Schools of Buddhism

The schools of Buddhism are the various institutional and doctrinal divisions of Buddhism that have existed from ancient times up to the present. The classification and nature of various doctrinal, philosophical or cultural facets of the schools of Buddhism is vague and has been interpreted in many different ways, often due to the sheer number (perhaps thousands) of different sects, subsects, movements, etc. that have made up or currently make up the whole of Buddhist traditions. The sectarian and conceptual divisions of Buddhist thought are part of the modern framework of Buddhist studies, as well as comparative religion in Asia.

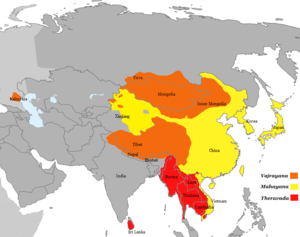

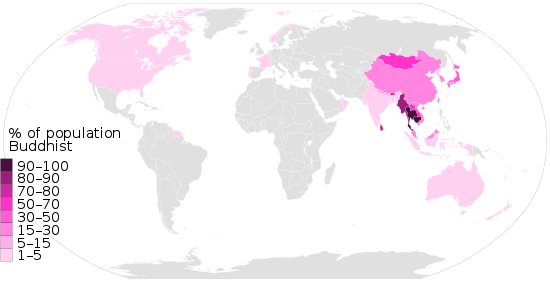

From a largely English-language standpoint, and to some extent in most of Western academia, Buddhism is separated into two groups: Theravāda, literally "the Teaching of the Elders" or "the Ancient Teaching," and Mahāyāna, literally the "Great Vehicle." The most common classification among scholars is threefold: Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna.

Classifications

In contemporary Buddhist studies, modern Buddhism is often divided into three major branches, traditions or categories:[1][2][3][4]

- Theravāda ("Teaching of the Elders"), also called "Southern Buddhism", mainly dominant in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. This tradition generally focuses on the study of its main textual collection, the Pali Canon as well other forms of Pali literature. The Pali language is thus its lingua franca and sacred language. This tradition is sometimes denominated as a part of Nikaya Buddhism, referring to the conservative Buddhist traditions in India who did not accept the Mahāyāna sutras into their Tripitaka collection of scriptures. It is also sometimes seen as the only surviving school out of the Early Buddhist schools, being derived from the Sthavira Nikāya via the Sri Lankan Mahavihara tradition.

- East Asian Mahāyāna ("Great Vehicle"), East Asian Buddhism or "Eastern Buddhism", prominent in East Asia and derived from the Chinese Buddhist traditions which began to develop during the Han Dynasty. This tradition focuses on the teachings found in Mahāyāna sutras (which are not considered canonical or authoritative in Theravāda), preserved in the Chinese Buddhist Canon, in the classical Chinese language. There are many schools and traditions, with different texts and focuses, such as Zen (Chan) and Pure Land (see below).

- Vajrayāna ("Vajra Vehicle"), also known as Mantrayāna, Tantric Buddhism and Esoteric Buddhism. This category is mostly represented in "Northern Buddhism", also called "Indo-Tibetan Buddhism" (or just "Tibetan Buddhism"), but also overlaps with certain forms of East Asian Buddhism (see: Shingon). It is prominent in Tibet, Bhutan and the Himalayan region as well as in Mongolia and the Russian republic of Kalmykia. It is sometimes considered to be a part of the broader category of Mahāyāna Buddhism instead of a separate tradition. The main texts of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism are contained in the Kanjur and the Tenjur. Besides the study of major Mahāyāna texts, this branch emphasizes the study of Buddhist tantric materials, mainly those related to the Buddhist tantras.

A fourth branch is sometimes included as well:

