Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Passage, and existed from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The vast majority of those who were enslaved and transported in the transatlantic slave trade were people from Central and West Africa, who had been sold by other West Africans, or by half European 'merchant princes' [1] to Western European slave traders (with a small number being captured directly by the slave traders in coastal raids), who brought them to the Americas.[2] Except for the Portuguese, European slave traders generally did not participate in the raids because life expectancy for Europeans in sub-Saharan Africa was less than one year during the period of the slave trade (which was prior to the development of quinine as a treatment for malaria).[3] The South Atlantic and Caribbean economies were particularly dependent on labour for the production of sugarcane and other commodities. This was viewed as crucial by those Western European states which, in the late 17th and 18th centuries, were vying with each other to create overseas empires.[4]

.jpg)

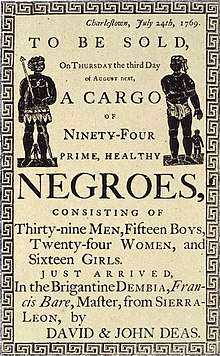

The Portuguese, in the 16th century, were the first to engage in the Atlantic slave trade. In 1526, they completed the first transatlantic slave voyage to Brazil, and other Europeans soon followed.[5] Shipowners regarded the slaves as cargo to be transported to the Americas as quickly and cheaply as possible,[4] there to be sold to work on coffee, tobacco, cocoa, sugar, and cotton plantations, gold and silver mines, rice fields, the construction industry, cutting timber for ships, in skilled labour, and as domestic servants. The first Africans kidnapped to the English colonies were classified as indentured servants, with a similar legal standing as contract-based workers coming from Britain and Ireland. However, by the middle of the 17th century, slavery had hardened as a racial caste, with African slaves and their future offspring being legally the property of their owners, as children born to slave mothers were also slaves (partus sequitur ventrem). As property, the people were considered merchandise or units of labour, and were sold at markets with other goods and services.

The major Atlantic slave trading nations, ordered by trade volume, were the Portuguese, the British, the Spanish, the French, the Dutch Empires, and the Danish. Several had established outposts on the African coast where they purchased slaves from local African leaders.[6] These slaves were managed by a factor, who was established on or near the coast to expedite the shipping of slaves to the New World. Slaves were imprisoned in a factory while awaiting shipment. Current estimates are that about 12 million to 12.8 million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic over a span of 400 years.[7][8]:194 The number purchased by the traders was considerably higher, as the passage had a high death rate with approximately 1.2–2.4 million dying during the voyage and millions more died in seasoning camps in the Caribbean after arrival to the New World. Millions of slaves also died as a result of slave raids, wars and during transport to the coast for sale to European slave traders.[9][10][11][12] Near the beginning of the 19th century, various governments acted to ban the trade, although illegal smuggling still occurred. In the early 21st century, several governments issued apologies for the transatlantic slave trade.

Background

Atlantic travel

The Atlantic slave trade developed after trade contacts were established between the "Old World" (Afro-Eurasia) and the "New World" (the Americas). For centuries, tidal currents had made ocean travel particularly difficult and risky for the ships that were then available. Thus, there had been very little, if any, maritime contact between the peoples living in these continents.[13] In the 15th century, however, new European developments in seafaring technologies resulted in ships being better equipped to deal with the tidal currents, and could begin traversing the Atlantic Ocean; the Portuguese set up a Navigator's School (although there is much debate about whether it existed and if it did, just what it was). Between 1600 and 1800, approximately 300,000 sailors engaged in the slave trade visited West Africa.[14] In doing so, they came into contact with societies living along the west African coast and in the Americas which they had never previously encountered.[15] Historian Pierre Chaunu termed the consequences of European navigation "disenclavement", with it marking an end of isolation for some societies and an increase in inter-societal contact for most others.[16]

Historian John Thornton noted, "A number of technical and geographical factors combined to make Europeans the most likely people to explore the Atlantic and develop its commerce".[17] He identified these as being the drive to find new and profitable commercial opportunities outside Europe. Additionally was the desire to create an alternative trade network to that controlled by the Muslim Ottoman Empire of the Middle East, which was viewed as a commercial, political and religious threat to European Christendom. In particular, European traders wanted to trade for gold, which could be found in western Africa, and also to find a maritime route to "the Indies" (India), where they could trade for luxury goods such as spices without having to obtain these items from Middle Eastern Islamic traders.[18]

Although many of the initial Atlantic naval explorations were led by Iberians, members of many European nationalities were involved, including sailors from Portugal, Spain, the Italian kingdoms, England, France and the Netherlands. This diversity led Thornton to describe the initial "exploration of the Atlantic" as "a truly international exercise, even if many of the dramatic discoveries were made under the sponsorship of the Iberian monarchs". That leadership later gave rise to the myth that "the Iberians were the sole leaders of the exploration".[19]

African slavery

Slavery was prevalent in many parts of Africa[20] for many centuries before the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade. There is evidence that enslaved people from some parts of Africa were exported to states in Africa, Europe, and Asia prior to the European colonization of the Americas.[21]

The Atlantic slave trade was not the only slave trade from Africa, although it was the largest in volume and intensity. As Elikia M'bokolo wrote in Le Monde diplomatique:

The African continent was bled of its human resources via all possible routes. Across the Sahara, through the Red Sea, from the Indian Ocean ports and across the Atlantic. At least ten centuries of slavery for the benefit of the Muslim countries (from the ninth to the nineteenth) ... Four million enslaved people exported via the Red Sea, another four million[22] through the Swahili ports of the Indian Ocean, perhaps as many as nine million along the trans-Saharan caravan route, and eleven to twenty million (depending on the author) across the Atlantic Ocean.[23]

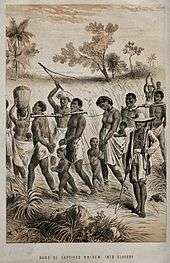

According to John K. Thornton, Europeans usually bought enslaved people who were captured in endemic warfare between African states.[24] Some Africans had made a business out of capturing Africans from neighboring ethnic groups or war captives and selling them.[25] A reminder of this practice is documented in the Slave Trade Debates of England in the early 19th century: "All the old writers ... concur in stating not only that wars are entered into for the sole purpose of making slaves, but that they are fomented by Europeans, with a view to that object."[26] People living around the Niger River were transported from these markets to the coast and sold at European trading ports in exchange for muskets and manufactured goods such as cloth or alcohol.[27] However, the European demand for slaves provided a large new market for the already existing trade.[28] While those held in slavery in their own region of Africa might hope to escape, those shipped away had little chance of returning to Africa.

European colonization and slavery in West Africa

Upon discovering new lands through their naval explorations, European colonisers soon began to migrate to and settle in lands outside their native continent. Off the coast of Africa, European migrants, under the directions of the Kingdom of Castile, invaded and colonised the Canary Islands during the 15th century, where they converted much of the land to the production of wine and sugar. Along with this, they also captured native Canary Islanders, the Guanches, to use as slaves both on the Islands and across the Christian Mediterranean.[29]

As historian John Thornton remarked, "the actual motivation for European expansion and for navigational breakthroughs was little more than to exploit the opportunity for immediate profits made by raiding and the seizure or purchase of trade commodities".[30] Using the Canary Islands as a naval base, Europeans, at the time primarily Portuguese traders, began to move their activities down the western coast of Africa, performing raids in which slaves would be captured to be later sold in the Mediterranean.[31] Although initially successful in this venture, "it was not long before African naval forces were alerted to the new dangers, and the Portuguese [raiding] ships began to meet strong and effective resistance", with the crews of several of them being killed by African sailors, whose boats were better equipped at traversing the west African coasts and river systems.[32]

