Gerty Cori

| Gerty Cori | |

|---|---|

Gerty Cori in 1947 | |

| Born |

Gerty Theresa Radnitz August 15, 1896 Prague, Austro-Hungarian Empire |

| Died |

October 26, 1957 (aged 61) Glendale, Missouri, US |

| Cause of death | Myelosclerosis |

| Residence | United States |

| Nationality |

Jewish Austrian-Hungarian |

| Other names | Gerty Theresa Cori |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | Karl-Ferdinands-Universität in Prague |

| Occupation | Biochemist |

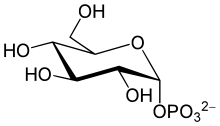

| Known for | Carbohydrate metabolism; The Cori cycle; Identification of Glucose 1-phosphate |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards |

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1947) Garvan–Olin Medal (1948) |

_and_Carl_Ferdinand_Cori.jpg)

Gerty Theresa Cori (née Radnitz; August 15, 1896 – October 26, 1957[2]) was a Jewish Austrian-American biochemist who became the third woman—and first American woman—to win a Nobel Prize in science, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Cori was born in Prague (then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now the Czech Republic). Gerty was not a nickname, but rather she was named after an Austrian warship.[3] Growing up at a time when women were marginalized in science and allowed few educational opportunities, she gained admittance to medical school, where she met her future husband Carl Ferdinand Cori; upon their graduation in 1920, they married. Because of deteriorating conditions in Europe, the couple emigrated to the United States in 1922. Gerty Cori continued her early interest in medical research, collaborating in the laboratory with Carl. She published research findings coauthored with her husband, as well as publishing singly. Unlike her husband, she had difficulty securing research positions, and the ones she obtained provided meager pay. Her husband insisted on continuing their collaboration, though he was discouraged from doing so by the institutions that employed him.

With her husband Carl and Argentine physiologist Bernardo Houssay, Gerty Cori received the Nobel Prize in 1947 for the discovery of the mechanism by which glycogen—a derivative of glucose—is broken down in muscle tissue into lactic acid and then resynthesized in the body and stored as a source of energy (known as the Cori cycle). They also identified the important catalyzing compound, the Cori ester. In 2004, both Gerty and Carl Cori were designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark in recognition of their work in clarifying carbohydrate metabolism.[4]

In 1957, Gerty Cori died after a ten-year struggle with myelosclerosis. She remained active in the research laboratory until the end. She received recognition for her achievements through multiple awards and honors.

Early life and education

Gerty Theresa Radnitz was born into a Jewish family in Prague in 1896. Her father, Otto Radnitz, was a chemist who became manager of sugar refineries after inventing a successful method for refining sugar. Her mother, Martha, a friend of Franz Kafka, was a culturally sophisticated woman.[4] Gerty was tutored at home before enrolling in a lyceum for girls, and at the age of 16 she decided she wanted to be a medical doctor. Pursuing the study of science, Gerty learned that she lacked the prerequisites in Latin, physics, chemistry, and mathematics. Over the course of a year, she managed to study the equivalent of eight years of Latin, five years of science, and five years of math.[3]

Her uncle, a professor of pediatrics, encouraged her to attend medical school, so she studied for and passed the University entrance examination. She was admitted to the medical school of the Karl-Ferdinands-Universität in Prague in 1914, which was unusual for a woman to achieve at that time.

Marriage and early career

While studying she met Carl Cori who was immediately attracted to her charm, vitality, sense of humor and her love of the outdoors and mountain climbing.[5] Gerty and Carl had both entered medical school at eighteen and both graduated in 1920. They married that same year.[3] Gerty converted to Catholicism, enabling her and Carl to marry in the Roman Catholic Church.[6][7] They moved to Vienna, Austria, where Gerty spent the next two years at the Carolinen Children's Hospital, and her husband worked in a laboratory.[5] While at the hospital, Gerty Cori worked on the pediatrics unit and conducted experiments in temperature regulation, comparing temperatures before and after thyroid treatment, and published papers on blood disorders.[4]

Carl was drafted into the Austrian army and served during World War I.[3] Life was difficult after the war, and Gerty suffered from xerophthalmia caused by severe malnutrition due to food shortages. These problems, in conjunction with the increasing anti-Semitism, contributed to the Coris' decision to leave Europe.[8]

Working in the United States

In 1922, the Coris both immigrated to the United States (Gerty six months after Carl because of difficulty in obtaining a position) to pursue medical research at the State Institute for the Study of Malignant Diseases (now the Roswell Park Cancer Institute) in Buffalo, New York. In 1928, they became naturalized citizens.[9][10] The director for the Institute threatened to dismiss Gerty if she did not cease collaborative research with her husband. She continued to work with Carl and was also kept on at the Institute.[3]

Joseph Larner[5]

