist groups for Buddhism to be recognized in the new national constitution as the state religion. This suggestion was initially rejected by the committee charged with drafting the new constitution.[17] This move prompted protests from supporters of the initiative, including a number of marches on the capital and a hunger strike by twelve Buddhist monks.[18] Some critics of the plan, including scholar and social critic Sulak Sivaraksa, claimed that the movement to declare Buddhism the national religion is motivated by political gain, manipulated by supporters of ousted Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra.[18] The Constitution Drafting Committee later voted against the special status of Buddhism, provoking religious groups. They condemned the committee and the draft constitution.[19] On 11 August 2007, Sirikit, the Queen of Thailand, expressed her concern over the issue. She said, in her birthday speech, that Buddhism is beyond politics. Some Buddhist organizations halted their campaigns the next day.[20]

Government service

No law directly prohibits a member of the Buddhist institutions, such as a monk, a novice and a nun, from being a candidate in an examination for recruitment of government officers. Though both the Council of Ministers and the Sangha Supreme Council, the supervising body of the Thai Buddhist communities, have ordered such prohibition on grounds of appropriateness, according to the Memorandum of the Cabinet's Administrative Department No. NW98/2501 dated 27 June 1958 and the Order of the Sangha Supreme Council dated 17 March 1995.[21]

Elections

The members of the Buddhist community and the communities of other religions are not entitled to elect or be elected as a holder of any government post. For instance, the 2007 constitution of Thailand disfranchises "a Buddhist monk, a Buddhist novice, a priest or a clergy member" (Thai: "ภิกษุ สามเณร นักบวช หรือนักพรต").[22]

The Sangha Supreme Council also declared the same prohibition, pursuant to its Order dated 17 March 1995.[23] At the end of the Order was a statement of grounds given by Nyanasamvara, the Supreme Patriarch. The statement said:

The members of the Buddhist community are called samaṇa, one who is pacified, and also pabbajita, one who refrains from worldly activities. They are thus needed to carefully conduct themselves in a peaceful and unblamable manner, for their own sake and for the sake of their community. ... The seeking of the representatives of the citizens to form the House of Representatives is purely the business of the State and specifically the duty of the laity according to the laws. This is not the duty of the monks and novices who must be above the politics. They are therefore not entitled to elect or be elected. And, for this reason, any person who has been elected as a Representative will lose his membership immediately after becoming a Buddhist monk or novice. This indicates that the monkhood and noviceship are not appropriate for politics in every respect.[23]

When a monk or novice is involved in or supports an election of any person..., the monk or novice is deemed to have breached the unusual conduct of pabbajita and brought about disgrace to himself as well as his community and the Religion. Such a monk or novice would be condemned by the reasonable persons who are and are not the members of this Religion. A pabbajita is therefore expected to stay in impartiality and take a pity on every person...without discrimination. Moreover, the existence of both the monks and the Religion relies upon public respect. As a result, the monks and novices ought to behave in such a way that deserves respect of the general public, not merely a specific group of persons. A monk or novice who is seen by the public as having failed to uphold this rule would then be shunned, disrespected and condemned in various manners, as could be seen from many examples.[23]

Under the NCPO

Buddhism in Thailand came under greater state control following the 2014 coup d'état. After seizing power the military junta, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), set up a National Reform Council with a religious committee led by former Thai senator Paiboon Nititawan and former monk Mano Laohavanich. Calls for reform were spearheaded by right-wing activist monk Phra Buddha Issara, who had close ties with junta leader Prayut Chan-o-cha,[24] and was known for leading the protests in Bangkok that led to the coup.[25][26][27]

State influence over several aspects of Thai Buddhism increased under the NCPO, with the junta's new constitution stating that the Thai government is to directly support Theravada Buddhism specifically.[28][29] In 2015, the junta's National Reform Council made several proposals to give the state greater control of Buddhism, including requiring temples to open their finances to the public, ending short-term ordinations, requiring monks to carry smart cards to identify their legal and religious backgrounds, increased control of the bank accounts of temples, increased control of monastic disciplinarians, changing the abbots of all temples every five years, putting the Ministry of Culture in charge of controlling all temple assets, controlling monastic education, and taxing monks.[30][31][32][33][34][35]

In 2016, Phra Buddha Issara requested that the Department of Special Investigation (DSI) investigate the assets of Thailand's leading monks, the Sangha Supreme Council.[25][36] This resulted in an alleged tax evasion scandal against Somdet Chuang, the most senior member of the council who was next in line to become supreme patriarch. Although prosecutors did not charge Somdet,[37] the incident postponed his appointment and led to a change in the law that allowed the Thai government to bypass the Sangha Supreme Council and appoint the supreme patriarch directly.[33][38] This allowed the ruling junta to effectively handpick Thailand's supreme patriarch.[38][39][40] In 2017, Somdet Chuang's appointment was withdrawn, with a monk from the Dhammayuttika Nikaya appointed instead. The appointment was made by King Rama X, who chose the name from five given to him by NCPO leader Prayut Chan-o-cha.[33][38][39]

