Heyward Shepherd monument

The Heyward Shepherd monument, in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, was erected in 1931, after decades of controversy, by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and, to a lesser extent, by the Sons of Confederate Veterans.[1] It commemorates Heyward (sometimes spelled "Hayward" or "Heywood") Shepherd (1825 – October 16, 1859), a free black man, who was the first person killed during John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. The monument was intended to document the Lost Cause allegation that there were happy, unrebelious slaves (the UDC had a "Faithful Slave Memorial Committee"). There is no evidence that Shepherd was born a slave or that he was opposed to John Brown's attempt to end American slavery or even that he had heard of it. Nevertheless, the monument was intended to be a reply to blacks' glorification of Brown, in whose honor Storer College had been established in Harpers Ferry and placed a plaque on the Armory in 1918.[1][2] There was no better place, from the UDC's point of view, for a monument to the "happy slave" than Harpers Ferry.

According to Caroline Janney,

[T]he Heyward Shepherd monument and the controversy that surrounded it serves as a rare instance in which white and black memories overtly confronted one another and one in which white "victory" was not guaranteed. Framed in terms of gender, race, and heroism, the debate reflected much larger ideas about slavery, race relations, and resistance to violence in the early twentieth century.... By the mid-1930s, neither side seemed interested in the specifics of the raid, Shepherd's death, or even his status as a slave or freedman. Over the course of the debate, both whites and blacks had struggled with images of gender and heroism and eventually found themselves embroiled in a struggle over mythic symbols. Shepherd, for the UDC, and Brown, for the NAACP, became emblematic of larger social concerns: what the relationship between the two races should be in the wake of slavery and the role of violence in that relationship.[1]

Heyward Shepherd

Heyward Shepherd was a free black man who lived in Winchester, Virginia, about 30 miles (48 km) from Harpers Ferry. He owned property there, a small house, and had a wife and five children, according to the 1860 census. "It is unclear whether Shepherd was born a free man or was an emancipated slave because various anecdotal references present different opinions on that subject."[3]:note 8 While presenting him as the "happy slave," the thought of confirming his status never crossed the Daughters' minds.[1]

He had worked for "ten or twelve years" as a porter or baggage handler with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, whose trains went back and forth through Harpers Ferry, an important rail junction. The stationmaster was Fontaine Beckham, the mayor of Harpers Ferry; when he was absent, Shepherd was in charge of the station. Beckham, who also was killed, "liked him very much."[4]

What happened, as described by Shepherd to the physician who treated him, John D. Starry, was "that he had been out on the railroad bridge looking for a watchman who was missing, and he had been ordered to halt by some men who were there, and, instead of doing that, he turned to go back to the office, and as he turned they shot him in the back."[5] That was enlarged by the UDC, without documentary foundation, into his rejection of John Brown and an attempt to warn the whites of Harpers Ferry.

He was buried in the Winchester–Fairfax Colored Cemetery without a grave marker. He was "accorded public honors by the state of Virginia, his funeral being attended by a detachment of the Virginia State militia."[6]

Monuments

There has been contention throughout the 20th century as to what plaque, if any, should be displayed next to the UDC's memorial. "Today the Heyward Shepherd Memorial stands not as a representative of a community's collective remembrance, but rather as a testament to the struggle between Southern whites and African Americans to write their respective memories of the raid into the historical landscape."[1]

1918 plaque to Brown

The origin of the monument to the "faithful slave" is the monument to Brown, posted on the original building, the "firehouse," which had been moved to the campus of Storer College:[7]

THAT THIS NATION MIGHT HAVE

NEW BURST OF FREEDOM

THAT SLAVERY SHOULD BE REMOVED

FOREVER FROM AMERICAN SOIL

JOHN BROWN

AND HIS 21 MEN GAVE THEiR

LIVES

TO COMMEMORATE THEIR

HEROISM THIS TABLET IS

PLACED ON THIS BUILDING

WHICH HAS SINCE BEEN

KNOWN AS

JOHN BROWN'S FORT

BY THE

ALUMNI OF STORER COLLEGE

1918

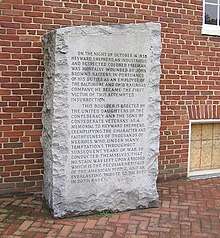

1931 monument

In 1931, after opposition since it had been proposed in 1920,[8] what was called at the time the Faithful Slave Memorial[8] was erected by the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (39°19′24″N 77°43′48″W). The text of the granite monument reads:

On the night of October 16, 1859, Heyward Shepherd, an industrious and respected colored freeman, was mortally wounded by John Brown's raiders. In pursuance of his duties as an employee of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company, he became the first victim of this attempted insurrection.

This boulder is erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans as a memorial to Heyward Shepherd, exemplifying the character and faithfulness of thousands of negros who, under many temptations throughout subsequent years of war, so conducted themselves that no stain was left upon a record which is the peculiar heritage of the American people, and an everlasting tribute to the best in both races.[8]

1932 plaque

The monument was immediately challenged by many as perpetuating the "faithful slave" concept of slavery as a justification for the practice.

The NAACP responded by preparing a plaque to be displayed at Storer College in Harpers Ferry, where the firehouse used by John Brown as a fort had been moved. The text on the plaque was written by W. E. B. Du Bois, biographer of John Brown and NAACP cofounder.[9][10] Henry T. MacDonald, the white president of the College, who had participated in the UDC's 1931 ceremony,[11] refused to allow the plaque to be mounted. In 2006, 74 years later, the plaque was finally placed on the side of the firehouse, which, in 1968, had been moved from the closed college to as close to its former location, now covered by an embankment, as possible.[12] The plaque reads:[13]

HERE

JOHN BROWN

AIMED AT HUMAN SLAVERY

A BLOW

THAT WOKE A GUILTY NATION.

