U.S. Route 80 in Arizona

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Broadway of America | ||||

|

1951 alignment of US 80 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by ADOT | ||||

| Length | 497.67 mi[1][2] (800.92 km) | |||

| Existed | November 11, 1926–October 6, 1989 | |||

| History |

Formed as Dixie Overland Highway in 1917 Part of Old Spanish Trail and Bankhead Highway Truncated to Benson in 1977 Replaced by Designated historic in 2018 | |||

| Tourist routes |

| |||

| Major intersections (In 1951) | ||||

| West end |

| |||

| East end |

| |||

| Location | ||||

| Counties | Yuma, Maricopa, Pinal, Pima, Cochise[1] | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

U.S. Route 80 (US 80) also known as the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, the Broadway of America and the Jefferson Davis Highway was a major transcontinental highway which existed in the U.S. state of Arizona from November 11, 1926, to October 6, 1989. At its peak, US 80 traveled from the California border in Yuma to the New Mexico state line near Lordsburg. US 80 was an important highway in the development of Arizona's car culture. Like its northern counterpart, US 66, the popularity of travel along US 80 helped lead to the establishment of many unique road side businesses and attractions, including many iconic motor hotels and restaurants.

US 80 was a particularly long highway, reaching a length of almost 500 miles (800 km) within the state of Arizona alone. With the advent of the Interstate Highway System, Interstate 10 and Interstate 8 both replaced US 80 within the state. US 80 was removed from Arizona in 1989; the remainder of it now being State Route 80. In September 2018, the Arizona Department of Transportation designated former segments of the highway as Historic U.S. Route 80.

Route description

On its journey across Arizona, US 80 made two indirect loops to both Phoenix and Douglas. Both loops were likely bypassed often by travelers, using SR 84 and SR 86 respectively to decrease travel time between California and New Mexico.[3] The odd shape created by the two "loops" gave US 80 an incredible length through the state of Arizona alone, coming close to 500 miles (800 km) in total. In 1934, US 80 was 500.5 miles (805.5 km) long.[4] By 1951, the total length had reduced to about 498 miles (801 km), shrinking further to 488 miles (785 km) in 1956 with the bypass of Arlington.[1][5]

US 80 entered Arizona from New Mexico on current New Mexico State Road 80 and Arizona State Route 80 near Rodeo. US 80 wound southwest into Douglas intersecting with US 666 (now US 191). From Douglas, US 80 ran northwest, then north through Lowell, Bisbee, Tombstone and St. David meeting up with SR 86 in Benson.[1][5][6] The route between New Mexico and Benson has been subject to change. Prior to the construction of the Mule Pass Tunnel in 1952, US 80 used Main Street and North Old Divide Road through Bisbee. Through Tombstone, US 80 once used Allen Street (which is now a pedestrian mall). Many older gradual curves and alignments of US 80 are visible between Douglas and Benson, some of which are still driveable. Originally, US 80 entered Benson on what is now Catarina Street and Gila Street, before later being switched to the route currently followed by SR 80. US 80 met with SR 86 (now I-10 Business) at a grade separated interchange in downtown Benson, where the latter highway ended (until picking up again at US 89 in Tucson). Much of US 80 to Tucson has since been overlaid by Interstate 10 with a few exceptions. Near Exit 302, an old gradual curve of US 80 constitutes as Titan Drive. Older US 80 followed Marsh Station Road between I-10 exits 289 and 281 until the early 1950s. US 80 followed the north Frontage road past Exit 281 before merging back into the routing of I-10.[6]

