Subdural hematoma

| Subdural hematoma | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Subdural haematoma, subdural haemorrhage |

|

| |

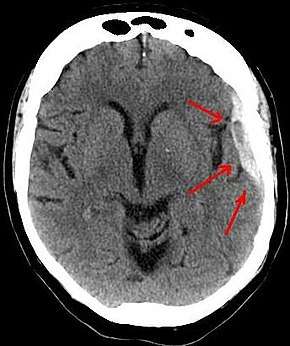

| Subdural hematoma as marked by the arrow with significant midline shift | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery |

A subdural hematoma (SDH), is a type of hematoma, usually associated with traumatic brain injury. Blood gathers between the inner layer of the dura mater and the arachnoid mater. Usually resulting from tears in bridging veins which cross the subdural space, subdural hemorrhages may cause an increase in intracranial pressure (ICP), which can cause compression of and damage to delicate brain tissue. Subdural hematomas are often life-threatening when acute. Chronic subdural hematomas, however, have a better prognosis if properly managed.

In contrast, epidural hematomas are usually caused by tears in arteries, resulting in a build-up of blood between the dura mater and skull. Subarachnoid hemorrhage, the third type of brain hemorrhages, is bleeding into the subarachnoid space — the area between the arachnoid membrane and the pia mater surrounding the brain.

Classification

Subdural hematomas are divided into acute, subacute, and chronic, depending on the speed of their onset.[1] Acute subdural hematomas that are due to trauma are the most lethal of all head injuries and have a high mortality rate if they are not rapidly treated with surgical decompression.[2]

Acute bleeds often develop after high speed acceleration or deceleration injuries and are increasingly severe with larger hematomas. They are most severe if associated with cerebral contusions.[3] Though much faster than chronic subdural bleeds, acute subdural bleeding is usually venous and therefore slower than the typically arterial bleeding of an epidural hemorrhage. Acute subdural bleeds have a high mortality rate, higher even than epidural hematomas and diffuse brain injuries, because the force (acceleration/deceleration) required to cause them causes other severe injuries as well.[4] The mortality rate associated with acute subdural hematoma is around 60 to 80%.[5]

Chronic subdural bleeds develop over a period of days to weeks, often after minor head trauma, though such a cause is not identifiable in 50% of patients.[6] They may not be discovered until they present clinically months or years after a head injury.[7] The bleeding from a chronic bleed is slow, probably from repeated minor bleeds, and usually stops by itself.[8][9] Since these bleeds progress slowly, they present the chance of being stopped before they cause significant damage. Small chronic subdural hematomas, those less than a centimeter wide, have much better outcomes than acute subdural bleeds: in one study, only 22% of patients with chronic subdural bleeds had outcomes worse than "good" or "complete recovery".[3] Chronic subdural hematomas are common in the elderly.[7]

Signs and symptoms

| Hematoma type | Epidural | Subdural |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Between the skull and the outer endosteal layer of the dura mater | Between dura mater and arachnoid mater.[10] |

| Involved vessel | Temperoparietal locus (most likely) - Middle meningeal artery Frontal locus - anterior ethmoidal artery Occipital locus - transverse or sigmoid sinuses Vertex locus - superior sagittal sinus | Bridging veins |

| Symptoms (depend on severity)[11] | Lucid interval followed by unconsciousness | Gradually increasing headache and confusion |

| CT appearance | Biconvex lens | Crescent-shaped |

Symptoms of subdural hemorrhage have a slower onset than those of epidural hemorrhages because the lower pressure veins bleed more slowly than arteries. Therefore, signs and symptoms may show up in minutes, if not immediately[12] but can be delayed as much as 2 weeks.[13] If the bleeds are large enough to put pressure on the brain, signs of increased ICP (intracranial pressure) or damage to part of the brain will be present.[3]

Other signs and symptoms of subdural hematoma can include any combination of the following:

- A history of recent head injury

- Loss of consciousness or fluctuating levels of consciousness

- Irritability

- Seizures

- Pain

- Numbness

- Headache (either constant or fluctuating)

- Dizziness

- Disorientation

- Amnesia

- Weakness or lethargy

- Nausea or vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Personality changes