By 1494, the Portuguese king had entered agreements with the rulers of several West African states that would allow trade between their respective peoples, enabling the Portuguese to "tap into" the "well-developed commercial economy in Africa ... without engaging in hostilities".[33] "Peaceful trade became the rule all along the African coast", although there were some rare exceptions when acts of aggression led to violence. For instance, Portuguese traders attempted to conquer the Bissagos Islands in 1535.[34] In 1571 Portugal, supported by the Kingdom of Kongo, took control of the south-western region of Angola in order to secure its threatened economic interest in the area. Although Kongo later joined a coalition in 1591 to force the Portuguese out, Portugal had secured a foothold on the continent that it continued to occupy until the 20th century.[35] Despite these incidences of occasional violence between African and European forces, many African states ensured that any trade went on in their own terms, for instance, imposing custom duties on foreign ships. In 1525, the Kongolese king Afonso I seized a French vessel and its crew for illegally trading on his coast.[34]

Historians have widely debated the nature of the relationship between these African kingdoms and the European traders. The Guyanese historian Walter Rodney (1972) has argued that it was an unequal relationship, with Africans being forced into a "colonial" trade with the more economically developed Europeans, exchanging raw materials and human resources (i.e. slaves) for manufactured goods. He argued that it was this economic trade agreement dating back to the 16th century that led to Africa being underdeveloped in his own time.[36] These ideas were supported by other historians, including Ralph Austen (1987).[37] This idea of an unequal relationship was contested by John Thornton (1998), who argued that "the Atlantic slave trade was not nearly as critical to the African economy as these scholars believed" and that "African manufacturing [at this period] was more than capable of handling competition from preindustrial Europe".[38] However, Anne Bailey, commenting on Thornton's suggestion that Africans and Europeans were equal partners in the Atlantic slave trade, wrote:

[T]o see Africans as partners implies equal terms and equal influence on the global and intercontinental processes of the trade. Africans had great influence on the continent itself, but they had no direct influence on the engines behind the trade in the capital firms, the shipping and insurance companies of Europe and America, or the plantation systems in Americas. They did not wield any influence on the building manufacturing centers of the West.[39]

16th, 17th and 18th centuries

The Atlantic slave trade is customarily divided into two eras, known as the First and Second Atlantic Systems.

The First Atlantic system was the trade of enslaved Africans to, primarily, South American colonies of the Portuguese and Spanish empires; it accounted for slightly more than 3% of all Atlantic slave trade. It started (on a significant scale) in about 1502[40] and lasted until 1580 when Portugal was temporarily united with Spain. While the Portuguese were directly involved in trading enslaved peoples, the Spanish empire relied on the asiento system, awarding merchants (mostly from other countries) the license to trade enslaved people to their colonies. During the first Atlantic system, most of these traders were Portuguese, giving them a near-monopoly during the era. Some Dutch, English, and French traders also participated in the slave trade.[41] After the union, Portugal came under Spanish legislation that prohibited it from directly engaging in the slave trade as a carrier. It became a target for the traditional enemies of Spain, losing a large share of the trade to the Dutch, English, and French.

The Second Atlantic system was the trade of enslaved Africans by mostly English, Portuguese, French and Dutch traders. The main destinations of this phase were the Caribbean colonies and Brazil, as European nations built up economically slave-dependent colonies in the New World.[42] Slightly more than 3% of the enslaved people exported from Africa were traded between 1450 and 1600, and 16% in the 17th century.

.jpg)

It is estimated that more than half of the entire slave trade took place during the 18th century, with the British, Portuguese and French being the main carriers of nine out of ten slaves abducted in Africa.[43] By the 1690s, the English were shipping the most slaves from West Africa.[44] They maintained this position during the 18th century, becoming the biggest shippers of slaves across the Atlantic.[45][8] By the 18th century, Angola had become one of the principal sources of the Atlantic slave trade.[46]

Following the British and United States' bans on the African slave trade in 1808, it declined, but the period after still accounted for 28.5% of the total volume of the Atlantic slave trade.[47] Between 1810 and 1860, over 3.5 million slaves were transported, with 850,000 in the 1820s.[8]:193

A burial ground in Campeche, Mexico, suggests slaves had been brought there not long after Hernán Cortés completed the subjugation of Aztec and Mayan Mexico in the 16th century. The graveyard had been in use from approximately 1550 to the late 17th century.[48]

Triangular trade

The first side of the triangle was the export of goods from Europe to Africa. A number of African kings and merchants took part in the trading of enslaved people from 1440 to about 1833. For each captive, the African rulers would receive a variety of goods from Europe. These included guns, ammunition, and other factory-made goods. The second leg of the triangle exported enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas and the Caribbean Islands. The third and final part of the triangle was the return of goods to Europe from the Americas. The goods were the products of slave-labour plantations and included cotton, sugar, tobacco, molasses and rum.[49] Sir John Hawkins, considered the pioneer of the British slave trade, was the first to run the Triangular trade, making a profit at every stop.

Labour and slavery

.jpg)

The Atlantic slave trade was the result of, among other things, labour shortage, itself in turn created by the desire of European colonists to exploit New World land and resources for capital profits. Native peoples were at first utilized as slave labour by Europeans until a large number died from overwork and Old World diseases.[50] Alternative sources of labour, such as indentured servitude, failed to provide a sufficient workforce. Many crops could not be sold for profit, or even grown, in Europe. Exporting crops and goods from the New World to Europe often proved to be more profitable than producing them on the European mainland. A vast amount of labour was needed to create and sustain plantations that required intensive labour to grow, harvest, and process prized tropical crops. Western Africa (part of which became known as "the Slave Coast"), Angola and nearby Kingdoms and later Central Africa, became the source for enslaved people to meet the demand for labour.[51]

The basic reason for the constant shortage of labour was that, with much cheap land available and many landowners searching for workers, free European immigrants were able to become landowners themselves relatively quickly, thus increasing the need for workers.[52]

Thomas Jefferson attributed the use of slave labour in part to the climate, and the consequent idle leisure afforded by slave labour: "For in a warm climate, no man will labour for himself who can make another labour for him. This is so true, that of the proprietors of slaves a very small proportion indeed are ever seen to labour."[53] In a 2015 paper, economist Elena Esposito argued that the enslavement of Africans in colonial America was attributable to the fact that the American south was sufficiently warm and humid for malaria to thrive; the disease had debilitating effects on the European settlers. Conversely, many enslaved Africans were taken from regions of Africa which hosted particularly potent strains of the disease, so the Africans had already developed natural resistance to malaria. This, Esposito argued, resulted in higher malaria survival rates in the American south among enslaved Africans than among European labourers, making them a more profitable source of labour and encouraging their use.[54]

African participation in the slave trade

Africans played a direct role in the slave trade, selling their captives or prisoners of war to European buyers.[22] The prisoners and captives who were sold were usually from neighbouring or enemy ethnic groups. These captive slaves were considered "other", not part of the people of the ethnic group or "tribe"; African kings held no particular loyalty to them. Sometimes criminals would be sold so that they could no longer commit crimes in that area. Most other slaves were obtained from kidnappings, or through raids that occurred at gunpoint through joint ventures with the Europeans.[22] But some African kings refused to sell any of their captives or criminals. King Jaja of Opobo, a former slave, refused to do any business with the slavers.

According to Ipsen, Africans, namely Ghana, also participated in the slave trade through intermarriage, or cassare, meaning "to set up house". It is derived from the Portuguese word "casar", meaning "to marry". Cassare created political and economic bonds between European and African slave traders. Cassare was a pre-European practice used to integrate the "other" from a differing African tribe. Powerful West African groups used these marriages as an alliance used to strengthen their trade networks with European men by marrying off African women from families with ties to the slave trade. Early on in the Atlantic Slave trade, these marriages were common. The marriages were even performed using African customs, which Europeans did not object to, seeing how important the connections were.[55]

European participation in the slave trade

Although Europeans were the market for slaves, Europeans rarely entered the interior of Africa, due to fear of disease and fierce African resistance.[56] In Africa, convicted criminals could be punished by enslavement, a punishment which became more prevalent as slavery became more lucrative. Since most of these nations did not have a prison system, convicts were often sold or used in the scattered local domestic slave market.

