Viaduct

The 1812 Laigh Milton Viaduct in Ayrshire – the oldest surviving railway bridge in Scotland | |

| Ancestor | Trestle bridge, Box girder bridge |

|---|---|

| Related | None |

| Descendant | None |

| Carries | Expressways, highways, streets, railways |

| Span range | Short (multiple) |

| Material | reinforced concrete, prestressed concrete, masonry |

| Movable | No |

| Design effort | medium |

| Falsework required | available for use, since viaducts are all composed of low bridges. |

A viaduct is a bridge composed of several small spans for crossing a valley, dry or wetland, or forming an overpass or flyover.[1][2][3][4][5]

The term is conventional for a rail flyover as opposed to a flying junction or a rail bridge which crosses one feature.

The term viaduct is derived from the Latin via for road and ducere, to lead. The ancient Romans did not use the term; it is a nineteenth-century derivation from an analogy with aqueduct.[4]

Like the Roman aqueducts, many early viaducts comprised a series of arches of roughly equal length.

Over land

The longest in antiquity may have been the Pont Serme which crossed wide marshes in southern France.[6] At it's longest point, it measured 2,679 meters with a width of 22 meters.

Viaducts are commonly used in many cities that are railroad centers, such as Chicago, Atlanta, Birmingham, London and Manchester. These viaducts cross the large railroad yards that are needed for freight trains there, and also cross the multi-track railroad lines that are needed for heavy railroad traffic. These viaducts keep highway and city street traffic from having to be continually interrupted by the train traffic. Likewise, some viaducts carry railroads over large valleys, or they carry railroads over cities with many cross-streets and avenues.

Many viaducts over land connect points of similar height in a landscape, usually by bridging a river valley or other eroded opening in an otherwise flat area. Often such valleys had roads descending either side (with a small bridge over the river, where necessary) that become inadequate for the traffic load, necessitating a viaduct for "through" traffic.[7] Such bridges also lend themselves for use by rail traffic, which requires straighter and flatter routes.[8] Some viaducts have more than one deck, such that one deck has vehicular traffic and another deck carries rail traffic. One example of this is the Prince Edward Viaduct in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, that carries motor traffic on the top deck as Bloor Street, and metro as the Bloor-Danforth subway line on the lower deck, over the steep Don River valley. Others were built to span settled areas, crossing over roads beneath—the reason for many viaducts in London.

Over water

Viaducts over water make use of islands or successive arches. They are often combined with other types of bridges or tunnels to cross navigable waters as viaduct sections, while less expensive to design and build than tunnels or bridges with larger spans, typically lack sufficient horizontal and vertical clearance for large ships. See the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.

The Millau Viaduct is a cable-stayed road-bridge that spans the valley of the river Tarn near Millau in southern France. Designed by the French bridge engineer Michel Virlogeux, in collaboration with architect Norman Robert Foster, it is the tallest vehicular bridge in the world, with one pier's summit at 343 metres (1,125 ft)—slightly taller than the Eiffel Tower and only 38 m (125 ft) shorter than the Empire State Building. It was formally dedicated on 14 December 2004 and opened to traffic two days later. The viaduct Danyang–Kunshan Grand Bridge in China is the longest bridge in the world according to Guinness World Records as of 2011.[9]

Land use below viaducts

Where a viaduct is built across land rather than water, the space below the arches may be used for businesses such as car parking, vehicle repairs, light industry, bars and nightclubs. In the United Kingdom, many railway lines in urban areas have been constructed on viaducts, and so the infrastructure owner Network Rail has an extensive property portfolio in arches under viaducts.[10] In Berlin the space under the arches of elevated subway lines is used for several different purposes, including small eateries or bars.

A notable exception to this trend is in the U.S. City of Chicago (pop 2.7 million 2018), where parking regulations forbid parking in a viaduct/underpass. This is worth noting for anybody traveling to Chicago, since the law is irregular and generally there is no signage or notice of the rule.

Past and future

Elevated expressways were built in major cities such as Boston (Central Artery), Seoul, Tokyo, Toronto (Gardiner Expressway).[11] Some were demolished because they were unappealing and divided the city. However, in developing nations such as Thailand, India (Delhi-Gurgaon Expressway), China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nicaragua elevated expressways have been built and more are under construction to improve traffic flow, particularly as a workaround of land shortage when built atop surface roads. In Indonesia viaducts are used for railways in Java and also for highways such as the Jakarta Inner Ring Road. The Coulée verte René-Dumont in Paris, France is a disused viaduct which was converted to an urban park in 1993.

