First Punic War

| First Punic War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Punic Wars | |||||||||

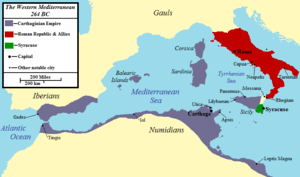

Western Mediterranean Sea in 264 BC. Rome is shown in red, Carthage in purple, and Syracuse in green. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Roman Republic |

Carthage Syracuse | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Marcus Atilius Regulus (POW) Gaius Lutatius Catulus Gaius Duilius |

Hamilcar Barca Hanno the Great Hasdrubal the Fair Xanthippus | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

700 quinqueremes 400,000 dead, including 50,000 Roman citizens | 500 quinqueremes, 350,000 dead | ||||||||

The First Punic War (264 to 241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Ancient Carthage and the Roman Republic, the two great powers of the Western Mediterranean. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and greatest naval war of antiquity, the two powers struggled for supremacy, primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters, and also in North Africa.

The war began in 264 BC with the Roman conquest of the Carthaginian-controlled city of Messina in Sicily, granting Rome a military foothold on the island. The Romans built up a navy to challenge Carthage, the greatest naval power in the Mediterranean, for control over the waters around Sicily. In naval battles and storms, 700 Roman and 500 Carthaginian quinqueremes were lost, along with hundreds of thousands of lives. Command of the sea was won and lost by both sides repeatedly. A Roman invasion of Carthaginian Africa was destroyed in battle and the Roman consul Marcus Atilius Regulus was captured by the Carthaginians in 255. In 23 years, the Romans slowly conquered Sicily and drove the Carthaginians to the west end of the island.

After both sides had been brought to a state of near exhaustion, the Romans mobilized their citizenry's private wealth and created a new fleet under consul Gaius Lutatius Catulus. The Carthaginian fleet was destroyed at the Aegates Islands in 241, forcing the cut-off Carthaginian troops on Sicily to give up. A peace treaty was signed in which Carthage was made to pay a heavy indemnity and Rome ejected Carthage from Sicily, annexing the island as a Roman province.

The war was followed by a failed revolt against the Carthaginian Empire. The Romans exploited Carthage's weakness to seize the Carthaginian possessions of Sardinia and Corsica in violation of the peace treaty. The unresolved strategic competition between Rome and Carthage would lead to the eruption of the Second Punic War in 218 BC.

Name

The series of wars between Rome and Carthage took the name "Punic" from the Latin adjective for Carthaginian, Punicus. This is derived from Poeni (Carthaginians) and refers to the Carthaginian heritage as Phoenician colonists.[1] A Carthaginian name(s) for the conflicts does not survive in any records.

Background

Rome

Rome had recently emerged as the leading city-state in the Italian Peninsula, a wealthy, powerful, expansionist republic with a successful citizen army.[2] Over the past one hundred years, Rome had come into conflict, and defeated rivals on the Italian peninsula, then incorporated them into the Roman political world. First, the Latin League was forcibly dissolved during the Latin War,[3] then the power of the Samnites was broken during the three prolonged Samnite wars,[4] and then the Greek cities of Magna Graecia (southern Italy) submitted to Roman power at the conclusion of the Pyrrhic War.[4] By the beginning of the First Punic War, the Romans had secured the whole of the Italian peninsula, except Gallia Cisalpina in the Po Valley.

Carthage

Carthage was a republic that dominated the political, military and economic affairs of the western Mediterranean Sea, especially on the North African coasts and islands, and above all, due to its navy.[2][5] It originated as a Phoenician colony in Africa, near modern Tunis. Carthage had become a wealthy centre for trade networks extending from Gadir (Cádiz) along the coasts of southern Iberia and North Africa, across the Balearic Islands, Corsica, Sardinia, and the western half of Sicily, to the ports of the eastern Mediterranean, including Tyre, its mother city, on the shores of the Levant.[6] At the height of power, just before the First Punic War, Carthage was hostile to foreign ships (such as Roman and Greek vessels) in the western Mediterranean.[7]

North African peoples

North African peoples, such as the Berbers, in the area around Carthage were loosely associated with Carthage.[8] In the midst of the First Punic War, some tribes rebelled against Carthage, opening a second front while the Carthaginians battled the Romans in Sicily.