Although the Coris were discouraged from working together at Roswell, they continued to do so, specializing in investigating carbohydrate metabolism. They were particularly interested in how glucose is metabolized in the human body and the hormones that regulate this process.[5] They published fifty papers while at Roswell, with first author status going to the one who had done most of the research for a given paper. Gerty Cori published eleven articles as the sole author. In 1929, they proposed the theoretical cycle that later won them the Nobel Prize, the Cori cycle.[9] The cycle describes how the human body uses chemical reactions to break some carbohydrates such as glycogen in muscle tissue into lactic acid, while synthesizing others.[8]

Washington University

The Coris left Roswell in 1931 after publishing their work on carbohydrate metabolism. A number of universities offered Carl a position but refused to hire Gerty. Gerty was informed during one university interview that it was considered "unamerican" for a married couple to work together.[4] Carl refused a position at the University of Buffalo because the school would not allow him to work with his wife.[3]

In 1931, they moved to St. Louis, Missouri, as Washington University offered both Carl and Gerty positions, although Gerty's rank and salary were much lower than her husband's.[3] Despite her research background, Gerty was only offered a position as a research associate at a salary one tenth of that received by her husband;[11] she was warned that she might harm her husband's career.[9] Washington University's Chancellor, Arthur Compton, made a special allowance for Gerty to hold a position there, going against the university's nepotism rules. Gerty had to wait thirteen years before she attained the same rank as her husband.[3] In 1943, she was made an associate professor of Research Biological Chemistry and Pharmacology. Months before she won the Nobel Prize, she was promoted to full professor, a post she held until her death in 1957.[12]

They continued their collaboration at Washington University. While working with minced frog muscle, they discovered an intermediate compound that enabled the breakdown of glycogen, called glucose 1-phosphate, now known as the Cori ester.[8] They established the compound's structure, identified the enzyme phosphorylase that catalyzed its chemical formation, and showed that the Cori ester is the beginning step in the conversion of the carbohydrate glycogen into glucose (large amounts of which are found in the liver).[4] It can also be the last step in the conversion of blood glucose to glycogen, as it is a reversible step.[13] Gerty Cori also studied glycogen storage disease, identifying at least four forms, each related to a particular enzymatic defect.[14] She was the first to show that a defect in an enzyme can be the cause of a human genetic disease.[15]

Gerty and Carl Cori collaborated on most of their work, including that which won them the 1947 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discovery of the course of the catalytic conversion of glycogen". They received one half the prize, the other half going to the Argentinian physiologist, Bernardo Houssay "for his discovery of the part played by the hormone of the anterior pituitary lobe in the metabolism of sugar".[16] Their work continued to clarify the mechanisms of carbohydrate metabolism, advancing understanding of the reversible conversion of sugars and starch, findings which proved crucial in the development of treatments for diabetics.[4]

Awards and recognitions

In 1947 Gerty Cori became the third woman—and the first American woman—to win a Nobel Prize in science, the previous recipients being Marie Curie and Irène Joliot-Curie. She was the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[18] She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1953.[19] Cori was the fourth women elected to the National Academy of Sciences.[20] She was appointed by President Harry S. Truman as board member of the National Science Foundation, a position she held until her death.[12]

Gerty was also a member of the American Society of Biological Chemists, the American Chemical Society and the American Philosophical Society. She and her husband were presented jointly with the Midwest Award (American Chemical Society) in 1946 and the Squibb Award in Endocrinology in 1947. In addition, Cori received the Garvan-Olin Medal (1948), the St. Louis Award (1948), the Sugar Research Prize (1950), the Borden Award (1951).[21] She received honorary Doctor of Science degrees from Boston University (1948), Smith College (1949), Yale University (1951), Columbia University (1954), and the University of Rochester (1955).

The twenty-five square foot laboratory shared by Cori and her husband at Washington University was deemed a National Historic Landmark by the American Chemical Society in 2004.[4] Six of the scientists mentored by Cori and her husband went on to win Nobel Prizes, which is only superseded by the mentored scientists of British physicist J.J. Thomson [22][23]

In 1949 she was awarded the Iota Sigma Pi National Honorary Member for her significant contribution.[24] The crater Cori on the Moon is named after her,[25] as is the Cori crater on Venus.[26] She shares a star with her husband on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[27]

Cori was honored by the release of a US Postal Service stamp in April, 2008.[28] The 41-cent stamp was reported by the Associated Press to have a printing error in the chemical formula for glucose-1-phosphate (Cori ester). The stamp is being distributed despite the error.[29] Her description reads: "Biochemist Gerty Cori (1896–1957), in collaboration with her husband, Carl, made important discoveries—including a new derivative of glucose—that elucidated the steps of carbohydrate metabolism and contributed to the understanding and treatment of diabetes and other metabolic diseases. In 1947, the couple was awarded a half share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine."[30]

The US Department of Energy named the NERSC-8 supercomputer installed in 2015/2016 after Cori.[31]