In February 2017, the junta used Article 44, a controversial section in the interim constitution, to replace the head of the National Office of Buddhism with a DSI official.[41] The DSI official was removed from office a few months later after religious groups called on the government to fire him because of his reform plans, but was reinstated after a few months.[42][43]

In May 2018, the NCPO launched simultaneous raids of four different temples to arrest several monks shortly after a crackdown on protesters on the anniversary of the coup.[44][45] To the surprise of many officials, one of the monks arrested was Phra Buddha Issara.[46] The right-wing monk was arrested for charges brought against him in 2014, including alleged robbery and detaining officials, however, his most serious charge was a charge of unauthorized use of the royal seal filed in 2017.[46][47][48] Police did not state why he was then being arrested for charges filed as far back as four years.[46] One observer described the arrest of Buddha Issara as trying to cover up the true motives or because Buddha Issara knew too much about the rulers and was seen as a threat.[49] Another said that the junta may regard him as a loose canon politically and that the junta is virtue signaling—deserving continued political power—to the new Thai monarch, King Maha Vajiralongkorn.[50] All the monks arrested in the May raids were defrocked shortly after being taken into custody, and detained before trial.[51][note 1]

Anthropologist Jim Taylor argues that the arrests were the "ruling palace regime" trying to consolidate royalist power by eliminating non-royalist high-ranking monks. Taylor pointed out that the suspects of the investigations were innocent until proven guilty, yet were all defrocked before trial and stripped of decades of monastic seniority only for being accused of the crimes. The only royalist monk arrested was Buddha Issara.[49] In July 2018, the junta passed a law giving the Thai king the ability to select members of the Sangha Supreme Council, the governing body of Thai monks, instead of the monks themselves. The alleged scandals of the 2017–18 Thai temple fraud investigations and the resulting arrests were cited as the reason for the change.[53]

Ordination and clergy

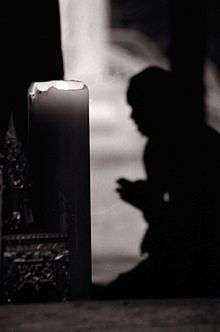

As in most other Theravada nations, Buddhism in Thailand is represented primarily by the presence of Buddhist monks, who serve as officiants on ceremonial occasions, as well as being responsible for preserving and conveying the teachings of the Buddha.

During the latter half of the 20th century, most monks in Thailand began their careers by serving as temple boys (Thai: เด็กวัด dek wat, "children of the wat"). Temple boys are traditionally no younger than eight and do minor housework. The primary reason for becoming a temple boy is to gain a basic education, particularly in basic reading and writing and the memorization of the scriptures chanted on ritual occasions. Prior to the creation of state-run primary schools in Thailand, village temples served as the primary form of education for most Thai boys. Service in a temple as a temple boy was a necessary prerequisite for attaining any higher education, and was the only learning available to most Thai peasants. Since the creation of a government-run educational apparatus in Thailand, the number of children living as temple boys has declined significantly. However, many government-run schools continue to operate on the premises of the local village temple.

Boys now typically ordain as a sāmaṇera or novitiate monks (Thai: สามเณร samanen, often shortened to nen Thai: เณร). In some localities, girls may become sāmaṇerī. Novices live according to the Ten Precepts but are not required to follow the full range of monastic rules found in the Pātimokkha. There are a few other significant differences between novices and bhikkhus. Novices often are in closer contact with their families, spending more time in the homes of their parents than monks. Novices do not participate in the recitation of the monastic code (and the confessions of violations) that take place on the uposatha days. Novices technically do not eat with the monks in their temple, but this typically only amounts to a gap in seating, rather than the separation observed between monks and the laity. Novices usually ordain during a break from secular schooling, but those intending on a religious life, may receive secular schooling at the wat.

Young men typically do not live as a novice for longer than one or two years. At the age of 20, they become eligible to receive upasampada, the higher ordination that establishes them as a full bhikkhu. A novice is technically sponsored by his parents in his ordination, but in practice in rural villages the entire village participates by providing the robes, alms bowl, and other requisites that will be required by the monk in his monastic life.

Temporary ordination is the norm among Thai Buddhists. Most young men traditionally ordain for the term of a single vassa or rainy season (Thai phansa). Those who remain monks beyond their first vassa typically remain monks for between one and three years, officiating at religious ceremonies in surrounding villages and possibly receiving further education in reading and writing (possibly including the Khom or Tai Tham alphabets traditionally used in recording religious texts). After this period of one to three years, most young monks return to secular life, going on to marry and start a family. Young men in Thailand who have undergone ordination are seen as being more suitable partners for marriage; unordained men are euphemistically called "unripe", while those who have been ordained are said to be "ripe". A period as a monk is a prerequisite for many positions of leadership within the village hierarchy. Most village elders or headmen were once monks, as were most traditional doctors, spirit priests, and some astrologists and fortune tellers.