Gallery

- Renmin Lu Viaduct of the city of Guangzhou (formerly Canton) is the first viaduct built in mainland China.

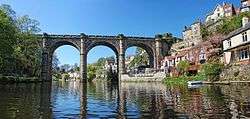

Knaresborough viaduct is an elegant four-span bridge standing 78 ft high above the River Nidd.

Knaresborough viaduct is an elegant four-span bridge standing 78 ft high above the River Nidd. A 21-arch bridge spanning Yorkshire's Wharfe valley, engineered for the Leeds and Thirsk Railway circa 1850.

A 21-arch bridge spanning Yorkshire's Wharfe valley, engineered for the Leeds and Thirsk Railway circa 1850. A derelict viaduct known as Lobb Ghyll, built by the Midland Railway in 1888 to connect Ilkley and Skipton.

A derelict viaduct known as Lobb Ghyll, built by the Midland Railway in 1888 to connect Ilkley and Skipton. The Prince Edward Viaduct in Toronto is an example of a viaduct with multiple decks.

The Prince Edward Viaduct in Toronto is an example of a viaduct with multiple decks. Railway viaduct crossing the Santa Ana River in Riverside, California, United States. Built in 1903.

Railway viaduct crossing the Santa Ana River in Riverside, California, United States. Built in 1903. The Cypress Street Viaduct was an example of a double decker freeway in Oakland, California which collapsed in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and was later demolished.

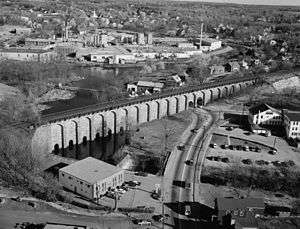

The Cypress Street Viaduct was an example of a double decker freeway in Oakland, California which collapsed in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and was later demolished.- The Tunkhannock Viaduct in Nicholson, Pennsylvania is thought to be the largest concrete bridge in the world.

The Alaskan Way Viaduct in Seattle, Washington, United States. Demolition is scheduled to start in early 2019, (or possibly later) after the tunnel being built to replace it is complete.

The Alaskan Way Viaduct in Seattle, Washington, United States. Demolition is scheduled to start in early 2019, (or possibly later) after the tunnel being built to replace it is complete. The Millau Viaduct, and the town of Millau, France on the right. It is the tallest bridge in the world.

The Millau Viaduct, and the town of Millau, France on the right. It is the tallest bridge in the world. The Garabit Viaduct is a steel truss arch bridge.

The Garabit Viaduct is a steel truss arch bridge. The Lewis and Clark Viaduct connects Downtown Kansas City, Missouri with downtown Kansas City, Kansas.

The Lewis and Clark Viaduct connects Downtown Kansas City, Missouri with downtown Kansas City, Kansas. Crumlin Viaduct, on the Taff Vale Extension of the West Midland Railway, 1855.

Crumlin Viaduct, on the Taff Vale Extension of the West Midland Railway, 1855.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Viaduct. |

| Look up viaduct in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- ↑ "Definition of VIADUCT". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "dict.org- Viaduct". www.dict.org. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "dict.org- Viaduct". www.dict.org. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- 1 2 "viaduct - Definition of viaduct in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "the definition of viaduct". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Colin O’Connor: Roman Bridges, Cambridge University Press 1993, ISBN 0-521-39326-4, p. 99

- ↑ Brownlee, Christy (March 2005) "Taking the high road: France's new bridge helps a small town dodge traffic—and set a new world record" SuperScience 16(6): pp.12–15;

- ↑ Davidsen, Judith (April 1993) "A new "lite" rail viaduct formula: Norman Foster designs a rapid-transit viaduct for Rennes, France" Architectural Record 181(4): p.26;

- ↑ Longest bridge, Guinness World Records. Last accessed July 2011.

- ↑ http://property.networkrail.co.uk/industrialunitstolet.aspx

- ↑ "Toronto built, then demolished an expressway" (PDF). tac-atc.ca. Retrieved 27 March 2018.