Paramyxoviridae

| Paramyxoviridae | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group V ((−)ssRNA) |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Paramyxoviridae |

| Genera | |

Paramyxoviridae is a family of viruses in the order Mononegavirales. Vertebrates serve as natural hosts; no known plants serve as vectors.[1] There are currently 49 species in this family, divided among 7 genera. Diseases associated with this negative-sense single-stranded RNA virus family include measles, mumps, and respiratory tract infections.[2][3][4]

Taxonomy

Table legend: "*" denotes type species.

Notes

Beilong virus is now known to be a member of the family.[6] It was isolated from rat kidney and its pathogenic potential is unknown. J virus is very similar to Beilong virus and probably belongs in the same genus. Both have features that differ from the other genera in this family. Tailam virus may also belong in this genus. The genus Jeilongvirus has been proposed for these three viruses.[7]

The relations between the Salmon paramyxovirus and the others have been poorly studied to date and their relationship to the other members of this genus is not currently known.

Another virus in this family is Anaconda paramyxovirus.[8]

Bank vole virus, Mossman virus and Nariva virus are three paramyxovirus that probably belong in a new genus.[9]

Life cycle

Viral replication is cytoplasmic. Entry into the host cell is achieved by virus attachment to host cell. Replication follows the negative stranded RNA virus replication model. Negative stranded RNA virus transcription, using polymerase stuttering is the method of transcription. Translation takes place by leaky scanning, ribosomal shunting, and RNA termination-reinitiation. The virus exits the host cell by budding. Human, vertebrates, and birds serve as the natural host. Transmission route is air borne particles.[2] Paramyxoviridae are able to undergo mRNA editing, which produces different proteins from the same mRNA transcript by slipping back one base to read off in a different ORF due to the presence of secondary structures such as pseudoknots.[10] Paramyxoviridae also undergo translational stuttering in order to produce the poly(A) tail at the end of mRNA transcripts by repeatedly moving back one nucleotide at a time at the end of the RNA template[11]

| Genus | Host details | Tissue tropism | Entry details | Release details | Replication site | Assembly site | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avulavirus | Birds | None | Glycoprotein | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Contact: feces; contact: secretions (from nose, mouth, eyes) |

| Morbillivirus | Humans; dogs; cats; cetaceans | None | Glycoprotein | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Aerosols |

| Aquaparamyxovirus | Fish | None | Glycoprotein | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Unknown |

| Henipavirus | Bats | None | Glycoprotein | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Zoonosis; animal bite |

| Respirovirus | Rodents; humans | None | Glycoprotein | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Aerosols |

| Rubulavirus | Humans; apes; pigs; dogs | None | Glycoprotein | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Aerosols; saliva |

| Ferlavirus | Unknown | None | Glycoprotein | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Unknown |

Physical structure

Virions are enveloped and can be spherical or pleomorphic and capable of producing filamentous virions. The diameter is around 150 nm. Genomes are linear, around 15kb in length.[2] Fusion proteins and attachment proteins appear as spikes on the virion surface. Matrix proteins inside the envelope stabilise virus structure. The nucleocapsid core is composed of the genomic RNA, nucleocapsid proteins, phosphoproteins and polymerase proteins.

| Genus | Structure | Symmetry | Capsid | Genomic arrangement | Genomic segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avulavirus | Spherical | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite | |

| Morbillivirus | Spherical | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite | |

| Aquaparamyxovirus | Spherical | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite | |

| Henipavirus | Spherical | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite | |

| Respirovirus | Spherical | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite | |

| Rubulavirus | Pleomorphic | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite | |

| Ferlavirus | Spherical | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite |

Genome structure

The genome is non-segmented negative-sense RNA, 15–19 kilobases in length and contains 6–10 genes. Extracistronic (non-coding) regions include:

- A 3’ leader sequence, 50 nucleotides in length, which acts as a transcriptional promoter.

- A 5’ trailer sequence, 50–161 nucleotides long

- Intergenomic regions between each gene, which are three nucleotides long for morbilliviruses, respiroviruses and henipaviruses, and variable length (1-56 nucleotides) for rubulaviruses.

Each gene contains transcription start/stop signals at the beginning and end, which are transcribed as part of the gene.

Gene sequence within the genome is conserved across the family due to a phenomenon known as transcriptional polarity (see Mononegavirales) in which genes closest to the 3’ end of the genome are transcribed in greater abundance than those towards the 5’ end. This is a result of structure of the genome. After each gene is transcribed, the RNA-Dependent RNA polymerase pauses to release the new mRNA when it encounters an intergenic sequence. When the RNA polymerase is paused, there is a chance that it will dissociate from the RNA genome. If it dissociates, it must reenter the genome at the leader sequence, rather than continuing to transcribe the length of the genome. The result is that the further downstream genes are from the leader sequence, the less they will be transcribed by RNA polymerase.

