Suwannee River

| Suwannee | |

| River | |

Suwannee River, Florida | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Santa Fe River |

| - right | Alapaha River, Withlacoochee River |

| Cities | Fargo, Georgia, White Springs, Florida, Branford, Florida |

| Source | Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge |

| - location | Fargo, Georgia |

| Mouth | Gulf of Mexico |

| - location | Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge, Suwannee, Florida |

| - elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| - coordinates | 29°17′18″N 83°9′57″W / 29.28833°N 83.16583°WCoordinates: 29°17′18″N 83°9′57″W / 29.28833°N 83.16583°W |

| Length | 246 mi (396 km) |

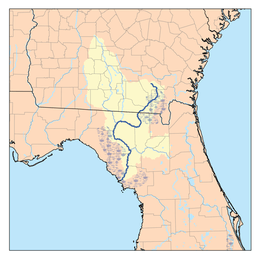

Suwannee River Drainage Basin | |

The Suwannee River (also spelled Suwanee River) is a major river that runs through South Georgia southward into Florida in the southern United States. It is a wild blackwater river, about 246 miles (396 km) long.[1] The Suwannee River is the site of the prehistoric Suwanee Straits which separated peninsular Florida from the panhandle.

Geography

The headwaters of the Suwanee River are in the Okefenokee Swamp in the town of Fargo, Georgia. The river runs southwestward into the Florida Panhandle, then drops in elevation through limestone layers into a rare Florida whitewater rapid. Past the rapid, the Suwanee turns west near the town of White Springs, Florida, then connects to the confluences of the Alapaha River and Withlacoochee River.

Starting at the confluences of those three rivers, that confluence forms the southern borderline of Hamilton County, Florida. The Suwanee then bends southward near the town of Ellaville, Florida, followed by Luraville, Florida, then joins together with the Santa Fe River (Florida) from the east, south of the town of Branford, Florida.

The river ends and drains into the Gulf of Mexico on the outskirts of Suwannee, Florida.

Etymology

The Spanish recorded the native Timucua name of Guacara for the river that would later become known as the Suwannee. Different etymologies have been suggested for the modern name.

- San Juan: D.G. Brinton first suggested in his 1889 Notes on the Floridian Peninsula that Suwannee was a corruption of the Spanish San Juan.[2] This theory is supported by Jerald Milanich, who states that "Suwannee" developed through "San Juan-ee" from the 17th-century Spanish mission of San Juan de Guacara, located on the Suwannee River.[3]

- Shawnee: The migrations of the Shawnee (Shawnee: Shaawanwaki; Muscogee: Sawanoke) throughout the South have also been connected to the name Suwannee. As early as 1820, the Indian agent John Johnson said "the 'Suwaney' river was doubtless named after the Shawanoese [Shawnee], Suwaney being a corruption of Shawanoese."[4] However, the primary southern Shawnee settlements were along the Savannah River, with only the village of Ephippeck on the Apalachicola River being securely identified in Florida, casting doubt on this etymology.

- "Echo": In 1884, Albert S. Gatschet claimed that Suwannee derives from the Creek word sawani, meaning "echo", rejecting the earlier Shawnee theory.[5] Stephen Boyd's 1885 Indian Local Names with Their Interpretation [6] and Henry Gannett's 1905 work The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States repeat this interpretation, calling sawani an "Indian word" for "echo river".[7] Gatschet's etymology also survives in more recent publications, often mistaking the language of translation. For example, a University of South Florida website states that the "Timucuan Indian word Suwani means Echo River ... River of Reeds, Deep Water, or Crooked Black Water".[8] In 2004, William Bright repeats it again, now attributing the name "Suwanee" to a Cherokee village of Sawani, which is unlikely as the Cherokee never lived in Florida or South Georgia.[9] This etymology is now considered doubtful: 2004's A Dictionary of Creek Muscogee does not include the river as a place-name derived from Muscogee, and also lacks entries for "echo" and for words such as svwane, sawane, or svwvne, which would correspond to the anglicization "Suwannee".[10]

History

The Suwannee River area has been inhabited by humans for thousands of years. During the first millennium CE, it was inhabited by the people of the Weedon Island archaeological culture, and around 900 CE, a derivative local culture, known as the Suwanee River Valley culture, developed.

By the 16th century, the river was inhabited by two closely related Timucua language-speaking peoples: the Yustaga, who lived on the west side of the river; and the Northern Utina, who lived on the east side.[11] By 1633, the Spanish had established the missions of San Juan de Guacara, San Francisco de Chuaquin, and San Augustin de Urihica along the Suwannee to convert these western Timucua peoples.[12]

In the 18th century, Seminoles lived by the river.

The steamboat Madison operated on the river before the Civil War, and the sulphur springs at White Springs became popular as a health resort, with 14 hotels in operation in the late 19th century.

