Rail gauge in Australia

| Track gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By transport mode | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tram · Rapid transit Miniature · Scale model |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By size (list) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change of gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Break-of-gauge · Dual gauge · Conversion (list) · Bogie exchange · Variable gauge |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By location | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

North America · South America · Europe · Australia  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

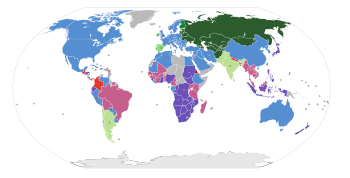

Rail gauges in Australia display significant variations, which has presented an extremely difficult problem for rail transport on the Australian continent for over 150 years. As of 2014, there is 11,801 kilometres (7,333 mi) of narrow-gauge railways, 17,381 kilometres (10,800 mi) of standard gauge railways and 3,221 kilometres (2,001 mi) of broad gauge railways.

In the 19th century, each of the Colonies of Australia adopted their own gauges. However, with Federation in 1901 and the removal of trade barriers, the short sightedness of three gauges became apparent. It would be 94 years before all mainland state capitals were joined by one standard gauge.

Rail gauges and route kilometres

The most common railway gauges in Australia are narrow (1,067 mm or 3 ft 6 in), standard (1,435 mm or 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in standard gauge) and broad (1,600 mm or 5 ft 3 in) gauges. The narrower 610 mm or 2 ft gauge is found on shorter lines, particularly sugarcane tramways in Queensland.

As of 2014, the Australian rail network could be broken down in kilometres as:[1]

| State or Territory |

Narrow | Standard | Broad | Dual | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queensland | 7,583 | 67 | 84 | 4 | 7,739 | |

| New South Wales | 8 | 7,071 | 73 | 1 | 7,153 | |

| Australian Capital Territory | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Victoria | 16 | 1,222 | 2,894 | 32 | 28 | 4,192 |

| Tasmania | 667 | 667 | ||||

| South Australia | 828 | 3,114 | 253 | 22 | 4,217 | |

| Northern Territory | 3 | 1,690 | 1,693 | |||

| Western Australia | 2,963 | 4,211 | 207 | 7,381 | ||

| Total | 11,801 | 17,381 | 3,221 | 346 | 35 | 33,052 |

- In Queensland, there is a 4,000 kilometre Sugarcane tramways network, 18 lines on 610 mm (2 ft) and one on 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in), but these carry very little through traffic so that the break-of-gauge is not a problem.[2]

- Victoria had five short 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) lines for general traffic[3]

- Private timber tramways used a variety of gauges

- Lines built in association with iron ore mining in the Pilbara, bauxite mining in Weipa and steel manufacturing at Newcastle and Port Kembla have all used standard gauge lines. Likewise the Richmond Valley and South Maitland Railway lines in the Hunter Valley also used standard gauge.

- The Whyalla Steelworks was built as a narrow line, being converted to standard gauge when the Commonwealth Railways Whyalla line opened.

- Temporary lines at construction sites, such as the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge railways used for the development of the national capital at Canberra between 1913 and 1927, including Parliament House and 2 ft (610 mm) construction line to Burrinjuck Dam

History

Pre-construction uniformity

In 1845, a Royal Commission on Railway Gauges in the United Kingdom was formed to report on the desirability for a uniform gauge.[4] As a result, the Regulating the Gauge of Railways Act 1846 was passed which prescribed the use of 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) in England, Scotland and Wales (with the exception of the Great Western Railway) and 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) in Ireland.

In 1846, Australian newspapers discussed the break of gauge problem in the United Kingdom, especially for defence.[5][6][7] In 1847, South Australia adopted the 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) gauge as law.[8]

In 1848, Governor of New South Wales, Charles Fitzroy, was advised by Secretary of State for the Colonies in London, Earl Grey, that one uniform gauge should be adopted in Australia, this being the British standard 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) gauge. The recommendation was adopted by the then three colonies.[9][10][11] Grey notes in his letter that South Australia has already adopted this gauge.[12]

At this stage Victoria and Queensland were still part of New South Wales.

Since the Australian Overland Telegraph Line and under-sea cable communications with England did not open until 1872, communications between Britain and Australia before then were hampered by having to be conducted via sailing ship. The journey varied from about seven months on slower ships to about two and a half months on fast clipper ships.[13] This had particular consequences for the selection of railway gauge in Australia.