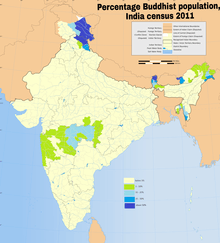

- Navayāna ("new vehicle"), also called "Bhimayana", "Neo Buddhism" or "Ambedkarite Buddhism", mainly dominant in Maharashtra, India. It refers to the re-interpretation of Buddhism by B. R. Ambedkar.[5][6] Ambedkar was born in a Dalit (untouchable) family during the colonial era of India, studied abroad, became a Dalit leader, and announced in 1935 his intent to convert from Hinduism to Buddhism.[7] Thereafter Ambedkar studied texts of Buddhism, found several of its core beliefs and doctrines such as Four Noble Truths and "non-self" as flawed and pessimistic, re-interpreted these into what he called "new vehicle" of Buddhism.[8][8] Ambedkar held a press conference on October 13, 1956, announcing his rejection of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, as well as of Hinduism.[9][10] Thereafter, he left Hinduism and adopted Navayana, about six weeks before his death.[5][8][9] In the Dalit Buddhist movement of India, Navayana is considered a new branch of Buddhism, different from the traditionally recognized branches of Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana. Marathi Buddhists follow Navayana.

Another way of classifying the different forms of Buddhism is through the different monastic ordination traditions. There are three main traditions of monastic law (Vinaya) each corresponding to the first three categories outlined above:

- Theravāda Vinaya

- Dharmaguptaka Vinaya (East Asian Mahayana)

- Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya (Tibetan Buddhism)

Terminology

The terminology for the major divisions of Buddhism can be confusing, as Buddhism is variously divided by scholars and practitioners according to geographic, historical, and philosophical criteria, with different terms often being used in different contexts. The following terms may be encountered in descriptions of the major Buddhist divisions:

- "Conservative Buddhism"

- an alternative name for the early Buddhist schools.

- "Early Buddhist schools"

- the schools into which Buddhism became divided in its first few centuries; only one of these survives as an independent school, Theravāda

- "East Asian Buddhism"

- a term used by scholars[11] to cover the Buddhist traditions of Japan, Korea, and most of China and Southeast Asia

- "Eastern Buddhism"

- an alternative name used by some scholars[12] for East Asian Buddhism; also sometimes used to refer to all traditional forms of Buddhism, as distinct from Western(ized) forms.

- "Ekayāna (one yana)

- Mahayana texts such as the Lotus Sutra and the Avatamsaka Sutra sought to unite all the different teachings into a single great way. These texts serve as the inspiration for using the term Ekayāna in the sense of "one vehicle". This "one vehicle" became a key aspect of the doctrines and practices of Tiantai and Tendai Buddhist sects, which subsequently influenced Chán and Zen doctrines and practices. In Japan, the one-vehicle teaching of the Lotus Sutra also inspired the formation of the Nichiren sect.

- "Esoteric Buddhism"

- usually considered synonymous with "Vajrayāna".[13] Some scholars have applied the term to certain practices found within the Theravāda, particularly in Cambodia.[14]

- "Hīnayāna"

- literally meaning "lesser vehicle." It is considered a controversial term when applied by the Mahāyāna to mistakenly refer to the Theravāda school, and as such is widely viewed as condescending and pejorative.[15] Moreover, Hīnayāna refers to the now non extant schools with limited set of views, practices and results, prior to the development of the Mahāyāna traditions. The term is currently most often used as a way of describing a stage on the path in Tibetan Buddhism, but is often mistakenly confused with the contemporary Theravāda tradition, which is far more complex, diversified and profound, than the literal and limiting definition attributed to Hīnayāna .[16] Its use in scholarly publications is now also considered controversial.[17]

- "Lamaism"

- an old term, still sometimes used, synonymous with Tibetan Buddhism; widely considered derogatory.

- "Mahāyāna"

- a movement that emerged from early Buddhist schools, together with its later descendants, East Asian and Tibetan Buddhism. Vajrayāna traditions are sometimes listed separately. The main use of the term in East Asian and Tibetan traditions is in reference to spiritual levels,[18] regardless of school.

- "Mainstream Buddhism"

- a term used by some scholars for the early Buddhist schools.

- "Mantrayāna"

- usually considered synonymous with "Vajrayāna".[19] The Tendai school in Japan has been described as influenced by Mantrayana.[18]

- "Navayāna"

- ("new vehicle") refers to the re-interpretation of Buddhism by modern Indian jurist and social reformer B. R. Ambedkar.[5][6]

- "Newar Buddhism"

- a non-monastic, caste based Buddhism with patrilineal descent and Sanskrit texts.

- "Nikāya Buddhism" or "schools"

- an alternative term for the early Buddhist schools.

- "Non-Mahāyāna"

- an alternative term for the early Buddhist schools.

