Mahayana sutras

The Mahayana sutras are a broad genre of Buddhist scriptures that various traditions of Mahayana Buddhism accept as canonical. They are largely preserved in the Chinese Buddhist canon, the Tibetan Buddhist canon, and in extant Sanskrit manuscripts. Around one hundred Mahayana sutras survive in Sanskrit, or in Chinese and Tibetan translations.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Transmission |

|

Teachings

|

|

Mahāyāna sūtras |

Mahayana Buddhists typically consider the Mahayana sutras to have been taught by Gautama Buddha, committed to memory and recited by his disciples, in particular Ananda, which were viewed as a substitute for the actual speech of the Buddha following his parinirvana (death).[2] This claim is based on oral tradition rather than on historical evidence.

History and background

Origins and early history

The origins of the Mahayana are not completely understood.[3] The earliest views of Mahayana Buddhism in the West assumed that it existed as a separate school in competition with the Theravada schools. Due to the veneration of buddhas and bodhisattvas, Mahayana was often interpreted as a more devotional, lay-inspired form of Buddhism, with supposed origins in stūpa veneration[4] or by making parallels with the Reformation. These views have been largely dismissed in modern times in light of a much broader range of early texts that are now available.[5] These earliest Mahayana texts often depict strict adherence to the path of a bodhisattva, and engagement in the ascetic ideal of a monastic life in the wilderness, akin to the ideas expressed in the Rhinoceros Sutra.[6] The old views of Mahayana as a separate lay-inspired and devotional sect are now largely dismissed as misguided and wrong on all counts.[7] The early versions of Mahayana sutras were not written documents but orally preserved teachings.[8][9] The verses which were committed to memory and recited by monks were viewed as the substitute for the actual speaking presence of the Buddha.[10]

The earliest textual evidence of the Mahayana comes from sutras originating around the beginning of the common era. Jan Nattier has noted that in some of the earliest Mahayana texts such as the Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra use the term "Mahayana", yet there is no doctrinal difference between Mahayana in this context and the early schools, and that "Mahayana" referred rather to the rigorous emulation of Gautama Buddha in the path of a bodhisattva seeking to become a fully enlightened buddha.[11]

There is also no evidence that Mahayana ever referred to a separate formal school or sect of Buddhism, but rather that it existed as a certain set of ideals, and later doctrines, for bodhisattvas.[12] Paul Williams has also noted that the Mahayana never had nor ever attempted to have a separate Vinaya or ordination lineage from the early Buddhist schools and therefore each bhikṣu or bhikṣuṇī adhering to the Mahayana formally belonged to an early school. This continues today with the Dharmaguptaka ordination lineage in East Asia and the Mūlasarvāstivāda ordination lineage in Tibetan Buddhism. Therefore, Mahayana was never a separate rival sect of the early schools.[13]

The Chinese monk Yijing who visited India in the seventh century, distinguishes Mahayana from Hinayana as follows:

Both adopt one and the same Vinaya, and they have in common the prohibitions of the five offences, and also the practice of the Four Noble Truths. Those who venerate the bodhisattvas and read the Mahayana sutras are called the Mahayanists, while those who do not perform these are called the Hīnayānists.[14]

Much of the early extant evidence for the origins of Mahayana comes from early Chinese translations of Mahayana texts. These Mahayana teachings were first propagated into China by Lokakṣema, the first translator of Mahayana sutras into Chinese during the second century.[15]

Scholarly views on dating

It cannot be determined by whom the Mahayana sutras were composed; many can only be dated firmly to the date when they were translated into another language.[16] Andrew Skilton summarizes a common prevailing view of the Mahayana sutras:

These texts are considered by Mahayana tradition to be buddhavacana, and therefore the legitimate word of the historical Buddha. The śrāvaka tradition, according to some Mahayana sutras themselves, rejected these texts as authentic buddhavacana, saying that they were merely inventions, the product of the religious imagination of the Mahayanist monks who were their fellows. Western scholarship does not go so far as to impugn the religious authority of Mahayana sutras, but it tends to assume that they are not the literal word of the historical Śākyamuni Buddha. Unlike the śrāvaka critics just cited, we have no possibility of knowing just who composed and compiled these texts, and for us, removed from the time of their authors by up to two millenia, they are effectively an anonymous literature. It is widely accepted that Mahayana sutras constitute a body of literature that began to appear from as early as the 1st century BCE, although the evidence for this date is circumstantial. The concrete evidence for dating any part of this literature is to be found in dated Chinese translations, amongst which we find a body of ten Mahayana sutras translated by Lokaksema before 186 C.E. – and these constitute our earliest objectively dated Mahayana texts. This picture may be qualified by the analysis of very early manuscripts recently coming out of Afghanistan, but for the meantime this is speculation. In effect we have a vast body of anonymous but relatively coherent literature, of which individual items can only be dated firmly when they were translated into another language at a known date.[16]