Origins of the gauge muddle

At that time the private Sydney Railway Company had begun planning its railway line to Parramatta. The chief engineer of the company was Irish-born Francis Webb Sheilds. After his appointment in 1849, Shields initially stated a preference for 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm)[14] but in 1850 he persuaded the company, which in turn asked the NSW legislature, to change to the Irish standard gauge of 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm). This decision was endorsed by the NSW Governor, and Colonial Secretary Earl Grey in London agreed in 1851.[15]

However, Sheilds and his three subordinates resigned in December 1850 when the company cut their salaries for financial reasons. After the interim appointment of Henry Mais, in July 1852 the company selected a new Scottish engineer, James Wallace, who preferred the British standard gauge. The Government was persuaded to make the change back to 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) and in January 1853 they advised the company that the Act requiring 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) would be repealed.

In February 1853 the other colonies (Victoria having separated from New South Wales in 1851) were sent a memorandum advising them of the pending change and recommended they likewise adopt 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm).[16] In Victoria the memorandum was distributed to three railway companies and their responses were sought, with two replying and only one showing a distinct preference for 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm). However the Melbourne and Hobson's Bay Railway Company asked for a determination from the government as it had prepared plans for both gauges and was due to send an order for locomotives and rolling stock to England by boat at the start of April. In reply at the end of March, the companies were told the colonial Victorian government preferred 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) and the order was subsequently placed.

In July 1853, the Government of Victoria advised New South Wales that it would use the broader gauge and later appealed to the British Government to force a reversal of New South Wales' decision.[17] Subsequently, the Melbourne and Hobson's Bay Railway Company opened the first railway in Australia in 1854, as a 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) broad gauge line, and the South Australian Railways used the same gauge on its first steam-hauled railway in 1856.

Despite a request by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to reconsider this alteration, in 1855 the NSW Governor William Denison gave the go-ahead for the 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) Sydney to Parramatta railway, which opened in September of that year.[18][19]

Concerns over the gauge difference began to be raised almost immediately. At a Select Committee called in Victoria in September 1853, a representative of the railway company which had not replied to Charles La Trobe's earlier memorandum, reported a preference for 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm), but when asked if Victoria should follow NSW he answered: "We must, I conclude of necessity, do so".[20] In 1857, the NSW railway engineer John Whitton suggested that the short length of railway then operating in New South Wales be altered from 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) gauge to 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) to conform with Victoria but, despite being supported by the NSW Railway Administration, he was ignored.[21] At that time there were only 23 miles (37 km) of track, four engines and assorted cars and wagons on the railway. However, by 1889, New South Wales, under engineer Whitton, had built almost 1,950 miles (3,500 km) of standard gauge line.[18]

Extension of the gauge muddle

The 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow gauge was introduced to Australia in 1865, when the Queensland Railways opened its first railway from Ipswich to Grandchester. The gauge was chosen on the supposition that it would be constructed more cheaply, faster and on tighter curves than the wider gauges.[22] This was the first narrow gauge main line in the world.

South Australia first adopted this gauge in 1867 with its line from Port Wakefield to Hoyleton.[23] J. T. Bagot was one of the advocates. The main reasons for choosing this were reduced cost, and the expectation that the narrow gauge would never connect to broad gauge lines. Overbuilt English railways were criticised. The Wakefield line was also envisaged as a horse-drawn tramway.[24]

Later narrow gauge lines went towards Broken Hill and to Oodnadatta[25] and from Mount Gambier. The Port Lincoln system was always isolated by geography.

The Western Australian Government Railways adopted it in 1879 for its first line from Geraldton to Northampton.[18]

The Tasmanian Government Railways opened its first railway from Launceston to Deloraine in 1871 using 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) broad gauge, but converted to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow gauge in 1888.[18]

Towards a network

Until the 1880s the gauge issue was not a major problem, as there were no connections between the separate systems. The focus of railway traffic was movement from the hinterland to the ports and cities on the coast so governments were not concerned about the future need for either inter-city passenger or freight services.[26] It was not until 1883 when the broad and standard gauge lines from Melbourne and Sydney met at Albury, and in 1888 narrow and standard gauge from Brisbane and Sydney met at Wallangarra that the break of gauge became an issue.[27] The issue of rail gauge was mentioned in an 1889 military defence report authored by English army officer Major General James Bevan Edwards, who said that the full benefit of the railways would not be attained until a uniform gauge was established. It needs to be remembered, however, that until federation the benefits of a uniform gauge were not immediately apparent, as passengers would have to pass through customs and immigration at the intercolonial border, meaning that all goods would have to be removed for customs inspection. It was only with Federation in 1901, and the introduction of free trade between the states, that the impediment of different gauges became apparent.