Greek colonists

Greek colonists were also a major presence in the western Mediterranean, following centuries of colonial settlement, trade and conflicts with Rome over Magna Graecia and with Carthage over places such as Sicily.[9][10] The rich, strategically influential, and well-fortified Greek colony of Syracuse was politically independent of Rome and Carthage. Hostilities of the First Punic War began with developments involving the Romans, Carthaginians, and Greek colonists in Sicily and southern Italy.

Beginning

In 288 BC, the Mamertines, a group of Italian (Campanian) mercenaries originally hired by Agathocles of Syracuse, occupied the city of Messana (modern Messina) in the north-eastern tip of Sicily, killing all the men and taking the women as their wives.[11] At the same time, a group of Roman troops made up of Campanian "citizens without the vote" revolted and seized control of Rhegium, lying across the Straits of Messina on the mainland of Italy. In 270 BC, the Romans regained control of Rhegium and severely punished the survivors of the revolt. In Sicily, the Mamertines ravaged the countryside and collided with the expanding regional empire of the independent city of Syracuse. Hiero II, tyrant of Syracuse, defeated the Mamertines near Mylae on the Longanus River.[12] Following their defeat, the Mamertines appealed to both Rome and Carthage for assistance. The Carthaginians acted first, approached Hiero to take no further action and convinced the Mamertines to accept a Carthaginian garrison in Messana. Either unhappy with the prospect of a Carthaginian garrison or convinced that the recent alliance between Rome and Carthage against Pyrrhus reflected cordial relations between the two, the Mamertines, hoping for more reliable protection, petitioned Rome for an alliance. However, the rivalry between Rome and Carthage had grown since the war with Pyrrhus and that alliance was simply no longer feasible.[13]

According to the historian Polybius, considerable debate took place in Rome on the question as to whether to accept the Mamertines' appeal for help and thus likely enter into a war with Carthage. The Romans did not wish to come to the aid of soldiers who had unjustly stolen a city from its rightful possessors, and they were still recovering from the insurrection of Campanian troops at the Battle of Rhegium in 271 BC. However, many were also unwilling to see Carthaginian power in Sicily expand even further. Leaving them at Messana would give the Carthaginians a free hand to deal with Syracuse. After the Syracusans had been defeated, the Carthaginian takeover of Sicily would essentially be complete.[14] A deadlocked senate put the matter before the popular assembly, where it was decided to accept the Mamertines' request and Appius Claudius Caudex was appointed commander of a military expedition with orders to cross to Messana.[15][16]

Roman landing and advance to Syracuse

Sicily is a hilly volcanic island, with geographical obstacles and rough terrain making lines of communication difficult to maintain. For this reason, land warfare played a secondary role in the First Punic War. Land operations were confined to small scale raids and skirmishes, with few pitched battles. Sieges and land blockades were the most common large-scale operations for the regular army. The main blockade targets were the important ports since neither Carthage nor Rome were based in Sicily, and both needed continuous reinforcements and communication with their mainlands.[17]

The land war in Sicily began with the Roman landing at Messana in 264 BC. According to Polybius, despite the Carthaginian pre-war naval advantage, the Roman landing was virtually unopposed. Two legions commanded by Appius Claudius Caudex disembarked at Messana, where the Mamertines had expelled the Carthaginian garrison commanded by Hanno (no relation to Hanno the Great).[18] After defeating the Syracusan and Carthaginian forces besieging Messana, the Romans marched south and in turn besieged Syracuse.[19] After a brief siege, with no Carthaginian help in sight, Syracuse made peace with the Romans.[20]

According to the terms of the treaty, Syracuse would become a Roman ally, pay a somewhat light indemnity of 100 talents of silver to Rome and, perhaps most importantly, agree to help supply the Roman army in Sicily.[20] That solved the Roman problem of having to keep an overseas army provisioned while facing an enemy with a superior navy.[20][21] Following the defection of Syracuse from Carthage, several other smaller Carthaginian dependencies in Sicily also switched to the Roman side.[20]

Carthage prepares for war

Meanwhile, Carthage had begun to build a mercenary army in Africa, which was to be shipped to Sicily to meet the Romans. According to the historian Philinus, this army was composed of 50,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 60 elephants and partly composed of Ligurians, Celts and Iberians.[22][23]

In past wars on the island of Sicily, Carthage had won by relying on certain fortified strong-points throughout the island, and their plan was to conduct the land war in the same fashion. The mercenary army would operate in the open against the Romans, while the strongly fortified cities would provide a defensive base from which to operate.[20]