A. K. Warder notes that the Mahayana sutras are highly unlikely to have come from the teachings of the historical Buddha, since the language and style of every extant Mahāyāna sūtra is comparable more to later Indian texts than to texts that could have circulated in the Buddha's putative lifetime.[17] Warder also notes that the Tibetan historian Tāranātha (1575–1634) proclaimed that after the Buddha taught the sutras, they disappeared from the human world and circulated only in the world of the nagas; in Warder's view, “this is as good as an admission that no such texts existed until the 2nd century A.D.”[18]

John W. Pettit, while stating, "Mahayana has not got a strong historical claim for representing the explicit teachings of the historical Buddha", also argues that the basic concepts of Mahayana do occur in the Pāli Canon and that this suggests that Mahayana is "not simply an accretion of fabricated doctrines" but "has a strong connection with the teachings of Buddha himself".[19]

Mahayana has not got a strong historical claim for representing the explicit teachings of the historical Buddha; its scriptures evince a gradual development of doctrines over several hundred years. However, the basic concepts of Mahayana, such as the bodhisattva ethic, emptiness (sunyata), and the recognition of a distinction between buddhahood and arhatship as spiritual ideals, are known from the earliest sources available in the Pali canon. This suggests that Mahayana was not simply an accretion of fabricated doctrines, as it is sometimes accused of being, but has a strong connection with the teachings of Buddha himself.[19]

Others such as D. T. Suzuki have stated that it doesn't matter if the Mahayana sutras can be historically linked to the Buddha or not since Mahayana Buddhism is a living tradition and its teachings are followed by millions of people.[20]

However weak the claim to historicity that the Mahayana sutras hold, this does not mean that all scholars believe that the Pāli Canon is historical.[21][22][23]

Beliefs of Mahayana Buddhists

Some traditional accounts of the transmission of the Mahayana sutras claims that many parts were actually written down at the time of the Buddha and stored for five hundred years in the realm of the nāgas (serpent-like supernatural beings who dwell in another plane of being). The reason these accounts give for the late disclosure of the Mahayana teachings is that most people were initially unable to understand the Mahayana sutras at the time of the Buddha (500 BCE) and suitable recipients for these teachings had still to arise amongst humankind.[24]

According to Venerable Hsuan Hua from the tradition of Chinese Buddhism, there are five types of beings who may speak the sutras of Buddhism: a buddha, a disciple of a buddha, a deva, a ṛṣi, or an emanation of one of these beings; however, they must first receive certification from a buddha that its contents are true Dharma. Then these sutras may be properly regarded as the words of the Buddha (Skt. buddhavacana).[25]

Some teachers take the view that all teachings that stem from the fundamental insights of Buddha constitute the Buddha's speech, whether they are explicitly the historical words of the Buddha or not. There are scriptural supports for this perspective even in the Pāli Canon. There the Buddha is asked how the disciples should verify, after his death, which of the teachings circulating are his. In the Mahaparinibbana Sutta (DN 16) the Buddha is quoted as saying:

There is the case where a bhikkhu says this: 'In the Blessed One's presence have I heard this, in the Blessed One's presence have I received this: This is the Dhamma, this is the Vinaya, this is the Teacher's instruction.' His statement is neither to be approved nor scorned. Without approval or scorn, take careful note of his words and make them stand against the Suttas (discourses) and tally them against the Vinaya (monastic rules). If, on making them stand against the Suttas and tallying them against the Vinaya, you find that they don't stand with the Suttas or tally with the Vinaya, you may conclude: 'This is not the word of the Blessed One; this bhikkhu has misunderstood it' — and you should reject it. But if... they stand with the Suttas and tally with the Vinaya, you may conclude: 'This is the word of the Blessed One; this bhikkhu has understood it rightly.'"