- "Northern Buddhism"

- an alternative term used by some scholars[12] for Tibetan Buddhism. Also, an older term still sometimes used to encompass both East Asian and Tibetan traditions. It has even been used to refer to East Asian Buddhism alone, without Tibetan Buddhism.

- "Secret Mantra"

- an alternative rendering of Mantrayāna, a more literal translation of the term used by schools in Tibetan Buddhism when referring to themselves.[20]

- "Sectarian Buddhism"

- an alternative name for the early Buddhist schools.

- "Southeast Asian Buddhism"

- an alternative name used by some scholars[21] for Theravāda.

- "Southern Buddhism"

- an alternative name used by some scholars[12] for Theravāda.

- "Śravakayāna"

- an alternative term sometimes used for the early Buddhist schools.

- "Tantrayāna" or "Tantric Buddhism"

- usually considered synonymous with "Vajrayāna".[19] However, one scholar describes the tantra divisions of some editions of the Tibetan scriptures as including Śravakayāna, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna texts[22] (see Buddhist texts). Some scholars[23], particularly François Bizot,[24] have used the term "Tantric Theravada" to refer to certain practices found particularly in Cambodia.

- "Theravāda"

- the Buddhism of Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and parts of Vietnam, China, India, and Malaysia. It is the only surviving representative of the historical early Buddhist schools. The term "Theravāda" is also sometimes used to refer to all the early Buddhist schools.[25]

- "Tibetan Buddhism"

- usually understood as including the Buddhism of Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan and parts of China, India and Russia, which follow the Tibetan tradition.

- "Vajrayāna"

- a movement that developed out of Indian Mahāyāna, together with its later descendants. There is some disagreement on exactly which traditions fall into this category. Tibetan Buddhism is universally recognized as falling under this heading; many also include the Japanese Shingon school. Some scholars[26] also apply the term to the Korean milgyo tradition, which is not a separate school. One scholar says, "Despite the efforts of generations of Buddhist thinkers, it remains exceedingly difficult to identify precisely what it is that sets the Vajrayana apart."[27]

Early schools

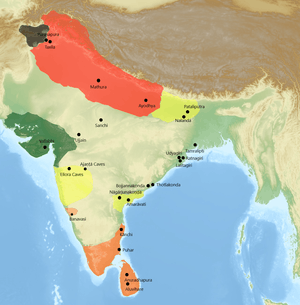

* Red: non-Pudgalavāda Sarvāstivāda school

* Orange: non-Dharmaguptaka Vibhajyavāda schools

* Yellow: Mahāsāṃghika

* Green: Pudgalavāda (Green)

* Gray: Dharmaguptaka

Note the red and grey schools already gave some original ideas of Mahayana Buddhism and the Sri Lankan section (see Tamrashatiya) of the orange school is the origin of modern Theravada Buddhism.

The early Buddhist schools or mainstream sects refers to the sects into which the Indian Buddhist monastic saṅgha split. They are also called the Nikaya Buddhist schools, and in Mahayana Buddhism they are referred to either as the Śrāvaka (disciple) schools or Hinayana (inferior) schools.

Most scholars now believe that the first schism was originally caused by differences in vinaya (monastic rule).[28] Later splits were also due to doctrinal differences and geographical separation.

The first schism separated the community into two groups, the Sthavira (Elders) Nikaya and the Mahāsāṃghika (Great Community). Most scholars hold that this probably occurred after the time of Ashoka.[29] Out of these two main groups later arose many other sects or schools.

From the Sthaviras arose the Sarvāstivāda sects, the Vibhajyavādins, the Theravadins, the Dharmaguptakas and the Pudgalavāda sects.

The Sarvāstivāda school, popular in northwest India and Kashmir, focused on Abhidharma teachings.[30] Their name means "the theory that all exists" which refers to one of their main doctrines, the view that all dharmas exist in the past, present and in the future. This is an eternalist theory of time.[31] Over time, the Sarvāstivādins became divided into various traditions, mainly the Vaibhāṣika (who defended the orthodox "all exists" doctrine in their Abhidharma compendium called the Mahāvibhāṣa Śāstra), the Sautrāntika (who rejected the Vaibhāṣika orthodoxy) and the Mūlasarvāstivāda.