In a country where most males can be ordained as monks for even short periods of time, the experience can be profitable. The Thai musician, Pisitakun Kuantalaeng, became a monk for a short period following the death of his father in order to make merit. He observed that, "Being a monk is good money,...When you go and pray you get 300 baht [about £7] even though you have no living expenses, and you can go four times a day. Too many monks in Thailand do it to get rich. If you become a monk for three months you have enough money for a scooter."[54]

Monks who do not return to secular life typically specialize in either scholarship or meditation. Those who specialize in scholarship typically travel to regional education centers to begin further instruction in the Pāli language and the scriptures, and may then continue on to the major monastic universities in Bangkok. The scholarship route is also followed by monks who desire to rise in the ecclesiastic hierarchy, as promotions within the government-run system are contingent on passing examinations in Pāli and Dhamma studies.

The Thai tradition supports laymen to go into a monastery, dress and act as monks, and study while there. The time line is based on threes, staying as a monk for three days, or three weeks, or three months or three years, or three weeks and three days. This retreat is expected of all Thai males, rich or poor, and often is scheduled after high school. Such retreats bring honor to the family and blessings (merit) to the young man. Thais make allowances for men who follow this practice, such as holding open a job.

Health issues

Rising obesity among monks[55] and concerns for their well-being has become an issue in Thailand. A study by the Health Ministry in 2017 of 200 Bangkok temples found that 60 percent of monks suffer from high cholesterol and 50 percent from high blood sugar.[56] Public health experts attribute this to two factors. First, monks are required to accept and eat whatever is given to them on their daily alms rounds. Second, monks are not permitted to engage in cardiovascular exercise as it is undignified. Monks eat only two meals per day, breakfast and lunch. But the remainder of the day they are allowed to drink nam pana, which includes the juice of fruit less than fist-sized, often high in sugar. To combat the high rate of non-communicable diseases among monks, the National Health Commission Office (NHCO) issued a pamphlet, National Health Charter for Monks,[57] designed to educate monks and laypeople alike as to healthy eating habits.[56]

Controversies

The Thai media often reports on Buddhist monks behaving in ways that are considered inappropriate.[58] There have been reports of sexual assault, embezzlement, drug-taking, extravagant lifestyles, even murder. Thailand's 38,000 temples, populated by 300,000 monks, are easy targets for corruption, handling between US$3 to 3.6 billion yearly in donations, mostly untraceable cash.[59] In a case that received much media attention, Luang Pu Nen Kham Chattiko was photographed in July 2013 wearing Ray-Ban sunglasses, holding a Louis Vuitton bag full of US dollars, and "...was later found to be a trafficker of methamphetamines, an abuser of women and the lover of a pregnant fourteen-year-old."[60][61]

There have been cases of influential monks persecuted and jailed by the Thai government, through verdicts later declared moot or controversial. A well-known case in Thailand is that of Phra Phimontham, then abbot of Wat Mahadhatu, known in Thailand for having introduced the Burmese Satipatthana meditation method to Thailand. In 1962, during the Cold War, he was accused of collaboration with communist rebels and being a threat to national security, and was fully defrocked and jailed. In fact, the government persecuted him because of his political views and promotion of changes in the Sangha. Phra Phimontham had strong pro-democratic leanings, which did not comport well with the regime of the day nor the palace. Furthermore, Phra Phimontham was part of the Maha Nikaya fraternity, rather than the Dhammayuttika fraternity, which the government and monarchy historically have preferred. Phra Phimontham was likely to become the next supreme patriarch.[62]:39–41[63]:638 For this reason, his treatment has been described by Thai scholars as a "struggle between patriarchs" (Thai: ศึกสมเด็จ), referring to the political objective of disabling him as a candidate.[64] After four years, when the country changed its government, Phra Phimontham was released from prison when a military court decided he had not collaborated with communists after all. Afterwards, he ordained again and eventually regained his former status, though he continued to be discredited.[62]:39–41[65][66]

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu was subject to similar allegations from the Thai government, and so was Luang Por Phothirak, the founder of Santi Asoke. Luang Por Pothirak was eventually charged of altering the Vinaya and defrocked. A recent example is Phra Prajak Kuttajitto, an environmentalist monk critical of government policies, who was arrested and defrocked.[62]:39–41