The earliest extant Mahayana sutras

Some scholars have traditionally considered the earliest Mahayana sutras to include the very first versions of the Prajñāpāramitā series, along with texts concerning Akshobhya, which were probably composed in the 1st century BCE in the south of India.[26][27] Some early Mahayana sutras were translated by the Kushan monk Lokakṣema, who came to China from the kingdom of Gandhāra. His first translations to Chinese were made in the Eastern Han capital of Luoyang between 178 and 189 CE.[15] Some Mahayana sutras translated during the 2nd century CE include the following:[28]

- Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra

- Infinite Life Sutra

- Akṣobhyatathāgatasyavyūha Sūtra

- Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra

- Mañjuśrīparipṛcchā Sūtra

- Drumakinnararājaparipṛcchā Sūtra

- Śūraṅgama Samādhi Sūtra

- Bhadrapāla Sūtra

- Ajātaśatrukaukṛtyavinodana Sūtra

- Kāśyapaparivarta Sūtra

- Lokānuvartana Sūtra

- An early sutra connected to the Avatamsaka Sutra

Some of these were probably composed in the north of India in the 1st century CE.[29] Thus scholars generally think that the earliest Mahayana sutras were mainly composed in the south of India, and later the activity of writing additional scriptures was continued in the north.[30] However, the assumption that the presence of an evolving body of Mahayana scriptures implies the contemporaneous existence of distinct religious movement called Mahayana, which may be wrong.[31]

Teachings

The teachings as contained in the Mahayana sutras as a whole have been described as a loosely bound bundle of many teachings, which was able to contain the various contradictions between the varying teachings it comprises.[32] Because of these contradictory elements, there are "very few things that can be said with certainty about Mahayana Buddhism".[33][34]

Central to the Mahayana sutras is the ideal of the Bodhisattva path, something which is not unique to them however as such a path is also taught in non-Mahayana texts which also required prediction of future Buddhahood in the presence of a living Buddha.[35] What is unique to Mahayana sutras is the idea that the term bodhisattva is applicable to any person from the moment they intend to become a Buddha and without the requirement of a living Buddha.[35] They also claim that any person who accepts and uses Mahayana sutras either had already received or will soon receive such a prediction from a Buddha, establishing their position as an irreversible bodhisattva.[35]

The central practice advocated by the Mahayana sutras is focused around "the acquisition of merit, the universal currency of the Buddhist world, a vast quantity of which was believed to be necessary for the attainment of Buddhahood". The most important act for acquiring merit in these sutras is the listening, memorization, recitation, preaching, copying and worship of the Mahayana sutras themselves.[35]

Also, according to David Drewes other important features includes the practice of:

anumodanā, or “rejoicing,” in meritorious actions or the teachings of Mahayana sutras, typically combined with the dedication of the resulting merit either to the attainment of Buddhahood or to all beings.[35]

Mahayana sutras also expound on the importance of the six perfections (paramitas) as part of the path to Buddhahood, and special attention is given to the perfection of wisdom (prajnaparamita) which is seen as primary.[36]

Another innovative "shortcut" to Buddhahood in Mahayana sutras are what are often called Pure Land practices. These involve the invocation of Buddhas such as Amitabha and Aksobhya, who are said to have created "Buddha fields" or "pure lands" especially so that those beings who wish to be reborn there can easily and quickly become Buddhas. Reciting the Mahayana sutras and also simply the names of these Buddhas can allow one to be reborn in these places.[35]

Collections of Mahayana sutras

Bodhisattvapiṭaka

In the 4th century Mahayana abhidharma work Abhidharmasamuccaya, Asaṅga refers to the collection which contains the āgamas as the Śrāvakapiṭaka, and associates it with the śrāvakas and pratyekabuddhas.[37] Asaṅga classifies the Mahayana sutras as belonging to the Bodhisattvapiṭaka, which is designated as the collection of teachings for bodhisattvas.[37]

Modern canons

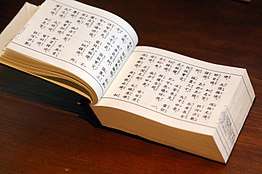

The Mahayana sutras survive predominantly in primary translations in Chinese and Tibetan from original texts in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit or various prakrits.