The Pudgalavāda sects (also known as Vātsīputrīyas) were another group of Sthaviras which were known for their unique doctrine of the pudgala (person). Their tradition was founded by the elder Vātsīputra circa 3rd century BCE.[32]

The Vibhajyavādins were conservative Sthaviras who did not accept the doctrines of either the Sarvāstivāda or the Pudgalavāda. In Sri Lanka, a group of them became known as Theravada, the only one of these sects that survives to the present day. Another sect which arose from the Vibhajyavādins were the Dharmaguptakas. This school was influential in spreading Buddhism to Central Asia and to China. Their Vinaya is still used in East Asian Buddhism.

The Mahāsāṃghikas also split into various sub groups. One of these were the Lokottaravādins (Transcendentalists), so called because of their doctrine which saw every action of the Buddha, even mundane ones like eating, as being of a supramundane and transcendental nature. One of the few Mahāsāṃghika texts which survive, the Mahāvastu, is from this school. Another sub-sect which emerged from the Mahāsāṃghika was called the Caitika. They were concentrated in Andhra Pradesh and in South India. Some scholars such as A.K. Warder hold that many important Mahayana sutras originated among these groups.[33] Another Mahāsāṃghika sect was named Prajñaptivāda. They were known for the doctrine that viewed all conditioned phenomena as being mere concepts (Skt. prajñapti).[34]

According to the Indian philosopher Paramartha, a further split among the Mahāsāṃghika occurred with the arrival of the Mahayana sutras. Some sub-schools, such as the Kukkuṭikas, did not accept the Mahayana sutras as being word of the Buddha, whole others, like the Lokottaravādins, did accept them.[35]

Theravāda

Theravāda is the only extant mainstream or non-Mahayana school. They are derived from the Sri Lankan Mahāvihāra sect, which was a branch of the South Indian Vibhajjavādins. Theravāda bases its doctrine on the Pāli Canon, the only complete Buddhist canon surviving in a classical Indian language. This language is Pāli, which serves as the school's sacred language and lingua franca.[36]

The different sects and groups in Theravāda often emphasize different aspects (or parts) of the Pāli canon and the later commentaries (especially the very influential Visuddhimagga), or differ in the focus on and recommended way of practice. There are also significant differences in strictness or interpretation of the vinaya.

The various divisions in Theravāda include:

- Bangladesh:

- Cambodia

- Myanmar:

- Thudhamma Nikaya

- Vipassanā tradition of Mahasi Sayadaw and disciples

- Shwegyin Nikaya

- Dvaya Nikaya or Dvara Nikaya (see Mendelson, Sangha and State in Burma, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 1975)

- Hngettwin Nikaya

- Thudhamma Nikaya

- Nepalese Theravāda

- Dharmodaya Sabha

- Sri Lankan Theravāda:

- Siam Nikaya

- Waturawila (or Mahavihara Vamshika Shyamopali Vanavasa Nikaya)

- Amarapura Nikaya

- Kanduboda (or Swejin Nikaya)

- Tapovana (or Kalyanavamsa)

- Ramañña Nikaya

- Sri Kalyani Yogasrama Samstha (or ‘Galduwa Tradition’)

- Delduwa

- Siam Nikaya

- Laotian Theravāda

- Thailand

- Maha Nikaya

- Dhammakaya Movement

- Mahasati meditation (mindfulness meditation)

- Thammayut Nikaya

- Thai Forest Tradition, focused on monastic living in the wilderness

- Santi Asoke, a recent reform movement

- Maha Nikaya

- Vietnamese Theravāda

- Vipassana movement, a strongly lay focused meditation based movement, popular in the West (where it is also known as "Insight Meditation")

- Tantric Theravada, includes many esoteric elements not present in classic Theravāda

Mahāyāna schools

Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism

Mahāyāna (Great Vehicle) Buddhism is category of traditions which focus on the bodhisattva path and affirm texts known as Mahāyāna sutras. These texts are seen by modern scholars as dating as far back as the 1st century BCE.[37] Unlike Theravada and other early schools, Mahāyāna schools generally hold that there are currently many Buddhas which are accessible, and that they are transcendental or supramundane beings.[38]

In India, there were two major traditions of Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy. The earliest was the Mādhyamaka ("Middle Way"), also known as Śūnyavāda, the emptiness school. This tradition followed the works of the philosopher Nāgārjuna (c. 150 – c. 250 CE). The other major school was Yogācāra ("yoga practice") school, also known as Vijñānavāda (the doctrine of consciousness), Vijñaptivāda (the doctrine of ideas or percepts).