Battle of Agrigentum

In 262 BC, Rome besieged Agrigentum, an operation that involved both consular armies—a total of four Roman legions—and took several months to resolve. The garrison of Agrigentum (known to the Greeks as Acragas) managed to call for reinforcements and the Carthaginian relief force, commanded by Hanno, destroyed the Roman supply base at Erbessus.[24] With supplies from Syracuse cut, the Romans were now besieged and constructed a line of contravallation.[24] After a few skirmishes, disease struck the Roman army while supplies in Agrigentum were running low, and both sides saw an open battle as preferable to the current situation.[24] Although the Romans won a clear victory over the Carthaginian relief force at the Battle of Agrigentum, the Carthaginian army defending the city managed to escape.[24] Agrigentum, now lacking any real defences, fell easily to the Romans, who then sacked the city and enslaved the populace.[24][25]

Rome builds a fleet

At the beginning of the First Punic War, Rome had virtually no experience in naval warfare, whereas the strong and powerful Carthage had a great deal of experience on the seas thanks to its centuries of sea-based trade. Nevertheless, the growing Roman Republic soon understood the importance of Mediterranean control in the outcome of the conflict.[26]

Origin of Roman design

The first major Roman fleet was constructed after the victory of Agrigentum in 261 BC. Some historians have speculated that, since Rome lacked advanced naval technology, the design of the warships was probably copied from captured Carthaginian triremes and quinqueremes or from ships that had beached on Roman shores due to storms.[27] According to Polybius, the Romans seized a shipwrecked Carthaginian quinquereme, and used it as a blueprint for their own ships.[28] Other historians have pointed out that Rome did have experience with naval technology, as she patrolled her coasts against piracy.[29] Another possibility is that Rome received technical assistance from its seafaring Sicilian ally, Syracuse.[29] Regardless of the state of their naval technology at the start of the war, Rome quickly adapted.[30]

The corvus

In order to compensate for the lack of experience, and to make use of standard land military tactics at sea,[31] the Romans equipped their new ships with a special boarding device, the corvus.[32] The Roman military was a land-based army, while Carthage was primarily a naval power. This boarding-bridge allowed the Roman navy to circumvent some of Carthage's naval skills by using their marines to board Carthaginian ships and fight in hand-to-hand combat. Instead of manoeuvring to ram, which was the standard naval tactic at the time, corvus equipped ships would manoeuver alongside the enemy vessel, deploy the bridge which would attach to the enemy ship through spikes on the end of the bridge, and send legionaries across as boarding parties.[33][34]

The new weapon would prove its worth in the Battle of Mylae, the first Roman naval victory, and would continue to do so in the following years, especially in the huge Battle of Cape Ecnomus. The addition of the corvus forced Carthage to review its military tactics, and since the city had difficulty in doing so, Rome had the naval advantage.[35]

Battle of Mylae

The Roman fleet, under the command of Gaius Duilius, engaged the Carthaginians, under general Hannibal Gisco, off northern Mylae in 260 BC. Polybius states that the Carthaginians had 130 ships, but does not give an exact figure for the Romans.[36] The loss of 17 ships at the Lipari Islands from a starting total of 120 ships suggests that Rome had 103 remaining. However, it is possible that this number was greater, thanks to captured ships and the assistance of Roman allies.[37] The Carthaginians anticipated victory, due to their superior experience at sea.[36]

The corvi were very successful, and helped the Romans seize the first 30 Carthaginian ships that were close enough. In order to avoid the corvi, the Carthaginians were forced to navigate around them and approach the Romans from behind, or from the side. The corvus was usually still able to pivot and grapple most oncoming ships.[38] After a further 20 Carthaginian ships had been hooked and lost to the Romans, Hannibal Gisco retreated with his surviving ships, leaving Duilius with a clear victory.