Although there is no definitive Mahayana canon as such, the printed or manuscript collections in Chinese and Tibetan, published through the ages, have preserved the majority of known Mahayana sutras. Many parallel translations of certain sutras exist. A handful of them, such as the Prajñāpāramitā sutras like the Heart Sutra and the Diamond Sutra, are considered fundamental by most Mahayana traditions.

The standard modern edition of the Buddhist Chinese canon is the Taisho Tripitaka, redacted during the 1920s in Japan, consisting of eighty-five volumes of writings that, in addition to numerous Mahayana texts, both canonical and not, also include Āgama collections, several versions of the vinaya, abhidharma and tantric writings. The first thirty-two volumes contain works of Indic origin, volumes thirty-three to fifty-five contain works of native Chinese origin and volumes fifty-six to eighty-four contain works of Japanese composition. The eighty-fifth volume contains miscellaneous items including works found at Dunhuang. A number of apocryphal sutras composed in China are also included in the Chinese Buddhist canon, although the spurious nature of many more was recognized, thus preventing their inclusion in the canon. The Sanskrit originals of many Mahayana texts have not survived to this day, although Sanskrit versions of the majority of the major Mahayana sutras have survived.

Brief descriptions of some sutras

Proto-Mahayana sutras

Early in the 20th century, a cache of texts was found in a mound near Gilgit. Amongst them was the Ajitasena Sūtra. This sutra appears to be a mixture of Mahayana and pre-Mahayana ideas. The text is set in a world where monasticism is the norm, typical of the Pāli Suttas; there is none of the usual antagonism towards the śravakas (i.e., the early Buddhists) or the notion of Arahantship, as is typical of Mahayana sutras such as the Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa Sūtra.

The Salistamba Sutra (rice stalk or rice sapling sūtra) has been considered as one of the first Mahayana sutras.[38] According to N. Ross Reat, this sutra has many parallels with the material in the Pali suttas (especially the Mahatanha-sahkhaya Sutta, M1:256-71), and could date as far back as 200 BCE.[39] It is possible that this sutra represents a period of Buddhist literature before the Mahayana had diverged significantly from the doctrine of the Early Buddhist schools.[40]

Samādhi sutras

Amongst the earliest Mahayana texts, the samādhi sutras are a collection of sutras that focus on the attainment of profound states of consciousness reached in meditation, perhaps suggesting that meditation played an important role in early Mahayana. These include the Pratyutpanna-sūtra, Samādhirāja-sūtra and Śūraṅgama-samādhi-sūtra.

Perfection of Wisdom texts

These deal with Buddhist wisdom (prajñā). "Wisdom" in this context means the ability to see reality as it truly is. They do not contain an elaborate philosophical argument, but simply try to point to the true nature of reality, especially through the use of paradox. The basic premise is a radical non-dualism, in which every and any dichotomist way of seeing things is denied: so phenomena are neither existent, nor non-existent, but are marked by emptiness (śūnyatā), an absence of any essential, unchanging nature. The Perfection of Wisdom in One Letter illustrates this approach by choosing to represent the perfection of wisdom with the Sanskrit and Pāli short a or "schwa" vowel ("अ", [ə]). As a prefix, this negates a word's meaning, e.g., changing "svabhāva", "with essence" to "asvabhāva", "without essence".[41] It is the first letter of Indic alphabets and, as a sound on its own, can be seen as the most neutral and basic of speech sounds.[42]

Many sutras are known by the number of lines, or ślokas, that they contain.

Saddharma Puṇḍarīka

This sutra is called the Lotus Sutra, White Lotus Sutra, Sutra of the White Lotus or Sutra on the White Lotus of the Sublime Dharma; Sanskrit: Saddharma-pundarīka-sūtra; 妙法蓮華經 Cn: Miàofǎ Liánhuā Jīng; Jp: Myōhō Renge Kyō. Probably written down in the period 100 BCE – 150 CE, the Lotus Sutra proposes that the three yānas (śrāvakayāna, pratyekabuddhayāna and bodhisattvayāna) are not in fact three different paths leading to three goals, but one path, with one goal. This doctrine defines the enlightenment of a Buddha as the ultimative goal and the sutra predicts that all those who hear the Dharma will eventually achieve this goal. The earlier teachings are said to be skilful means to teach beings according to their capacities.[44][45] The sutra is notable for the (re)appearance of the Buddha Prabhutaratna, who had died several aeons earlier, because it suggests that a Buddha is not inaccessible after his parinirvāṇa and also that his life-span is said to be inconceivably long because of the accumulation of merit in past lives. This idea, though not necessarily from this source, forms the basis of the later doctrine of the three bodies (trikāya). Later it became associated particularly with the Tien Tai school in China (Tendai in Japan) and the Nichiren schools in Japan.

