Virginia v. John Brown

Virginia v. John Brown was a criminal trial held in Charles Town, Virginia, in October 1859. The abolitionist John Brown was prosecuted for his involvement in a raid on the United States federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. (Since 1863, both Charles Town and Harpers Ferry are in West Virginia.) On October 16–18, 1859, Brown led 21 armed men, 5 Black and 16 white, to Harpers Ferry, an important railroad junction. His goal was to seize the federal arsenal there and then lead a slave insurrection across the South. Brown and his men engaged in a two-day standoff with local militia and federal troops, in which ten of his men were shot or killed, five were captured, and five escaped.[1] Brown was captured and put on trial in a Virginia state court for treason, murder, and fomenting a slave insurrection. He was found guilty on all counts, and hanged on December 2.

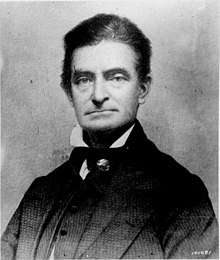

John Brown | |

|---|---|

A daguerreotype of John Brown taken in Kansas, ca. 1856 | |

| Born | May 9, 1800 |

| Died | December 2, 1859 (aged 59) |

| Cause of death | Hanging |

| Resting place | North Elba, New York 44.252240°N 73.971799°W |

| Monuments | Statues in Kansas City, Kansas, and North Elba, New York; John Brown Farm State Historic Site, North Elba, New York; John Brown Museum and John Brown Historic Park, Osawatomie, Kansas; John Brown Tannery Site, Guys Mills, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation | Tanner; cattle, horse, and sheep breeder and trader; farmer |

| Known for | Involvement in Bleeding Kansas; raid on federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia |

| Home town | Hudson, Ohio |

| Movement | Abolitionism |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Children | Watson, Oliver, Owen |

| Parent(s) | Owen |

| Conviction(s) | Guilty of all counts |

| Criminal charge | Treason; murder; fomenting a slave insurrection |

| Trial | Virginia v. John Brown (October 25, 1859-November 2, 1859) |

| Penalty | Death |

| Partner(s) | Secret Six |

| Details | |

| Date | October 16–18, 1859 |

| State(s) | Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia) |

| Location(s) | Harpers Ferry |

| Killed | 7 |

| Injured | 18 |

| Signature | |

Thanks to the recently-invented telegraph, Brown's trial was the first to be reported nationally. Considering its aftermath, it was arguably the most important criminal trial in the history of the country, for it was closely related to the war that quickly followed. More than Brown's raid, his trial determined the fate of the Union.

According to Brian McGinty, the "Brown of history" was thus born in his trial. Had Brown died before his trial, he would have been "condemned as a madman and relegated to a footnote of history". Robert McGlone added that "the trial did magnify and exalt his image. But Brown's own efforts to fashion his ultimate public persona began long before the raid and culminated only in the weeks that followed his dramatic speech at his sentencing."[2] After the sentencing, Brown engaged in extensive correspondence and, glad for the publicity, gave interviews to reporters or anyone else who wanted to talk to him.

Trial

Venue

Brown did not face federal charges. There were no federal court facilities nearby, and transporting the injured Brown and the other defendants to a large city, such as Richmond or Washington DC, and maintaining them there would have been difficult and expensive. And what would this gain? Murder was not a federal crime, and a federal indictment for treason or fomenting slave insurrection would have caused a political crisis (because so many abolitionists would have denounced it). Under Virginia law, fomenting a slave insurrection was clearly and unequivocally a crime. And the defendants could be tried where they were, in Charles Town. "President Buchanan was indifferent to where Brown and his men were tried. ...Virginia Governor Henry Wise, on the other hand, was 'adamant' that the insurgents pay for their crimes through his state's judicial system."[2]:292

The trial, then, took place in the county courthouse in Charles Town, not to be confused with Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital. Charles Town is the county seat of Jefferson County, Virginia, about 7 miles (11 km) west of Harpers Ferry. Since 1863 Jefferson County, including Harpers Ferry and Charles Town, is in West Virginia.