- Inability to speak or slurred speech

- Ataxia, or difficulty walking

- Loss of muscle control

- Altered breathing patterns

- Hearing loss or hearing ringing (tinnitus)

- Blurred Vision

- Deviated gaze, or abnormal movement of the eyes.[3]

Causes

Subdural hematomas are most often caused by head injury, when rapidly changing velocities within the skull may stretch and tear small bridging veins. Subdural hematomas due to head injury are described as traumatic. Much more common than epidural hemorrhages, subdural hemorrhages generally result from shearing injuries due to various rotational or linear forces.[3][8] Subdural hemorrhage may be seen in shaken baby syndrome, in which similar shearing forces may cause retinal hemorrhages. Subdural hematoma is also commonly seen in the elderly and in alcoholics, who have evidence of cerebral atrophy. Cerebral atrophy increases the length the bridging veins have to traverse between the two meningeal layers, hence increasing the likelihood of shearing forces causing a tear. It is also more common in patients on anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs, such as warfarin and aspirin. Patients on these medications can have a subdural hematoma after a relatively minor traumatic event. A further cause can be a reduction in cerebral spinal fluid pressure which can create a low pressure in the subarachnoid space, pulling the arachnoid away from the dura mater and leading to a rupture of the blood vessels.

Risk factors

Factors increasing the risk of a subdural hematoma include very young or very old age. As the brain shrinks with age, the subdural space enlarges and the veins that traverse the space must travel over a wider distance, making them more vulnerable to tears. This and the fact that the elderly have more brittle veins make chronic subdural bleeds more common in older patients.[6] Infants, too, have larger subdural spaces and are more predisposed to subdural bleeds than are young adults.[3] For this reason, subdural hematoma is a common finding in shaken baby syndrome. In juveniles, an arachnoid cyst is a risk factor for a subdural hematoma.[14]

Other risk factors for subdural bleeds include taking blood thinners (anticoagulants), long-term alcohol abuse, dementia, and the presence of a cerebrospinal fluid leak.[15]

Pathophysiology

Acute subdural haematoma is usually caused external trauma that creates tension in the wall of a bridging vein as it passes between the arachnoid and dural layers, i.e. the subdural space, of the brain's lining. This is because in the short course of the vein in the subdural space, circumferential arrangement of collagen surrounding the vein causes it to be susceptible to tear by this tension. However, intracerebral hemorrhage and rupture of cortical vessels (vessels running on the surface of the brain) can also cause subdural haematoma. Such haematoma usually accumulates in between the two layers of the dura membrane. Such haematoma can cause ischemic brain damage by two mechanisms: pressure effect on the cortical blood vessels,[16] and vasoconstriction due to the substances may be released from the collected material in a subdural hematoma, causing further ischemia under the site by restricting blood flow to the brain.[9] When the brain is denied adequate blood flow, a biochemical cascade known as the ischemic cascade is unleashed, and may ultimately lead to brain cell death.[17] This condition lead to higher risk of death for the patient.[16]

Subdural haematoma may continually grow in size by the pressure effect of the haematoma on the brain. This causes the intracranial pressure of the brain to rise, squeezing the intracranial blood into the dural venous sinuses, raising the dural venous pressure, and resulting in more bleeding from the ruptured bridging veins. Subdural haematoma only stopped to enlarge when the pressure of the haematoma equalises with the intracranial pressure of the brain, as the space for haematoma expansion getting smaller and smaller.[16]

Chronic subdural haematoma is usually asymptomatic until four to seven weeks later. In this case, accumulation of blood in the dural space is caused by inflammation. Trauma causes damage to the dural border cells (e.g. separation of dura membrane bilayer), resulting in inflammatory reaction.[18] Post craniotomy for unruptured intracranial aneurysm is another risk factor for the development of chronic subdural haematoma. The incision of arachnoid membrane during the operation causes leakage of CSF into the subdural space, leading to inflammation. This post-operative complication would usually resolved spontaneously.[19] Inflammation causes the new membrane formation through fibrosis. The inflammatory process also produces new fragile and leaky blood vessels through angiogenesis, permitting the leakage of red blood cells, white blood cells, and plasma into the haematoma cavity and easily causes mirco bleeds. Besides, tearing of arachnoid mater during trauma causes leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) into the haematoma cavity, causing increase in haematoma size over time. Excessive fibrinolysis is another factor that causes continuous bleeding. Examples of pro-inflammatory mediators acted in the haematoma expansion process are: Interleukin 1α (IL1A), Interleukin 6, Interleukin 8; while the anti-inflammatory mediator is Interleukin 10. Mediators that promote angiogenesis are: angiopoietin and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Meanwhile, prostaglandin E2 promotes the expression of VEGF. Matrix metalloproteinases remove surrounding collagen, thus providing space for new blood vessels to grow.[18]