In some East Asian traditions, the Lotus Sūtra has been compiled together with two other sutras which serve as a prologue and epilogue, respectively the Innumerable Meanings Sutra and the Samantabhadra Meditation Sutra. This composite sutra is often called the Threefold Lotus Sūtra or Three-Part Dharma Flower Sutra.[46]

Pure Land sutras

The Pure Land teachings were first developed in India, and were very popular in Kashmir and Central Asia, where they may have originated.[47] Pure Land sutras were brought from the Gandhāra region to China as early as 147 CE, when the Kushan monk Lokakṣema began translating the first Buddhist sutras into Chinese.[48] The earliest of these translations show evidence of having been translated from the Gāndhārī language, a prakrit descended from Vedic Sanskrit, which was used in Northwest India.[49]

The Pure Land sutras are principally the Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, and the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra. The shorter sutra is also known as the Amitābha Sūtra, and the longer sutra is also known as the Infinite Life Sūtra. These sutras describe Amitābha and his Pure Land of Bliss, called Sukhāvatī. Also related to the Pure Land tradition is the Pratyutpanna Samādhi Sūtra, which describes the practice of reciting the name of Amitābha Buddha as a meditation method. In addition to these, many other Mahayana texts also feature Amitābha Buddha, and a total of 290 such works have been identified in the Taishō Tripiṭaka.[50]

Pure Land texts describe the origins and nature of the Western Pure Land in which the Buddha Amitabha resides. They list the forty-eight vows made by Amitabha as a bodhisattva by which he undertook to build a Pure Land where beings are able to practise the Dharma without difficulty or distraction. The sutras state that beings can be reborn there by pure conduct and by practices such as thinking continuously of Amitabha, praising him, recounting his virtues, and chanting his name. These Pure Land sutras and the practices they recommend became the foundations of Pure Land Buddhism, which focus on the salvific power of faith in the vows of Amitabha.

The Vimalakirti Nirdeśa Sūtra

In the Vimalakirti sutra, composed some time between the first and second century CE,[51] the bodhisattva Vimalakīrti appears as a layman to teach the Dharma. This is seen by some as a strong assertion of the value of lay practice.[52] The sutra teaches, among other subjects, the meaning of nondualism, the doctrine of the true body of the Buddha, the characteristically Mahāyāna claim that the appearances of the world are mere illusions, and the superiority of the Mahāyāna over other paths. It places in the mouth of the lay practitioner Vimalakīrti a teaching addressed to both arhats and bodhisattvas, regarding the doctrine of śūnyatā. In most versions, the discourse of the text culminates with a wordless teaching of silence.[53] This sutra has been very popular in China and Japan.[54]

Confession Sutras

The Triskandha Sūtra and the Golden Light Sutra (Suvarṇaprabhāsa-sūtra) focus on the practice of confession of faults. The Golden Light Sutra became especially influential in Japan, where its chapter on the universal sovereign was used by Japanese emperors to legitimise their rule and it provided a model for a well-run state.

The Avataṃsaka Sutra

This is large composite text consisting of several parts, most notably the Daśabhūmika Sutra and the Gandavyuha Sutra. It probably reached its current form by about the 4th century CE, although parts of it, such as those mentioned above, are thought to date from the 1st or 2nd century CE. The Gandavyuha Sutra is thought to be the source of a cult of Vairocana that later gave rise to the Mahāvairocana-abhisaṃbodhi tantra, which in turn became one of two central texts in Shingon Buddhism and is included in the Tibetan canon as a carya class tantra. The Avataṃsaka Sutra became the central text for the Hua-yen (Jp. Kegon) school of Buddhism, the most important doctrine of which is the interpenetration of all phenomena.

