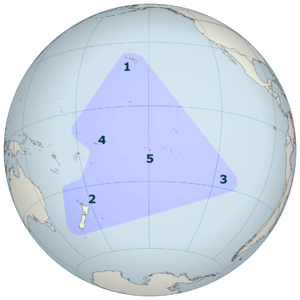

Polynesian Triangle

The Polynesian Triangle is a region of the Pacific Ocean with three island groups at its corners: Hawaiʻi (formerly "the Sandwich Islands"), Easter Island (Rapa Nui) and New Zealand (Aotearoa). It is often used as a simple way to define Polynesia.

Outside the triangle, there are traces of Polynesian settlement as far north as Necker Island (Mokumanamana), as far east as Salas y Gómez Island (Motu Motiro Hiva), and as far south as Enderby Island (Motu Maha). There was also once Polynesian settlement on Norfolk Island and Kermadec Island (Rangitahua). However, by the time the Europeans first arrived, these islands were all uninhabited.

Today, the most numerous Polynesian peoples are the Māori, Hawaiians, Tongans, Samoans, and Tahitians. The native languages of this vast triangle are Polynesian languages, which are classified by linguists as part of the Oceanic subgroup of Malayo-Polynesian. They ultimately derive from the proto-Austronesian language spoken in Southeast Asia 5,000 years ago. There are also numerous Polynesian outlier islands outside the triangle in neighboring Melanesia and Micronesia.

History

Anthropologists believe that all modern Polynesian cultures descend from a single protoculture established in the South Pacific by migrant Malayo-Polynesian people (see also Lapita). There is also some evidence that Polynesians ventured as far east as the Isla Salas y Gómez and as far south as the subantarctic islands to the south of New Zealand, however none of these islands are reckoned with Polynesia proper, as no viable settlements have survived. A shard of pottery has been found in the Antipodes Islands, and is now in the Te Papa museum in Wellington, and there are also remains of a Polynesian settlement dating back to the 13th century on Enderby Island in the Auckland Islands.[1][2][3][4]

In contrast to the shape of a triangle, another theory states that the geography of Polynesian society and navigation pathways more accurately resemble the geometric qualities of an octopus with head centred on Ra'iātea (French Polynesia) and tentacles spread out across the Pacific.[5] In Polynesian oral tradition the octopus is known by various names such as Taumata-Fe'e-Fa'atupu-Hau (Grand Octopus of Prosperity), Tumu-Ra'i-Fenua (Beginning-of-Heaven-and-Earth) and Te Wheke-a-Muturangi (The Octopus of Muturangi).

See also

References

- ↑ O'Connor, Tom Polynesians in the Southern Ocean: Occupation of the Auckland Islands in Prehistory in New Zealand Geographic 69 (September–October 2004): 6-8)

- ↑ Anderson, Atholl J., & Gerard R. O'Regan To the Final Shore: Prehistoric Colonisation of the Subantarctic Islands in South Polynesia in Australian Archaeologist: Collected Papers in Honour of Jim Allen Canberra: Australian National University, 2000. 440-454.

- ↑ Anderson, Atholl J., & Gerard R. O'Regan The Polynesian Archaeology of the Subantarctic Islands: An Initial Report on Enderby Island Southern Margins Project Report. Dunedin: Ngai Tahu Development Report, 1999

- ↑ Anderson, Atholl J. Subpolar Settlement in South Polynesia Antiquity 79.306 (2005): 791-800

- ↑ E. Tetahiotupa, Au gré des vents et des courants (Éditions des Mers Australes) 2009, https://www.tahiti-infos.com/Pourquoi-le-Triangle-polynesien-est-une-pieuvre_a135121.html