WITH HIM FOUGHT

SEVEN SLAVES AND SONS OF SLAVES.

OVER HIS CRUCIFIED CORPSE

MARCHED 200,000 BLACK SOLDIERS

AND 4,000,000 FREEDMEN

SINGING

"JOHN BROWN'S BODY LIES

A-MOULDERING IN THE GRAVE

BUT HIS SOUL GOES MARCHING ON!"

IN GRATITUDE THIS TABLET IS ERECTED

THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

MAY 21, 1932

1955 plaque

A plaque to contextualize the original 1931 monument was placed in 1955 by the National Park Service. The text of the plaque read:

John Brown's raid on the armory at Harpers Ferry caused the death of four townspeople. One of those who died in the fighting was Heyward Shepherd, a railroad baggagemaster and a free black. Although the true identity of his assailant is uncertain, Shepherd soon became a symbol of the "faithful servant" among those who deplored Brown's action against the traditional southern way of life. The monument, placed here in 1931, reflects those traditional views.

The monument was in storage from 1976 to 1980 and then shrouded in plywood until 1995.[1]

1994 plaque

Another plaque was installed near the 1931 monument by the National Park Service, to place the monument in context. It reads:

On October 17, 1859, abolitionist John Brown attacked Harpers Ferry to launch a war against slavery. Heyward Shepherd, a free African-American railroad baggage master, was shot and killed by Brown's men shortly after midnight. Seventy-two years later, on October 10, 1931, a crowd estimated to 300 whites and 100 blacks gathered to unveil and dedicate the Shepherd Monument. During the ceremony, voices rose to praise and denounce the monument. Conceived around the turn of the century, the monument endured controversy. In 1905, the United Daughters of the Confederacy stated that erecting the monument would influence for good the present and coming generations, and prove that the people of the South who owned slaves valued and respected their good qualities as no one else ever did or will do.

References

- Janney, Caroline E. (2006). "Written in Stone: Gender, Race, and the Heyward Shepherd Memorial". Civil War History. 52 (2). pp. 117–141.

- "Plaque in Harpers Ferry WV". 1918. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- Johnson, Mary (1997). "An 'Ever Present Bone of Contention': the Heyward Shepherd Memorial". West Virginia History. 56: 1–26.

- "An incident of the rebellion". Baltimore Sun. October 25, 1859. p. 1.

- United States Congress. Senate. Select Committee on the Harper's Ferry Invasion (1860). Mason, John Murray (ed.). "Senate Select Committee Report on the Harper's Ferry Invasion". p. 23.

- "Heyward 'Hayward' Shepherd". findagrave.com. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- Hamilton, Calvin J. "John Brown's Fort". scienceviews.com. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- Johnson, Mary (2015). "Heyward Shepherd". e-WV The West Virginia Encyclopedia. West Virginia Humanities Council.

- Tasker, Greg (September 3, 1995). "Tribute to victim of Brown's raid still controversial". Baltimore Sun.

- Hawks, Steve A. (2019). "Harpers Ferry History marker". Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- "Tablet to Shepherd, John Brown Raider Victim, Unveiled". Chicago Tribune. October 11, 1931. p. 16 – via newspapers.com.

- Straley, Steven C. (2017). "NAACP Tablet Commemoration". Clio.

- "John Brown". Historical Markers Database. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

Further reading

- Holloway, Kali (March 25, 2019). "'Loyal Slave' Monuments Tell a Racist Lie About American History". The Nation.

- Holloway, Kali (October 16, 2018). "The Heyward Shepherd Monument: An Overt Ode to Slavery". Independent Media Institute.

- Holloway, Kali (October 11, 2018). "Heyward Shepherd 'tribute' is a racist relic that must come down". Spirit of Jefferson (Charles Town, West Virginia).

- Levin, Kevin M. (August 17, 2017). "The Pernicious Myth of the 'Loyal Slave' Lives on in Confederate Memorials". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Hayes, Dianne. "NAACP Retraces History at Harpers Ferry." Diverse: Issues in Higher Education 23, no. 13 (August 10, 2006): 17.

- Johnson, Mary (1997). "An 'Ever Present Bone of Contention': the Heyward Shepherd Memorial". West Virginia History. 56: 1–26.

- "Monument to First Black Killed at Harpers Ferry Draws Criticism". Jet. September 18, 1995. pp. 22–23.

- Andrews, Matthew Page. Heyward Shepherd, Victim of Violence. Address of Dedication at the Unveiling of the Heyward Shepherd Monument, at Harpers Ferry, October 10, 1931. [Harpers Ferry, W. Va.?]: Published under the auspices of the Heyward Shepherd Memorial Association, 1931.

- McDonald, Henry Temple. Henry Temple McDonald Papers. 1864. Abstract: Material relating to McDonald's efforts to recognize and promote Storer College, Harpers Ferry, W. Va., local historic sites, and Harpers Ferry National Monument now known as Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. Includes correspondence to and from McDonald with carbon copies of his outgoing letters sometimes typed on the reverse side of Storer College stationery or announcements; drafts and final copies of speeches and lectures McDonald presented on many occasions in the local area; manuscripts including drafts and carbon copies; and research items including bibliographies.