Instead of pursuing the remaining Carthaginians, Duilius sailed to Sicily to relieve the city of Segesta, which had been under siege from the Carthaginian infantry commander Hamilcar.[39] Modern historians have wondered at Duilius’ decision not to immediately follow up with another naval attack, but Hannibal Gisco’s remaining 80 ships were probably still too strong for Rome to conquer.[40]

Hamilcar's counter-attack

The Roman advance now continued westward from Agrigentum to relieve the besieged city of Macella in 260 BC,[41] which had sided with Rome and was attacked by the Carthaginians for doing so. In the north, the Romans, with their northern sea flank secured by their naval victory at the Battle of Mylae, advanced toward Thermae. They were defeated there by the Carthaginians under Hamilcar (a popular Carthaginian name, not to be confused with Hannibal Barca's father, with the same name) in 260 BC.[42] The Carthaginians took advantage of this victory by counter-attacking, in 259 BC, and seizing Enna. Hamilcar continued south to Camarina, in Syracusan territory, presumably with the intent to convince the Syracusans to rejoin the Carthaginian side.[43]

Battles in Sardinia and Corsica

In 259 BC, consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio occupied Aleria in Corsica and probably Olbia in Sardinia. Hanno died while fighting at Olbia. The Romans withdrew because of the arrival of a Carthaginian fleet. Cornelius Scipio celebrated his victories over the Carthaginians and Sardinians with a triumph the following year[44]. During the same year, a naval battle occurred near Sulci. The Carthaginian fleet was defeated and the commander Hannibal Gisco, who abandoned his men and fled to Sulci, was later captured by his soldiers and crucified.

Continued Roman advance

The next year, 258 BC, the Romans were able to regain the initiative by retaking Enna and Camarina. In central Sicily, they took the town of Mytistraton, which they had attacked twice previously. The Romans also moved in the north by marching across the northern coast toward Panormus, but were not able to take the city.[45]

Invasion of Africa

After their conquests in the Agrigentum campaign, and following several naval battles, Rome attempted (256/255 BC) the second large scale land operation of the war. Seeking a swifter end to the war than the long sieges in Sicily would have provided, Rome decided to invade the Carthaginian colonies of Africa and usurp Carthage's supremacy in the Mediterranean Sea, consequently forcing Carthage to accept its terms.[33][46]

Battle of Cape Ecnomus

In order to initiate its invasion of Africa, the Roman Republic constructed a major fleet, comprising transports for the army and its equipment, and warships for protection. Carthage attempted to intervene with a fleet of 350 ships (according to Polybius),[47] but was defeated in the Battle of Cape Ecnomus.[48]

Regulus's raid

As a result of the battle, the Roman army, commanded by Marcus Atilius Regulus, landed in Africa and began ravaging the Carthaginian countryside.[49] The Siege of Aspis (or Clupea) was the first fighting on African land during the war. Regulus was next victorious at the Battle of Adys, forcing Carthage to sue for peace.[50] According to Polybius, the terms suggested were so heavy that Carthage decided they would be better off not under Roman rule. The negotiations failed but fortunately, for the Carthaginians, Xanthippus, a Spartan mercenary, returned to Carthage to reorganise its army.[33][51] Xanthippus defeated the Roman army and captured Regulus at the Battle of Tunis,[52][53] and then managed to cut off what remained of the Roman army from its base by re-establishing Carthaginian naval supremacy.[54][55]

Carthage's respite

The Romans, meanwhile, had sent a new fleet to pick up the survivors of its African expedition. Although the Romans defeated the Carthaginian fleet and were successful in rescuing their army in Africa, a storm destroyed nearly the entire Roman fleet on the return trip; the number of casualties in the disaster may have exceeded 90,000 men.[55] The Carthaginians took advantage of this to attack Agrigentum. They did not believe that they could hold the city, so they burned it and left.[56]

Renewed Roman offensive

The Romans were able to rally, however, and quickly resumed the offensive. With a new fleet of 140 ships, Rome returned to the strategy of taking the Carthaginian cities in Sicily one by one.[57]

Initial failure

Attacks began with naval assaults on Lilybaeum, the centre of Carthaginian power on Sicily, and a raid on Africa. Both efforts ended in failure.[58] The Romans retreated from Lilybaeum, and the Roman African force was caught in another storm and destroyed.[58]

Northern advance

The Romans, however, made great progress in the north. The city of Thermae was captured in 252 BC, enabling another advance on the port city of Panormus. The Romans attacked this city after taking Kephalodon in 251 BC. After fierce fighting, the Carthaginians were defeated and the city fell. With Panormus captured, much of western inland Sicily fell with it. The cities of Ietas, Solous, Petra, and Tyndaris agreed to peace with the Romans that same year.[59]

Northwestern expedition

The next year, the Romans shifted their attention to the north-west. They sent a naval expedition toward Lilybaeum. En route, the Romans seized and burned the Carthaginian hold-out cities of Selinous and Heraclea Minoa. This expedition to Lilybaeum was not successful, but attacking the Carthaginian headquarters demonstrated Roman resolve to take all of Sicily.[60] The Roman fleet was defeated by the Carthaginians at Drepana, forcing the Romans to continue their attacks from land. Roman forces at Lilybaeum were relieved, and Eryx, near Drepana, was seized thus menacing that important city as well.[61]