At the time of Federation, standard gauge was used in only NSW, but was favoured for further work. Work on gauge conversion was assisted by section 51 (xxxiii) of the Constitution of Australia, which made specific provisions for the Commonwealth Parliament to make laws with respect to railway acquisition and construction. An agreement was made with the South Australian and Western Australian state governments for the Trans-Australian Railway from Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie, with work started in 1911 and completed in 1917.[27] However, with the different gauges, to ship goods from Queensland to Perth required four transhipments.

In 1921 a royal commission into rail gauge was delivered, recommending gauge conversion of large areas of the country. It stated "that the gauge of 4-ft. 8.5-in. be adopted as the standard for Australia; that no mechanical, third rail, or other device would meet the situation, and that uniformity could be secured by one means only, viz., by conversion of the gauges other than 4-ft. 8.5-in."[28] Following the royal commission, agreements were made for the standard gauge NSW North Coast line to be extended from Kyogle to South Brisbane (completed in 1930) and for the Trans-Australian Railway to be extended from Port Augusta to Port Pirie (completed 1937).[27]

By the outbreak of World War II in 1939, there were 13 break-of-gauge locations, with upwards of 1,600 service personnel and many more civilians employed to transfer 1.8 million tons of freight during the period. The breaks of gauge were at:[27]

| Location | State | Narrow | Standard | Broad |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Brisbane | Queensland | x | x | |

| Wallangarra | Queensland | x | x | |

| Albury | New South Wales | x | x | |

| Oaklands | New South Wales | x | x | |

| Tocumwal | New South Wales | x | x | |

| Broken Hill | New South Wales | x | x | |

| Mount Gambier | South Australia | x | x | |

| Serviceton | South Australia | x | x | |

| Terowie | South Australia | x | x | |

| Peterborough | South Australia | x | x | x |

| Gladstone | South Australia | x | x | x |

| Port Pirie | South Australia | x | x | x |

| Port Augusta | South Australia | x | x | |

| Kalgoorlie | Western Australia | x | x | |

- Hamley Bridge ceased to be a break of gauge point in 1927 when the broad gauge was extended to Gladstone[29]

- South Brisbane ceased to be a break of gauge point when the NSW North Coast line was extended over the Merivale Bridge to Roma Street in 1986

- Acacia Ridge was developed as a break-of-gauge yard in Brisbane in the 1970s to relieve overcrowding at Clapham goods station, which is opposite the Moorooka passenger station.

- The NSW North Coast line from Acacia Ridge to Bromelton was dual gauged in 2009 as part of the Nucleus Transmodal Hub to relieve overcrowding at Acacia Ridge[30]

Break-of-gauge devices

In 1922, 273 inventions to solve the break-of-gauge had been rejected, and none adopted.[31] In 1933, as many as 140 devices were proposed by inventors to solve the break-of-gauge problem, none of which were adopted.[32]

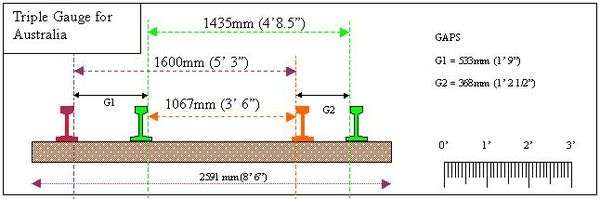

Even dual gauge with a third rail for combining Irish gauge and standard gauge was rejected as too reckless, as the gap between these gauges of 6.5 in (170 mm) was considered to be too small.[33] Dual gauge combining Irish gauge and narrow gauge where the gap was 21 in (530 mm) was also rejected.[34]

Opposition to a third rail

While Prime Minister Billy Hughes had expressed support for the idea of a third rail solving the break of gauge difficulty, the predominant opinion of senior officers of the railways was to oppose it.[35]

Clapp Report

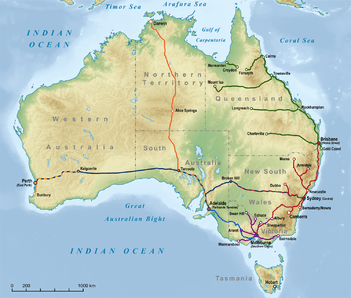

thin lines – 3' 6" (1067mm)

dotted lines – 4' 8.5" (1435mm)

dashed thick lines – new 4' 8.5"

thick lines – 5' 3" (1600mm)

After the wartime experience, a report into the Standardisation of Australia's rail gauges was completed by former Victorian Railways Chief Commissioner Harold Clapp for the Commonwealth Land Transport Board in March 1945. It included three main proposals:[27]

- Gauge standardisation from Fremantle and Perth to Kalgoorlie, all of South Australian and Victorian broad gauge lines, all of the South Australian south east and Peterborough division narrow gauge lines, and acquisition and conversion of the Silverton Tramway. Costed at £44.3 million.

- New standard gauge "strategic and developmental railway" from Bourke, New South Wales to Townsville, Queensland and Dajarra (near Mount Isa) with new branch lines from Bourke via Barringun, Cunnamulla, Charleville, Blackall to Longreach. Existing narrow gauge lines Queensland would also be gauge converted, including Longreach – Linton – Hughenden – Townsville Dajarra and associated branches. Costed at £21.6 million.

- New standard gauge line to Darwin, including new line from Dajarra, Queensland to Birdum, Northern Territory, and gauge conversion of the Birdum to Darwin narrow gauge line. Costed at £10.9 million.

The report wrote that if only main trunk lines were converted, it would introduce a multitude of break of gauge terminals and result in greatly increased costs. It also recommended abandoning part of the existing Perth to Kalgoorlie narrow gauge line, and build a flatter and straighter route using third rail dual gauge, as modernisation was just as important as standardisation.[36]

South Australia was unhappy with the report, as the link to the Northern Territory would not run through its state. Western Australia and Queensland both saw no advantage in the report, as they already had a common gauge in their states, and only one main break of gauge. NSW entered into the agreement to advance gauge standardisation in Victoria and South Australia, but did not ratify it.[36]

Gauge conversion did continue, with the South Australian Railways' Mount Gambier line from Wolseley to Mount Gambier and associated branches converted to broad gauge in the 1950s, on the understanding it would again to standard gauge at a later date making it the first ever only railway in Australia to have successfully been converted to all three gauges. Standard gauge lines were also built, with the line between Stirling North and Marree opened in July 1957.[36]

Wentworth Committee

In 1956 a Government Members Rail Standardisation Committee was established, chaired by William Wentworth MP.[37] It found that while there was still considerable doubt as to the justification for large scale gauge conversion, there was no doubt that work on some main trunk lines was long overdue. Both the committee and the government strongly supported three standardisation projects at a cost of £41.5 million:

- Albury to Melbourne (priority 1)

- Broken Hill to Adelaide via Port Pirie (priority 2, built 3rd)

- Kalgoorlie to Perth and Fremantle (priority 3, built 2nd)

The Commonwealth, NSW and Victorian governments were first to start work, with the first freight train operating on the converted North East line to Melbourne operating in January 1962 and the first through passenger train in April 1962. Over the next 12 months net freight tonnage was up 32.5% and to 1973 there was an average increase of 8.6%.[37]

The work in Western Australia was predicated by an agreement entered into in November 1960 between the State Government and BHP for a standard gauge line to be built to allow iron ore from Koolyanobbing to be shipped to a new steel mill at Kwinana. A new dual gauge line was built through the Avon Valley from Midland to Northam on 1 in 200 grades instead of 1 in 40;[21] and a new line was built from Southern Cross to Kalgoorlie though Koolyanobbing.[37] The first wheat train ran from Merredin to Fremantle in November 1966 and the first iron ore train from Koolyanobbing to Kwinana in April 1967, with the line opened in full in August 1969. Kalgoolie to Perth freight train times were reduced from 31 hours to 13 hours, and passenger train times from 14 hours to eight hours. A new line was built from Woodbridge to Kwinana and one of the tracks on the Fremantle line converted to dual track from Cockburn Junction to Fremantle Harbour.[38] The Midland line in Perth was converted to dual gauge and a new terminus station built.

In November 1971, following the discovery of rich nickel deposits, work commenced on converting the 640 kilometre line from Leonora to Esperance including 90 kilometres of track on a new alignment. The work was completed in September 1974.[38]

In South Australia work on Port Pirie to Broken Hill did not start until 1963. The narrow gauge lines from Gladstone and Peterborough were not converted, with triple gauge yards provided. Standard gauge access to Adelaide was not provided.[37] From Cockburn to Broken Hill a new railway was built on an improved alignment, avoiding the private Silverton Tramway route.[39] The completion of this link enabled the first Indian Pacific to run across the nation in March 1970 from Sydney to Perth.

Whitlam Government

A new line between Tarcoola and Alice Springs was given the go ahead by the Whitlam Government in 1974. Built to replace the narrow gauge Central Australia Railway, the 831 kilometre long line was completed in 1980.[40]

Work on standard gauge access to Adelaide started in 1982, with conversion of the broad gauge south of Red Hill, a new line north of there to Crystal Brook where it met the standard gauge line from Port Pirie to Broken Hill. Freight trains began using the line in 1983 with passenger trains following the next year when Keswick Terminal opened. With benefits exceeding the cost by 2.8 times over 25 years, Australian National was able to obtain a loan for the funding of the work.[39]

One Nation project

As part of the Keating Government's One Nation project, the Melbourne-Adelaide railway line was converted to standard gauge in 1995.[41][42] The Hopetoun, Portland and Yaapeet lines in Victoria, and the Pinnaroo, Loxton and Apamurra lines in South Australia were also gauge converted. The remaining isolated broad gauge and narrow gauge lines were closed with the Mount Gambier and Mount Barker lines being the most controversial.[43] The Fishermans Island line was converted to dual gauge in 1997 to serve the Port of Brisbane.[41]

Recent projects

Gauge conversion of 2,000 kilometres of track in Victoria was announced by the State Government in May 2001 but did not proceed due to the difficulty of achieving any agreement with then track manager, Freight Australia.[42][44] In 2010, 200 kilometres of the North East line in Victoria was gauge converted between Seymour and Albury.[45] In the same year standard gauge access was provided to the Port of Geelong, 13 years after the conversion to standard gauge of the Western standard gauge line between Melbourne and Adelaide, which runs through the northern suburbs of Geelong.[46]

The Oaklands branch line was converted in 2009 to standard gauge as part of the project to standardise the North East line, to prevent that branch becoming isolated.[47]

To allow the creation of the Nucleus Transmodal Hub at Bromelton, Queensland, the Acacia Ridge to Bromelton section of the NSW North Coast line was converted to dual gauge in 2009, however has yet to be used.[30]

In November 2012, Brookfield Rail completed an upgrade on the Morawa to Geraldton line with gauge convertible sleepers installed to allow for conversion in the future.[48][49]

Future projects

In Adelaide, the Belair, Gawler and Outer Harbor lines have been relaid with gauge convertible sleepers with it planned to gauge convert the entire Adelaide Metro network in the future.[50][51]

In Victoria, the Mildura line was scheduled to be converted in 2016.[52] However, the project was put on hold to be completed as part of the Murray Basin Rail Project.[53] The standardisation of the remaining North East lines (including Shepparton/Tocumwal and Deniliquin) was a recommendation by Infrastructure Victoria as a future project in its 30 Year Infrastructure Strategy[54]

References

- ↑ Trainline 2 Statistical Report Bureau of Infrastructure Transport & Regional Economics 2014 page 53

- ↑ Queensland suger cane railways today Light Rail Research Society of Australia

- ↑ VR timeline Mark Bau's VR website

- ↑ "The Proposed Railroad". The South Australian. Adelaide. 12 December 1845. p. 3. Retrieved 6 November 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Army and Navy". South Australian Register. Adelaide. 24 June 1846. p. 4. Retrieved 25 October 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The South Australian Register". South Australian Register. Adelaide. 8 August 1846. p. 2. Retrieved 25 October 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Court of Common Council". Sydney Morning Herald. 21 August 1846. p. 3. Retrieved 25 October 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the Legislative Council". The South Australian. Adelaide. 8 October 1847. p. 3. Retrieved 8 January 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Break of Gauge". The Argus. Melbourne. 8 April 1911. p. 6. Retrieved 30 November 2010 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Maitland Mercury". The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser. Maitland. 20 June 1849. p. 2. Retrieved 6 November 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Legislative Council". South Australian Register. Adelaide. 20 February 1850. p. 3. Retrieved 27 August 2011 – via National Library of Australia. 4' 8.5" Gauge in Adelaide

- ↑ "Colonial Railways". Sydney Morning Herald. 15 June 1849. p. 3. Retrieved 19 October 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The journey to Australia". Gold. Special Broadcasting Service Australia. 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ Mills (2006), p.99

- ↑ Laird, p 185

- ↑ Mills (2006), p.91-111

- ↑ Mills (2006), p.125-129

- 1 2 3 4 Laird, p 186

- ↑ Harrigan, Leo J. (1962). Victorian Railways to ‘62. Melbourne: Victorian Railways Public Relations and Betterment Board.

- ↑ Mills(2006), p.127

- 1 2 "The Conversion to Standard Gauge". Technology in Australia 1788–1988. www.austehc.unimelb.edu.au. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ↑ Pollard, Neville (February 2014). "Australian's Uniform Gauge Debacle, Part 1". Australian Railway History. Vol. 65 no. 916. p. 4.

- ↑ "THE PARLIAMENT". The South Australian Advertiser. 9 January 1867. p. 3. Retrieved 19 April 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "THE PARLIAMENT". The Express and Telegraph. V (1, 214). South Australia. 13 December 1867. p. 2 (LATE EDITION.). Retrieved 19 April 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Evans, John (April 2014). "The Uniform Gauge Question: A South Australian Perspective". Australian Railway History. Vol. 65 no. 918. p. 5.

- ↑ "Factors Impeding Developments". Technology in Australia 1788–1988. www.austehc.unimelb.edu.au. p. 375. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Laird, p 187

- ↑ "Standardisation of Railway Gauges". Year Book Australia, 1967. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 25 January 1967. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ↑ The Big Push The Register 1 August 1927

- 1 2 The $55.8 million dual gauge rail line from Acacia Ridge to Bromelton remains unfinished Quest Newspapers 10 November 2014

- ↑ "Break of Gauge". The Daily News. Perth. 12 January 1922. p. 2. Retrieved 26 October 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Break of Gauge". The Brisbane Courier. Brisbane. 14 August 1933. p. 15. Retrieved 27 August 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Great Western Railway". The Argus. Melbourne. 11 March 1926. p. 7. Retrieved 26 August 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Standard Gauge Plan Postponed". The Argus. Melbourne. 17 February 1941. p. 5. Retrieved 26 August 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Uniform Gauge". The North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times. Tasmania. 1 June 1916. p. 3. Retrieved 27 October 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 3 Laird, p 188

- 1 2 3 4 Laird, p 189

- 1 2 Westrail A concise history. Westrail. 1981. pp. 8, 13.

- 1 2 Laird, p 190

- ↑ "Tarcoola-Alice Springs Railway". Technology in Australia 1788–1988. www.austehc.unimelb.edu.au. p. 379. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- 1 2 Laird, p 191

- 1 2 John Hearsch (1 February 2007). "Victoria's Regional Railway Past, Present and Potential" (PDF). RTSA Regional Rail Symposium, Wagga Wagga. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ↑ Evans, John (April 2014). "The Uniform Gauge Question: A South Australian Perspective". Australian Railway History. Vol. 65 no. 918. pp. 3–10.

- ↑ Rail Gauge Standardisation Project Audito General Victoria August 2006

- ↑ "$500m rail link upgrade for Victoria". news.ninemsn.com.au. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ↑ "Corio Independent Goods Line Guide". Rail Geelong. www.railgeelong.com. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ↑ Rail Safety Investigation Report Derailment of El Zorro Grain Service 5CM7 Rennie 3 January 2013 Office of Rail Safety Investigations

- ↑ The MidWest Rail Upgrade Brookfield Rail

- ↑ Mixed fortunes for Western Australian projects International Railway Journal 16 November 2012

- ↑ Belair Line Renewal Department of Transport, Planning & Infrastructure

- ↑ Gawler Rail Revitalisation Department of Transport, Planning & Infrastructure

- ↑ Murray Region gauge conversion to begin next year Railway Gazette International 28 August 2015

- ↑ https://www.ptv.vic.gov.au/projects/rail-projects/murray-basin-rail-project

- ↑ http://www.infrastructurevictoria.com.au/sites/default/files/images/IV%2030%20Year%20Strategy%20WEB%20V2.PDF

Further reading

- John Ayres Mills (2006): The Myth of the Standard Gauge: Rail Gauge Choice in Australia, 1850-1901

- John Ayres Mills (2010): Australia's mixed gauge railway system: a reassessment of its origins.

- Philip Laird (2001). Australia's gauge muddle and prospects. Back on Track: Rethinking Transport Policy in Australia and New Zealand. UNSW Press. ISBN 0-86840-411-X. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- Brady, I.A. (1971) A Brief History of Standard Gauge in Australia Brady I. A. Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, May;June, 1971 pp98–120;131-139