In 1999[67][68] and again in 2002,[69][70] Luang Por Dhammajayo, the then abbot of Wat Phra Dhammakaya, was accused of charges of fraud and embezzlement by the Thai media and later some government agencies when donations of land were found in his name. Wat Phra Dhammakaya denied this, stating that it was the intention of the donors to give the land to the abbot and not the temple, and that owning personal property is common and legal in the Thai Sangha.[65]:139[71][72] Widespread negative media coverage at this time was symptomatic of the temple being made the scapegoat for commercial malpractice in the Thai Buddhist temple community[73][74] in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[75][76] The Sangha Supreme Council declared that Luang Por Dhammajayo had not broken any serious offenses against monastic discipline (Vinaya).[77] In 2006, the Thai National Office for Buddhism cleared the Dhammakaya Foundation and Luang Por Dhammajayo of all accusations[78] when Luang Por Dhammajayo agreed offer all of the disputed land to the name of his temple.[79]

In March 2016, Thai police formally summoned then Acting Supreme Patriarch Somdet Chuang Varapunno, after he refused to answer direct questions about his vintage car, one of only 65 made. The car was part of a museum kept at Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen in Bangkok, but has now been seized by police investigating possible tax evasion. Somdet reportedly transferred ownership of the vehicle to another monk after the scandal broke. He refused to answer police questions directly, insisting that written questions be sent to his lawyer. He did say that the car was a gift from a follower.[80]

Analysts from different news outlets have pointed out that the actions of the Thai government towards Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen may have reflected a political need to control who should be selected as the next Supreme Patriarch, since Somdet had already been proposed as a candidate by the Sangha Supreme Council. Selecting him would mean a Supreme Patriarch from the Maha Nikaya fraternity, rather than the Dhammayuttika fraternity, which historically has always been the preferred choice of the Thai government and the monarchy.[63]:638 In fact, Somdet Chuang's nomination was postponed and eventually withdrawn after the Thai government changed the law in December 2016 to allow King Vajiralongkorn to appoint the Supreme Patriarch directly, with Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha countersigning, leading to the appointment of a monk from the Dhammayuttika fraternity instead.[81][82] The Thai government cited several reasons for this, including the car.[83][84] At the end of the same year, however, prosecutors decided not to charge Somdet Chuang, but to charge his assistant abbot instead, and another six people who had part in importing the vintage car.[85] In February 2016, in a protest organized by the National Centre for the Protection of Thai Buddhism, a Red Shirt-oriented network, the example of Phra Phimontham was also cited as demands were made for the Thai government to no longer involve itself with the selection of the next leader of the Sangha.[63][86]

Reform movements

- The Dhammayuttika Nikaya (Thai: ธรรมยุตนิกาย) began in 1833 as a reform movement led by Prince Mongkut, son of King Rama II of Siam. It remained a reform movement until passage of the Sangha Act of 1902, which formally recognized it as the lesser of Thailand's two Theravada denominations.[87] Mongkut was a bhikkhu under the name of Vajirañāṇo for 27 years (1824–1851) before becoming King of Siam (1851–1868). In 1836 he became the first abbot of Wat Bowonniwet Vihara. After the then 20-year-old prince entered monastic life in 1824, he noticed what he saw as serious discrepancies between the rules given in the Pāli Canon and the actual practices of Thai bhikkhus and sought to upgrade monastic discipline to make it more orthodox. Mongkut also made an effort to remove all non-Buddhist, folk religious, and superstitious elements which over the years had become part of Thai Buddhism.[88] Dhammayuttika monks were expected to eat only one meal a day (not two) that was to be gathered during a traditional alms round.

- The Dhammakaya Movement is a Thai Buddhist tradition which was started by Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro in the early 20th century.[89] The tradition is revivalist in nature and practices Dhammakaya meditation. The movement opposes traditional magical rituals, superstition, folk religious practices, fortune telling and giving lottery numbers, and focuses on an active style of propagating and practicing meditation. Features of the tradition include teaching meditation in a group, teaching meditation during ceremonies, teaching meditation simultaneously to monastics and lay people, teaching one main meditation method and an emphasis on lifelong ordination.[65]

- The Santi Asoke (Thai: สันติอโศก "Peaceful Asoka") or Chao Asok ("People of Asoka") was established by Phra Bodhirak after he "declared independence from the Ecclesiastical Council (Sangha) in 1975".[90] Santi Asoke has been described as "a transformation of the "forest monk" revival of [the 1920s and 1930s]" and "is more radical [than the Dhammakaya Movement] in its criticism of Thai society and in the details of its own vision of what constitutes a truly religiomoral community."[89]

- The Sekhiya Dhamma Sangha are a group of activist monks focusing on modern issues in Thailand (i.e., deforestation, poverty, drug addiction, and AIDS). The group was founded in 1989 among a growth of Buddhist social activism in Thailand in the latter half of the 20th century. While criticized for being too concerned and involved with worldly issues, Buddhist social activists cite duty to the community as justification for participation in engaged Buddhism[91]

Position of women

Unlike in Burma and Sri Lanka, the bhikkhuni lineage of women monastics was never established in Thailand. Women primarily participate in religious life either as lay participants in collective merit-making rituals or by doing domestic work around temples. A small number of women choose to become maechi, non-ordained religious specialists who permanently observe either the Eight or Ten Precepts. Maechi do not receive the level of support given to bhikkhu and their position in Thai society is the subject of some discussion.