In Tucson, US 80 left I-10's routing and headed west along Benson Highway, briefly merging back into I-10's routing to meet US 89 and SR 84 at 6th Avenue.[7][8] US 80, US 89 and SR 84 headed north through Tucson on 6th Avenue, Stone Avenue, Drachman Street and Oracle Boulevard (now Oracle Road). SR 84 split off heading west to Casa Grande at Casa Grande Highway (now West Miracle Mile).[8] US 80 and US 89 continued north along present day SR 77 and SR 79 through Florence. The older route in Florence took the SR 79 business route, Main Street and Ruggles Street through town. US 80/US 89 met up with US 60/70 at Florence Junction, where all four highways headed west towards Phoenix. Modern US 60 still travels this route. The original Florence Junction lies north of the current one. From this point, the earliest routings of US 60, US 80 and US 89 used El Camino Viejo, an old gravel road, before re-joining modern US 60 west of Florence. The latter alignment used modern US 60. At Apache Junction, Old US 60/US 70/US 80/US 89 continued heading northwest onto Old West Highway where present day US 60 turns west onto the Superstition Freeway, then turned west onto East Apache Trail at the intersection with SR 88.[6]

The four highways continued heading west on Apache Trail/Main Street through Mesa into Tempe, where the concurrent routes turned north onto Mill Street, crossed the Salt River then curved west onto Van Buren Street into Phoenix. At the intersection with Grand Avenue, US 60, US 70 and US 89 left US 80 heading northwest to Wickenburg.[5] US 80 continued west on Van Buren, then turned south onto 17th Avenue, passing in front of the Arizona State Capitol then turned west onto Buckeye Road. US 80 headed west through Avondale, Goodyear and Buckeye using Buckeye Road, MC 85 and Baseline Road. US 80 turned south at the junction with SR 85.[6]

The final route of US 80 took SR 85 south to Gila Bend, while the older route, which was bypassed in 1951, took an "S" shape further west following the Gila River, crossing it at one point over a 1927 bridge south of the Gillespie Dam.[1][5] The older route is known today as "Old US 80 Highway" and is only accessible from SR 85 via Hazen Road and Wilson Road. US 80 met SR 84 again in Gila Bend, where it curved west through town on the Interstate 8 Business Loop, then followed what is now the I-8 south Frontage Road before being subsumed into I-8. The old route of US 80 breaks away from time to time and appears within the freeway median. Around Exit 78, US 80 curved briefly onto the North Frontage Road, passed in front of a Texaco station (now abandoned) then took the south Frontage Road through Dateland. West of Dateland, US 80 became the present day eastbound lanes of Interstate 8 before breaking off again at Exit 54 under the guise of Old Highway 80 through Mohawk Pass along with the hamlets of Owl and Tacna before passing through the town of Wellton. Between Mohawk Pass and Telegraph Pass, there are a few older incarnations of US 80 which deviate from the main route. Some of these older routings are no longer maintained.[6]

West of Wellton, post 1928 US 80 followed present day I-8 through the Telegraph Pass (part of which can be seen around the point where the eastbound and westbound lanes of I-8 switch over) to the I-8 Business Loop, while the earlier route followed Avenue 20 E from Ligurta to a Gravel Road following the Union Pacific Railroad through the ghost town of Dome then southwest along present day US 95 and an abandoned road parallel to the railroad where it met up with the later route in Yuma. US 80 travelled through town along the I-8 Business Loop, turning north, crossing an intersection with US 95 to the Colorado River. The older route used the 1914 Ocean-to-Ocean Bridge, which was bypassed in 1956 to cross the Colorado River, while the later alignment continued straight ahead into California. Upon crossing the Colorado River to the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation, the older route was still in Arizona. Unlike most of the California and Arizona state border which resides along the Colorado River, the border temporarily cuts north here through the Reservation then east back to the Colorado. This places several acres of land on the western side of the river in Arizona. For a few hundred feet, the state border runs along the western shoulder of pre-1956 US 80. A short distance north of the bridge, the highway curved left, crossing into California and arriving at a now abandoned Agricultural Inspection Station before continuing west towards San Diego.[6]