In 1778, Thomas Kitchin estimated that Europeans were bringing an estimated 52,000 slaves to the Caribbean yearly, with the French bringing the most Africans to the French West Indies (13,000 out of the yearly estimate).[57] The Atlantic slave trade peaked in the last two decades of the 18th century,[58] during and following the Kongo Civil War.[59] Wars among tiny states along the Niger River's Igbo-inhabited region and the accompanying banditry also spiked in this period.[25] Another reason for surplus supply of enslaved people was major warfare conducted by expanding states, such as the kingdom of Dahomey,[60] the Oyo Empire, and the Asante Empire.[61]

Slavery in Africa and the New World contrasted

Forms of slavery varied both in Africa and in the New World. In general, slavery in Africa was not heritable—that is, the children of slaves were free—while in the Americas, children of slave mothers were considered born into slavery. This was connected to another distinction: slavery in West Africa was not reserved for racial or religious minorities, as it was in European colonies, although the case was otherwise in places such as Somalia, where Bantus were taken as slaves for the ethnic Somalis.[62][63]

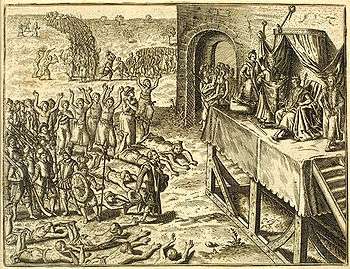

The treatment of slaves in Africa was more variable than in the Americas. At one extreme, the kings of Dahomey routinely slaughtered slaves in hundreds or thousands in sacrificial rituals, and slaves as human sacrifices were also known in Cameroon.[64] On the other hand, slaves in other places were often treated as part of the family, "adopted children", with significant rights including the right to marry without their masters' permission.[65] Scottish explorer Mungo Park wrote:

The slaves in Africa, I suppose, are nearly in the proportion of three to one to the freemen. They claim no reward for their services except food and clothing, and are treated with kindness or severity, according to the good or bad disposition of their masters ... The slaves which are thus brought from the interior may be divided into two distinct classes—first, such as were slaves from their birth, having been born of enslaved mothers; secondly, such as were born free, but who afterwards, by whatever means, became slaves. Those of the first description are by far the most numerous ...[66]

In the Americas, slaves were denied the right to marry freely and masters did not generally accept them as equal members of the family. New World slaves were considered the property of their owners, and slaves convicted of revolt or murder were executed.[67]

Slave market regions and participation

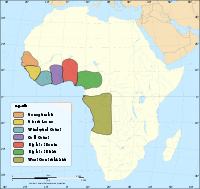

There were eight principal areas used by Europeans to buy and ship slaves to the Western Hemisphere. The number of enslaved people sold to the New World varied throughout the slave trade. As for the distribution of slaves from regions of activity, certain areas produced far more enslaved people than others. Between 1650 and 1900, 10.2 million enslaved Africans arrived in the Americas from the following regions in the following proportions:[68]

- Senegambia (Senegal and the Gambia): 4.8%

- Upper Guinea (Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Sierra Leone): 4.1%

- Windward Coast (Liberia and Ivory Coast): 1.8%

- Gold Coast (Ghana and east of Ivory Coast): 10.4%

- Bight of Benin (Togo, Benin and Nigeria west of the Niger Delta): 20.2%

- Bight of Biafra (Nigeria east of the Niger Delta, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon): 14.6%

- West Central Africa (Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola): 39.4%

- Southeastern Africa (Mozambique and Madagascar): 4.7%

Although the slave trade was largely global, there was considerable intracontinental slave trade in which 8 million people were enslaved within the African continent.[69] Of those who did move out of Africa, 8 million were forced out of Eastern Africa to be sent to Asia.[69]

African kingdoms of the era

There were over 173 city-states and kingdoms in the African regions affected by the slave trade between 1502 and 1853, when Brazil became the last Atlantic import nation to outlaw the slave trade. Of those 173, no fewer than 68 could be deemed nation states with political and military infrastructures that enabled them to dominate their neighbours. Nearly every present-day nation had a pre-colonial predecessor, sometimes an African empire with which European traders had to barter.

Ethnic groups

The different ethnic groups brought to the Americas closely correspond to the regions of heaviest activity in the slave trade. Over 45 distinct ethnic groups were taken to the Americas during the trade. Of the 45, the ten most prominent, according to slave documentation of the era are listed below.[70]

- The BaKongo of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola

- The Mandé of Upper Guinea

- The Gbe speakers of Togo, Ghana, and Benin (Adja, Mina, Ewe, Fon)

- The Akan of Ghana and Ivory Coast

- The Wolof of Senegal and the Gambia

- The Igbo of southeastern Nigeria

- The Mbundu of Angola (includes both Ambundu and Ovimbundu)

- The Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria

- The Chamba of Cameroon

- The Makua of Mozambique

Human toll

The transatlantic slave trade resulted in a vast and as yet still unknown loss of life for African captives both in and outside the Americas. Approximately 1.2–2.4 million Africans died during their transport to the New World.[71] More died soon after their arrival. The number of lives lost in the procurement of slaves remains a mystery but may equal or exceed the number who survived to be enslaved.[10]

The savage nature of the trade led to the destruction of individuals and cultures. The following figures do not include deaths of enslaved Africans as a result of their labour, slave revolts, or diseases suffered while living among New World populations. Historian Ana Lucia Araujo has noted that the process of enslavement did not end with arrival Western Hemisphere shores; the different paths taken by the individuals and groups who were victims of the Atlantic slave trade were influenced by different factors—including the disembarking region, the kind of work performed, gender, age, religion, and language.[72]

Patrick Manning estimates that about 12 million slaves entered the Atlantic trade between the 16th and 19th century, but about 1.5 million died on board ship. About 10.5 million slaves arrived in the Americas. Besides the slaves who died on the Middle Passage, more Africans likely died during the slave raids in Africa and forced marches to ports. Manning estimates that 4 million died inside Africa after capture, and many more died young. Manning's estimate covers the 12 million who were originally destined for the Atlantic, as well as the 6 million destined for Asian slave markets and the 8 million destined for African markets.[9] Of the slaves shipped to The Americas, the largest share went to Brazil and the Caribbean.[73]

African conflicts

According to Kimani Nehusi, the presence of European slavers affected the way in which the legal code in African societies responded to offenders. Crimes traditionally punishable by some other form of punishment became punishable by enslavement and sale to slave traders. According to David Stannard's American Holocaust, 50% of African deaths occurred in Africa as a result of wars between native kingdoms, which produced the majority of slaves.[10] This includes not only those who died in battles but also those who died as a result of forced marches from inland areas to slave ports on the various coasts.[74] The practice of enslaving enemy combatants and their villages was widespread throughout Western and West Central Africa, although wars were rarely started to procure slaves. The slave trade was largely a by-product of tribal and state warfare as a way of removing potential dissidents after victory or financing future wars.[75] However, some African groups proved particularly adept and brutal at the practice of enslaving, such as Oyo, Benin, Igala, Kaabu, Asanteman, Dahomey, the Aro Confederacy and the Imbangala war bands.[76]

In letters written by the Manikongo, Nzinga Mbemba Afonso, to the King João III of Portugal, he writes that Portuguese merchandise flowing in is what is fueling the trade in Africans. He requests the King of Portugal to stop sending merchandise but should only send missionaries. In one of his letters he writes:

Each day the traders are kidnapping our people—children of this country, sons of our nobles and vassals, even people of our own family. This corruption and depravity are so widespread that our land is entirely depopulated. We need in this kingdom only priests and schoolteachers, and no merchandise, unless it is wine and flour for Mass. It is our wish that this Kingdom not be a place for the trade or transport of slaves ... Many of our subjects eagerly lust after Portuguese merchandise that your subjects have brought into our domains. To satisfy this inordinate appetite, they seize many of our black free subjects ... They sell them. After having taken these prisoners [to the coast] secretly or at night ... As soon as the captives are in the hands of white men they are branded with a red-hot iron.[77]