There have been efforts to attempt to introduce a bhikkhuni lineage in Thailand as a step towards improving the position of women in Thai Buddhism. The main proponent of this movement has been Dhammananda Bhikkhuni.[92] Unlike similar efforts in Sri Lanka, these efforts have been extremely controversial in Thailand.[93] Women attempting to ordain have been accused of attempting to impersonate monks (a civil offense in Thailand), and their actions have been denounced by many members of the ecclesiastic hierarchy.

In 1928 a secular law was passed in Thailand banning women's full ordination in Buddhism. Varanggana Vanavichayen became the first female monk to be ordained in Thailand in 2002.[94] Some time after this, the secular law was revoked. On 28 February 2003,[95] Dhammananda Bhikkhuni received full monastic ordination as a bhikkhuni of the Theravada tradition in Sri Lanka, making her the first modern Thai woman to receive full ordination as a Theravada bhikkhuni.[96][97][98] She is Abbess of Songdhammakalyani Monastery, the only temple in Thailand where there are bhikkhunis.[99] It was founded by her mother, Voramai, a Mahayana bhikkhuni, in the 1960s.[92]

No one denies that men and women have an equal chance to attain enlightenment. In Mahayana Buddhism, practised in Taiwan, mainland China, Hong Kong, and Tibet, female ordinations are common, but in countries that adhere to the Theravada branch of the religion, such as Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Myanmar, women were banned from becoming ordained about eight centuries ago, "for fear that women entering monastic life instead of bearing children would be a disruption of social order", according to Kittipong Narit, a Buddhist scholar at Bangkok's Thammasat University.[60] Critics charge that the ban on female ordination is about patriarchy and power. The status quo benefits those in power and they refuse to share the perks with outsiders.[100]

Most objections to the reintroduction of a female monastic role hinge on the fact that the monastic rules require that both five ordained monks and five ordained bhikkhunis be present for any new bhikkhuni ordination. Without such a quorum, critics say that it is not possible to ordain any new Theravada bhikkhuni. The Thai hierarchy refuses to recognize ordinations in the Dharmaguptaka tradition (the only currently existing bhikkhuni ordination lineage) as valid Theravada ordinations, citing differences in philosophical teachings and, more critically, monastic discipline.

Notes

- Thai law states that monks cannot be jailed, therefore any monk taken into custody must be defrocked if denied release on bail, even before guilt is determined.[52]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buddhism in Thailand. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Meditation in Thailand. |

- Religion in Thailand

- Anagarika laity

- Buddha images in Thailand

- Thai funeral

- Luang Pu Thuat

- Mahasati meditation

References

- "Population by religion, region and area, 2015" (PDF). NSO. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "Population by religion, region and area, 2015" (PDF). NSO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- "Population by religion, region and area, 2015" (PDF). NSO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- "Population by religion, region and area, 2015" (PDF). NSO. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-07-03. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- "CIA World Factbook: Thailand". Central Intelligence Agency. 2007-02-08. Archived from the original on 2015-07-03. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- 'Lamphun's Little-Known Animal Shrines' in: Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 1. Chiang Mai ,Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- Bunker, Emma C. (1971). "Pre-Angkor Period Bronzes from Pra Kon Chai". Archives of Asian Art. 25: 67–76. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111032.

- "Some Aspects of Asian History and Culture" by Upendra Thakur p.157

- Sujato, Bhante (2012), Sects & Sectarianism: The Origins of Buddhist Schools, Santipada, p. 72, ISBN 9781921842085

- Gombrich, Richard F. (2006). Theravāda Buddhism : a social history from ancient Benares to modern Colombo (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-415-36509-3.

- Tuchrello, William P. "The Society and Its Environment" (Religion: Historical Background section). Thailand: A Country Study. Archived 2007-11-14 at the Wayback Machine Federal Research Division, Library of Congress; Barbara Leitch LePoer, ed. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Archived 2012-07-10 at Archive.today

- Kate Crosby, Traditional Theravada Meditation and its Modern-Era Suppression. Hong Kong: Buddhist Dharma Centre of Hong Kong, 2013, ISBN 978-9881682024