Some scholars also note that the Tathāgatagarbha texts constitute a third "school" of Indian Mahāyāna.[39]

East Asian Mahayana

East Asian Buddhism or East Asian Mahayana refers to the schools that developed in East Asia and use the Chinese Buddhist canon. It is a major religion in China, Japan, Vietnam, Korea, Malaysia and Singapore. East Asian Buddhists constitute the numerically largest body of Buddhist traditions in the world, numbering over half of the world's Buddhists.[40][41]

East Asian Mahayana began to develop in China during the Han dynasty (when Buddhism was first introduced from Central Asia). It is thus influenced by Chinese culture and philosophy.[42] East Asian Mahayana developed new, uniquely Asian interpretations of Buddhist texts and focused on the study of Mahayana sutras.[43]

East Asian Buddhist monastics generally follow the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya.[44]

Main sects

- Chinese Buddhism (Buddhism in contemporary China is characterized by institutional fluidity between schools) [45]

- Jingtu (Pure Land)

- Guanyin Buddhism

- Lüzong [46] (Vinaya school)

- Chengshi (Satyasiddhi- historical)

- Kosa (Abhidharmakośa- historical)

- Sanlun (Mādhyamaka)

- Weishi (Yogācāra)

- Niepan (Nirvana- historical)

- Dilun (Daśabhūmikā- absorbed into Huayan)

- Tiantai

- Huayan

- Chan (Zen)

- Sanjiejiao (historical)

- Oxhead school (historical)

- East Mountain Teaching (historical)

- Heze school (historical)

- Hongzhou school (historical)

- Caodong school

- Fayan school (absorbed into Linji school)

- Yunmen school (absorbed into Linji school)

- Tibetan Chan (historical)

- Zhenyan (Esoteric)

- Humanistic Buddhism

- Vietnamese Buddhism (Traditions are generally syncretized in Vietnam, rather than existing as distinct schools)

- Tịnh Độ (Pure Land)

- Thiên Thai (Tiantai)

- Hoa Nghiêm (Huayen)

- Thiền (Zen)

- Lâm Tế (Linji school)

- Tào Động (Caodong school)

- Trúc Lâm (Syncretized with Taoism and Confucianism)

- Plum Village Tradition (Engaged Buddhism)

- Đạo Bửu Sơn Kỳ Hương (Millenarian movement)

- Hòa Hảo (Reformist movement)

- Korean Buddhism

- Tongbulgyo (Interpenetrated Buddhism – including Jeongto, or Pure Land)

- Gyeyul (Vinaya school- historical)

- Samnon (Mādhyamaka- historical)

- Beopsang (Yogācāra- historical)

- Yeolban (Nirvana- historical)

- Wonyung (Avatamsaka- historical)

- Cheontae (Tiantai)

- Hwaeom (Huayen- absorbed into Jogye Order)

- Seon (Zen)

- Wonbulgyo (Korean Reformed Buddhism)

- Jingak Order (Shingon syncretized with Humanistic Buddhism)

- Japanese Buddhism

- Pure Land

- Risshū (Vinaya school)

- Jojitsu (Satyasiddhi – historical)

- Kusha (Abhidharmakośa – historical)

- Sanron (Mādhyamaka – historical)

- Hossō (Yogācāra)

- Kegon (Huayen syncretized with Shingon)

- Mikkyō (Esoteric)

- Tendai (Tiantai syncretized with Zhenyan, Lüzong and Oxhead school)

- Shingon (Zhenyan)

- Kōyasan Shingon-shū

- Shingon Risshu (Syncretized with Risshū)

- Shingon-shu Buzan-ha

- Shingon-shū Chizan-ha

- Shinnyo-en

- Shugendo (Syncretized with Shinto, Taoism and Onmyōdō)

- Zen (Chan)

- Rinzai (Linji school)

- Fuke-shū (Historical)

- Sōtō (Caodong school)

- Ōbaku (Linji school syncretized with Jingtu)

- Sanbo Kyodan (Sōtō syncretized with Rinzai)