Before the arrival of the Portuguese, slavery had already existed in the Kingdom of Kongo. Afonso I of Kongo believed that the slave trade should be subject to Kongo law. When he suspected the Portuguese of receiving illegally enslaved persons to sell, he wrote to King João III in 1526 imploring him to put a stop to the practice.[78]

The kings of Dahomey sold war captives into transatlantic slavery; they would otherwise have been killed in a ceremony known as the Annual Customs. As one of West Africa's principal slave states, Dahomey became extremely unpopular with neighbouring peoples.[79][80][81] Like the Bambara Empire to the east, the Khasso kingdoms depended heavily on the slave trade for their economy. A family's status was indicated by the number of slaves it owned, leading to wars for the sole purpose of taking more captives. This trade led the Khasso into increasing contact with the European settlements of Africa's west coast, particularly the French.[82] Benin grew increasingly rich during the 16th and 17th centuries on the slave trade with Europe; slaves from enemy states of the interior were sold and carried to the Americas in Dutch and Portuguese ships. The Bight of Benin's shore soon came to be known as the "Slave Coast".[83]

King Gezo of Dahomey said in the 1840s:

The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth ... the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery ...[84]

In 1807, the UK Parliament passed the Bill that abolished the trading of slaves. The King of Bonny (now in Nigeria) was horrified at the conclusion of the practice:

We think this trade must go on. That is the verdict of our oracle and the priests. They say that your country, however great, can never stop a trade ordained by God himself.[85]

Port factories

After being marched to the coast for sale, enslaved people were held in large forts called factories. The amount of time in factories varied, but Milton Meltzer states in Slavery: A World History that around 4.5% of deaths attributed to the transatlantic slave trade occurred during this phase.[86] In other words, over 820,000 people are believed to have died in African ports such as Benguela, Elmina, and Bonny, reducing the number of those shipped to 17.5 million.[86]

Atlantic shipment

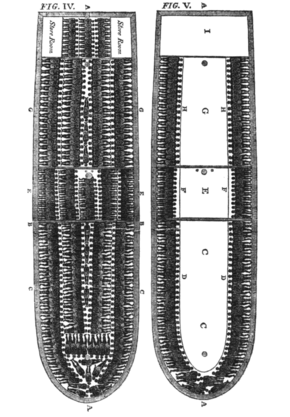

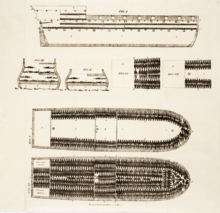

After being captured and held in the factories, slaves entered the infamous Middle Passage. Meltzer's research puts this phase of the slave trade's overall mortality at 12.5%.[86] Their deaths were the result of brutal treatment and poor care from the time of their capture and throughout their voyage.[87] Around 2.2 million Africans died during these voyages, where they were packed into tight, unsanitary spaces on ships for months at a time. Measures were taken to stem the onboard mortality rate, such as enforced "dancing" (as exercise) above deck and the practice of force-feeding enslaved persons who tried to starve themselves.[74] The conditions on board also resulted in the spread of fatal diseases. Other fatalities were suicides, slaves who escaped by jumping overboard.[74] The slave traders would try to fit anywhere from 350 to 600 slaves on one ship. Before the African slave trade was completely banned by participating nations in 1853, 15.3 million enslaved people had arrived in the Americas.

Raymond L. Cohn, an economics professor whose research has focused on economic history and international migration,[88] has researched the mortality rates among Africans during the voyages of the Atlantic slave trade. He found that mortality rates decreased over the history of the slave trade, primarily because the length of time necessary for the voyage was declining. "In the eighteenth century many slave voyages took at least 2½ months. In the nineteenth century, 2 months appears to have been the maximum length of the voyage, and many voyages were far shorter. Fewer slaves died in the Middle Passage over time mainly because the passage was shorter."[89]

Despite the vast profits of slavery, the ordinary sailors on slave ships were badly paid and subject to harsh discipline. Mortality of around 20%, a number similar and sometimes greater than those of the slaves,[90] was expected in a ship's crew during the course of a voyage; this was due to disease, flogging, overwork, or slave uprisings.[91] Disease (malaria or yellow fever) was the most common cause of death among sailors. A high crew mortality rate on the return voyage was in the captain's interests as it reduced the number of sailors who had to be paid on reaching the home port.[92]

The slave trade was hated by many sailors, and those who joined the crews of slave ships often did so through coercion or because they could find no other employment.[93]

Seasoning camps

Meltzer also states that 33% of Africans would have died in the first year at the seasoning camps found throughout the Caribbean.[86] Jamaica held one of the most notorious of these camps. Dysentery was the leading cause of death.[94] Around 5 million Africans died in these camps, reducing the number of survivors to about 10 million.[86]

Diseases

Many diseases, each capable of killing a large minority or even a majority of a new human population, arrived in the Americas before 1492. They include smallpox, malaria, bubonic plague, typhus, influenza, measles, diphtheria, yellow fever, and whooping cough.[95] During the Atlantic slave trade following the discovery of the New World, diseases such as these are recorded as causing mass mortality.[96]

Evolutionary history may also have played a role in resisting the diseases of the slave trade. Compared to African and Europeans, New World populations did not have a history of exposure to diseases such as malaria, and therefore, no genetic resistance had been produced as a result of adaptation through natural selection.[97]

Levels and extent of immunity varies from disease to disease. For smallpox and measles for example, those who survive are equipped with the immunity to combat the disease for the rest of their life in that they cannot contract the disease again. There are also diseases, such as malaria, which do not confer effective lasting immunity.[97]

Smallpox

Epidemics of smallpox were known for causing a significant decrease in the indigenous population of the New World.[98] The effects on survivors included pockmarks on the skin which left deep scars, commonly causing significant disfigurement. Some Europeans, who believed the plague of syphilis in Europe to have come from the Americas, saw smallpox as the European revenge against the Natives.[96] Africans and Europeans, unlike the native population, often had lifelong immunity, because they had often been exposed to minor forms of the illness such as cowpox or variola minor disease in childhood. By the late 16th century there existed some forms of inoculation and variolation in Africa and the Middle East. One practice features Arab traders in Africa "buying-off" the disease in which a cloth that had been previously exposed to the sickness was to be tied to another child's arm to increase immunity. Another practice involved taking pus from a smallpox scab and putting it in the cut of a healthy individual in an attempt to have a mild case of the disease in the future rather than the effects becoming fatal.[98]

European competition

The trade of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic has its origins in the explorations of Portuguese mariners down the coast of West Africa in the 15th century. Before that, contact with African slave markets was made to ransom Portuguese who had been captured by the intense North African Barbary pirate attacks on Portuguese ships and coastal villages, frequently leaving them depopulated.[99] The first Europeans to use enslaved Africans in the New World were the Spaniards, who sought auxiliaries for their conquest expeditions and labourers on islands such as Cuba and Hispaniola. The alarming decline in the native population had spurred the first royal laws protecting them (Laws of Burgos, 1512–13). The first enslaved Africans arrived in Hispaniola in 1501.[100] After Portugal had succeeded in establishing sugar plantations (engenhos) in northern Brazil c. 1545, Portuguese merchants on the West African coast began to supply enslaved Africans to the sugar planters. While at first these planters had relied almost exclusively on the native Tupani for slave labour, after 1570 they began importing Africans, as a series of epidemics had decimated the already destabilized Tupani communities. By 1630, Africans had replaced the Tupani as the largest contingent of labour on Brazilian sugar plantations. This ended the European medieval household tradition of slavery, resulted in Brazil's receiving the most enslaved Africans, and revealed sugar cultivation and processing as the reason that roughly 84% of these Africans were shipped to the New World.