- "Major Religions in Thailand". worldatlas. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- "Educational Statistics 2016". Ministry of Education Thailand (MOE). p. 14. Archived from the original on 2018-07-29. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Ministry of Foreign Affairs – required documents". Archived from the original on 2015-07-09. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- Charoensuthipan, Penchan (18 April 2007). "Thai Buddhists call for top status 'unnecessary'". The Buddhist Channel. Archived from the original on 2007-05-09. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- Monks push for Buddhism to be named Thailand's religion Archived 16 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Osathanon, Prapasri; Nerisa Nerykhiew (2007-07-01). "Drafters reject Buddhism as State Religion". The Nation. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- "Buddhist groups, monks halt campaigns against draft charter". The Nation. 2007-08-12. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ประกาศสำนักงานสภาความมั่นคงแห่งชาติ ลงวันที่ 21 พฤศจิกายน 2556 [Announcement of the National Security Council Office dated 21 November 2013] (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: National Security Council. Dec 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-12-07. Retrieved 2014-01-22.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Section 100 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, Buddhist Era 2550 (2007)". Asian Legal Information Institute. 2007. Archived from the original on 2012-05-15. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- Matichon (2007-06-16). หมายเหตุคำสั่งมหาเถรสมาคม พ.ศ. 2538 [A statement of grounds attached to the 1995 Order of the Sangha Supreme Council] (in Thai). Sanook!. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- Fifield, Anna. "Thai Buddhist monk wants to clean up his country's religious institutions". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- Dubus, Arnaud (22 June 2016). "Controverse autour du temple bouddhique Dhammakaya: un bras de fer religieux et politique" [Controversy regarding the Dhammakaya Buddhist temple: A religious and political standoff]. Églises d'Asie (in French). Information Agency for Foreign Missions of Paris. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ธรรมกายแจงปมภัยศาสนา [Dhammakaya responds to issues that threaten [Buddhist] religion] (in Thai). Thai News Agency. 3 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-03-18. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Tan Hui Yee (25 February 2016). "Tense times for Thai junta, Buddhist clergy". The Straits Times. Singapore Press Holdings. Archived from the original on 2016-11-16. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "Can Thailand tolerate more than one form of Buddhism?". New Mandala. 2016-12-01. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- Chaichalearmmongkol, Nopparat (2016-08-04). "5 Things to Know About Thailand's Proposed Constitution". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2017-11-21. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- "Government plans smart cards for monks". Bangkok Post. 6 June 2016. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- "Monk reform no easy task". Bangkok Post. 7 Jun 2016. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- "Thai junta seeks to force temples to open their finances". Reuters. 16 Jun 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- "Somdet Phra Maha Muniwong new Supreme Patriarch". Bangkok Post. 7 February 2017. Retrieved 2017-02-09.

- เปิดรับฟังความเห็นคณะสงฆ์ ประเด็นปฏิรูปพุทธศาสนา 6 แนวทาง [Listening to the Sangha's opinion about 6 ways to reform Buddhism]. Matichon (in Thai). 17 June 2015. p. 27. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 24 January 2017 – via Matichon E-library.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "The perplexing case of Wat Dhammakaya". New Mandala. 2017-03-06. Archived from the original on 2017-03-08. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- Dubus, Arnaud (18 January 2016). "La Thaïlande se déchire à propos de la nomination du chef des bouddhistes" [Thailand is torn about the appointment of a Buddhist leader]. Églises d'Asie (in French). Information Agency for Foreign Missions of Paris. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- สั่งไม่ฟ้อง "หลวงพี่แป๊ะ" คดีรถโบราณหรูสมเด็จช่วง ชี้ไม่มีหลักฐานรู้เห็นเอกชนเสียภาษีไม่ถูกต้อง. Thai PBS (in Thai). 2017-01-12. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- "NLA passes Sangha Act amendment bill". The Nation. 29 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-12-30. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- Constant, Max (29 December 2016). "Thai junta restores law allowing king to pick top monk". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 2016-12-30. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- "Sangha Act set to pass". The Nation. 29 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-12-30. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- "Thai junta replaces director of Buddhism department with policeman". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Tanakasempipat, Patpicha; Niyomyat, Aukkarapon (29 August 2017). "Thailand's Buddhism chief removed after pressure from religious groups". Reuters. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Cheunprasang, Paisal (2017-09-27). "Pongporn returns as National Buddhism Office head after row". Asia News Network. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- "Buddha Issara Followers Fume at Defrocked Monk's Arrest". Khaosod English. 2018-05-25. Archived from the original on 2018-05-25. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- Wongcha-um, by Panu (2018-05-25). "Thailand raids temples, arrest monks in fight to clean up Buddhism". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2018-05-25. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- "Buddha Issara Accused of Royal Forgery". Khaosod English. 2018-05-24. Archived from the original on 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- "Buddha Issara Arrested in Dawn Raid". Khaosod English. 2018-05-24. Archived from the original on 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- "Thailand arrests senior monks in temple raids to clean up Buddhism" (Editorial). Reuters. Archived from the original on 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- Taylor, Jim (8 June 2018). "What's behind the 'purging' of the Thai sangha?". New Mandala. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (26 June 2018). "Thailand's junta renews corruption crackdown on Buddhist monks". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2018-06-26. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Ngamkham, Wassayos (25 May 2018). "Senior monks defrocked after raids". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- "Phra Buddha Isara disrobed, detained". Bangkok Post. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- Theppajorn, Khanittha; Chanwanpen, Kas. "King to appoint, oversee new Sangha council". The Nation. Archived from the original on 2018-07-25. Retrieved 2018-07-25.