- Rinzai (Linji school)

- Nichiren Buddhism

- Nichiren Shū

- Honmon Butsuryū-shū

- Kempon Hokke

- Nichiren Shōshū

Esoteric schools

_-_(multiple_figures)18th_century_Boston_MFA.jpg)

Esoteric Buddhism, also known as Vajrayāna, Mantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, and Tantric Buddhism is often placed in a separate category by scholars due to its unique tantric features and elements. Esoteric Buddhism arose and developed in medieval India among esoteric adepts known as Mahāsiddhas. Esoteric Buddhism maintains its own set of texts alongside the classic scriptures, these esoteric works are known as the Buddhist Tantras. It includes practices that make use of mantras, dharanis, mudras, mandalas and the visualization of deities and Buddhas.

Main Esoteric Buddhist traditions include:

- Indian Esoteric Buddhism (Historical)

- Ari Buddhism (Historical)

- Tantric Theravada

- Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism

- Philippine Esoteric Buddhism

- Azhaliism

- Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, the most widespread of these traditions, is practiced in Tibet, parts of North India, Nepal, Bhutan, China and Mongolia.

- Nyingma

- Bön (Indigenous, often considered "pre-Buddhist” in origin)

- Kadam (Historical)

- Sakya

- Bodong

- Jonang

- Kagyu

- Gelug

- Tibetan Pure Land

- Rimé movement (Non-sectarian)

- New Kadampa Tradition

- Kalmyk Buddhism

- Buryat Buddhism

- Tuvan Buddhism

- Mongolian Buddhism

- Bhutanese Buddhism

- Newar Buddhism (Nepal)

- Chinese Esoteric Buddhism (zhenyan, 真言)

- Korean Esoteric Buddhism (milgyo, 密教)

- Jingak Order (Shingon syncretized with Humanistic Buddhism)

- Japanese Mikkyo

New Buddhist movements

Various Buddhist new religious movements arose in the 20th century, including the following.

- Aum Shinrikyo

- Buddhist feminism

- Buddhist modernism

- Buddhist socialism

- Coconut Religion

- Dalit Buddhist movement, also known as Navayana and Ambedkarite Buddhism

- Dhammakaya Movement

- Diamond Way

- Engaged Buddhism

- Falun Gong

- Forshang Buddhism World Center

- Gedatsukai

- Guanyin Famen

- Hòa Hảo

- Ho No Hana

- Humanistic Buddhism

- Jingak Order

- Juniper Foundation

- Kenshōkai

- Kokuchūkai

- Kwan Um School of Zen

- New Kadampa Tradition

- Nipponzan Myōhōji

- PL Kyodan

- Reiyūkai

- Rulaizong

- Sanbo Kyodan

- Secular Buddhism

- Shambhala Buddhism

- Share International

- Shinnyo-en

- Shōshinkai

- Sōka Gakkai

- Thai Forest Tradition

- Tibbetibaba

- Triratna Buddhist Community

- True Buddha School

- Vipassana movement

- Western Buddhism

- Won Buddhism

See also

References

- Lee Worth Bailey, Emily Taitz (2005), Introduction to the World's Major Religions: Buddhism, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 67.

- Mitchell, Scott A. (2016), Buddhism in America: Global Religion, Local Contexts, Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 87.

- Gethin, Rupert, The Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press, pp. 253–266.

- William H. Swatos (ed.) (1998) Encyclopedia of Religion and Society, Altamira Press, p. 66.

- Gary Tartakov (2003). Rowena Robinson (ed.). Religious Conversion in India: Modes, Motivations, and Meanings. Oxford University Press. pp. 192–213. ISBN 978-0-19-566329-7.

- Christopher Queen (2015). Steven M. Emmanuel (ed.). A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 524–525. ISBN 978-1-119-14466-3.

- Nicholas B. Dirks (2011). Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India. Princeton University Press. pp. 267–274. ISBN 978-1-4008-4094-6.

- Eleanor Zelliot (2015). Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India. Taylor & Francis. pp. 13, 361–370. ISBN 978-1-317-40357-9.

- Christopher Queen (2015). Steven M. Emmanuel (ed.). A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 524–529. ISBN 978-1-119-14466-3.