As Britain rose in naval power and settled continental North America and some islands of the West Indies, they became the leading slave traders.[102] At one stage the trade was the monopoly of the Royal Africa Company, operating out of London. But, following the loss of the company's monopoly in 1689,[103] Bristol and Liverpool merchants became increasingly involved in the trade.[104] By the late 17th century, one out of every four ships that left Liverpool harbour was a slave trading ship.[105] Much of the wealth on which the city of Manchester, and surrounding towns, was built in the late 18th century, and for much of the 19th century, was based on the processing of slave-picked cotton and manufacture of cloth.[106] Other British cities also profited from the slave trade. Birmingham, the largest gun-producing town in Britain at the time, supplied guns to be traded for slaves.[107] 75% of all sugar produced in the plantations was sent to London, and much of it was consumed in the highly lucrative coffee houses there.[105]

New World destinations

The first slaves to arrive as part of a labour force in the New World reached the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in 1502. Cuba received its first four slaves in 1513. Jamaica received its first shipment of 4000 slaves in 1518.[108] Slave exports to Honduras and Guatemala started in 1526.

The first enslaved Africans to reach what would become the United States arrived in July 1526 as part of a Spanish attempt to colonize San Miguel de Gualdape. By November the 300 Spanish colonists were reduced to 100, and their slaves from 100 to 70. The enslaved people revolted in 1526 and joined a nearby Native American tribe, while the Spanish abandoned the colony altogether (1527). The area of the future Colombia received its first enslaved people in 1533. El Salvador, Costa Rica and Florida began their stints in the slave trade in 1541, 1563 and 1581, respectively.

The 17th century saw an increase in shipments. Africans were brought to Point Comfort – several miles downriver from the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia – in 1619. The first kidnapped Africans in English North America were classed as indentured servants and freed after seven years. Virginia law codified chattel slavery in 1656, and in 1662 the colony adopted the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, which classified children of slave mothers as slaves, regardless of paternity. Irish immigrants took slaves to Montserrat in 1651, and in 1655 slaves were shipped to Belize.

By 1802, Russian colonists noted that "Boston" (U.S.-based) skippers were trading African slaves for otter pelts with the Tlingit people in Southeast Alaska.[109]

| Destination | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Portuguese America | 38.5% |

| British West Indies | 18.4% |

| Spanish Empire | 17.5% |

| French Americas | 13.6% |

| British Atlantic Colonies / United States | 9.7% |

| Dutch West Indies | 2.0% |

| Danish West Indies | 0.3% |

| Note: The number of the Africans who arrived in each region is calculated from the total number of slaves imported, about 10,000,000.[111]*Includes British Guiana and British Honduras | |

Punishing slaves at Calabouco, in Rio de Janeiro, c. 1822

Punishing slaves at Calabouco, in Rio de Janeiro, c. 1822 Recently bought slaves in Brazil on their way to the farms of the landowners who bought them c. 1830.

Recently bought slaves in Brazil on their way to the farms of the landowners who bought them c. 1830. A 19th-century lithograph showing a sugarcane plantation in Suriname.

A 19th-century lithograph showing a sugarcane plantation in Suriname.

Economics of slavery

In France in the 18th century, returns for investors in plantations averaged around 6%; as compared to 5% for most domestic alternatives, this represented a 20% profit advantage. Risks—maritime and commercial—were important for individual voyages. Investors mitigated it by buying small shares of many ships at the same time. In that way, they were able to diversify a large part of the risk away. Between voyages, ship shares could be freely sold and bought.[112]

By far the most financially profitable West Indian colonies in 1800 belonged to the United Kingdom. After entering the sugar colony business late, British naval supremacy and control over key islands such as Jamaica, Trinidad, the Leeward Islands and Barbados and the territory of British Guiana gave it an important edge over all competitors; while many British did not make gains, a handful of individuals made small fortunes. This advantage was reinforced when France lost its most important colony, St. Domingue (western Hispaniola, now Haiti), to a slave revolt in 1791[113] and supported revolts against its rival Britain, in the name of liberty after the 1793 French revolution. Before 1791, British sugar had to be protected to compete against cheaper French sugar.

After 1791, the British islands produced the most sugar, and the British people quickly became the largest consumers. West Indian sugar became ubiquitous as an additive to Indian tea. It has been estimated that the profits of the slave trade and of West Indian plantations created up to one-in-twenty of every pound circulating in the British economy at the time of the Industrial Revolution in the latter half of the 18th century.[114]

Effects

|

|

Historian Walter Rodney has argued that at the start of the slave trade in the 16th century, although there was a technological gap between Europe and Africa, it was not very substantial. Both continents were using Iron Age technology. The major advantage that Europe had was in ship building. During the period of slavery, the populations of Europe and the Americas grew exponentially, while the population of Africa remained stagnant. Rodney contended that the profits from slavery were used to fund economic growth and technological advancement in Europe and the Americas. Based on earlier theories by Eric Williams, he asserted that the industrial revolution was at least in part funded by agricultural profits from the Americas. He cited examples such as the invention of the steam engine by James Watt, which was funded by plantation owners from the Caribbean.[116]

Other historians have attacked both Rodney's methodology and accuracy. Joseph C. Miller has argued that the social change and demographic stagnation (which he researched on the example of West Central Africa) was caused primarily by domestic factors. Joseph Inikori provided a new line of argument, estimating counterfactual demographic developments in case the Atlantic slave trade had not existed. Patrick Manning has shown that the slave trade did have a profound impact on African demographics and social institutions, but criticized Inikori's approach for not taking other factors (such as famine and drought) into account, and thus being highly speculative.[117]

Effect on the economy of West Africa

No scholars dispute the harm done to the enslaved people but the effect of the trade on African societies is much debated, due to the apparent influx of goods to Africans. Proponents of the slave trade, such as Archibald Dalzel, argued that African societies were robust and not much affected by the trade. In the 19th century, European abolitionists, most prominently Dr. David Livingstone, took the opposite view, arguing that the fragile local economy and societies were being severely harmed by the trade.

Because the negative effects of slavery on the economies of Africa have been well documented, namely the significant decline in population, some African rulers likely saw an economic benefit from trading their subjects with European slave traders. With the exception of Portuguese-controlled Angola, coastal African leaders "generally controlled access to their coasts, and were able to prevent direct enslavement of their subjects and citizens".[118] Thus, as African scholar John Thornton argues, African leaders who allowed the continuation of the slave trade likely derived an economic benefit from selling their subjects to Europeans. The Kingdom of Benin, for instance, participated in the African slave trade, at will, from 1715 to 1735, surprising Dutch traders, who had not expected to buy slaves in Benin.[118] The benefit derived from trading slaves for European goods was enough to make the Kingdom of Benin rejoin the trans-Atlantic slave trade after centuries of non-participation. Such benefits included military technology (specifically guns and gunpowder), gold, or simply maintaining amicable trade relationships with European nations. The slave trade was, therefore, a means for some African elites to gain economic advantages.[119] Historian Walter Rodney estimates that by c.1770, the King of Dahomey was earning an estimated £250,000 per year by selling captive African soldiers and enslaved people to the European slave-traders. Many West African countries also already had a tradition of holding slaves, which was expanded into trade with Europeans.