History

Background

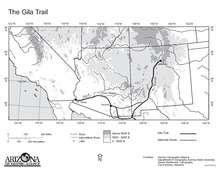

The general path of the Gila Trail in Arizona was traversed by Native Americans for thousands of years. The first non-Native person to travel the Gila Trail was a Spanish owned African slave named Esteban, who had been brought to North America in 1527 as part of the colonization of Florida by Charles V of Spain. In 1538, Esteban accompanied a Franciscan Monk by the name of Marcos de Niza on a quest, which included travelling along the Gila Trail.[9][10] Father Eusebio Kino utilized the Gila Trail to establish missions across present day southern Arizona and California.[11] In 1821, southern Arizona had become part of Mexico.[12] The first Americans on the trail were 19th Century fur trappers, who made use of the nearby Gila River's beaver population. During the Mexican-American War Lieutenant General Stephen W. Kearney of the United States Army sent his Army of the West over the Gila Trail.[13] Following the Mexican-American War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the land surrounding the Gila Trail became part of the United States and was organized as New Mexico Territory in 1850.[14][15] After 1848, Gila Trail had become a popular and heavily traveled wagon route to California. By this time it was now known as Cooke's Wagon Road. The new name was in reference to Captain Philip St. George Cooke, leader of the Mormon Battalion, whom had used the road shortly after General Kearny.[16] In 1863, the western part of New Mexico Territory was re-established as Arizona Territory.[12][14]

By 1909, Cooke's Wagon Road had become the East-West Territorial Road and North-South Territorial Road respectively. The former route travelled between Yuma and Phoenix while the latter travelled between Phoenix, Tucson and Douglas.[17] In February 1912, Arizona was accepted into the union as a state.[12][14] Using funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Ocean-to-Ocean bridge was constructed between Winterhaven, California, and Yuma in 1914.[18] Between 1917 and 1919, the Dixie Overland Highway was established from Savannah, Georgia, to San Diego, California, becoming the first Auto trail to be designated over what would later be U.S. Route 80.[19] From Yuma to New Mexico, the Dixie Overland Highway followed the basic route of US 80 in Arizona very closely.[6] This was joined by the Bankhead Highway in 1920 and the Old Spanish Trail in 1923.[20][19][6] In 1919 and 1920, the auto routes between Dome and Buckeye suffered extensive damage from flooding. This was due to the three routes being located on the Gila River floodplain. The Arizona Highway Department decided to construct a new southern route following the Southern Pacific Railroad more closely through Gila Bend. The new route was completed in 1922.[21] Up through 1924, the Bankhead Highway, Dixie Overland Highway and Old Spanish Trail still followed the older route.[22] By the next year, the trio had been realigned to the newer alignment and paving of the routes was also taking place.[23] In the eastern part of the state, the Arizona Highway Department with the assistance of federal financial aid as well as financial aid from both Pima and Cochise counties, constructed the concrete arch Ciénega Bridge east of Tucson between 1920 and 1921.[24]

National Highway Status

In April 1925, the Joint Board on Interstate Highways, appointed by the then Secretary of Agriculture to simplify the transcontinental highways, proposed a new nationwide numbered highway system. The new highways were to follow a uniform standard of shields and numbering. This system was to become the U.S. Numbered Highway System. By October 1925, a proposed route under the numeric designation "80" was proposed along a similar path to the Dixie Overland Highway, Old Spanish Trail and Bankhead Highway. On November 11, 1926, the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) approved of the new system, which included US 80 between Savannah, Georgia and San Diego, California.[19][25]