Third turning sutras

These sutras primarily teach the doctrine of Representation Only (vijñapti-mātra), associated with the Yogacara school. The Sandhinirmocana Sutra (c 2nd century CE) is the earliest surviving sutra in this class. It divides the teachings of the Buddha into three types, which it calls the "three turnings of the wheel of the Dharma." To the first turning, it ascribes the Āgamas of the śravakas, to the second turning the lower Mahayana sutras including the Prajñā-pāramitā sutras, and finally sutras like itself are deemed to comprise the third turning. Moreover, the first two turnings are considered to be provisional in this system of classification, while the third group is said to present the final truth without a need for further explication (nītārtha). The well-known Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, composed sometime around the 4th century CE, is sometimes included in this group, although it is somewhat syncretic in nature, combining pure Mahayana doctrines with those of the tathāgatagarbha system and was unknown or ignored by the progenitors of the Mahayana system. The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra was influential in Chan Buddhism.

Tathāgatagarbha class sutras

These are especially the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra, the Śrīmālā Sūtra (Śrīmālādevi-simhanāda Sūtra) and the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra (which is very different in character from the Pāli Mahaparinibbana Sutta).

Collected Sutras

These two large sutras are, again, actually collections of other sutras. The Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra contains 49 individual works, and the Mahāsamnipāta-sūtra is a collection of 17 shorter works. Both seem to have been finalised by about the 5th century, although some parts of them are considerably older.

Esoteric Sūtras

Esoteric sutras comprise an important category of works that are esoteric, in the sense that they are often devoted to a particular mantra or dhāraṇī. Well-known dhāraṇī texts include the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra and the Cundī Dhāraṇī Sūtra.

Transmigration sutras

A number of sutras focus on actions that lead to existence in the various spheres of existence, or expound the doctrine of the twelve links of dependent-origination (pratītyasamutpāda).

Discipline sutras

These focus on principles that guide the behaviour of bodhisattvas, and include the Kāshyapa-parivarta, the Bodhisattva-prātimokṣa Sutra, and the Brahmajāla Sutra. For monastics, the Bequeathed Teachings Sutra is a necessary manual that guides them through the life of cultivation.

Sutras devoted to individual figures

A large number of sutras describe the nature and virtues of a particular Buddha or bodhisattva and their pure land, including Mañjusri, Kṣitigarbha, the Buddha Akṣobhya, and Bhaiṣajyaguru, also known as the Medicine Buddha.

Vaipūlya Sūtras devoted to all Tathāgatas

The most widely used (in liturgy) of these is the Bhadra-kalpika Sutra, available in various languages (Chinese, Tibetan, Mongolian, etc.) in variants that differ slightly as to the number of Tathāgatas enumerated. For example, the Khotanese version is the proponent of a 1005-Tathāgata system. There is in use in the Shingon school a sutra naming some 10,000 Tathāgatas, distinguishing the ones longer-lived after enlightenment (the same as in the approximately 1,000 in the Bhadra-kalpika) as "Sun-Buddhas", and the shorter-lived ones as "Moon-Buddhas".

See also

Notes

- Skilton 1997, p. 101.

- McMahan 1998, p. 249.

- Hirakawa 1990, p. 260.

- Hirakawa 1990, p. 271.

- e.g. Williams, Mahayana Buddhism

- "As scholars have moved away from this limited corpus, and have begun to explore a wider range of Mahayana sutras, they have stumbled on, and have started to open up, a literature that is often stridently ascetic and heavily engaged in reinventing the forest ideal, an individualistic, antisocial, ascetic ideal that is encapsulated in the apparently resurrected image of “wandering alone like a rhinoceros.” Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004): p. 494

- "One of the most frequent assertions about the Mahayana is that it was a lay-influenced, or even lay-inspired and dominated, movement that arose in response to the increasingly closed, cold, and scholastic character of monastic Buddhism. This, however, now appears to be wrong on all counts...much of its [Hinayana's] program being in fact intended and designed to allow laymen and women and donors the opportunity and means to make religious merit." Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004): p. 494

- Apple, James B. (2014). "The Phrase dharmaparyāyo hastagato in Mahāyāna Buddhist Literature: Rethinking the Cult of the Book in Middle Period Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 134 (1): 27. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.134.1.0025. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.134.1.0025.

- Drewes, David (2015). "Oral Texts in Indian Mahayana". Indo-Iranian Journal. 58: 132–133. doi:10.1163/15728536-05800051.