The Atlantic trade brought new crops to Africa and also more efficient currencies which were adopted by the West African merchants. This can be interpreted as an institutional reform which reduced the cost of doing business. But the developmental benefits were limited as long as the business including slaving.[120]

Both Thornton and Fage contend that while African political elite may have ultimately benefited from the slave trade, their decision to participate may have been influenced more by what they could lose by not participating. In Fage's article "Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Context of West African History", he notes that for West Africans "... there were really few effective means of mobilizing labour for the economic and political needs of the state" without the slave trade.[119]

Effects on the British economy

Historian Eric Williams in 1944 argued that the profits that Britain received from its sugar colonies, or from the slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean, contributed to the financing of Britain's industrial revolution. However, he says that by the time of the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, and the emancipation of the slaves in 1833, the sugar plantations of the British West Indies had lost their profitability, and it was in Britain's economic interest to emancipate the slaves.[121]

Other researchers and historians have strongly contested what has come to be referred to as the "Williams thesis" in academia. David Richardson has concluded that the profits from the slave trade amounted to less than 1% of domestic investment in Britain.[122] Economic historian Stanley Engerman finds that even without subtracting the associated costs of the slave trade (e.g., shipping costs, slave mortality, mortality of British people in Africa, defense costs) or reinvestment of profits back into the slave trade, the total profits from the slave trade and of West Indian plantations amounted to less than 5% of the British economy during any year of the Industrial Revolution.[123] Engerman's 5% figure gives as much as possible in terms of benefit of the doubt to the Williams argument, not solely because it does not take into account the associated costs of the slave trade to Britain, but also because it carries the full-employment assumption from economics and holds the gross value of slave trade profits as a direct contribution to Britain's national income.[123] Historian Richard Pares, in an article written before Williams' book, dismisses the influence of wealth generated from the West Indian plantations upon the financing of the Industrial Revolution, stating that whatever substantial flow of investment from West Indian profits into industry there occurred after emancipation, not before. However, each of these works focus primarily on the slave trade or the Industrial Revolution, and not the main body of the Williams thesis, which was on sugar and slavery itself. Therefore, they do not refute the main body of the Williams thesis.[124][125]

Seymour Drescher and Robert Anstey argue the slave trade remained profitable until the end, and that moralistic reform, not economic incentive, was primarily responsible for abolition. They say slavery remained profitable in the 1830s because of innovations in agriculture. However, Drescher's Econocide wraps up its study in 1823, and does not address the majority of the Williams thesis, which covers the decline of the sugar plantations after 1823, the emancipation of the slaves in the 1830s, and the subsequent abolition of sugar duties in the 1840s. These arguments do not refute the main body of the Williams thesis, which presents economic data to show that the slave trade was minor compared to the wealth generated by sugar and slavery itself in the British Caribbean.[126][125][127]

Karl Marx in his influential economic history of capitalism Das Kapital wrote that "... the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signaled the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production". He argued that the slave trade was part of what he termed the "primitive accumulation" of capital, the 'non-capitalist' accumulation of wealth that preceded and created the financial conditions for Britain's industrialisation.[128]

Demographics

The demographic effects of the slave trade is a controversial and highly debated issue. Although scholars such as Paul Adams and Erick D. Langer have estimated that sub-Saharan Africa represented about 18 percent of the world's population in 1600 and only 6 percent in 1900,[129] the reasons for this demographic shift have been the subject of much debate. In addition to the depopulation Africa experienced because of the slave trade, African nations were left with severely imbalanced gender ratios, with females comprising up to 65 percent of the population in hard-hit areas such as Angola.[69] Moreover, many scholars (such as Barbara N. Ramusack) have suggested a link between the prevalence of prostitution in Africa today with the temporary marriages that were enforced during the course of the slave trade.[130]

Walter Rodney argued that the export of so many people had been a demographic disaster which left Africa permanently disadvantaged when compared to other parts of the world, and it largely explains the continent's continued poverty.[116] He presented numbers showing that Africa's population stagnated during this period, while those of Europe and Asia grew dramatically. According to Rodney, all other areas of the economy were disrupted by the slave trade as the top merchants abandoned traditional industries in order to pursue slaving, and the lower levels of the population were disrupted by the slaving itself.

Others have challenged this view. J. D. Fage compared the demographic effect on the continent as a whole. David Eltis has compared the numbers to the rate of emigration from Europe during this period. In the 19th century alone over 50 million people left Europe for the Americas, a far higher rate than were ever taken from Africa.[131]

Other scholars accused Walter Rodney of mischaracterizing the trade between Africans and Europeans. They argue that Africans, or more accurately African elites, deliberately let European traders join in an already large trade in enslaved people and that they were not patronized.[132]

As Joseph E. Inikori argues, the history of the region shows that the effects were still quite deleterious. He argues that the African economic model of the period was very different from the European model, and could not sustain such population losses. Population reductions in certain areas also led to widespread problems. Inikori also notes that after the suppression of the slave trade Africa's population almost immediately began to rapidly increase, even prior to the introduction of modern medicines.[133]

Legacy of racism

Walter Rodney states

The role of slavery in promoting racist prejudice and ideology has been carefully studied in certain situations, especially in the USA. The simple fact is that no people can enslave another for four centuries without coming out with a notion of superiority, and when the colour and other physical traits of those peoples were quite different it was inevitable that the prejudice should take a racist form.[116]

Eric Williams argued that "A racial twist [was] given to what is basically an economic phenomenon. Slavery was not born of racism: rather, racism was the consequence of slavery."[134]

Similarly, John Darwin writes "The rapid conversion from white indentured labour to black slavery... made the English Caribbean a frontier of civility where English (later British) ideas about race and slave labour were ruthlessly adapted to local self-interest...Indeed, the root justification for the system of slavery and the savage apparatus of coercion on which its preservation depended was the ineradicable barbarism of the slave population, a product, it was argued, of its African origins".[135]

End of the Atlantic slave trade

In Britain, America, Portugal and in parts of Europe, opposition developed against the slave trade. Davis says that abolitionists assumed "that an end to slave imports would lead automatically to the amelioration and gradual abolition of slavery".[136] In Britain and America, opposition to the trade was led by the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and establishment Evangelicals such as William Wilberforce. Many people joined the movement and they began to protest against the trade, but they were opposed by the owners of the colonial holdings.[137] Following Lord Mansfield's decision in 1772, many abolitionists and slave-holders believed that slaves became free upon entering the British isles.[138] However, in reality slavery continued in Britain right up to abolition in the 1830s. The Mansfield ruling on Somerset v Stewart only decreed that a slave could not be transported out of England against his will.[139]

Under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson, the new state of Virginia in 1778 became the first state and one of the first jurisdictions anywhere to stop the importation of slaves for sale; it made it a crime for traders to bring in slaves from out of state or from overseas for sale; migrants from other states were allowed to bring their own slaves. The new law freed all slaves brought in illegally after its passage and imposed heavy fines on violators.[140][141][142] All the other states followed suit, although South Carolina reopened the slave trade in 1803.[143]

Denmark, which had been active in the slave trade, was the first country to ban the trade through legislation in 1792, which took effect in 1803.[144] Britain banned the slave trade in 1807, imposing stiff fines for any slave found aboard a British ship (see Slave Trade Act 1807). The Royal Navy moved to stop other nations from continuing the slave trade and declared that slaving was equal to piracy and was punishable by death. The United States Congress passed the Slave Trade Act of 1794, which prohibited the building or outfitting of ships in the U.S. for use in the slave trade. The U.S. Constitution barred a federal prohibition on importing slaves for 20 years; at that time the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves prohibited imports on the first day the Constitution permitted: January 1, 1808.

