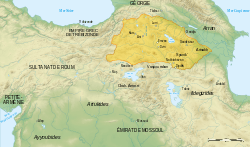

Armenia within the Kingdom of Georgia

| Zakarid Armenia Զաքարյան Հայաստան | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1201–1360 | |||||||||||

Zakarid territories in the early 13th century[2] | |||||||||||

| Status | Fief of Georgia, then of the Mongols | ||||||||||

| Common languages |

Armenian (native language) Georgian | ||||||||||

| Religion |

Armenian Apostolic (predominantly) Georgian Orthodox | ||||||||||

| Government | Principality | ||||||||||

| Atabeg | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Control was taken over Ani | 1201 | ||||||||||

• Conquered by Kara Koyunlu | 1360 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Zakarid Armenia[3] (Armenian: Զաքարյան Հայաստան Zakaryan Hayastan), is a name for a various Armenian princedoms that existed between 1201 and 1360, ruled by the different branches of Mkhargrdzeli dynasty. The Mkhargrdzelis were subject of the Kingdom of Georgia until 1236 when they briefly became direct vassals to the Mongol Empire, and later Georgian monarchs again.[4] Their descendants continued to hold Ani until the 1330s, when they lost it to a succession of Turkish dynasties, including the Kara Koyunlu, who made Ani their capital.

History

Following the collapse of the Bagratuni Dynasty of Armenia in 1045, Armenia was successively occupied by Byzantines and, following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, by the Seljuks.[5] Khosrov, the first historically traceable member of the Mkhargrdzeli family, moved from Armenia to southern Georgia during the Seljuk invasions in the early 11th century. Over the next hundred years, the Zakarids gradually gained prominence at the Georgian court, where they became known as Mkhargrdzeli (Long-shoulder) and became vassals of the Bagrationi kings.

During the 12th century the Bagrations of Georgia enjoyed a resurgence in power, and managed to expand into Muslim occupied Armenia.[6] The former Armenian capital Ani would be captured five times between 1124 and 1209.[7] Under King George III of Georgia, Sargis Zakarid was appointed as governor of Ani in 1161. In 1177, the Zakarids supported the monarchy against the insurgents during the rebellion of Prince Demna and the Orbeli family. The uprising was suppressed, and George III persecuted his opponents and elevated the Mkhargrdzelis.

Despite some complications in the reign of George III, the successes continued in the reign of the Queen Tamar.[6] This was chiefly due to the Armenian generals Zakaria and Ivane.[8][9] The question of liberation of Armenia remained of prime importance in Georgia's foreign policy. Around the year 1199, they retook the city of Ani, and in 1201, Tamar gave Ani to them as a fief.[6] Eventually, their territories came to resemble those of Bagratid Armenia.[5] Zakare and Ivane commanded the Georgian-Armenian armies for almost three decades, achieving major victories at Shamkor in 1195 and Basian in 1203 and leading raids into northern Persia in 1210.

By 1209 Georgia challenged Ayyubid rule in eastern Anatolia and led liberational war for southern Armenia. However during the siege, Georgian general Ivane Mkhargrdzeli accidentally fell into the hands of the al-Awhad on the outskirts of Akhlat, the latter demanded for his release a thirty-year truce. This brought the struggle for the Armenian lands to a stall,[10] leaving the Lake Van region in a relatively secure possession of its new masters – the Ayyubids of Damascus.[11]

Mkhargrdzelis amassed a great fortune, governing all of northern Armenia; Zakare and his descendants ruled in northwestern Armenia with Ani as their capital, while Ivane and his offspring ruled eastern Armenia, including the city of Dvin.

When the Khwarezms invaded the region, Dvin was ruled by the aging Ivane, who had given Ani to his nephew Shanshe, son of Zakare. Georgian army under command of Ivane saw bitter defeat at the battle of Garni, the results of the battle was that a quarter of the Georgian army was annihilated, leaving the country poorly steeled against an upcoming Mongol invasion. Dvin was lost, but Kars and Ani did not surrender.[6]

However, when Mongols took Ani in 1236, they had a friendly attitude towards the Zakarids.[6] They confirmed Shanshe in his fief,[5] and even added to it the fief of Avag, son of Ivane. Avag Mkhargrdzeli, who was raised by Queen Rusudan from the rank of spasalar to amirspasalar (Lord High Constable), and then to that of atabeg (tutor) arranged the submission of Queen Rusudan to the Mongols in 1243, and Georgia officially acknowledged the Great Khan as its overlord.[4] Further, in 1243, they gave Ahlat to the princess Tamta, daughter of Ivane.[6]

During this period of interregnum (1245–1250), with the two Davids absent at the court of the Great Khan in Karakorum, the Mongols divided the Kingdom of Georgia into eight districts (tumen), five of which belonged to the Georgians. The remaining three tumens were Armenian, i.e., the territories of the Zakarids of Ani and Kars; of the Avagids in Syunik and Artsakh; and of the Vagramids (Gagi, Shamkor and the surrounding area).[12]

The Mkhargrdzelis continued their control over Ani until the 1360, when they lost to the Kara Koyunlu Turkoman tribes, who made Ani their capital.[5]

References

- ↑ George A. Bournoutian «A Concise History of the Armenian People», map 19. Mazda Publishers, Inc. Costa Mesa California 2006

- ↑ George A. Bournoutian «A Concise History of the Armenian People», map 19. Mazda Publishers, Inc. Costa Mesa California 2006

- ↑ Chahin, Mack (2001). The Kingdom of Armenia: A History (2. rev. ed.). Richmond: Curzon. p. 235. ISBN 978-0700714520.

- 1 2 Ronald Grigor Suny. The Making of the Georgian Nation. Indiana University Press, p. 40 ISBN 0-253-20915-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Sim, Steven. "The City of Ani: A Very Brief History". VirtualANI. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Minorsky, Vladimir (1953). Studies in Caucasian History. New York: Taylor’s Foreign Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-521-05735-6.

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.aina.org/reports/tykaaog.pdf

- ↑ Suny (1994), p. 39.

- ↑ Lordkipanidze & Hewitt 1987, p. 154.

- ↑ Humphreys 1977, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Babayan, 1969:120.