Between the tremendous emphasis that Mahāyāna sūtras place on memorization and the central role that they attribute to dharmabhāṇakas, which I have discussed elsewhere(2011), Mahāyānists surely could have preserved their texts without writing.48 Though most Mahayana sutras undoubtedly would eventually have been lost without writing, this is a separate issue, and something that is also true of nikaya/agama sutras. Writing was not necessary for the Mahayana to emerge." and "Moriz Winternitz observed more than a century ago that the characteristic of repetition found in Pāli texts "is exaggerated to such a degree in the longer Prajñā-pāramitās that it would be quite possible to write down more than one half of a gigantic work like the Śatasāhasrikā-Prajñā-Pāramitā from memory(1927,2:322)."

- McMahan 1998.

- Nattier 2003, pp. 193-4.

- Nattier 2003, pp. 193-194.

- Williams, Paul (2008) Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations: p. 4-5

- Williams, Paul (2008) Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations: p. 5

- "The most important evidence — in fact the only evidence — for situating the emergence of the Mahayana around the beginning of the common era was not Indian evidence at all, but came from China. Already by the last quarter of the 2nd century CE, there was a small, seemingly idiosyncratic collection of substantial Mahayana sutras translated into what Erik Zürcher calls 'broken Chinese' by an Indoscythian, whose Indian name has been reconstructed as Lokaksema." Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004): p. 492

- Skilton 1999, p. 635.

- Indian Buddhism, A.K. Warder, 3rd edition, page 4-5

- Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. p. 336.

- Pettit 2013, p. 44.

- Suzuki 1908, p. 15.

- Bareau, André (1975). "Les récits canoniques des funérailles du Buddha et leurs anomalies : nouvel essai d'interprétation". Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient. 62: 151–189. doi:10.3406/befeo.1975.3845.

- Bareau, André (1979), La composition et les étapes de la formation progressive du Mahaparinirvanasutra ancien, Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient 66, 45-103.

- Reeves 2002, p. 320-22.

- "Though the Buddha had taught [the Mahayana sutras] they were not in circulation in the world of men at all for many centuries, there being no competent teachers and no intelligent enough students: the sutras were however preserved in the Dragon World and other non-human circles, and when in the 2nd century AD adequate teachers suddenly appeared in India in large numbers the texts were fetched and circulated. ... However, it is clear that the historical tradition here recorded belongs to North India and for the most part to Nalanda (in Magadha)." AK Warder, Indian Buddhism, 3rd edition, 1999

- Hsuan Hua. The Buddha speaks of Amitabha Sutra: A General Explanation. 2003. p. 2

- Hirakawa 1990, pp. 253, 263, 268.

- "The south (of India) was then vigorously creative in producing Mahayana sutras" – Warder, A.K. (3rd edn. 1999). Indian Buddhism: p. 335.

- Hirakawa 1990, p. 248-251.

- Hirakawa 1990, p. 252, 253.

- "The sudden appearance of large numbers of (Mahayana) teachers and texts (in North India in the second century AD) would seem to require some previous preparation and development, and this we can look for in the South." - Warder, A.K. (3rd edn. 1999). Indian Buddhism: p. 335.

- "But even apart from the obvious weaknesses inherent in arguments of this kind there is here the tacit equation of a body of literature with a religious movement, an assumption that evidence for the presence of one proves the existence of the other, and this may be a serious misstep." - Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004): p. 493

- "It has become increasingly clear that Mahayana Buddhism was never one thing, but rather, it seems, a loosely bound bundle of many, and — like Walt Whitman — was large and could contain, in both senses of the term, contradictions, or at least antipodal elements.", Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004): 492

- Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004): 492

- "But apart from the fact that it can be said with some certainty that the Buddhism embedded in China, Korea, Tibet, and Japan is Mahayana Buddhism, it is no longer clear what else can be said with certainty about Mahayana Buddhism itself, and especially about its earlier, and presumably formative, period in India.", Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004): 492

- Drewes, David, Mahayana Sutras, forthcoming in Blackwell Companion to South and Southeast Asian Buddhism, Updated 2016

- Williams, Paul, Mahayana Buddhism - The doctrinal foundations, second edition, pp. 50-51.

- Boin-Webb, Sara (tr). Rahula, Walpola (tr). Asanga. Abhidharma Samuccaya: The Compendium of Higher Teaching. 2001. pp. 199-200

- Reat, N. Ross. The Śālistamba sūtra : Tibetan original, Sanskrit reconstruction, English translation, critical notes (including Pali parallels, Chinese version, and ancient Tibetan fragments). Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1993, p. 1.