In 1927, a steel truss bridge was constructed over the Gila River next to the Gillespie Dam. Prior to the construction of the bridge, traffic utilized a concrete apron constructed at the foot of the dam to cross the river. At the time, it was the largest steel structure in the state of Arizona. The bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 5, 1981.[26] In 1928, the section of US 80 through telegraph pass was constructed, being paved by 1930.[27][28] US 80 also became part of the Broadway of America route in 1930, between Yuma and Phoenix as well as between Tucson and the New Mexico border. The rest of the Broadway of America in Arizona consisted of SR 87 and SR 84 between Tucson and Phoenix via Casa Grande.[6] In 1931, the Mill Street Bridge in Tempe was constructed.[29] Reconstruction and paving on the section through Mule Pass occurred in 1932. The Stone Avenue railroad underpass in Tucson was completed in 1936.[24] By 1935, the entire highway was paved within the state of Arizona, save for a small section between Florence and Oracle Junction.[30] By 1946, that section was reconstructed and paved.[31] Further reconstruction of the section through Telegraph Pass was completed in 1948. The Mule Pass Tunnel was constructed in 1952, becoming the longest tunnel in Arizona. Two straighter and faster alignments of US 80 were constructed in 1956, bypassing the Gillespie Dam area and Cienega Creek.[5] In 1961, the Arizona Highway Commission voted to designate the entirety of US 80 in Arizona as part of the Jefferson Davis Highway.[32]

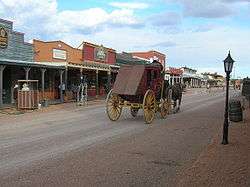

After the end of the Second World War, the highway's popularity increased dramatically. In the 1950s, more motorists traveled on US 80 between Arizona and California than on the famous US 66.[3] Like its northern counterpart, US 80 also featured many iconic road side businesses and attractions, which included Boothill Cemetery and the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Stoval's Space Age Lodge in Gila Bend, Yuma Territorial Prison, the Geronimo Surrender Monument near Douglas and the Painted Rock Petroglyph Site. Rows of iconic neon signed motels aligned US 80 in the many towns and cities it passed through, including Tucson's famous Miracle Mile. As of 2016, many of these attractions and structures have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[33]

Following the creation of the Interstate Highway System in 1957,[34] Interstate 10 and Interstate 8 were both slated to replace US 80.[35] In 1948, the Arizona Highway Department approved construction of the Tucson Controlled Access Highway, a freeway bypass around the core of Tucson. This would become one of the first sections of I-10. Though a state highway, initial construction of the bypass was funded by a 1948 city bond issue passed by the city of Tucson.[36][37] The new bypass originally ran between Congress Street and Miracle Mile. At first, this bypass lacked overpasses and interchanges between Grant Road and Speedway Boulevard.[37] The new bypass was extended eastward by 1956 to an interchange with US 80 and US 89 at 6th Avenue and Benson Highway.[5] By November, the bypass was signed SR 84A.[38] Construction started in 1958 to rebuild SR 84A to Interstate standards.[37] In 1957, work began on a section of Benson Highway (US 80) southeast of Tucson to upgrade the road into a four lane divided highway. Of the 7.25 miles (11.67 kilometres) of upgraded road, 4.25 mi (6.84 km) were slated to become part of I-10 and be built to full interstate standards. The segment became the first federally funded Interstate Highway construction project in Arizona.[39] This section was completed by December 1960.[40] The new section of I-10 had full freeway interchanges and frontage roads at Craycroft Road and Wilmot Road with a third planned later for Valencia Road.[40][39] Other sections of US 80 and SR 86 east of Tucson were also being upgraded into new sections of I-10, with a total of four freeway interchanges between Tucson and Benson complete.[40] Other sections were rebuilt into a four lane divided highway around 1958.[41] I-10 west of 6th Avenue and Benson Highway up to Flowing Wells was completed by 1961, with a sections north of Tucson through Marana well under construction.[37]

By 1963 construction was under way on rebuilding sections of US 80 and SR 84 between Casa Grande and Yuma into I-8 as well as parts of SR 84 between Picacho and Casa Grande into I-10.[42] Most of I-8 through Arizona was completed by 1971 as well as most of I-10 in the southeastern part of the state. Most of US 80 had been fully rebuilt into I-8 between Blaisdell and Gila Bend, save for a standalone section between Ligurta and Mohawk. In the eastern part of Arizona, I-10 had been completed between 6th Avenue and Valencia Road as well as taking over all of US 80 between Valencia Road and 4th Street in Benson. Both Interstates were complete between Gila Bend and Tucson, replacing or bypassing almost all of SR 84. Between Benson and the New Mexico state line near San Simon, former SR 86 had been rebuilt into I-10 and decommissioned.[43]

With new Interstate Highways taking its place as the main routes, US 80 was becoming obsolete. Between 1964 and 1969, California retired its section of US 80 in favor of I-8, effectively moving the western end of US 80 to the California state line in Yuma.[19] In 1977, Arizona requested a truncation of US 80 to Benson. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) approved the request, decommissioning all of US 80 between Yuma and Benson as of October 28 of that year.[19] Part of the section of US 80 between Gila Bend and Phoenix became an extension of SR 85.[44] In 1989, both Arizona and New Mexico requested the elimination of US 80 in both states. The request was approved by AASHTO on October 6.[19] The remaining section of US 80 in Arizona was subsequently downgraded to SR 80.[45] A former section of US 80 between Buckeye and Phoenix, signed as SR 85 at the time, was still used by Interstate traffic through Phoenix until I-10 completed construction through Phoenix in 1990.[46][44] A few sections of old US 80 throughout Arizona pay homage to the retired highway in their names, such as Old U.S. Highway 80 between Gila Bend and Buckeye.[6]

Historic Route 80

.svg.png)

In 2012, the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation (also known as the THPF) embarked on preliminary work needed to apply for a state historic designation of US 80 in Arizona. The foundation commenced survey and mapping work on old sections of the route the same year.[47] Over $100,000 was spent by the THPF to initiate the historic designation process.[3] Further research by the THPF utilized essays written for the Arizona Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Administration as well as a US 80 driving guide written by Jeff Jensen. Further resources were obtained through the special collections of the University of Arizona and Arizona Historical Society. Findings by the THPF concluded at least 40 separate segments of former US 80 in Arizona survive un-interrupted.[3] In July 2016, the THPF finished all necessary preparation work for a historic designation and submitted a formal application for the Historic US 80 designation to the ADOT Parkways, Historic and Scenic Roads Advisory Committee.[47] The proposal included several attached letters of support from various historical committees, mayors and city council members of several towns which the designation would affect.[33] During a meeting on June 20, 2017, the Parkways, Historic and Scenic Roads Advisory Committee decided to unanimously recommend the Historic Route 80 designation to the Arizona State Transportation Board.[47] By August 2018, ADOT was close to completing required reports for the Arizona State Transportation Board needed to sign and designate the segments of Historic US 80 that are part of the state highway system. ADOT is also working with respective local governing bodies to sign and designate the segments that are no longer part of the state highway system.[3] On September 21, 2018, all preparation work was complete and the ADOT Parkways, Historic and Scenic Roads Advisory Committee officially adopted US 80 as a state designated Historic Road.[48] The Historic Route designation connects to and supplements Historic Route 80 in California.[47] Historic US 80 is the fourth state designated Historic Route in Arizona, joining Historic Route 66, the Jerome-Clarkdale-Cottonwood Historic Road (Historic US 89A) and the Apache Trail Historic Road.[49]

In parallel with the Historic Route 80 designation project, the City of Tucson submitted an application to add a segment of former US 80, known as Miracle Mile, to the National Register of Historic Places in Summer 2016.[47] On December 11, 2017 the application was approved and the segment added to the NRHP became known as the Miracle Mile Historic District. The Historic District includes part of Stone Avenue, Drachman Street, the southern segment of Oracle Road, West Miracle Mile (former SR 84) and a small two block section of Main Avenue south of the intersection of Oracle and Drachman. The Miracle Mile Historic District also includes over 281 man made structures including historic motor hotels among other roadside attractions and local businesses.[50]

Major intersections

This list follows the 1951 alignment.

| County | Location | mi[1][2] | km | Destinations[8][51][6][52] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuma | Yuma | 0.00 | 0.00 | California state line | |

| Colorado River | 0.04 | 0.064 | Ocean To Ocean Bridge | ||

| Yuma | 2.63 | 4.23 | |||

| Maricopa | Gila Bend | 119.15 | 191.75 | Northern terminus of SR 85. | |

| 120.06 | 193.22 | Western terminus of SR 84; SR 84 bypassed the US 80 Phoenix "Loop" | |||

| Gila River | 142.37 | 229.12 | Gillespie Dam Bridge | ||

| Phoenix | 194.64 | 313.24 | Western/northern terminus of concurrency with US 60, US 70 and US 89 | ||

| Tempe | 202.77 | 326.33 | Washington Street west – Phoenix | Now Center Parkway | |

| Salt River | 203.32 | 327.21 | Mill Avenue Bridge | ||

| Mesa | 210.46 | 338.70 | |||

| Pinal | Apache Junction | 227.14 | 365.55 | Western terminus of SR 88. | |

| Florence Junction | 243.54 | 391.94 | Eastern terminus of concurrency with US 60 and US 70 | ||

| Florence | 257.88 | 415.02 | Hunt Highway west | ||

| 258.00 | 415.21 | Bridge over the Gila River | |||

| 260.91 | 419.89 | Eastern terminus of SR 287. | |||

| Oracle Junction | 302.90 | 487.47 | Southern terminus of SR 77. | ||

| Pima | Tucson | 321.98 | 518.18 | Bridge over the Rillito River | |

| 324.30 | 521.91 | Northern traffic circle on Oracle Boulevard; Western terminus of concurrency with SR 84; Former eastern terminus of SR 84. | |||

| 329.74 | 530.67 | Southern terminus of concurrency with US 89; Eastern terminus of concurrency with SR 84; Eastern terminus of SR 84[7] | |||

| Vail | 350.69 | 564.38 | Northern terminus of SR 83. | ||

| Cienega Creek | 353.51 | 568.92 | Ciénega Bridge | ||

| Cochise | Benson | 375.83 | 604.84 | Western terminus of SR 86 eastern segment; SR 86 along with SR 14 in New Mexico bypassed the US 80 "Loop" to Douglas | |

| Tombstone | 396.51 | 638.12 | Eastern terminus of SR 82. | ||

| | 415.19 | 668.18 | Eastern terminus of SR 90. | ||

| Lowell | 426.01 | 685.60 | Eastern terminus of SR 92. | ||

| Douglas | 446.92 | 719.25 | Western terminus of US 666 concurrency. | ||

| 447.84 | 720.73 | Eastern terminus of US 666 concurrency. | |||

| | 497.67 | 800.92 | New Mexico state line | ||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

Structures and attractions

The following is an incomplete list of notable attractions and structures along old US 80 in Arizona:[33]

- Ocean To Ocean Bridge, Yuma

- Ruins of Dome, Arizona

- The Space Age Lodge, Gila Bend, built in 1962 and currently owned and run by Best Western[53]

- Gillespie Dam, Gila Bend

- Gillespie Dam Bridge, Gila Bend, 1927 bridge across the Gila River next to the Gillespie Dam[26]

- Agua Caliente, Arizona

- Horseshoe Cafe, Benson, 1940s cafe[54]

- Arizona State Capitol, Phoenix

- Tucson Inn, Tucson, part of the Miracle Mile Historic District[50]

- Ciénega Bridge, Historic concrete arch bridge in Pima County[24]

- O.K. Corral and C.S. Fly's Photo Gallery, Tombstone, site of the infamous gunfight between the Wyatt Earp, Virgil Earp, Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday against the Clantons[55]

- Queen Mine, Bisbee, a copper mine opened in the late 19th century and ceased mining operations in 1975 that is open for public tours[56]