A "large armed force" was stationed at Charles Town "to prevent attempts at rescue."[3]:295 Brown was brought into court "accompanied by a body of armed men. Cannon were stationed in front of the court house, and an armed guard were [sic] patrolling round the jail."[3]:301 "The Governor [kept] the state troops constantly on guard. so that from the time Brown and his men were put in jail until after his execution, Charlestown [sic] had much the appearance of a military camp."[4]:9 Until the day of his execution Brown expected to be rescued by his partisans.[4]:8–9

Interview by Governor Wise

Under Virginia law five days had to pass before the trial. During this time Virginia governor Wise visited and interviewed Brown. At the conclusion he stated:

They are themselves mistaken who take him to be a mad man. He is a bundle of the best nerves I ever saw, cut and thrust and bleeding, and in bonds. He is a man of clear head, courage, fortitude and simple ingenuousness. He is cool, collected and indomitable, and it is but just to hear him say that he was humane to his prisoners and he inspired me with great trust in his integrity as a man of truth. He is fanatic, vain and garrulous, but firm, truthful and intelligent.[4]:8

Grand jury

Brown faced a grand jury on Tuesday, October 25, 1859, just eight days after his capture in the armory. The grand jury was also considering the other prisoners to be tried with Brown: Aaron Stephens, Edwin Coppie, Shields Green, and John Copland. The courtroom was so crowded with spectators that there was not even standing room.[4]:9 At 5 PM the grand jury reported they had not yet finished questioning of witnesses, and the hearing was adjourned until the next day. On October 26 the grand jury returned a true bill of indictment against Brown and the other defendants, charging them with:

- "Conspiring with negroes to produce insurrection",

- Treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

- Murder.[3]:298

Counsel

The next question was what legal counsel Brown was to have. The Court assigned two "Virginians and pro-slavery men", John Faulkner and Lawson Botts, as counsel for him and the other accused. Brown did not accept them; he told the judge that he had sent for counsel, "who have not had time to reach here".[3]:293

I did not ask for any quarter at the time I was taken; I did not ask to have my life spared. The Governor of the State of Virginia tendered me assurances that I should have a fair trial, but under no circumstances whatever will I be able to have a fair trial. If you seek my blood, you can have it at any moment, without this mockery of a trial. I have had no counsel. I have not been able to advise with any one. I know nothing about the feelings of my fellow-prisoners, and am utterly unable to attend in any way to my own defence. My memory don't serve me—my health is insufficient, although improving. There are mitigating circumstances that I would urge in our favor, if a fair trial is to be had; but if we are to be forced, with a mere form, to trial for execution, you might spare yourself that trouble. I am ready for my fate. I beg for no mockery of a trial—no insult; nothing but that which conscience gives or cowardice drives you to practise.

I ask again to be excused from the mockery of a trial. I do not even know what the special design of this examination is; I do not know what is to be the benefit of it to the Commonwealth. I have now little further to ask other than that I may not be foolishly insulted, only as cowardly barbarians insult those who fall into their power.[5]

Brown asked for "a delay of two or three days" for his counsel to arrive.[3]:302 The judge turned down Brown's request: "the expectation of other counsel...did not constitute a sufficient cause for delay, as there was no certainty about their coming. ...The brief period remaining before the close of the term of the Court rendered it necessary to proceed as expeditiously as practicable, and to be cautious about granting delays."[3]:303 The remainder of October 26 was used to choose jurors.

The trial

On Thursday, October 27, the trial proper began. Brown stated that he did not wish to use an insanity defense, as had been proposed to him.[3]:309[4]:12 A court-appointed lawyer said that a Virginia court could only try Brown for acts committed in Virginia, not in Maryland or the federal arsenal. State counsel denied this was relevant.

Brown, having received by telegraph news from a lawyer in Ohio, asked for a delay of one day; this was denied. The state attorney said that Brown's real motive was "to give to his friends the time and opportunity to organize a rescue."[3]:310

On Friday, October 28, "Mr. Hoyt, a young Boston lawyer, arrived as a volunteer counsel for John Brown".[3]:317

Prosecution

The prosecuting attorney was Andrew Hunter.

The central prosecution witness in the trial was Colonel Lewis Washington, of President Washington's family, who had been kidnapped out of his home and held hostage near the Federal Armory. His slaves were militarily "impressed" (conscripted) by Brown, but they took no active part in the insurrection. Other local witnesses testified to the seizure of the Federal Armory, the appearance of Virginia militia groups, and shootings on the railroad bridge. Other evidence described the U.S. Marines' raid on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad engine house occupied by Brown and his men. U.S. Army Colonel Robert E. Lee and cavalry officer J. E. B. Stuart led the Marine raid, and it freed the hostages and ended the standoff. Lee did not appear at the trial to testify, but instead filed an affidavit to the court with his account of the Marines raid.