British abolitionism

William Wilberforce was a driving force in the British Parliament in the fight against the slave trade in the British Empire. The British abolitionists focused on the slave trade, arguing that the trade was not necessary for the economic success of sugar on the British West Indian colonies. This argument was accepted by wavering politicians, who did not want to destroy the valuable and important sugar colonies of the British Caribbean. The British parliament was also concerned about the success of the Haitian Revolution, and they believed they had to abolish the trade to prevent a similar conflagration from occurring in a British Caribbean colony.[145]

On 22 February 1807, the House of Commons passed a motion 283 votes to 16 to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. Hence, the slave trade was abolished, but not the still-economically viable institution of slavery itself, which provided Britain's most lucrative import at the time, sugar. Abolitionists did not move against sugar and slavery itself until after the sugar industry went into terminal decline after 1823.[146]

At the same time, although without mutual consultation, the United States abolished the slave trade the same year, but not its internal slave trade which became the dominant character in American slavery until the 1860s.[147] In 1805 the British Order-in-Council had restricted the importation of slaves into colonies that had been captured from France and the Netherlands.[138] Britain continued to press other nations to end its trade; in 1810 an Anglo-Portuguese treaty was signed whereby Portugal agreed to restrict its trade into its colonies; an 1813 Anglo-Swedish treaty whereby Sweden outlawed its slave trade; the Treaty of Paris 1814 where France agreed with Britain that the trade is "repugnant to the principles of natural justice" and agreed to abolish the slave trade in five years; the 1814 Anglo-Netherlands treaty where the Dutch outlawed its slave trade.[138]

Castlereagh and Palmerston's diplomacy

Abolitionist opinion in Britain was strong enough in 1807 to abolish the slave trade in all British possessions, although slavery itself persisted in the colonies until 1833.[148] Abolitionists after 1807 focused on international agreements to abolish the slave trade. Foreign Minister Castlereagh switched his position and became a strong supporter of the movement. Britain arrange treaties with Portugal Sweden and Denmark, 1810–1814, whereby they agreed to end or restrict their trading. These were preliminary to the Congress of Vienna negotiations that Castlereagh dominated and which resulted in a general declaration condemning the slave trade.[149] The problem was that the treaties and declarations were hard to enforce, given the very high profits available to private interests. As Foreign Minister, Castlereagh cooperated with senior officials to use the Royal Navy to detect and capture slave ships. He used diplomacy to make search and seize agreements with all the government whose ships were trading. There was serious friction with the United States, where the southern slave interest was politically powerful. Washington recoiled at British policing of the high seas. Spain France and Portugal also relied on the international slave trade to supply their colonial plantations. As more and more diplomatic arrangements were made by Castlereagh, the owners of slave ships started flying false flags of nations that had not agreed, especially the United States. It was illegal under American law for American ships to engage in the slave trade, but the idea of Britain enforcing American laws was unacceptable to Washington. Lord Palmerston and other British foreign ministers continued the Castlereagh policies. Eventually, in 1842 in 1845, an arrangement was reached between London and Washington. With the arrival of a staunchly anti-slavery government in Washington in 1861, the Atlantic slave trade was doomed. In the long run, Castlereagh's strategy on how to stifle the slave trade proved successful.[150]

Prime Minister Palmerston detested slavery, and in Nigeria in 1851 he took advantage of divisions in native politics, the presence of Christian missionaries, and the maneuvers of British consul John Beecroft to encourage the overthrow of King Kosoko. The new King Akitoye was a docile nonslave-trading puppet.[151]

British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron, established in 1808, grew by 1850 to a force of some 25 vessels, which were tasked with combating slavery along the African coast.[152] Between 1807 and 1860, the Royal Navy's Squadron seized approximately 1,600 ships involved in the slave trade and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard these vessels.[153] Several hundred slaves a year were transported by the navy to the British colony of Sierra Leone, where they were made to serve as "apprentices" in the colonial economy until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.[154]

.jpg)

Last slave ship to the United States

The last recorded slave ship to land on U.S. soil was the Clotilde, which in 1859 illegally smuggled a number of Africans into the town of Mobile, Alabama.[156] The Africans on board were sold as slaves; however, slavery in the U.S. was abolished five years later following the end of the American Civil War in 1865. Cudjoe Lewis, who died in 1935, was long believed to be the last survivor of the Clotilde and the last surviving slave brought from Africa to the United States [157] but recent research has found that two other survivors from the Clotilde outlived him, Redoshi (who died in 1937) and Matilda McCrear (who died in 1940).[158][159] The last country to ban the Atlantic slave trade was Brazil in 1831. However, a vibrant illegal trade continued to ship large numbers of enslaved people to Brazil and also to Cuba until the 1860s, when British enforcement and further diplomacy finally ended the Atlantic slave trade. In 1870, Portugal ended the last trade route with the Americas, where the last country to import slaves was Brazil. In Brazil, however, slavery itself was not ended until 1888, making it the last country in the Americas to end involuntary servitude.

Economic motivation to end the slave trade

The historian Walter Rodney contends that it was a decline in the profitability of the triangular trades that made it possible for certain basic human sentiments to be asserted at the decision-making level in a number of European countries—Britain being the most crucial because it was the greatest carrier of African captives across the Atlantic. Rodney states that changes in productivity, technology, and patterns of exchange in Europe and the Americas informed the decision by the British to end their participation in the trade in 1807. In 1809 President James Madison outlawed the slave trade with the United States.

Nevertheless, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri[160] argue that it was neither a strictly economic nor moral matter. First, because slavery was (in practice) still beneficial to capitalism, providing not only an influx of capital but also disciplining hardship into workers (a form of "apprenticeship" to the capitalist industrial plant). The more "recent" argument of a "moral shift" (the basis of the previous lines of this article) is described by Hardt and Negri as an "ideological" apparatus in order to eliminate the sentiment of guilt in western society. Although moral arguments did play a secondary role, they usually had major resonance when used as a strategy to undercut competitors' profits. This argument holds that Eurocentric history has been blind to the most important element in this fight for emancipation, precisely, the constant revolt and the antagonism of slaves' revolts. The most important of those being the Haitian Revolution. The shock of this revolution in 1804, certainly introduces an essential political argument into the end of the slave trade, which happened only three years later.

However, both James Stephen (British politician) and Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux wrote that the slave trade could be abolished for the benefit of the British colonies, and the latter's pamphlet was often used in parliamentary debates in favour of abolition. William Pitt the Younger argued on the basis of these writings that the British colonies would be better off, in economics as well as security, if the trade was abolished. As a result, according to historian Christer Petley, abolitionists argued, and even some absentee plantation owners accepted, that the trade could be abolished "without substantial damage to the plantation economy". William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville argued that "the slave population of the colonies could be maintained without it." Petley points out that government took the decision to abolish the trade "with the express intention of improving, not destroying, the still-lucrative plantation economy of the British West Indies."[161]

Legacy

African diaspora

The African diaspora which was created via slavery has been a complex interwoven part of American history and culture.[162] In the United States, the success of Alex Haley's book Roots: The Saga of an American Family, published in 1976, and Roots, the subsequent television miniseries based upon it, broadcast on the ABC network in January 1977, led to an increased interest and appreciation of African heritage amongst the African-American community.[163] The influence of these led many African Americans to begin researching their family histories and making visits to West Africa. In turn, a tourist industry grew up to supply them. One notable example of this is through the Roots Homecoming Festival held annually in the Gambia, in which rituals are held through which African Americans can symbolically "come home" to Africa.[164] Issues of dispute have however developed between African Americans and African authorities over how to display historic sites that were involved in the Atlantic slave trade, with prominent voices in the former criticising the latter for not displaying such sites sensitively, but instead treating them as a commercial enterprise.[165]

"Back to Africa"

In 1816, a group of wealthy European-Americans, some of whom were abolitionists and others who were racial segregationists, founded the American Colonization Society with the express desire of sending African Americans who were in the United States to West Africa. In 1820, they sent their first ship to Liberia, and within a decade around two thousand African Americans had been settled there. Such re-settlement continued throughout the 19th century, increasing following the deterioration of race relations in the Southern states of the US following Reconstruction in 1877.[166]

Rastafari movement

The Rastafari movement, which originated in Jamaica, where 92% of the population are descended from the Atlantic slave trade, has made efforts to publicize the slavery and to ensure it is not forgotten, especially through reggae music.[167]

Apologies

Worldwide

In 1998, UNESCO designated 23 August as International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. Since then there have been a number of events recognizing the effects of slavery.

At the 2001 World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa, African nations demanded a clear apology for slavery from the former slave-trading countries. Some nations were ready to express an apology, but the opposition, mainly from the United Kingdom, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, and the United States blocked attempts to do so. A fear of monetary compensation might have been one of the reasons for the opposition. As of 2009, efforts are underway to create a UN Slavery Memorial as a permanent remembrance of the victims of the Atlantic slave trade.