- Skaria, A (2015). "Ambedkar, Marx and the Buddhist Question". Journal of South Asian Studies. Taylor & Francis. 38 (3): 450–452. doi:10.1080/00856401.2015.1049726., Quote: "Here [Navayana Buddhism] there is not only a criticism of religion (most of all, Hinduism, but also prior traditions of Buddhism), but also of secularism, and that criticism is articulated moreover as a religion."

- B & G, Gethin, R & J, P & K

- Penguin, Harvey

- Encyclopedia of Religion, Macmillan, New York, volume 2, p. 440

- Indian Insights, Luzac, London, 1997

- "Hinayana (literally, 'inferior way') is a polemical term, which self-described Mahāyāna (literally, 'great way') Buddhist literature uses to denigrate its opponents", p. 840, MacMillan Library Reference Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 2004

- Ray, Reginald A (2000) Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism, p. 240

- "The supposed Mahayana-Hinayana dichotomy is so prevalent in Buddhist literature that it has yet fully to loosen its hold over scholarly representations of the religion", p. 840, MacMillan Library Reference Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 2004

- '

- Harvey, pp. 153ff

- Hopkins, Jeffrey (1985) The Ultimate Deity in Action Tantra and Jung's Warning against Identifying with the Deity Buddhist-Christian Studies, Vol. 5, (1985), pp. 159–172

- R & J, P & K

- Skilling, Mahasutras, volume II, Parts I & II, 1997, Pali Text Society, Lancaster, p. 78

- Indian Insights, loc. cit.

- Crosby, Kate( 2000)Tantric Theravada: A bibliographic essay on the writings of François Bizot and others on the yogvacara Tradition. In Contemporary Buddhism, 1:2, 141–198

- Encyclopedia of Religion, volume 2, Macmillan, New York, 1987, pp. 440ff; Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, sv Buddhism

- Harvey

- Lopez, Buddhism in Practice, Princeton University Press, 1995, p. 6

- Harvey, Peter (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–90.

- Cox, Collett (1995), Disputed Dharmas: Early Buddhist Theories on Existence, Tokyo: The Institute for Buddhist Studies, p. 23, ISBN 4-906267-36-X

- Westerhoff, Jan (2018). "The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy in the First Millennium CE", pp. 60 – 61.

- Kalupahana, David; "A history of Buddhist philosophy, continuities and discontinuities", p. 128.

- Williams, Paul (2005), "Buddhism: The early Buddhist schools and doctrinal history; Theravāda doctrine," Volume 2, Taylor & Francis, p. 86.

- Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 313

- Harris, Ian Charles (1991). The Continuity of Madhyamaka and Yogacara in Indian Mahayana Buddhism. p. 98

- Sree Padma. Barber (2008), Anthony W. Buddhism in the Krishna River Valley of Andhra, p. 68.

- Crosby, Kate (2013), Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity, p. 2.

- Warder, A.K. (3rd edn. 1999). Indian Buddhism: p. 335.

- Williams, Paul, Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations, Routledge, 2008, p. 21.

- Kiyota, M. (1985). Tathāgatagarbha Thought: A Basis of Buddhist Devotionalism in East Asia. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 207–231.

- Pew Research Center, Global Religious Landscape: Buddhists.

- Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J. (2013). The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography (PDF). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 34. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Gethin, Rupert, The Foundations of Buddhism, OUP Oxford, 1998, p. 257.

- Williams, pAUL, Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations, Taylor & Francis, 2008, P. 129.

- Gethin, Rupert, The Foundations of Buddhism, OUP Oxford, 1998, p. 260

- "Buddhism in China Today: An Adaptable Present, a Hopeful Future". Retrieved 2020-06-01..

- "法鼓山聖嚴法師數位典藏". Archived from the original on 2013-05-28. Retrieved 2013-07-29..

Further reading

- Bhikkhu Sujato (2007). Sects and sectarianism: the origins of Buddhist schools, Taipei, Taiwan: Buddha Educational Foundation; revised edidion: Santipada 2012

- Dutt, N. (1998). Buddhist Sects in India. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Coleman, Graham, ed. (1993). A Handbook of Tibetan Culture. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.. ISBN 1-57062-002-4.

- Warder, A.K. (1970). Indian Buddhism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

External links

- The Sects of the Buddhists by T. W. Rhys Davids, in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1891. pp. 409–422