- Watling, Eve (3 March 2018). "Noise As Abstraction: Fuzzing The Limits Of Free Speech In Thailand". The Quietus. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Suhartono, Muktita (2018-08-12). "In Thailand, 'Obesity in Our Monks Is a Ticking Time Bomb'". New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Pisuthipan, Arusa (3 September 2018). "The robes are getting tight". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Saeiew, Khanitta. "Health Charter for Buddhist Monks, established healthy monks, temples and happy communities in 10 years". National Health Commission Office (Thailand). Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Sanyanusin, Patcharawalai (30 July 2018). "Crisis of faith within Buddhism?". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Fifield, Anna (2015-05-15). "Hardliner tries to reform Thailand's Buddhist monks behaving badly". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2015-05-22. Retrieved 16 May 2015 – via The Guardian.

- "Thai TV anchor turned monk fights for women's right to be ordained". South China Morning Post. 2015-05-10. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Ehrlich, Richard S (14 August 2018). "Thailand tackles its bad boy Buddhist monks". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 2018-08-14. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- Scott, Rachelle M (2009). Nirvana for Sale? Buddhism, Wealth, and the Dhammakāya Temple in Contemporary Thailand. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4416-2410-9.

- McCargo, Duncan (2012). "The Changing Politics of Thailand's Buddhist Order". Critical Asian Studies. Routledge. 44 (4): 627–642. doi:10.1080/14672715.2012.738544. ISSN 1467-2715.

- Fuengfusakul, Apinya (1998). ศาสนาทัศน์ของชุมชนเมืองสมัยใหม่: ศึกษากรณีวัดพระธรรมกาย [Religious Propensity of Urban Communities: A Case Study of Phra Dhammakaya Temple] (in Thai). Chulalongkorn University: Buddhist Studies Center. pp. 101–2.

- Newell, Catherine Sarah (2008). Monks, Meditation and Missing Links: Continuity, 'Orthodoxy' and the Vijja Dhammakaya in Thai Buddhism. London: Department of the Study of Religions School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- พระพิมลฯผจญมารคดีประวัติศาสตร์วงการสงฆ์ [Phra Phimontham Confronts the Devil: A Historical Case in the World of the Sangha]. Kom Chad Luek. The Nation Group. 2009-12-11. Archived from the original on 2016-09-21. Retrieved 20 August 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "'I Will Never Be Disrobed' says Thai abbot of Dhammakaya Temple", and "Between Faith and Fund-Raising", Asiaweek 17 September 1999

- Liebhold, David (28 July 1999). "Trouble in Nirvana: Facing charges over his controversial methods, a Thai abbot sparks debate over Buddhism's future". Time Asia. Archived from the original on 2009-06-25. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Yasmin Lee Arpon (2002) Scandals Threaten Thai Monks' Future SEAPA 11 July 2002

- Controversial monk faces fresh charges The Nation 26 April 2002

- "Frequently Asked Questions – Dhammakaya Foundation". Dhammakaya Foundation. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- PR Department Team (19 December 1998). เอกสารชี้แจงฉบับที่ 2/2541-พระราชภาวนาวิสุทธิ์กับการถือครองที่ดิน [Announcement 2/2541-Phrarajbhavanavisudh and land ownership]. www.dhammakaya.or.th (in Thai). Patumthani: Dhammakaya Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 March 2005.

- Wiktorin, Pierre (2005) De Villkorligt Frigivna: Relationen mellan munkar och lekfolk i ett nutida Thailand (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International) p.137 ISSN 1653-6355

- Julian Gearing (1999) Buddhist Scapegoat?: One Thai abbot is taken to task, but the whole system is to blame Asiaweek 30 December 1999 Archived 2009-06-25 at the Wayback Machine<

- Bangkokbiznews 24 June 2001 p.11

- "Matichon 19 July 2003". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- Udomsi, Sawaeng (2000). "รายงานการพิจารณาดำเนินการ กรณีวัดพระธรรมกาย ตามมติมหาเถรสมาคม ครั้งที่ ๓๒/๒๕๔๑" [Report of Evaluation of the Treatment of the Case Wat Phra Dhammakaya -- Verdict of the Supreme Sangha Council 32/2541 B.E.]. วิเคราะห์นิคหกรรม ธรรมกาย [Analysis of Disciplinary Transactions of Dhammakaya] (in Thai). Bangkok. pp. 81–85. ISBN 974-7078-11-2.