Diagnosis

It is important that a person receive medical assessment, including a complete neurological examination, after any head trauma. A CT scan or MRI scan will usually detect significant subdural hematomas.

Subdural hematomas occur most often around the tops and sides of the frontal and parietal lobes.[3][8] They also occur in the posterior cranial fossa, and near the falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli.[3] Unlike epidural hematomas, which cannot expand past the sutures of the skull, subdural hematomas can expand along the inside of the skull, creating a concave shape that follows the curve of the brain, stopping only at the dural reflections like the tentorium cerebelli and falx cerebri.

On a CT scan, subdural hematomas are classically crescent-shaped, with a concave surface away from the skull. However, they can have a convex appearance, especially in the early stage of bleeding. This may cause difficulty in distinguishing between subdural and epidural hemorrhages. A more reliable indicator of subdural hemorrhage is its involvement of a larger portion of the cerebral hemisphere since it can cross suture lines, unlike an epidural hemorrhage. Subdural blood can also be seen as a layering density along the tentorium cerebelli. This can be a chronic, stable process, since the feeding system is low-pressure. In such cases, subtle signs of bleeding such as effacement of sulci or medial displacement of the junction between gray matter and white matter may be apparent.

| Age | Attenuation (HU) |

|---|---|

| First hours | +75 to +100[20] |

| After 3 days | +65 to +85[20] |

| After 10-14 days | +35 to +40[21] |

Fresh subdural bleeding is hyperdense, but becomes more hypodense over time due to dissolution of cellular elements. After somewhere between 3–14 days, the bleeding becomes isodense with brain tissue and may therefore be missed.[22] Subsequently, it will become more hypodense than brain tissue.

Treatment

Treatment of a subdural hematoma depends on its size and rate of growth. Some small subdural hematomas can be managed by careful monitoring as the clot is eventually resorbed naturally. Other small subdural hematomas can be managed by inserting a temporary small catheter through a hole drilled through the skull and sucking out the hematoma; this procedure can be done at the bedside. Large or symptomatic hematomas require a craniotomy, the surgical opening of the skull. A surgeon then opens the dura, removes the blood clot with suction or irrigation, and identifies and controls sites of bleeding.[23][24] Postoperative complications include increased intracranial pressure, brain edema, new or recurrent bleeding, infection, and seizure. The injured vessels must be repaired.

Depending on the size and deterioration, age of the patient, and anaesthetic risk posed, subdural hematomas occasionally require craniotomy for evacuation; most frequently, simple burr holes for drainage; often conservative treatment; and rarely, palliative treatment in patients of extreme age or with no chance of recovery.[25]

In those with a chronic subdural hematoma, but without a history of seizures, the evidence is unclear if using anticonvulsants is harmful or beneficial.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ Subdural Hematoma Surgery at eMedicine

- ↑ "Acute Subdural Hematomas". UCLA Health. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Imaging in Subdural Hematoma at eMedicine

- ↑ Penetrating Head Trauma at eMedicine

- ↑ Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) - Definition, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology at eMedicine

- 1 2 Downie A. 2001. "Tutorial: CT in head trauma" Archived 2005-11-06 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved on August 7, 2007.

- 1 2 Kushner D (1998). "Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Toward Understanding Manifestations and Treatment". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (15): 1617–1624. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.15.1617. PMID 9701095.

- 1 2 3 University of Vermont College of Medicine. "Neuropathology: Trauma to the CNS." Accessed through web archive on August 8, 2007.

- 1 2 Graham DI and Gennareli TA. Chapter 5, "Pathology of brain damage after head injury" Cooper P and Golfinos G. 2000. Head Injury, 4th Ed. Morgan Hill, New York.