Evidence for a single promoter model was verified when viruses were exposed to UV light. UV radiation can cause dimerization of RNA, which prevents transcription by RNA polymerase. If the viral genome follows a multiple promoter model, the level inhibition of transcription should correlate with the length of the RNA gene. However, the genome was best described by a single promoter model. When paramyxovirus genome was exposed to UV light, the level of inhibition of transcription was proportional to the distance from the leader sequence. That is, the further the gene is from the leader sequence, the greater the chance of RNA dimerization inhibiting RNA polymerase.

The virus takes advantage of the single promoter model by having its genes arranged in relative order of protein needed for successful infection. For example, nucleocapsid protein, N, is needed in greater amounts than RNA polymerase, L.

Viruses in the Paramyxoviridae family are also antigenically stable, meaning that the glycoproteins on the viruses are consistent between different strains of the same type. There are two reasons for this phenomenon. The first is that the genome is non-segmented and thus cannot undergo genetic reassortment. In order for this process to occur, segments are needed as reassortment happens when segments from different strains are mixed together to create a new strain. With no segments, nothing can be mixed with one another and so there is no antigenic shift. The second reason relates to the idea of antigenic drift. Since RNA dependent RNA polymerase does not have an error checking function, many mutations are made when the RNA is processed. These mutations build up and eventually new strains are created. Due to this concept, one would expect that paramyxoviruses should not be antigenically stable; however, the opposite is seen to be true. The main hypothesis behind why the viruses are antigenically stable is that each protein and amino acid has an important function. Thus, any mutation would lead to a decrease or total loss of function, which would in turn cause the new virus to be less efficient. These viruses would not be able to survive as long compared to the more virulent strains, and so would die out.

Many paramyxovirus genomes follow the "rule of six". The total length of the genome is almost always a multiple of six. This is probably due to the advantage of having all RNA bound by N protein (since N binds hexamers of RNA). If RNA is left exposed, the virus does not replicate efficiently. Members of the sub-family Pneumovirinae do not follow this rule

The gene sequence is:

- Nucleocapsid – Phosphoprotein – Matrix – Fusion – Attachment – Large (polymerase)

Proteins

- N – the nucleocapsid protein associates with genomic RNA (one molecule per hexamer) and protects the RNA from nuclease digestion

- P – the phosphoprotein binds to the N and L proteins and forms part of the RNA polymerase complex

- M – the matrix protein assembles between the envelope and the nucleocapsid core, it organizes and maintains virion structure

- F – the fusion protein projects from the envelope surface as a trimer, and mediates cell entry by inducing fusion between the viral envelope and the cell membrane by class I fusion. One of the defining characteristics of members of the family Paramyxoviridae is the requirement for a neutral pH for fusogenic activity.

- H/HN/G – the cell attachment proteins span the viral envelope and project from the surface as spikes. They bind to proteins on the surface of target cells to facilitate cell entry. Proteins are designated H (hemagglutinin) for morbilliviruses as they possess haemagglutination activity, observed as an ability to cause red blood cells to clump in laboratory tests. HN (Hemagglutinin-neuraminidase) attachment proteins occur in respiroviruses, rubulaviruses and avulaviruses. These possess both haemagglutination and neuraminidase activity, which cleaves sialic acid on the cell surface, preventing viral particles from reattaching to previously infected cells. Attachment proteins with neither haemagglutination nor neuraminidase activity are designated G (glycoprotein). These occur in henipaviruses.

- L – the large protein is the catalytic subunit of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP)

- Accessory proteins – a mechanism known as RNA editing (see Mononegavirales) allows multiple proteins to be produced from the P gene. These are not essential for replication but may aid in survival in vitro or may be involved in regulating the switch from mRNA synthesis to antigenome synthesis.