Although prejudiced against in her time for being a woman, today she is the more celebrated of the Coris as she considered a pioneer as a woman of science.[3]

Final years

Just before winning the Nobel prize, while they were on a mountain climbing trip, the Coris learned that Gerty Cori was ill with myelosclerosis, a fatal disease of the bone marrow.[4] During her years at the Institute for the Study of Malignant Disease, Gerty had studied the effects of X-rays on the human body, which was thought to contribute to her illness.[3] She struggled for ten years with the illness while continuing her scientific work; only in the final months did she let up. In 1957, she died in her home.[4] Gerty was cremated and her ashes scattered. Later, her son erected a cenotaph for Gerty and Carl Cori in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

She was survived by her husband and their only child, Tom Cori, who married the daughter of conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly.[8][32][33]

Carl Cori remarried in 1960 to Anne Fitzgerald-Jones. The two later moved to Boston, where Carl taught at Harvard Medical School. He continued to work there until his death at the age of eighty-eight.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ "Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori (1896–1957) and Carl Ferdinand Cori (1896–1984) 1947". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1947". Elsevier Publishing Company. 1964. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Shepley, Carol Ferring (2008). Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine Cemetery. St. Louis, MO: Missouri History Museum.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Carl and Gerti Cori and Carbohydrate Metabolism". American Chemical Society. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Larner, Joseph (1992). "Gerty Theresa Cori". National Academy of Sciences. pp. 113, 124, 125. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-11-10. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

- ↑ https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/cori.html

- 1 2 3 4 Chemical Heritage Foundation. "Flying, Hopping and Rolling". hemheritage.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 National Library of Medicine. "Dr. Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori". nih.gov. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ "Nobel Lectures – Physiology or Medicine 1942–1962". Elsevier Publishing Company. 1964. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri. "Gerty Theresa Cori (1896–1957)". Bernard Becker Medical Library. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- 1 2 Washington University School of Medicine. "Gerty Theresa Cori (1896–1957)". Bernard Becker Medical Library. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ "Carl Ferdinand & Gerty Theresa Cori". nobel-winners.com. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ Rothenberg, Marc (2000). The history of science in the United States : an encyclopedia ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). New York: Garland. ISBN 0815307624.

- ↑ Smeltzer, Ronald K. (2013). Extraordinary Women in Science & Medicine: Four Centuries of Achievement. The Grolier Club.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1947". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ Washington University School of Medicine. "Gerty Theresa Cori". Bernard Becker Medical Library. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ "Facts on the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter C" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ↑ Gardner, A. L. (1997). "Gerty Cori, Biochemist, 1896–1957" (PDF). Women Life Scientists: Past, Present, and Future – Connecting Role Models to the Classroom Curriculum. American Physiological Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ "Francis P. Garvan-John M. Olin Medal". American Chemistry Society. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ http://www.probashionline.com/jj-thomson-nobel-prize-factory/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._J._Thomson. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "PROFESSIONAL AWARDS". Iota Stigma Pi: National Honor Society for Women in Chemistry. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature". usgs.gov. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ "Cori House - Cori Crater - Extraterrestrial Locations on Waymarking.com". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ Keim, Brandon (January 10, 2008). "U.S. Postal Service Gets Scientific With New Stamps". wired.com. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ Associated Press (January 15, 2008). "Stamp Honoring Biochemist Bears Error". Fox News. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ United States Postal Service (March 6, 2008). "Four Legends of American Science Now on U.S. Postage Stamps". usps.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ "NERSC-8 supercomputer".

- ↑ "Nobels All Around". Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- ↑ "Anne Cori". Retrieved 2012-09-23.

Further reading

- Exton, John H. (2013). Crucible of science : the story of the Cori Laboratory. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199861071.

- Ignotofsky, Rachel (2016). Women in science: 50 fearless pioneers who changed the world (1 ed.). New York: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 9781607749769.

| Library resources about Gerty Cori |

| By Gerty Cori |

|---|

- Leroy, Francis (2003). A century of Nobel Prizes recipients: chemistry, physics, and medicine. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8247-0876-8.

- McGrayne, Sharon Bertsch (2001). Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles and Momentous Discoveries. National Academy Press. ISBN 0-309-07270-0.

- Opfell, Olga S (1978). The Lady Laureates: Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize. Metuchen, N.J. & London: Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 183–193. ISBN 0810811618.

- Reynolds, Moira Davison (2004). American women scientists: 23 inspiring biographies, 1900–2000. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 0786421614.

External links

- Carl and Gerti Cori and Carbohydrate Metabolism from American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks

- “Glories of the Human Mind” by Gerty Cori

- Bernardo A. Houssay Memorial to Gerty Theresa Cori

- Gerty Cori Memorabilia

- Nobel lecture by Carl Cori and Gerty Cori

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir