First Battle of Newtonia

The First Battle of Newtonia was an American Civil War battle fought on September 30, 1862, near Newtonia, Missouri. A Confederate force commanded by Colonel Douglas H. Cooper moved into southwestern Missouri, and encamped near the town of Newtonia. The Confederate column was composed mostly of cavalry led by Colonel Joseph O. Shelby and a brigade of Native Americans. A Union force commanded by Brigadier General James G. Blunt moved to intercept Cooper's force. Blunt's advance force, led by Brigadier General Frederick Salomon, reached the vicinity of Newtonia on September 29, and attacked Cooper's position at Newtonia on September 30. A Union probing force commanded by Colonel Edward Lynde was driven out of Newtonia by Cooper's forces on the morning of the 30th.

First Battle of Newtonia Historic District | |

| |

| Nearest city | Newtonia, Missouri |

|---|---|

| Area | 152.3 acres (61.6 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 04000697[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 23, 2004[2] |

Both sides brought up further reinforcements, and seesaw fighting took place during much of the afternoon. Shortly before nightfall, Cooper's Confederates made an all-out attack against the Union line; this led Salomon to withdraw from the field. The Unionist militia commanded by Colonel George Hall covered the Union retreat, although the Confederate artillery fire struck the retreating Union forces. This panicked some of Salomon's men, and the retreat turned into a disorderly rout. A large Union force began advancing towards Newtonia in early October; leading Cooper to abandon Missouri. A portion of the battlefield was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004 as the First Battle of Newtonia Historic District.

Background

After Union victories at the Battle of Pea Ridge and the Battle of Island Number Ten in early 1862,[3] the Union control of Missouri seemed secure, with the Union high command proclaiming that "[there was] no Rebel flag now flying in Missouri".[4] This claim was soon disproved. Confederate Major General Sterling Price sent some of his troops into Missouri to obtain supplies and recruit new volunteers. The state was also raided by Confederate forces such as those under Colonel Joseph C. Porter, [5] and was plagued by guerilla attacks from prominent bushwhackers including William Quantrill. At one point Quantrill's guerrillas combined with a regular Confederate force commanded by Colonel John T. Hughes. This combined force defeated a Union force at the First Battle of Independence on August 11.[6] The Union forces suffered another defeat on August 15, this time at the Battle of Lone Jack.[7] The resurgence in Confederate activity proved to be an embarrassment to the commander of the Union's Department of the Missouri, Brigadier General John M. Schofield. Schofield was replaced by Major General Samuel R. Curtis and relegated to the command of the Army of the Frontier.[8]

During this time of increased Confederate activity in Missouri, Confederate Colonel Douglas H. Cooper began an incursion into the southwestern portion of the state. Cooper's force included the Confederate cavalry of Colonel Joseph O. Shelby, as well as a brigade of Confederate-sympathizing Native Americans and several Texas cavalry regiments.[9] A Union force commanded by Brigadier General James G. Blunt and spearheaded by Brigadier General [[Frederick Salomon began moving to confront the Confederates.[10] Cooper sent a scouting force to the Newtonia area on September 27. Commanded by Colonel Trezevant C. Hawpe, it was composed of the 31st Texas Cavalry Regiment and the 1st Cherokee Battalion. Hawpe determined that Newtonia, which was a communications hub, would be a good encampment and had his troops begin operating a grist mill to produce flour for the Confederate army. After receiving Hawpe's recommendation, Cooper ordered Hawpe to remain in Newtonia and reinforced him with Captain Joseph Bledsoe's Battery. On September 28, Hawpe was informed by local residents that Union troops were advancing to Granby, but Confederate scouts found no evidence of this movement.[11] Meanwhile, Union forces began concentrating in southwestern Missouri. Two brigades under Colonel William A. Weer and Brigadier General Frederick Salomon rendezvoused at Sarcoxie on September 28, and Colonel James Totten's division was expected to leave Springfield on September 29.[12]

Opposing forces

Union

The Union force engaged at Newtonia was a mixture of all three arms of the Union Army: infantry, cavalry, and artillery. Union cavalry consisted of the 6th Kansas Cavalry, 9th Kansas Cavalry, 2nd Ohio Cavalry, and the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry. Infantry regiments present at the battle were the 10th Kansas Infantry, 13th Kansas Infantry, and the 9th Wisconsin Infantry. Artillery came from the 1st Kansas Light Artillery, 2nd Kansas Light Artillery, and the 25th Ohio Battery. Also present was the 3rd Indian Home Guard.[13] Historian Shelby Foote would later estimate the total strength of the Union column to be about 4,000 men,[14] although other sources give an estimate of 4,500.[15] The Union artillery batteries contained 12 cannons.[16] Three of the cannons were 3-inch rifles and two were mountain howitzers.[17]

Confederate

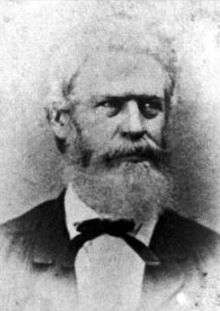

The Confederate forces at Newtonia included the 1st Cherokee Battalion, the 1st Choctaw Regiment, the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles, Colonel A. M. Alexander's 34th Texas Cavalry Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Beal G. Jeans' Missouri Cavalry Regiment,[lower-alpha 1] Hawpe's 31st Texas Cavalry Regiment, Shelby's 5th Missouri Cavalry Regiment ,[lower-alpha 2] Colonel James G. Stevens' 22nd Texas Cavalry Regiment, Bledsoe's Battery, and Captain Sylvanus Howell's Battery.[20] Foote estimated the total Confederate strength to be around 5,500 men,[14] an estimate that is consistent with the range found in other sources.[21][lower-alpha 3]

Battle

Preliminary action

On September 29, Salomon sent a 150-man scouting force towards Newtonia, commanded by Colonel Edward Lynde from the 9th Kansas Cavalry. Lynde's men drove Confederate skirmishers back towards Newtonia, and determined that a strong enemy force occupied the town. Hawpe, still commanding the Confederates in Newtonia, reported the Union probe to Cooper, who sent two regiments of Shelby's cavalry to Newtonia. After realizing that his cannons lacked the range to shell Newtonia, Lynde ordered a retreat.[22] Salomon noted the sounds of combat coming from the Newtonia area, and sent a detachment of the 9th Wisconsin Infantry to support Lynde.[23]

September 30

The detachment from the 9th Wisconsin reached the Newtonia area on the morning of September 30. The Wisconsin soldiers quickly encountered Confederate resistance, although they were soon joined by Lynde's cavalrymen, who had returned to the Newtonia area. Lynde also brought two mountain howitzers with his force.{{efn|The mountain howitzers were from Company "F" of the 9th Kansas Cavalry.[24] Hawpe responded to the start of the action by reporting the Union advance to Cooper. The Confederates, represented by the 31st Texas Cavalry, the 1st Cherokee Battalion, and Bledsoe's artillery, took up defensive positions near Mathew H. Ritchey's farm.[25] Union reinforcements brought the number of cannons Lynde had available to five, and a sharp artillery duel began. The artillery exchange remained deadlocked until the Union artillery advanced nearer to the Confederate lines, which allowed their fire to become more effective. Some of the infantrymen of the 9th Wisconsin moved to the cover of the houses on the edge of Newtonia; they began sniping at the cannoneers of Bledsoe's battery. Cooper noticed that sounds of battle were coming from Newtonia, and sent the 34th Texas Cavalry to Newtonia to reinforce Hawpe.[26]

The Texans had been taking shelter behind a stone wall, but left the cover of the stone wall to assault the Union line. The charge was quickly repulsed by canister fire from the Union artillery. After charge was repulsed, the Union artillery concentrated again on Bledsoe's battery, which they soon forced to withdraw a short distance. Bledsoe's guns ran low on ammunition after about 30 minutes, and when the Union commanders saw the Confederate artillery fire slacken, the 9th Wisconsin charged the Confederate line.[27] At this time, Confederate reinforcements in the form of the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles and the 5th Missouri Cavalry arrived. The fresh units were enough to turn the tide against the 9th Wisconsin, which retreated from Newtonia. Additionally, the 22nd Texas Cavalry, which had been in the Granby area, arrived to further strengthen the Confederates. The 22nd Texas had planned on assaulting the Union artillery position, but the Missouri cavalry, commanded by Colonel B. Frank Gordon, mistook the Texans for Union troops, and the delay caused by the confrontation eliminated the opportunity for an assault.[28] Lynde and the commander of the 9th Wisconsin decided to begin a withdrawal, although a delayed charge by Gordon's cavalry interfered with the process. The Confederate charge was again dispersed with canister fire, after which the Union retreat began. The Confederates pursued, and the retreat soon became disorderly.[29]

Like Cooper, Salomon learned about the fighting by hearing the sounds of battle coming from Newtonia. In response, Salomon sent the 6th Kansas Cavalry and the 3rd Indian Home Guard towards the town.[30] The two regiments encountered the Confederates pursuing Lynde's column, and the pursuit ended in the face of fresh Union troops. In the interim, two more Confederate units had reached Newtonia: Jeans' cavalry regiment and four cannons under the command of Howell. The Confederates were aware that additional Union soldiers were coming, and Howell placed his cannons in a position where they commanded the road the Union troops were advancing down. Once the Union troops came within view, Howell began shelling the column, which retreated out of range of the cannons.[31]

The repulse of the 6th Kansas Cavalry and 3rd Indian Home Guard had occurred in the mid-morning of the 30th, and no more serious fighting occurred until the early afternoon. Salomon had left Sarcoxie earlier, but did not reach the Union line until about 3:30 in the afternoon. He then proceeded to form a defensive line with the cannons on hand, as well as the 6th Kansas Cavalry, the 3rd Indian Home Guard, and a portion of the 9th Wisconsin. Some of the cannon crews that had seen heavy fighting in Lynde's morning action, along with the 10th Kansas Infantry, formed a reserve. The Union guns began an artillery duel with Howell's cannons, and the Confederate cannoneers were soon forced to retreat. An attempt by the Confederates to use the Ritchey barn as a fortification proved futile once the Union guns found the range of the structure. Meanwhile, the Confederates were again reinforced: Bledsoe's battery returned after an ammunition-gathering expedition, and the 1st Choctaw Regiment arrived.[32]

Cooper then sent Jeans' Regiment and the 22nd Texas Cavalry to probe the Union line, but artillery fire and the 3rd Indian Home Guard drove back the Confederate probe. The 3rd Indian Home Guard pursued the retreating Confederates, threatening the stability of the main Confederate line, but a counterattack by the 1st Choctaw Regiment and the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles stabilized the situation. Salomon sent the 10th Kansas Infantry into the fray to support the 3rd Indian Home Guard, but fire from Howell's Confederate artillery and an advance by the 22nd Texas Cavalry compelled the Union troops to break off the assault.[32] Cooper responded by initiating an attack with his entire force against the Union line. Salomon then ordered a withdrawal, and the Union troops began to retreat from the field.[33]

A brigade of Unionist Missouri state militia forces commanded by Colonel George Hall arrived on the field as Salomon was ordering his retreat. Hall was ordered to cover the Union retreat, and the militia formed a line between Salomon's retreating force and the pursuing Confederates. A few pieces of the Union artillery had remained in fighting order, and these guns supported Hall's line. Darkness hampered the effectiveness of the Union cannons, but Howell's artillery responded, using the muzzle flashes of the Union cannons as aiming points. The Confederate fire did just enough to panic the Union forces, and the orderly retreat turned into a rout.[34] Some of the Union soldiers fled all the way to Sarcoxie, which was about 10 miles (16 km) away from Newtonia.[35] By this point, darkness had fallen, and neither army wished to bring on a night battle. After Salomon's troops had left the battlefield, Hall's militiamen withdrew in turn, although they still provided a rear guard. Around the same time, Cooper called off the pursuit. The 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles failed to receive the order and Cooper later sent an officer to retrieve the regiment, ordering it back to the Confederate camp.[36]

Aftermath

During the battle at Newtonia, the Confederates suffered 78 casualties, while the Union lost 245 men.[35] Confederate casualties were the highest in the 5th Missouri Cavalry, which lost four men killed and 11 wounded, for a total of 15. The Confederates also lost 15 officers, including one killed in each of the 1st Choctaw Regiment and the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles.[20] The Union losses were highest in the 9th Wisconsin and the 9th Kansas Cavalry.[37]

Despite defeating Salomon's Union force, the Confederate position around Newtonia was still not secure. Salomon's command had represented only the advance guard of a much larger Union force.[38] By October 4, Cooper had decided to abandon Newtonia and southwestern Missouri. Shelby's cavalry was tasked with remaining in Newtonia to serve as a rear guard. However, he did not remain in Newtonia long, as he soon received word that his line of retreat was in danger of being cut off by the Union advance. Shelby fell back, and the Union troops occupied Newtonia after a brief shelling of the town.[39] The Confederate Native American troops retreated back to Indian Territory,[38] and the rest of the Confederates retreated into northwestern Arkansas.[35] As the Confederates engaged at Newtonia retreated from Missouri, other Confederate troops attacked and forced the surrender of a small Union garrison at the Battle of Clark's Mill.[40] First Newtonia was the first battle in the American Civil War that saw Native Americans fight on both sides in an organized manner.[41]