Music

This river is the subject of the Stephen Foster song "Old Folks at Home", in which he calls it the Swanee Ribber. Foster had named the Pedee River of South Carolina in his first lyrics. It has been called Swanee River because Foster had used an alternative contemporary spelling of the name.[13] Foster never actually saw the river he made world-famous.

George Gershwin's song, with lyrics by Irving Caesar, and made popular by Al Jolson, is also spelled "Swanee" and boasts that "the folks up North will see me no more when I get to that Swanee shore".

Both of these songs feature banjo-strumming and reminiscences of a plantation life more typical of 19th-century South Carolina than of among the swamps and small farms in the coastal plain of south Georgia and north Florida.

Don Ameche starred as Foster in the fictional biographical film Swanee River (1939).

When approaching the Suwannee River via several major highways, motorists are greeted with a sign which announces they are crossing the Historic Suwannee River, complete with the first line of sheet music from "Old Folks at Home". This is Florida's state song, designated as such in 1935.

In 2008, its original lyrics were replaced[14] with a politically correct version.[15] There is a Foster museum and carillon tower at Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center State Park in White Springs. The spring itself is called White Sulphur Springs because of its high sulphur content. Since there was a belief in the healing qualities of its waters, the Springs were long popular as a health resort.

The idiom "up the Swannee" or "down the swanny" means something is going badly wrong, analogous to "up the creek without a paddle".

Recreation

A unique aspect of the Suwannee River is the Suwannee River Wilderness Trail, a cooperative effort by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the Suwannee River Water Management District, and the cities, businesses, and citizens of the eight-county Suwannee River Basin region. The boating route encompasses 170 river miles (274 river kilometers), from Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center State Park to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Florida National Scenic Trail runs along the Suwannee River's western banks for approximately 60 miles (97 km), from Deep Creek Conservation Area in Columbia County to Twin Rivers State Forest in Madison County.

The Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge offers bird and wildlife observation, wildlife photography, fishing, canoeing, hunting, and interpretive walks. A driving tour is under construction, and several boardwalks and observation towers offer views of wildlife and habitat.

In recent years, the Suwannee River has been the site of many music gatherings. Magnolia Festival, SpringFest, and Wanee have been held annually in Live Oak, Florida, at the Spirit of the Suwannee Music Park, adjacent to the river. Performing artists have included Vassar Clements, Peter Rowan, David Grisman, Allman Brothers Band, and the String Cheese Incident.

Crossings

See also

Notes

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed April 18, 2011

- ↑ Brinton, Daniel; Brinton, Garrison Brinto Daniel Garrison (2016-10-10). Notes on the Floridian Peninsula. Applewood Books. ISBN 9781429022637.

- ↑ Milanich:12-13

- ↑ Johnson, Byron A. "THE SUWANNEE - SHAWNEE DEBATE" (PDF). Florida Anthropologist. 25 (2, pt. 1, June 1972): 67.

- ↑ Gatschet, Albert Samuel (1884-01-01). A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians. D.G. Brinton.

- ↑ Boyd, Stephen G. (1885-01-01). Indian Local Names with Their Interpretation. author.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905-01-01). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ "The Suwannee River, Exploring Florida: A Social Studies Resource for Students and Teachers". College of Education, University of South Florida. 2002. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ↑ Bright, William (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 466–467. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ↑ Martin, Jack B.; Mauldin, Margaret McKane (2004-12-01). A Dictionary of Creek/Muskogee. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803283024.

- ↑ Worth vol. I, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Milanich, Jerald T. (1996-08-14). Timucua. VNR AG. ISBN 9781557864888.

- ↑ http://www.jacksonville.com/tu-online/stories/030707/met_8429196.shtml/

- ↑ "Summary of Bills Related to Arts, Cultural, Arts Education. Or Historical Resources That Passed the 2008 Florida Legislature May 5, 2008", Retrieved on 2011-12-14 from http://www.flca.net/images/50508_Status_of_Bills.pdf.

- ↑ Center for American Music. "Old Folks at Home". Center for American Music Library. Archived from the original on 2009-01-11. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

References

- Milanich, Jerald T. (2006). Laboring in the Fields of the Lord: Spanish Missions and Southeastern Indians. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2966-X

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucua Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida. Volume 1: Assimilation. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1574-X. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- "Florida Dept. of Transportation, Florida Bridge Information" (PDF).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suwannee River. |

- Suwannee Online

- USF page with history

- EPA info on Suwannee basin

- Suwannee River Wilderness Trail

- Info on the Suwannee River and surrounding areas from SRWMD

- Suwanee River Watershed - Florida DEP

- Recording of "Old Folks at Home" at the 1955 Florida Folk Festival; made available for public use by the State Archives of Florida

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Suwannee River

- Where it's SpringTime year round <http://www.springsrus.com>

Further reading

- Light, H.M., et al. (2002). Hydrology, vegetation, and soils of riverine and tidal floodplain forests of the lower Suwannee River, Florida, and potential impacts of flow reductions [U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1656A]. Denver: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.