Following the conclusive naval victory off Drepana in 249 BC, Carthage ruled the seas as Rome was unwilling to finance the construction of yet another expensive fleet. Nevertheless, the Carthaginian faction that opposed the conflict, led by the land-owning aristocrat Hanno the Great, gained power and in 244 BC, considering the war to be over, started the demobilisation of the fleet, giving the Romans a chance to again attain naval superiority.[62]

|

Roman holdings or advances (arrows) Syracusan holdings |

Punic holdings (advance: red arrow) |

Conclusion

Stalemate in Sicily

At this point (247 BC[63]), Carthage sent general Hamilcar Barca (Hannibal's father) to Sicily. His landing at Heirkte (near Panormus) drew the Romans away to defend that port city and resupply point and gave Drepana some breathing room. Subsequent guerrilla warfare kept the Roman legions pinned down and preserved Carthage's toehold in Sicily, although Roman forces which bypassed Hamilcar forced him to relocate to Eryx, to better defend Drepana.[60]

Battle of the Aegates Islands

Perhaps in response to Hamilcar's raids, Rome built another fleet (paid for by donations from wealthy citizens). It was this fleet that rendered the Carthaginian success in Sicily futile, as the stalemate Hamilcar produced in Sicily became irrelevant following the Roman naval victory at the Battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 BC, where the new Roman fleet under consul Gaius Lutatius Catulus was victorious over an undermanned and hastily built Carthaginian fleet. Carthage lost most of its fleet and was economically incapable of funding another, or of finding manpower for the crews.[64]

Without naval support, Hamilcar Barca was cut off from Carthage and forced to negotiate peace and agree to evacuate Sicily.[65] It should be noted that Hamilcar Barca had a subordinate named Gesco conduct the negotiations with Lutatius, in order to create the impression that he had not really been defeated.[1][66]

Role of naval warfare

Due to the difficulty of operating in Sicily, most of the First Punic War was fought at sea, including the most decisive battles.[17] But one reason the war bogged down into stalemate on the landward side was because ancient navies were ineffective at maintaining seaward blockades of enemy ports. Consequently, Carthage was able to reinforce and re-supply its besieged strongholds, especially Lilybaeum, on the western end of Sicily. Both sides of the conflict had publicly funded fleets. This fact compromised Carthage and Rome's finances and eventually decided the course of the war.[67]

Despite the Roman victories at sea, the Roman Republic lost countless ships and crews during the war, due to both storms and battles. On at least two occasions (255 and 253 BC), whole fleets were destroyed in bad weather; the disaster off Camarina in 255 BC counted 270 ships and 119,280 men lost, the greatest single loss in history.Lazenby 1996, p. 162[68] One theory is that the weight of the corvus on the prows of the ships made the ships unstable and caused them to sink in bad weather. Later, as Roman experience in naval warfare grew, the corvus device was made attachable and detachable due to its impact on the navigability of the war vessels.[69]

Aftermath

Rome won the First Punic War after 23 years of conflict and in the end became the dominant naval power of the Mediterranean. In the aftermath of the war, both states were financially and demographically exhausted.[67] Corsica, Sardinia and Africa remained Carthaginian, but they had to pay a high war indemnity. Rome's victory was greatly influenced by its persistence. Moreover, the Roman Republic's ability to attract private investments in the war effort to fund ships and crews was one of the deciding factors of the war, particularly when contrasted with the Carthaginian nobility's apparent unwillingness to risk their fortunes for the common war effort.

Casualties

The exact number of casualties on each side is difficult to determine, due to bias in the historical sources.

According to sources (excluding land warfare casualties):[70]

- Rome lost 700 ships (in part to bad weather) with an unknown number of crew deaths.

- Carthage lost 500 ships with an unknown number of crew deaths.

Although uncertain, the casualties were heavy for both sides. Polybius commented that the war was, at the time, the most destructive in terms of casualties in the history of warfare, including the battles of Alexander the Great. Analysing the data from the Roman census of the 3rd century BC, Adrian Goldsworthy noted that, during the conflict, Rome lost about 50,000 male citizens. This excludes auxiliary troops and every other man in the army without citizen status, who would be outside the head count.[71][72]

Peace terms

The terms of the Treaty of Lutatius designed by the Romans were particularly heavy for Carthage, which had lost bargaining power following its defeat at the Aegates islands. Accordingly, Carthage agreed to:

- evacuate Sicily and the small islands west of it (Aegadian Islands).