- ↑ "Subdural Haematoma". Patient. Patient Platform Ltd. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ Gillet, Jane. "What's the Difference Between a Subdural and Epidural Hematoma?" (PDF). brainline.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Subdural hematoma : MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". Nlm.nih.gov. 2012-06-28. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- ↑ Sanders MJ and McKenna K. 2001. Mosby’s Paramedic Textbook, 2nd revised Ed. Chapter 22, "Head and facial trauma." Mosby.

- ↑ Mori K, Yamamoto T, Horinaka N, Maeda M (2002). "Arachnoid cyst is a risk factor for chronic subdural hematoma in juveniles: twelve cases of chronic subdural hematoma associated with arachnoid cyst". J. Neurotrauma. 19 (9): 1017–27. doi:10.1089/089771502760341938. PMID 12482115.

- ↑ Beck J; Gralla J; Fung C; Ulrich C; Schuct P; Fichtner J; ... Raabe A (December 2014). "Spinal cerebrospinal fluid leak as the cause of chronic subdural hematomas in nongeriatric patients". Journal of Neurosurgery. 121 (6): 1380–1387. doi:10.3171/2014.6.JNS14550. PMID 25036203.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Jimmy D; Nader, Remi (June 2014). "Acute subdural hematoma from bridging vein rupture: a potential mechanism for growth". Journal of Neurosurgery. 120 (6): 1378–1384. doi:10.3171/2013.10.JNS13272. PMID 24313607.

- ↑ Tandon, PN (2001). "Acute subdural haematoma : a reappraisal". Neurology India. 49 (1): 3–10. PMID 11303234. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

. The possibility of direct effect of some vasoactive substances released by the blood clot, being responsible for the ischaemia, seems attractive.

- 1 2 Edlmann, Ellie; Giorgi-Coll, Susan; Whitfield, Peter C. (30 May 2017). "Pathophysiology of chronic subdural haematoma: inflammation, angiogenesis and implications for pharmacotherapy". Journal if Neuroinflammation. 14 (1): 108. doi:10.1186/s12974-017-0881-y. PMC 5450087. PMID 28558815.

- ↑ Tanaka, Y; Ohno, K (1 June 2013). "Chronic subdural hematoma - an up-to-date concept" (PDF). Journal of Medical and Dental Sciences. 60 (2): 55–61. PMID 23918031. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- 1 2 Fig 3 in: Rao, Murali Gundu (2016). "Dating of Early Subdural Haematoma: A Correlative Clinico-Radiological Study". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 10 (4): HC01–5. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/17207.7644. ISSN 2249-782X. PMC 4866129. PMID 27190831.

- ↑ Dr Rohit Sharma and A.Prof Frank Gaillard. "Subdural haemorrhage". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ↑ "Intracranial Hemorrhage - Subdural Hematomas (SDH)". Loyola University Chicago. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ↑ Koivisto T, Jääskeläinen JE (2009). "Chronic subdural haematoma–to drain or not to drain?". Lancet. 374 (9695): 1040&ndash, 1041. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61682-2. PMID 19782854.

- ↑ Santarius T, Kirkpatrick PJ, Dharmendra G, et al. (2009). "Use of drains versus no drains after burr-hole evacuation of chronic subdural haematoma: a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 374 (9695): 1067&ndash, 1073. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61115-6. PMID 19782872.

- ↑ de Araújo Silva, DaniloOtávio; Matis, GeorgiosK; Kitamura, MatheusAugusto Pinto; de Carvalho Junior, EduardoVieira; Silva, Monalisade Moura; Pereira, CarlosUmberto; da Silva, JoacilCarlos; de Azevedo Filho, HildoRocha Cirne; Costa, LeonardoFerraz; Barbosa, Breno JoséA. P.; Birbilis, TheodossiosA (2012). "Chronic subdural hematomas and the elderly: Surgical results from a series of 125 cases: Old "horses" are not to be shot!". Surgical Neurology International. 3 (1): 150. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.104744. ISSN 2152-7806. PMC 3551521. PMID 23372967.

- ↑ Ratilal, BO; Pappamikail, L; Costa, J; Sampaio, C (Jun 6, 2013). "Anticonvulsants for preventing seizures in patients with chronic subdural haematoma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD004893. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004893.pub3. PMID 23744552.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Subdural hematoma. |