The manuscript evidence was of particular interest to the judge and jury. Many documents were found on the Maryland farm rented by John Brown under the alias Isaac Smith. These included a Provisional Constitution for a new state, which Brown and his officers had signed. These documents clinched the treason and pre-meditated murder charges against Brown.

The prosecution concluded its examination of witnesses. The defense called witnesses, but they did not appear as subpoenas had not been served on them. Mr. Hoyt said that other counsel for Brown would arrive that evening. Both court-appointed attorneys then resigned, and the trial was adjourned until the next day.[3]:323

Defense

The trial resumed on Saturday, October 29. Two lawyers for Brown appeared, one from Washington and the other from Ohio. They asked for a few hours to read the indictment and the testimony so far given; this was denied.[3]:325–326 The defense called six witnesses.[3]:326–328

George H. Hoyt, another prominent lawyer, arrived a few days later from Massachusetts and took a hesitant role in the closing days of the trial. Hoyt was hired to defend Brown by John W. Le Barnes, one of the abolitionists who had given money to Brown in the past. Samuel Chilton, a lawyer from Washington D.C., was also brought in as Brown's legal counsel. Hiram Griswold, a lawyer from Cleveland, Ohio, arrived late in the trial on October 31 and delivered the defense's closing argument.

The defense claimed that the Harpers Ferry Federal Armory was not on Virginia property, but since the murdered townspeople had died in the streets outside the perimeter of the Federal facility, this carried little weight with the jury. John Brown's lack of official citizenship in Virginia was presented as a defense against treason against the State. Judge Parker dispatched this claim by reference to "rights and responsibilities" and the overlapping citizenship requirements between the Federal union and the various states. John Brown, an American citizen, could be found guilty of treason against Virginia on the basis of his temporary residence there during the days of the insurrection.

Three other substantive defense tactics failed. One claimed that since the insurrection was aimed at the U.S. government it could not be proved treason against Virginia. Since Brown and his men had fired upon Virginia troops and police, this point was mooted. His lawyers also said that since no slaves had joined the insurrection, the charge of leading a slave insurrection should be thrown out. The jury apparently did not favor this claim, either.

Extenuating circumstances were claimed by the defense when they stressed that Colonel Washington and the other hostages were not harmed and were in fact protected by Brown during the siege. This claim was not persuasive as Colonel Washington testified that he had seen men die of gunshot wounds and had been confined for days.

The final plea by the defense team for mercy concerned the circumstances surrounding the death of two of John Brown's men, who were apparently fired upon and killed by the Virginia militia while under a flag of truce. The armed community surrounding the Federal Arsenal did not hold their fire when Brown's men emerged to parley. This incident is noticeable upon a close reading of the published testimony, but is generally neglected in more popular accounts. If the rebels under a flag of truce were deliberately fired upon, it did not appear to be a major issue to the biased judge and jury.

Throughout most of the trial, Brown "appeared to be little interested in what was transpiring." At the close of the trial, Brown elected not to testify on his own behalf.[4]:11

The verdict

The prosecution began its closing argument on Friday, concluding on Monday, October 31.[3]:333 The jury retired to consider its verdict.[3]:334–336

The jury deliberated for only 45 minutes. When it returned, according to the report in the New York Herald, "the only calm and unruffled countenance there" was that of Brown. When the jury reported that it found him guilty of all charges, "not the slightest sound was heard in the vast crowd".[6]

One of Brown's attorneys made "a motion for an arrest of judgment", but it was not argued. "Counsel on both sides being too much exhausted to go on, the motion was ordered to stand over until tomorrow, and Brown was again removed unsentenced to prison" [actually to the Jefferson County jail].[6]

Speech to the court and sentence

On November 2, 1859, at his sentencing, Brown was first asked to stand and say why sentence should not be passed upon him. He arose and made what his first biographer called "[his] last speech":[3]:340

I have, may it please the court, a few words to say.

In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted, the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again, on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case), had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

This court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that "all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them" [Matthew 7:12]. It teaches me, further, to "remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them" [Hebrews 13:3]. I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done as I have always freely admitted I have done in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit; so let it be done!