- Reat, 1993, p. 3-4.

- Potter, Karl H. Abhidharma Buddhism to 150 A.D. page 32.

- Cf. "mu"

- Cf. aum and bīja.

- Huntington, John (2003). The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art: p. 188

- Pye, Michael (2003), Skilful Means - A concept in Mahayana Buddhism, Routledge, pp. 177–178, ISBN 0203503791

- Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse (2009), Interpreting the Lotus Sutra; in: Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; eds. Readings of the Lotus Sutra, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 8, 16, 20–21, ISBN 9780231142885CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013), Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism., Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p. 290, ISBN 9780691157863CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skilton, Andrew. A Concise History of Buddhism. 2004. p. 104

- "The Korean Buddhist Canon: A Descriptive Catalog (T. 361)".

- Mukherjee, Bratindra Nath. India in Early Central Asia. 1996. p. 15

- Inagaki, Hisao, trans. (2003), The Three Pure Land Sutras (PDF), Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, p. xiii, ISBN 1-886439-18-4, archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2014

- Luk, Charles (2002). Ordinary Enlightenment. Shambhala Publications. p. ix. ISBN 1-57062-971-4.

- Luk, Charles (2002). Ordinary Enlightenment. Shambhala Publications. p. x. ISBN 1-57062-971-4.

- Felbur, Rafal (2015). "Vimalakīrtinirdeśa". Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism. 1: 275.

- Thurman, Robert (1998). The Holy Teaching of Vimalakirti. Penn State University Press. p. ix. ISBN 0271006013.

Bibliography

- Dutt, Nalinaksha (1978). Buddhist Sects in India, Motilal Banararsidass, Delhi, 2nd Edition

- Hirakawa, Akira; Groner, Paul (trans.; ed.) (1990), A History of Indian Buddhism, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-1203-4

- Kanno, Hiroshi (2003). Chinese Sutra Commentaries from the Early Period, Annual Report of The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University, IRIAB, vol VI, 301-320

- Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan, 2004.

- McMahan, David (1998). "Orality, writing and authority in South Asian Buddhism: visionary literature and the struggle for legitimacy in the Mahayana". History of Religions. 37 (3): 249–274. doi:10.1086/463504.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nakamura, Hajime (1980). Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes. 1st edition: Japan, 1980. 1st Indian Edition: Delhi, 1987. ISBN 81-208-0272-1

- Nattier, Jan (January 2003). A Few Good Men: The Bodhisattva Path According to the Inquiry of Ugra (Ugraparipṛcchā) : a Study and Translation. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2607-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pettit, John W. (8 February 2013). Mipham's Beacon of Certainty: Illuminating the View of Dzogchen, the Great Perfection. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-719-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skilton, Andrew T (1999). "Dating the Samādhirāja Sūtra". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 27 (6): 635. doi:10.1023/A:1004633623956.

- Thích, Nhất Hạnh (1987). The Sutra on the Eight Realizations of the Great Beings. Parallax Press. ISBN 978-0-938077-07-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pfand, Peter (1986). Māhāyana Texts Translated into Western Languages – A Bibliographical Guide. E.J. Brill, Köln, ISBN 3-923956-13-4

- Reeves, Gene (2002). A Buddhist kaleidoscope: essays on the lotus sutra. Kosei Pub. Co. ISBN 978-4-333-01918-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skilton, Andrew (1997). A Concise History of Buddhism. Windhorse. ISBN 978-0-904766-92-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walser, Joseph. Genealogies of Mahāyāna Buddhism: Emptiness, Power and the question of Origin. Routledge.

- Warder, A. K. (1999). Indian Buddhism. Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi. 3rd revised edition

External links

- Bingenheimer, Marcus (2014). Bibliography of Translations from the Chinese Buddhist Canon into Western Languages

- Buddhist Scriptures in Multiple Languages (Taisho Tripitaka)

- Mahayana Canonical Text Titles and Translations in English

- A Complete Buddhist Sutra Collection

- Mahayana Sutras

- Digital Sanskrit Buddhist Canon

- Mahayana Buddhist Sutras in English

- BuddhaNet's eBook Library (English pdfs)

- Complete English translation and analysis of the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra or PDF

- Bhadra-kalpika Sūtra

- Sūtras