- return its prisoners of war without ransom, while paying a heavy ransom of their own.

- refrain from attacking Syracuse and her allies.

- transfer a group of small islands north of Sicily (the Aeolian Islands and Ustica) to Rome.

- evacuate all of the small islands between Sicily and Africa (Pantelleria, Linosa, Lampedusa, Lampione and Malta).

- pay a 2,200 talent (66 tonnes/145,000 pounds) of silver indemnity in ten annual instalments, plus an additional indemnity of 1,000 talents (30 tonnes/66,000 pounds) immediately.[73]

Further clauses determined that the allies of each side would not be attacked by the other, no attacks were to be made by either side upon the other's allies and both sides were prohibited from recruiting soldiers within the territory of the other. This denied the Carthaginians access to any mercenary manpower from Italy and most of Sicily, although this later clause was temporarily abolished during the Mercenary War.

Political results

In the aftermath of the war, Carthage had insufficient state funds. Hanno the Great tried to induce the disbanded armies to accept diminished payment, but kindled a movement that led to an internal conflict, the Mercenary War. After a hard struggle from the combined efforts of Hamilcar Barca, Hanno the Great and others, the Punic forces were finally able to annihilate the mercenaries and the insurgents. However, during this conflict, Rome took advantage of the opportunity to strip Carthage of Corsica and Sardinia as well.[1]

Perhaps the most immediate political result of the First Punic War was the downfall of Carthage's naval power. Conditions signed in the peace treaty were intended to compromise Carthage's economic situation and prevent the city's recovery. The indemnity demanded by the Romans strained the city's finances and forced Carthage to look to other areas of influence for the money to pay Rome.[74]

Carthage, seeking to make up for the recent territorial losses and a plentiful source of silver to pay the large indemnity owed to Rome, turned its attention to Iberia; and in 237 BC, the Carthaginians, led by Hamilcar Barca, began a series of campaigns to expand their control over the peninsula. Though Hamilcar was killed in 229 BC, the offensive continued with the Carthaginians extending their power towards the Ebro valley and founding "New Carthage" in 228 BC. When Carthage besieged the Roman protected town of Saguntum in 218 BC, it ignited the Second Punic War with Rome.[75]

As for Rome, the end of the First Punic War marked the start of Rome's expansion beyond the Italian Peninsula. Sicily became the first Roman province (Sicilia) governed by a former praetor, instead of an ally. Sicily would become very important to Rome as a source of grain.[1] Importantly, Syracuse was granted nominal independent ally status for the lifetime of Hiero II, and was not incorporated into the Roman province of Sicily until after it was sacked by Marcus Claudius Marcellus during the Second Punic War.[76]

Notable leaders

- Adherbal, Carthaginian leading admiral

- Appius Claudius Caudex, Roman consul

- Aulus Atilius Calatinus, Roman dictator

- Gaius Duilius, Roman consul

- Gaius Lutatius Catulus, Roman consul

- Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina, Roman consul

- Hamilcar Barca, Carthaginian leading general

- Hannibal Gisco, Carthaginian general

- Hanno the Great, Carthaginian leading politician

- Hasdrubal the Fair, Carthaginian general

- Hiero II, tyrant of Syracuse

- Lucius Caecilius Metellus, Roman consul

- Marcus Atilius Regulus, Roman consul

- Publius Claudius Pulcher, Roman consul

- Xanthippus, Spartan mercenary in the service of Carthage

- Hannibal the Rhodian, Carthaginian privateer

Chronology

- 264 BC: The Mamertines seek assistance from Rome to replace Carthage's protection against the attacks of Hiero II of Syracuse.

- 263 BC: Hiero II is defeated by consul Manius Valerius Messalla and is forced to change allegiance to Rome, which recognises his position as King of Syracuse and the surrounding territory.

- 262 BC: Roman intervention in Sicily. The city of Agrigentum, occupied by Carthage, is besieged.

- 261 BC: Battle of Agrigentum, which results in a Roman victory and capture of the city. Rome decides to build a fleet to threaten Carthaginian domination at sea.