Benin

In 1999, President Mathieu Kerekou of Benin (formerly the Kingdom of Dahomey) issued a national apology for the role Africans played in the Atlantic slave trade.[168] Luc Gnacadja, minister of environment and housing for Benin, later said: "The slave trade is a shame, and we do repent for it."[169] Researchers estimate that 3 million slaves were exported out of the Slave Coast bordering the Bight of Benin.[169]

France

On 30 January 2006, Jacques Chirac (the then French President) said that 10 May would henceforth be a national day of remembrance for the victims of slavery in France, marking the day in 2001 when France passed a law recognising slavery as a crime against humanity.[170]

Ghana

President Jerry Rawlings of Ghana apologized for his country's involvement in the slave trade.[168]

Netherlands

At a UN conference on the Atlantic slave trade in 2001, the Dutch Minister for Urban Policy and Integration of Ethnic Minorities Roger van Boxtel said that the Netherlands "recognizes the grave injustices of the past." On 1 July 2013, at the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the Dutch West Indies, the Dutch government expressed "deep regret and remorse" for the involvement of the Netherlands in the Atlantic slave trade. The Dutch government has remained short of a formal apology for its involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, as an apology implies that it considers its own actions of the past as unlawful, and could lead to litigation for monetary compensation by descendants of the enslaved.[171]

Nigeria

In 2009, the Civil Rights Congress of Nigeria has written an open letter to all African chieftains who participated in trade calling for an apology for their role in the Atlantic slave trade: "We cannot continue to blame the white men, as Africans, particularly the traditional rulers, are not blameless. In view of the fact that the Americans and Europe have accepted the cruelty of their roles and have forcefully apologized, it would be logical, reasonable and humbling if African traditional rulers ... [can] accept blame and formally apologize to the descendants of the victims of their collaborative and exploitative slave trade."[172]

Uganda

In 1998, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda called tribal chieftains to apologize for their involvement in the slave trade: "African chiefs were the ones waging war on each other and capturing their own people and selling them. If anyone should apologise it should be the African chiefs. We still have those traitors here even today."[172]

United Kingdom

On 9 December 1999, Liverpool City Council passed a formal motion apologizing for the city's part in the slave trade. It was unanimously agreed that Liverpool acknowledges its responsibility for its involvement in three centuries of the slave trade. The City Council has made an unreserved apology for Liverpool's involvement and the continual effect of slavery on Liverpool's black communities.[173]

On 27 November 2006, British Prime Minister Tony Blair made a partial apology for Britain's role in the African slavery trade. However African rights activists denounced it as "empty rhetoric" that failed to address the issue properly. They feel his apology stopped shy to prevent any legal retort.[174] Blair again apologized on 14 March 2007.[175]

On 24 August 2007, Ken Livingstone (Mayor of London) apologized publicly for London's role in the slave trade. "You can look across there to see the institutions that still have the benefit of the wealth they created from slavery," he said, pointing towards the financial district, before breaking down in tears. He said that London was still tainted by the horrors of slavery. Jesse Jackson praised Mayor Livingstone and added that reparations should be made.[176]

United States

On 24 February 2007, the Virginia General Assembly passed House Joint Resolution Number 728[177] acknowledging "with profound regret the involuntary servitude of Africans and the exploitation of Native Americans, and call for reconciliation among all Virginians". With the passing of that resolution, Virginia became the first of the 50 United States to acknowledge through the state's governing body their state's involvement in slavery. The passing of this resolution came on the heels of the 400th-anniversary celebration of the city of Jamestown, Virginia, which was the first permanent English colony to survive in what would become the United States. Jamestown is also recognized as one of the first slave ports of the American colonies. On 31 May 2007, the Governor of Alabama, Bob Riley, signed a resolution expressing "profound regret" for Alabama's role in slavery and apologizing for slavery's wrongs and lingering effects. Alabama is the fourth state to pass a slavery apology, following votes by the legislatures in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina.[178]

On 30 July 2008, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution apologizing for American slavery and subsequent discriminatory laws. The language included a reference to the "fundamental injustice, cruelty, brutality and inhumanity of slavery and Jim Crow" segregation.[179] On 18 June 2009, the United States Senate issued an apologetic statement decrying the "fundamental injustice, cruelty, brutality, and inhumanity of slavery". The news was welcomed by President Barack Obama.[180]

See also

- Arab slave trade

- Atlantic history

- Atlantic slave trade to Brazil

- Barbary slave trade

- Bristol slave trade

- History of slavery

- Indian indenture system

- Piracy

- Slave Trade Acts

- Slavery in Africa

- Slavery in Britain

- Slavery in Canada

- Slavery in the colonial United States

- Slavery in contemporary Africa

- Slavery in the Ottoman Empire

- Slavery in the Spanish New World colonies

- Slavery in the United States

- United States labor law

- The Slave Route Project

- Edward Colston

References

- "Implications of the slave trade for African societies". London: BBC. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "The capture and sale of slaves". Liverpool: International Slavery Museum. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Sowell, Thomas (2005), "The Real History of Slavery", Black Rednecks and White Liberals, New York: Encounter Books, p. 121, ISBN 978-1594030864

- Mannix, Daniel (1962). Black Cargoes. The Viking Press. pp. Introduction–1–5.

- Weber, Greta (June 5, 2015). "Shipwreck Shines Light on Historic Shift in Slave Trade". National Geographic Society. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- Klein, Herbert S., and Jacob Klein. The Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp. 103–139.

- Ronald Segal, The Black Diaspora: Five Centuries of the Black Experience Outside Africa (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), ISBN 0-374-11396-3, p. 4. "It is now estimated that 11,863,000 slaves were shipped across the Atlantic." (Note in original: Paul E. Lovejoy, "The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on Africa: A Review of the Literature", in Journal of African History 30 (1989), p. 368.)

- Meredith, Martin (2014). The Fortunes of Africa. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 191. ISBN 978-1610396356.

- Patrick Manning, "The Slave Trade: The Formal Demographics of a Global System" in Joseph E. Inikori and Stanley L. Engerman (eds), The Atlantic Slave Trade: Effects on Economies, Societies and Peoples in Africa, the Americas, and Europe (Duke University Press, 1992), pp. 117–44, online at pp. 119–120.

- Stannard, David. American Holocaust. Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Eltis, David and Richardson, David, "The Numbers Game". In: Northrup, David: The Atlantic Slave Trade, 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 2002, p. 95.

- Basil Davidson. The African Slave Trade.

- Thornton 1998, pp. 15–17.

- Christopher 2006, p. 127.

- Thornton 1998, p. 13.

- Chaunu 1969, pp. 54–58.

- Thornton 1998, p. 24.

- Thornton 1998, pp. 24–26.

- Thornton 1998, p. 27.

- "Historical survey, Slave societies". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06.

- Ferro, Mark (1997). Colonization: A Global History. Routledge, p. 221, ISBN 978-0-415-14007-2.

- Obadina, Tunde (2000). "Slave trade: a root of contemporary African Crisis". Africa Economic Analysis. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02.

- Elikia M'bokolo, "The impact of the slave trade on Africa", Le Monde diplomatique, 2 April 1998.

- Thornton, p. 112.

- Thornton, p. 310.

- Slave Trade Debates 1806, Colonial History Series, Dawsons of Pall Mall, London 1968, pp. 203–204.

- Thornton, p. 45.

- Thornton, p. 94.

- Thornton 1998, pp. 28–29.

- Thornton 1998, p. 31.

- Thornton 1998, pp. 29–31.

- Thornton 1998, pp. 37.

- Thornton 1998, p. 38.

- Thornton 1998, p. 39.

- Thornton 1998, p. 40.

- Rodney 1972, pp. 95–113.

- Austen 1987, pp. 81–108.

- Thornton 1998, p. 44.

- Anne C. Bailey, African Voices of the Atlantic Slave Trade: Beyond the Silence and the Shame, Beacon Press, 2005, p. 62.

- Anstey, Roger: The Atlantic Slave Trade and British abolition, 1760–1810. London: Macmillan, 1975, p. 5.