- Gadsden Hotel, Douglas

- Geronimo Surrender Monument, Douglas

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shell Oil Company; H.M. Gousha Company (1951). Shell Highway Map of Arizona and New Mexico (Map). 1:1,774,080. Chicago: Shell Oil Company. Retrieved April 1, 2015 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- 1 2 "Google Maps". Google, Inc. Retrieved 10 September 2018. - Used distance measuring tool on old US 80 segments.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Towne, Douglas (August 2018). "The "Other" Road". Article. Phoenix Magazine. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ Arizona Highway Department; W.M. DeMerse (1935). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). Phoenix, Arizona: Arizona Highway Department. Retrieved April 30, 2015 – via Arizona Roads.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shell Oil Company; H.M. Gousha Company (1956). Shell Highway Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,330,560. Chicago: Shell Oil Company. Retrieved March 31, 2015 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jensen, Jeff (2013). Drive the Broadway of America!. Tucson, Arizona: Bygone Byways. ISBN 9780978625900.

- 1 2 Staff. "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1939-P-447". Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Shell Oil Company; H.M. Gousha Company (1951). Various Regions and Cities in Arizona and New Mexico (Map). Scale not given. Chicago: Shell Oil Company. Retrieved April 1, 2015 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- ↑ Boggs, Johnny (2016-05-23). "On the Old Gila Trail". True West Magazine. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- ↑ 1906-1956., Corle, Edwin, (1964). The Gila : river of the Southwest. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803250401. OCLC 39248974.

- ↑ "Arizona Hazardous Waste Facility: Environmental Impact Statement". San Francisco, California: Environmental Protection Agency. January 1983: L-1.L-2. Retrieved 2018-08-24 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 "Arizona History". Office of the Arizona Governor. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Broyles, Bill (2012). Last Water on the Devil's Highway : a Cultural and Natural History of Tinajas Altas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 104. ISBN 0816598878. OCLC 873761384.

- 1 2 3 Stanley, John (February 9, 2012). "Territory of Arizona Established". Arizona Central. Phoenix. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ "The Mexican Cession". United States History. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Hague, Harlan (7 December 2000). "The Search for a Southern Overland Route to California": 2-. Retrieved 2018-08-25 – via California Department of FIsh and Wildlife.

- ↑ Keane, Melissa; Brides, J. Simon (May 2003). "Good Roads Everywhere" (PDF). Cultural Resource Report Report. Arizona Department of Transportation. pp. 43, 60. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ McDaniel, Chris (29 May 2011). "Ocean To Ocean Bridge critical link between shores". News Article. Yuma Sun. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Weingroff, Richard F. (October 17, 2013). "U.S. Route 80: The Dixie Overland Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Laskow, Sarah. "Resurrecting the Original Road Trip on Americas' Ghost Highway". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ↑ Fraser, Clayton B. (July 2006). "Historic American Engineering Record: Gillespie Dam Bridge" (PDF): 14–16 – via National Park Service Santa Fe Support Office.

- ↑ Rand McNally and Company (1924). Rand McNally Auto Trails Map of Arizona and New Mexico (Map). 1:2,290,000. Chicago: Rand McNally and Company. Retrieved April 1, 2015 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- ↑ Rand McNally and Company (1925). Rand McNally Auto Trails Map of Arizona and New Mexico (Map). 1:1,393,920. Chicago: Rand McNally and Company. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- 1 2 3 State of Arizona (31 October 2004). "Historic Property Inventory Forms - Pima Bridges" (PDF). Inventory Records. Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT). Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads & American Association of State Highway Officials (November 11, 1926). United States System of Highways Adopted for Uniform Marking by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). 1:7,000,000. Washington, DC: United States Geological Survey. OCLC 32889555. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2016 – via University of North Texas Libraries.