- 260 BC: First naval encounter (Battle of the Lipari Islands) is a disaster for Rome, but soon afterwards, Gaius Duilius wins the battle of Mylae with the help of the corvus engine.[1]

- 259 BC: The land fighting is extended to Sardinia and Corsica.

- 258 BC: Naval Battle of Sulci: Roman victory.

- 257 BC: Naval Battle of Tyndaris: Roman victory.

- 256 BC: Rome attempts to invade Africa and Carthage attempts to intercept the transport fleet. The resulting Battle of Cape Ecnomus is a major victory for Rome, which lands in Africa and advances on Carthage. The Battle of Adys is the first Roman success on African soil and Carthage sues for peace. Negotiations fail to reach agreement and the war continues.

- 255 BC: The Carthaginians employ a Spartan general, Xanthippus, to organise their defences and defeat the Romans at the Battle of Tunis. The Roman survivors are evacuated by a fleet to be destroyed soon afterwards, on their way back to Sicily.

- 254 BC: A new fleet of 140 Roman ships is constructed to substitute the one lost in the storm and a new army is levied. The Romans win a victory at Panormus, in Sicily, but fail to make any further progress in the war. Five Greek cities in Sicily defect from Carthage to Rome.

- 253 BC: The Romans pursue a policy of raiding the African coast east of Carthage. After an unsuccessful year the fleet heads for home. During the return to Italy the Romans are again caught in a storm and lose 150 ships.

- 251 BC: The Romans again win at Panormus over the Carthaginians, led by Hasdrubal. As a result of the recent losses, Carthage endeavours to strengthen its garrisons in Sicily and recapture Agrigentum. Romans begin siege of Lilybaeum.

- 249 BC: Rome loses almost a whole fleet in the Battle of Drepana. In the same year Hamilcar Barca accomplishes successful raids in Sicily and yet another storm destroys the remainder of the Roman ships. Aulus Atilius Calatinus is appointed dictator and sent to Sicily.

- 248 BC: Beginning of a period of low-intensity fighting in Sicily, without naval battles. This lull would last until 241 BC.

- 244 BC: With little to no naval engagements, Hanno the Great of Carthage advocates the demobilisation of large parts of the Carthaginian navy to save money. Carthage does so.

- 242 BC: Rome constructs another major battle fleet.

- 241 BC: On March 10, the Romans secure a decisive victory at the Battle of the Aegates Islands. Carthage negotiates peace terms and the First Punic War ends.[1]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sidwell & Jones 1997, p. 16.

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911. "Rome." vol 23 p628.

- ↑ Starr 1965, pp. 464–465.

- 1 2 Starr 1965, p. 465.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911. "Carthage." vol 5 p429.

- ↑ Starr 1965, p. 478.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911. "Carthage." Vol 5 p428.

- ↑ John Iliffe (13 August 2007). Africans: The History of a Continent. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-139-46424-6. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911. "Carthage." Vol 5 p427.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911. "Sicily." Vol 25 p25.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, p. 165.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:9.7-9.8.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, p. 167.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:10.7-10.9.

- ↑ Starr 1965, p. 479; Warmington 1993, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:11.3.

- 1 2 Niebuhr 1844, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:11.2-11.4.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:11.12-11.14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Warmington 1993, p. 171.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:16.6-16.8.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, pp. 171–172.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:17.4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Polybius. The Histories, 1:19.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, p. 172.

- ↑ Zoch 2000, pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Lazenby 1996, p. 49.

- ↑ Polybius, The Histories, I.20–21

- 1 2 Reynolds 1998, p. 22.

- ↑ Roberts 2006, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, p. 173.

- ↑ Wallinga 1956, pp. 73–77.

- 1 2 3 Starr 1965, p. 481.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:22.3-22.11.

- ↑ Addington 1990, p. 29.

- 1 2 Polybius. The Histories, 1:23.

- ↑ Lazenby 1996, p. 70.

- ↑ Polybius. The General History of Polybius, Book I (p. 29).

- ↑ Bagnall 2002, p. 63.

- ↑ Lazenby 1996, p. 73.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:24.1-24.2.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:24.3-24.4.

- ↑ Lazenby 1996, p. 75.

- ↑ Lucio Cornelio Scipione

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:24.10-24.13.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, p. 175.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:25.9.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, p. 176.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, p. 177.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:33–34.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, pp. 177–178.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:36.5-36.9.

- 1 2 Warmington 1993, p. 178.