Let me say one word further.

I feel entirely satisfied with the treatment I have received on my trial. Considering all the circumstances and animosity toward me, it has been fair and more generous than I expected. But I feel no consciousness of guilt. I have stated from the first [day] what was my intention and what was not. I never had any design against the life of any person, nor any disposition to commit treason, or excite slaves to rebel, or make any general insurrection. I never encouraged any man to do so, but always discouraged any idea of that kind.

Let me say, also, a word in regard to the statements made by some of those connected with me. I hear it has been stated by some of them that I have induced them to join me. But the contrary is true. I do not say this to injure them, but as regretting their weakness. There is not one of them but joined me of his own accord, and the greater part of them at their own expense. A number of them I never saw, and never had a word of conversation with, till the day they came to me; and that was for the purpose I have stated.

Now I have done.[3]:340–342

According to Ralph Waldo Emerson, this speech's only equal in American oratory is the Gettysburg Address. It was reproduced in full in 52 American newspapers, making the front page of the Richmond Dispatch and several other papers.[7] Wm. Lloyd Garrison printed it on a broadside and had it for sale in his shop/office (reproduced in Gallery, below).

The judge sentenced him to death by hanging on December 2.[3]:340–342

November, 1859

Under Virginia law a month had to separate the sentence of death and its execution. Governor Wise resisted pressures to move up Brown's execution because, he said, he did not want anyone saying that Brown's rights had not been fully respected.

During the month between his conviction and his execution, Brown wrote many letters, most of which, and a few to him, were collected and published in 1860.[3]:344–372 He also prepared his will.[3]:367–368 He had previously been prevented by the Court from "making a full statement of his motives and intentions through the press", as he desired; the Court had "refused all access to reporters".[3]:295 Now that he had been convicted and sentenced, there were no more restrictions on visitors, and Brown talked to reporters or anyone else that wanted to see him. "He states that he welcomes every one, and that he is preaching, even in jail, with great effect, upon the enormities of slavery."[3]:374

On December 1 he made his will, distributing his few possessions—his surveyor's implements, his silver watch, the family Bible—to his surviving children. Bibles were to be purchased for each of his children and grandchildren.[8]:108

Execution

John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, shortly before noon, in a vacant field several blocks away from the Jefferson County jail, where he was held. John Wilkes Booth and Thomas Jackson (the future Stonewall Jackson) were present, along with 2,000 Federal troops and Virginia militia. (Militia had been stationed in Charles Town continuously from the trial until the execution.[4]:24) On the short trip from the jail to the gallows he was protected on both sides by lines of troops, to prevent an armed rescue. Spectators and reporters were kept far enough away that he could not talk to them, and he made no final statement from the gallows. His last known words are those on a note, passed to a jailor who asked for an autograph:

Charlestown, Va. 2nd December, 1859. I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.

Aftermath

According to the New York Independent,

A fissure has suddenly opened at the very foundation of the peculiar institution of the South, and has disclosed the fact that that institution rests upon a thin crust of lava, which at any moment may yawn asunder and give place to a devouring fire. It is not what John Brown has done or failed to do, but the fearful possibilities that his crazy emeute [sic] has opened to view, which have inspired the South with a terror of coming evil. Foolhardy as was Brown's exploit, regarded merely as a military invasion for the rescue of the oppressed, unjustifiable as it was upon the principles of Christian ethics, yet this singular devotion of an old man to the cause of human freedom, his heroic contempt of his own life, blending with a sacred regard for the lives and property of others, except where these should stand in the way of the deliverance of the oppressed[,] are gradually pervading the public mind with a tone of admiration even for a misguided philanthropy, and startling the South with the idea that a philanthropy which will peril life for its object, is more to be feared than despised.[9]

Gallery

Interior of the engine house at the armory, just before the door is broken down. Note hostages on the left.

Interior of the engine house at the armory, just before the door is broken down. Note hostages on the left. John Brown at his arraignment before a grand jury, drawing dated 1899

John Brown at his arraignment before a grand jury, drawing dated 1899 Trial of John Brown

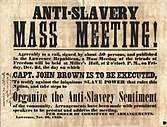

Trial of John Brown Poster calling for anti-slavery meeting in Lawrence, Kansas, the day of Brown's execution.