- "Bangkok Post 23 August 2006". Archived from the original on 2016-09-03. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- "Thailand | Thai court spares founder of Dhammakaya". Buddhist Channel. 2006-08-23. Archived from the original on 2016-09-03. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- Cochrane, Liam (2016-03-29). "Thailand's head monk to be summoned by police over luxury Mercedes-Benz". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Sydney. Archived from the original on 2016-03-29. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- สัมภาษณ์สด เจ้าคุณประสาร-ส.ศิวรักษ์ แก้พรบ.สงฆ์ [Live interview with Chao Khun Prasarn and S. Sivaraksa about amending the Monastic Act]. New TV (in Thai). 27 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-02-10. Retrieved 4 February 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Somdet Phra Maha Muneewong appointed new supreme patriarch". The Nation. 7 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-02-08. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Tanakasempipat, Patpicha; Kittisilpa, Juarawee; Thepgumpanat, Panarat (2016-04-22). Lefevre, Amy Sawitta (ed.). "Devotees at Thai temple give alms to tens of thousands of Buddhist monks". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2016-11-14. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- "Men-at-alms". The Economist. 2016-04-02. Archived from the original on 2016-08-20. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- เลื่อนสั่งคดีครั้งแรก รถโบราณสมเด็จช่วง [First hearing vintage car Somdet Chuang postponed]. Kom Chad Luek. The Nation Group. 25 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-12-25. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- Wongcha-um, Panu (5 February 2016). "Thai monks protest against state interference in Buddhist governance". Channel News Asia. Mediacorp Pte Ltd. Archived from the original on 2016-08-31. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- Buddhism in Contemporary Thailand Archived 2015-04-01 at the Wayback Machine, Prof. Phra Thepsophon, Rector of Mahachulalongkorn Buddhist University. Speech at the International Conference on Buddhasasana in Theravada Buddhist countries: Issue and The Way Forward in Colombo, Sri Lanka, January 15, 2003, Buddhism in Thailand, Dhammathai – Buddhist Information Network

- Ratanakosin Period Archived 2015-05-21 at the Wayback Machine, Buddhism in Thailand, Dhammathai – Buddhist Information Network

- Marty, Martin E.; Appleby, R. Scott, eds. (1994). Fundamentalisms Observed (Pbk. ed., 2. [Dr.]. ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 668. ISBN 978-0-226-50878-8.

- Sanitsuda Ekachai. "The Man behind Santi Asoke". Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- Cantwell, Cathy; Kawanami, Hiroko, eds. (2001). Religions in the Modern World (Paper, 2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-415-45891-7.

- Willis, Jan (2013-01-21). "Building a Place for the Theris". Lion's Roar. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27. Retrieved 21 Apr 2015.

- Kurz, Sopaporn (2007-07-22). "Bhikkhuni says she is glum on future of ordination". The Nation. The Buddhist Channel. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 21 Apr 2015.

- Sommer, Jeanne Matthew. "Socially Engaged Buddhism in Thailand: Ordination of Thai Women Monks". Warren Wilson College. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Kristin Barendsen. "Ordained at Last". Archived from the original on February 6, 2004. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- archive.org:"Ordained at Last by Kristin Barendson". Archived from the original on 2004-02-06. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- สุวิดา แสงสีหนาท, นักบวชสตรีไทยในพระพุทธศาสนา พลังขับเคลื่อนคุณธรรมสู่สังคม, ศูนย์ส่งเสริมและพัฒนาพลังแผ่นดินเชิงคุณธรรม, 1999, page 45-6 (in Thai)

- Gemma Tulud Cruz (May 14, 2003). "Bhikkhunis: Ordaining Buddhist Women". National Catholic Reporter. Archived from the original on 2015-03-30. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

She had to be ordained in Colombo, Sri Lanka...

- David N. Snyder. "Who's Who in Buddhism". Archived from the original on 2009-01-11. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- Ekachai, Sanitsuda (2019-04-29). "Perpetuating sexism through prayers" (Opinion). Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

Further reading

- Buswell, Robert E., ed. (2004). "Thailand", in Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 830–836. ISBN 0-02-865718-7.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Jerryson, Michael K. (2012). Buddhist Fury: Religion and Violence in Southern Thailand. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979329-7.

- Kabilsingh, Chatsumarn (1991). Thai Women in Buddhism. Parallax Press. ISBN 0-938077-84-8.

- Tambiah, Stanley (1970). Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in North-East Thailand. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09958-7.

- McCargo, D (2009). Thai Buddhism, Thai Buddhists and the southern conflict, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40 (1), 1-10

- Terwiel, B.J. (May 1976). "A Model for the Study of Thai Buddhism". Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (3): 391–403. doi:10.2307/2053271. JSTOR 2053271.

- Na-rangsi, Sunthorn (2002). "Administration of the Thai Sangha" (PDF). The Chulalongkorn Journal of Buddhist Studies. 1 (2): 59–74. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2012.