- ↑ Smith 1854, p. 76.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, pp. 178–179.

- 1 2 Warmington 1993, p. 179.

- ↑ Lazenby 1996, p. 116.

- 1 2 Smith 1854, p. 788.

- ↑ Lazenby 1996, p. 148.

- ↑ Bagnall 2002, p. 80.

- ↑ Goldsworthy 2001, p. 95.

- ↑ Mokhtar 1981, p. 457.

- ↑ Bedford & Bradford 2001, p. 174.

- ↑ Lendering, Jona (1995–2010). "First Punic War: Chronology". Livius: Articles on Ancient History. Retrieved 27 November 2010. .

- 1 2 Bringmann 2007, p. 127.

- ↑ Dupuy 1984.

- ↑ Penrose 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:63.6.

- ↑ Goldsworthy 2007, Backcover.

- ↑ Goodrich 1864, p. 75.

- ↑ Polybius. The Histories, 1:62.7-63.3.

- ↑ Fields 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Collins 1998, p. 13.

- ↑ Allen & Myers 1890, p. 111.

Sources

- Addington, Larry H. (1990). The Patterns of War through the Eighteenth Century. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20551-4.

- Allen, William Francis; Myers, Philip Van Ness (1890). Ancient History for Colleges and High Schools: Part II – A Short History of the Roman People. Boston, United States of America: Ginn & Company. ISBN 978-1-143-05928-5.

- Bagnall, Nigel (2002). The Punic Wars, 264–146 BC. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-355-1.

- Bedford, Alfred S.; Bradford, Pamela M. (2001). With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95259-2.

- Bringmann, Klaus (2007). A History of the Roman Republic. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-3370-6.

- Collins, Roger (1998). Spain: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285300-7.

- Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt (1984). The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare. Da Capo Press, Inc. ISBN 0-306-80384-4.

- Fields, Nic (2007). The Roman Army of the Punic Wars 264–146 BC. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-145-1.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith (2007). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36642-0.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith (2001). The Punic Wars. Cassel. ISBN 978-0-304-35284-5.

- Goodrich, Samuel Griswold (1864). A Pictorial History of Ancient Rome: With Sketches of the History of Modern Italy (PDF). Philadelphia: E. H. Butler & Co. ISBN 978-1-147-45071-2.

- Lazenby, John Francis (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2673-6. OCLC 34371250.

- Mokhtar, Gamal (1981). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-435-94805-9.

- Niebuhr, Barthold Georg (1844). Lectures on the history of Rome from the first Punic war to the death of Constantine. In a series of lectures, including an introductory course on the sources and study of Roman history, Volume 2 (PDF). Taylor & Walton. ISBN 1-150-67678-7.

- Penrose, Jane (2008). Rome and Her Enemies: An Empire Created and Destroyed by War. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-336-5.

- Reynolds, Clark G. (1998). Navies in History. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-715-5.

- Roberts, Peter (2006). Ancient History, Book 2. Pascal Press. ISBN 1-74125-179-6.

- Sidwell, Keith C.; Jones, Peter V. (1997). The World of Rome: An Introduction to Roman Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38600-4.

- Smith, William (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (PDF). Little, Brown & Co. ISBN 978-1-84511-001-7.

- Starr, Chester G. (1965). A History of the Ancient World. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506628-6.

- Wallinga, Herman Tammo (1956). The Boarding-bridge of the Romans: Its Construction and its Function in the Naval Tactics of the First Punic War. J. B. Wolters Groningen.

- Warmington, Brian Herbert (1993) [1960]. Carthage. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. ISBN 978-1-56619-210-1.

- Zoch, Paul A. (2000). Ancient Rome: An Introductory History. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3287-6.

Further reading

- Armstrong, Jeremy. 2016. Early Roman Warfare: From the Regal Period to the First Punic War. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Military.

- Biggs, T. 2017. "Primus Romanorum: Origin Stories, Fictions of Primacy, and the First Punic War." Classical Philology 112(3): 350–67.

- Cornell, Tim J. 1995. The beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000–264 BC). London: Routledge.

- Forsythe, Gary. 2005. A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian K. 2002. The Punic Wars. London: Cassell.

- Hoyos, Dexter. 1998. Unplanned wars: The origins of the First and Second Punic Wars. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- ————, ed. 2011. A companion to the Punic Wars. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lazenby, J. F. 1996. The First Punic War: A military history. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Punic War. |

| Library resources about First Punic War |