- 1 2 "Historic Gillespie Dam". Gila Bend Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Arizona Highway Department (1928). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,584,000. Phoenix: Arizona Highway Department. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Arizona Highway Department (1930). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,267,200. Taylor Printing Company. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ State of Arizona (31 October 2004). "Historic Property Inventory Forms - Maricopa Bridges" (PDF). Inventory Records. Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT). Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Arizona Highway Department (1935). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,267,200. Taylor Printing Company. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Arizona Highway Department (1946). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,267,200. Taylor Printing Company. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Fischer, Howard (2017-10-17). "Jefferson Davis Highway 'no longer exists' in Arizona — but its marker will stay". Arizona Daily Star. Capitol Media Services. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- 1 2 3 Clinco, Demion (May 2016). "Historic Arizona U.S. Route 80 Historic Highway Designation Application" (PDF). Application Document. Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation. p. 251. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Public Roads Administration (August 14, 1957). Official Route Numbering for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways as Adopted by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). Scale not given. Washington, DC: Public Roads Administration. Retrieved April 4, 2012 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Pry, Mark; Andersen, Fred (December 2011). "Arizona Transportation History" (PDF). Technical Report. Arizona Department of Transportation. pp. 61–67. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Staff. "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1948-P-065". Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Clinco, Demion (18 February 2009). "Historic Miracle Mile: Tucson's Northern Auto Gateway" (PDF). Historic Context Study Report. Frontier Consulting. pp. 31, 32. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ "State To Hold First Superhighway Hearing Under New U.S. Law Dec. 6". The Arizona Republic. 67 (81 ed.). Phoenix, Arizona. Associated Press. 1956-11-16. p. 21. Retrieved 2018-09-07.

- 1 2 "Federally Aided Road Improvements Begin". Arizona Daily Star. 116 (85) (Morning ed.). Tucson, Arizona: Newspapers.com. 1957-03-26. p. 1. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- 1 2 3 Harelson, Hugh (1960-12-04). "$3 Million Road Budget Explained". Arizona Republic. 71 (99). Phoenix, Arizona: Newspapers.com. p. 17. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- ↑ Arizona Highway Department; Rand McNally Company (1958). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,520,640. Phoenix: Arizona Highway Department. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Arizona Highway Department; Rand McNally Company (1963). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,520,640. Phoenix: Arizona Highway Department. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Arizona Department of Transportation (1971). ADOT Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,267,200. Phoenix: Arizona Highway Department. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- 1 2 Staff. "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1977-11-A-029". Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- ↑ Staff. "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1989-12-A-096". Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ Toll, Eric J. (2 November 2015). "Interstate 10 completed; I-11 construction begins". Phoenix, Arizona. Phoenix Business Journal. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Historic Arizona U.S. Route 80 Designation". Webpage. Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation. August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ Davis, Shaq (2018-09-21). "Arizona's portion of U.S. Route 80, opened in 1926, wins 'Historic Road' status". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson, Arizona: Tucson.com. Retrieved 2018-09-21.

- ↑ Arizona Department of Transportation (2014). "Arizona Parkways, Historic and Scenic Roads" (PDF). Phoenix: Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- 1 2 "Tucson's Miracle Mile listed in the National Register of Historic Places". Webpage. Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation. December 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Rand McNally and Company; Valley National Bank of Arizona (1950). Map of Greater Tucson and Surrounding Area (Map). 1:33,580. San Francisco: Valley National Bank of Arizona. Retrieved September 9, 2018 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- ↑ "NETRonline: Historic Aerials - Viewer". NETR Online. Tempe, Arizona: Nationwide Environmental Title Research, LLC. 2018-09-10. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ↑ "Gila Bend, AZ: Stovall's Spage Age Lodge". Roadside America. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Horseshoe Cafe and Bakery: Benson, AZ". Yelp. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ "O.K. Corral Famous Gunfight Site, Tombstone Arizona". O.K. Corral. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ "History". Queen Mine Tours. 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

External links

- Map of US 80 in Arizona circa 1951 - OpenStreetMap

- U.S. Highway 80 at American Roads

- Bygone Byways - Includes several resources related to US 80 in Arizona

- Old Spanish Trail Centennial- historical re-enactment http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/home.html

| Previous state: California |

Arizona | Next state: New Mexico |

Route map: