Buddhism in Russia

Historically, Buddhism was incorporated into Siberia in the early 17th century.[1][2] Buddhism is considered to be one of Russia's traditional religions and is legally a part of Russian historical heritage.[3] Besides the historical monastic traditions of Buryatia, Kalmykia and Tuva, Buddhism is now widespread all over Russia, with many ethnic Russian converts.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Vajrayana Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Traditions Historical traditions:

New branches:

|

|

History |

|

Pursuit |

|

Practices

Fourfold division:

Twofold division: Thought forms and visualisation: Yoga:

|

|

Festivals |

|

Tantric texts |

|

Ordination and transmission |

The main form of Buddhism in Siberia is the Gelukpa school of Tibetan Buddhism, informally known as the "yellow hat" tradition,[5] with other Tibetan and non-Tibetan schools as minorities. Although Tibetan Buddhism is most often associated with Tibet, it spread into Mongolia, and via Mongolia into Russia.[1]

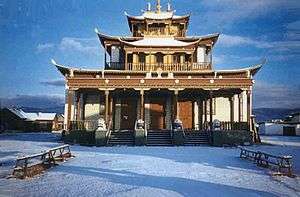

Datsan Gunzechoinei in Saint Petersburg is the northernmost Buddhist temple in Russia.

History

The first evidence of the existence of Buddhism in the territory of the modern Russian (more specifically Siberia, near the lands of East Asian countries) lands belong to the 8th century AD. E. And are associated with the state of Balhae, which in 698-926 occupied part of today's Primorye and Amur. The Mohe, whose culture was greatly influenced by neighboring China, Korea and Manchuria, professed the Buddhism of one of the Mahayana directions. It primarily spread into the Russian constituent regions geographically or culturally adjacent to Mongolia, this region being known as the Mongolian Steppes, or inhabited by Mongolian ethnic groups: Buryatia, Zabaykalsky Krai, Tuva, and Kalmykia, the latter being the only Buddhist region in Europe, located to the north of the Caucasus. By 1887, there were already 29 publishing houses and numerous datsans. These ethnic regions, in 1917, had among them approximately 20,000 followers of the Buddhist faith with 175 temples being erected.[6] When the Soviet Union came into power, it did not welcome the already presiding Buddhists in the country as with most religions with the Soviet Union stating that all religions including Buddhism were to be viewed as "tools of oppression."[7] And by 1917, Joseph Stalin had not allowed any datsans to remain in the country.[8] This was done as the USSR sought to remove Buddhism and other religions, as they found that there would be a link in lack of religion and urbanization to increase production power.[9] In 1929, many monasteries were closed down, and monks were arrested and exiled.[10] By the 1930s, Buddhists were suffering more than any other religious community in the Soviet Union[2] with lamas being expelled and accused of being "Japanese spies" and "the people's enemies".[1] It was by 1943 that all Kalmykians were forcibly exiled to Siberia due to the Soviet Union who had suspicions that they were collaborating with Nazi Germany when they had occupied part of Kalmykia.[11] This caused about 40% of their population to die while in exile and those who did survive would not be able to return to their homeland till 1956.[12]

However Buddhism had not disappeared yet because of Bidia Dandaron a Tsydenov follower as well as a famous Buddhologist and thinker. Dandaron attempted to revive Buddhism in an atheist state by introducing the concept of Neo-Buddhism a combination of Buddhist teachings and current Western philosophy with scientific theories. Dandaron was later arrested for creating a religious community and eventually died within a prison camp, however his disciples played a key role later in the 1990's with the revival of Russian Buddhism.[13]

Revival

After the fall of the Soviet Union, a Buddhist revival began in Kalmykia with the election of President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov.[14] It was also revived in Buryatia and Tuva and began to spread to Russians in other regions.

In 1992, the Dalai Lama made his first visit to Tuva in Russia.[15]

There are several Tibetan Buddhist university-monasteries throughout Russia,[16] concentrated in Siberia, known as Datsans.

Fyodor Shcherbatskoy, a renowned Russian Indologist who traveled to India and Mongolia during the time of the Russian Empire, is widely considered by many to be responsible for laying the foundations for the study of Buddhism in the Western world.

There are now between 700,000 and 1.5 million Buddhists in Russia, mainly in the republics of Buryatia, Kalmykia and Tuva.[17]

Regions with large Buddhist populations

| Federal subject | Buddhists (2012)[18] | Buddhists (2016)[19] |

|---|---|---|

| 61.8% | 52.2% | |

| 37.6% | 53.4% | |

| 19.8% | 19.8% | |

| 6.3% | 14.6% | |

| 0.5% | 0.6% |

.png)

In 2012 it was the religion of 62% of the total population of Tuva, 38% of Kalmykia and 20% of Buryatia.[18] Buddhism also has believers accounting for 6% in Zabaykalsky Krai, primarily consisting in ethnic Buryats, and of 0.5% to 0.9% in Tomsk Oblast and Yakutia. Buddhist communities may be found in other federal subjects of Russia, between 0.1% and 0.5% in Sakhalin Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai, Amur Oblast, Irkutsk Oblast, Altay, Khakassia, Novosibirsk Oblast, Tomsk Oblast, Tyumen Oblast, Orenburg Oblast, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Murmansk Oblast, Moscow and Moscow Oblast, Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast, and in Kaliningrad Oblast.[18] In cities like Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Samara, often up to 1% of the population identify as Buddhists.[20]

See also

- Buddhism in Buryatia

- Buddhism in Kalmykia

- Datsan - Buddhist temples in Russia

- Datsan Gunzechoinei

References

- "Buddhism in Russia". buddhist.ru. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- Troyanovsky, Igor. "Buddhism in Russia". www.buddhismtoday.com. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- Bell, I (2002). Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia. ISBN 978-1-85743-137-7. Retrieved 27 Dec 2007.

- Research Article- Ostrovskaya - JGB Volume 5 Archived 2007-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Holland, Edward C. (Dec 2014). "Buddhism in Russia: challenges and choices in the post-Soviet period". Religion, State and Society. 42 (4): 389–402. doi:10.1080/09637494.2014.980603.

- "2. Buddhist Temples for the Elites", Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art, 1600–2005, University of Hawaii Press, 2017-12-31, pp. 45–72, doi:10.1515/9780824862466-006, ISBN 9780824862466

- Bernstein, Anna (2002). "Buddhist Revival in Buriatia: Recent Perspectives". Mongolian Studies. 25: 1–11. ISSN 0190-3667. JSTOR 43193334.

- Weir, Fred (2018). "Buddhism flourishes in Siberia, opening window on its pre-Soviet past.(World)". The Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- Timasheff, N. S. (1955). "Urbanization, Operation Antireligion and the Decline of Religion in the USSR". American Slavic and East European Review. 14 (2): 224–238. doi:10.2307/3000744. ISSN 1049-7544. JSTOR 3000744.

- Bräker, Hans (1981). Der Buddhismus in der Sowjetunion, Cahiers du Monde russe et soviétique 22 (2/3), p. 333

- Holland, Edward C. (2014-10-02). "Buddhism in Russia: challenges and choices in the post-Soviet period". Religion, State and Society. 42 (4): 389–402. doi:10.1080/09637494.2014.980603. ISSN 0963-7494.

- "Chapter 3. Tibet", The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Princeton University Press, 2011-12-31, pp. 49–70, doi:10.1515/9781400838042-005, ISBN 978-1-4008-3804-2

- "Buddhism in Russia: History and Modernity | Buddhistdoor". www.buddhistdoor.net. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- Буддизм в России

- "RUSSIA: When will Dalai Lama next visit Tuva? - WWRN - World-wide Religious News". wwrn.org. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Tricycle. "lettucecomic". Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Putin Promises 100% Support for Buddhists". Ria Novosti. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Арена: Атлас религий и национальностей" [Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities] (PDF). Среда (Sreda). 2012. See also the results' main interactive mapping and the static mappings: "Religions in Russia by federal subject" (Map). Ogonek. 34 (5243). 27 August 2012. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. The Sreda Arena Atlas was realised in cooperation with the All-Russia Population Census 2010 (Всероссийской переписи населения 2010) and the Russian Ministry of Justice (Минюста РФ).

- "ФСО доложила о межконфессиональных отношениях в РФ". ZNAK. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Filatov & Lunkin 2006, p. 38.

Bibliography

- Juergensmeyer, Mark (2006). The Oxford Handbook of Global Religions. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-0-19-972761-2.

- Ulanov, Mergen; Badmaev, Valeriy and Holland, Edward (2017). Buddhism and Kalmyk Secular Law in the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries, Inner Asia 19(2), 297–314

- Terentyev, Andrey (Autumn 1996).Tibetan Buddhism in Russia, The Tibet Journal 21 (3), pp. 60–70

External links

- The Buddhist hordes of Kalmykia, The Guardian September 19, 2006

- Buddhactivity Dharma Centres database

- Gusinoye Ozero, seat of imperial Russia's Buddhists

- Buddhist Paintings in Buryatia

- History of Tibetan Buddhism in Inner Asia in the 20th Century

- Buryats culture and traditions

- Pandito Khambo Lama Itigelov's Most Precious Body 10/9/05)