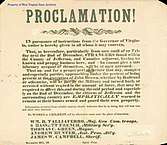

Poster calling for anti-slavery meeting in Lawrence, Kansas, the day of Brown's execution. A warning to citizens of Jefferson County, Virginia, and vicinity to stay home and not attend John Brown's execution.

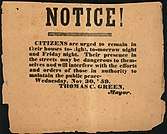

A warning to citizens of Jefferson County, Virginia, and vicinity to stay home and not attend John Brown's execution. Broadside from mayor of Charles Town, Virginia, warning citizens to remain in their houses.

Broadside from mayor of Charles Town, Virginia, warning citizens to remain in their houses. Thomas Hovenden - The Last Moments of John Brown, 1882. Note Brown kissing black baby as he leaves the jail (a legend).

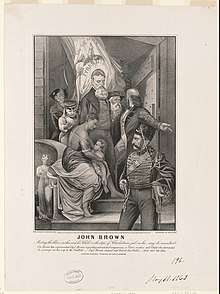

Thomas Hovenden - The Last Moments of John Brown, 1882. Note Brown kissing black baby as he leaves the jail (a legend). John Brown as Christ, en route to his execution, with a black mother and (now) mulatto child. Above his head, the flag of Virginia and its motto, Sic semper tyrannis ("Thus always to tyrants"). Currier and Ives print, from now-lost original by Louis Ransom.

John Brown as Christ, en route to his execution, with a black mother and (now) mulatto child. Above his head, the flag of Virginia and its motto, Sic semper tyrannis ("Thus always to tyrants"). Currier and Ives print, from now-lost original by Louis Ransom. John Brown's last words, passed to a jailor on his way to the gallows. From an albumen print; location of the original is unknown.

John Brown's last words, passed to a jailor on his way to the gallows. From an albumen print; location of the original is unknown._LCCN99614097.jpg) John Brown riding on his coffin to the place of execution.

John Brown riding on his coffin to the place of execution. John Brown on his way to the gallows. Note soldiers on each side of wagon transporting Brown, to prevent an armed rescue.

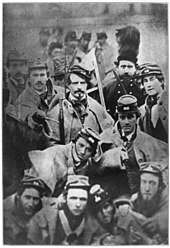

John Brown on his way to the gallows. Note soldiers on each side of wagon transporting Brown, to prevent an armed rescue. Soldiers from Richmond Grays at John Brown's execution. Includes John Wilkes Booth (third row left). For identification of the others pictured, click here.

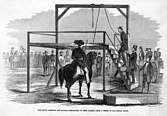

Soldiers from Richmond Grays at John Brown's execution. Includes John Wilkes Booth (third row left). For identification of the others pictured, click here. "John Brown ascending the scaffold preparatory to being hanged", from the December 17, 1859, number of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.

"John Brown ascending the scaffold preparatory to being hanged", from the December 17, 1859, number of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.

See also

References

- WGBH (1998). "The raid on Harpers Ferry". Africans in America. PBS.

- McGlone, Robert E. "Retrying John Brown: Was Virginia Justice "Fair"?". Reviews in American History. 3 (2). pp. 292–298.

- Redpath, James (1860). The public life of Capt. John Brown, with an auto-biography of his childhood and youth. Boston: Thayer and Eldridge.

- Caskie, George E. (1909). Trial of John Brown. Paper read by Hon. George E. Caskie, of Lynchburg before the Virginia State Bar Association, at Homestead Hotel, Hot Springs, Virginia, August 10th, 11th and 12th, 1909. Richmond, Virginia.

- "Trial of Brown". The Liberator. October 28, 1859. p. 3.

- "The Harper's Ferry Tragedy. Conclusion of first day's proceedings". The Liberator. November 4, 1859. p. 3.

- "The Trial at Charlestown". Richmond Dispatch. November 4, 1859. p. 1.

- De Witt, Robert M. (1859). The Life, Trial and Execution of Captain John Brown, Known as "Old Brown of Ossawatomie," with a full account of the attempted insurrection at Harper's Ferry, Virginia. Compiled from official and authentic sources. Inducting Cooke's Confession, and all the Incidents of the Execution. New York: Robert M. De Witt.

- "The Peril of the South". New York Independent. c. November 5, 1859 – via newspapers.com. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

Further reading

- Linder, Douglas O. "John Brown Trial (1859)". Famous Trials.