On October 28, 1864, the Second Battle of Newtonia was fought near the site of the 1862 battle. In the 1864 battle, a Union army commanded by Blunt attacked and defeated a Confederate army led by Sterling Price. The Confederates had been retreating southwards after being defeated at the battles of Westport, Missouri, and Mine Creek, Kansas. Shelby played a prominent role for the Confederates in the Second Battle of Newtonia, much as he did in the 1862 battle.[42]

Preservation

The First Battle of Newtonia Historic District preserves 152.3 acres (61.6 ha) of the battlefield; the district was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. The separately listed Mathew H. Ritchey House is in the district. The district also includes the Ritchey barn and barnyard site, a Civil War-era cemetery, the Newtonia Branch stream, the historic Neosho Road, and the battlefield itself. While much of the land in the district is privately owned, the Newtonia Battlefields Protection Association has ownership of 20 acres (8.1 ha). At least nine burials are those of Union soldiers, although not all of them are related to the First Battle of Newtonia. More war-related burials had previously been located, as many of the military burials were exhumed and moved to the Springfield National Cemetery in 1869.[1] The American Battlefield Protection Program has suggested that it may be possible to enlarge the area of the historic district. However, the same study determined that the site did not meet the inclusion criteria for becoming an official unit of the National Park Service, as the resources available for preservation at Newtonia were too similar to those already preserved in other National Park Service sites.[43] The Mathew H. Ritchey house is particularly notable, as it served as a headquarters building for both sides during the two battles of Newtonia[44] and was used as a field hospital after the fighting.[41] The Civil War Trust has acquired and preserved 8 acres (3.2 ha) of the Newtonia battlefield.[44]

See also

Notes

References

- Laura A. Hazelwood, Matt Stith, Tiffany Patterson, and Roger Maserang (May 2004). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: First Battle of Newtonia Historic District" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved June 7, 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "National Register of Historic Places 2005 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- Gerteis 2012, pp. 138, 141.

- Gerteis 2012, p. 138.

- Gerteis 2012, p. 141.

- Gerteis 2012, pp. 144–145.

- Gerteis 2012, pp. 146–147.

- Gerteis 2012, p. 149.

- Gerteis 2012, p. 147.

- Gerteis 2012, pp. 147–148.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 286–287.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 291–292.

- "Missouri Civil War Battles". National Park Service. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Foote 1958, p. 784.

- Wood 2010, p. 89.

- O'Flaherty 2000, pp. 124–125.

- Bearss 1966, p. 299.

- McGhee 2008, pp. 97–99.

- Official Records 1880, p. 298.

- Official Records 1880, p. 301.

- O'Flaherty 2000, p. 125.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 292–293.

- Bearss 1966, p. 295.

- Official Records 1880, p. 291.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 296–300.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 301–302.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 303–304.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 304–305.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 306–308.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 308–310.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 310–312.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 313–316.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 316–318.

- Wood 2010, pp. 86–88.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 134.

- Bearss 1966, pp. 318–319.

- Bearss 1966, p. 319.

- O'Flaherty 2000, p. 126.

- Wood 2010, pp. 94–96.

- Gerteis 2012, pp. 148–149.

- Ostmeyer, Andy. "Damnable Time". The Joplin Globe. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- "Second Battle of Newtonia". battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- "Newtonia Battlefields Special Resource Study" (PDF). National Park Service. 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- "Newtonia Battlefield". battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

Sources

- Bearss, Edwin (April 1966). "The Army of the Frontier's First Campaign: The Confederates Win at Newtonia". Missouri Historical Review. State Historical Society of Missouri. 60 (3): 283–319. ISSN 0026-6582. OCLC 1758409.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foote, Shelby (1958). The Civil War: A Narrative. Volume 1, Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-74623-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gerteis, Louis S. (2012). The Civil War in Missouri. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1972-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGhee, James E. (2008). Guide to Missouri Confederate Regiments, 1861–1865. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-870-7.

- O'Flaherty, Daniel O. (2000). General Jo Shelby: Undefeated Rebel (reprint ed.). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4878-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1880. p. 301. OCLC 262466842.

- Wood, Larry (2010). The Two Civil War Battles of Newtonia. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 1-59629-857-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)