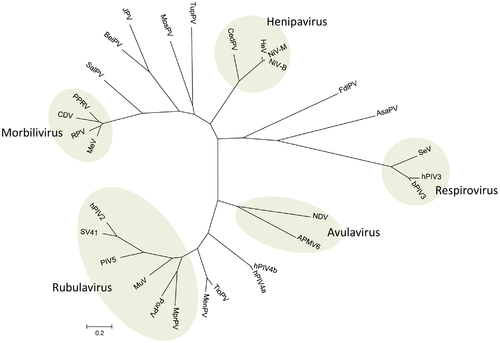

Pathogenic paramyxoviruses

Virus names are as follows: avian paramyxovirus 6 (APMV-6); Atlantic salmon paramyxovirus; Beilong virus (BeiPV) ; bovine parainfluenza virus 3 (bPIV3); canine distemper virus (CDV); Cedar virus (CedV); Fer-de-lance virus (FdlPV) ; Hendra virus (HeV); human parainfluenza virus 2 (hPIV2); human parainfluenza virus 3 (hPIV3) ; human parainfluenza virus 4a (hPIV4a) ; human parainfluenza virus 4b (hPIV4b); J virus (JPV); Menangle virus (MenPV); measles virus (MeV); Mossman virus (MosPV); Mapuera virus (MprPV); mumps virus (MuV); Newcastle disease virus (NDV); Nipah virus, Bangladesh strain (NiV-B); Nipah virus, Malaysian strain (NiV-M); parainfluenza virus 5 (PIV5); peste-des-petits-ruminants (PPRV); porcine rubulavirus (PorPV); rinderpest virus (RPV); Salem virus (SalPV); Sendai virus (SeV); simian virus 41 (SV41); Tioman virus (TioPV); tupaia paramyxovirus (TupPV).[12]

A number of important human diseases are caused by paramyxoviruses. These include mumps, measles, which caused around 733,000 deaths in 2000,[13] and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which is the major cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants and children.

The human parainfluenza viruses (HPIV) are the second most common causes of respiratory tract disease in infants and children. There are four types of HPIVs, known as HPIV-1, HPIV-2, HPIV-3 and HPIV-4. HPIV-1 and HPIV-2 may cause cold-like symptoms, along with croup in children. HPIV-3 is associated with bronchiolitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia. HPIV-4 is less common than the other types, and is known to cause mild to severe respiratory tract illnesses.[14]

Paramyxoviruses are also responsible for a range of diseases in other animal species, for example canine distemper virus (dogs), phocine distemper virus (seals), cetacean morbillivirus (dolphins and porpoises), Newcastle disease virus (birds), and rinderpest virus (cattle). Some paramyxoviruses such as the henipaviruses are zoonotic pathogens, occurring naturally in an animal host, but also able to infect humans.

Hendra virus (HeV) and Nipah virus (NiV) in the genus Henipavirus have emerged in humans and livestock in Australia and Southeast Asia. Both viruses are contagious, highly virulent, and capable of infecting a number of mammalian species and causing potentially fatal disease. Due to the lack of a licensed vaccine or antiviral therapies, HeV and NiV are designated as biosafety level (BSL) 4 agents. The genomic structure of both viruses is that of a typical paramyxovirus.[15]

Diversity and evolution

In the past few decades, paramyxoviruses have been discovered from terrestrial, volant and aquatic animals, demonstrating a vast host range and great viral genetic diversity. As molecular technology advances and viral surveillance programs are implemented, the discovery of new viruses in this group is increasing.[4]

The evolution of paramyxoviruses is still debated. Using pneumoviruses (mononegaviral family Pneumoviridae) as an outgroup, paramyxoviruses can be divided into two clades: one consisting of avulaviruses and rubulaviruses and one consisting of respiroviruses, henipaviruses, and morbilliviruses.[16] Within the second clade the respiroviruses appear to be the basal group. The respirovirus-henipavirus-morbillivirus clade may be basal to the avulavirus-rubulavirus clade.

See also

References

- ↑ Fields virology. Fields, Bernard N., Knipe, David M. (David Mahan), 1950-, Howley, Peter M., (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2013. p. 883. ISBN 9781451105636. OCLC 825740706.

- 1 2 3 "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ ICTV. "Virus Taxonomy: 2014 Release". Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- 1 2 Samal, SK, ed. (2011). The Biology of Paramyxoviruses. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-85-1.

- ↑ Amarasinghe, Gaya K.; Bào, Yīmíng; Basler, Christopher F.; Bavari, Sina; Beer, Martin; Bejerman, Nicolás; Blasdell, Kim R.; Bochnowski, Alisa; Briese, Thomas (2017-04-07). "Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: update 2017". Archives of Virology. doi:10.1007/s00705-017-3311-7. ISSN 1432-8798. PMID 28389807.

- ↑ Woo PC, Lau SK, Wong BH, Wu Y, Lam CS, Yuen KY (June 2012). "Novel variant of Beilong Paramyxovirus in rats, China". Emerging Infect. Dis. 18 (6): 1022–4. doi:10.3201/eid1806.111901. PMC 3358166. PMID 22607652.

- ↑ Woo PC, Wong AY, Wong BH, Lam CS, Fan RY, Lau SK, Yuen KY (2016). "Comparative genome and evolutionary analysis of naturally occurring Beilong virus in brown and black rats". Infect. Genet. Evol. 45: 311–9. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2016.09.016. PMID 27663719.

- ↑ Woo PC, Martelli P, Hui SW, Lau CC, Groff JM, Fan RY, Lau SK, Yuen KY (2017). "Anaconda paramyxovirus infection in an adult green anaconda after prolonged incubation: Pathological characterization and whole genome sequence analysis". Infect. Genet. Evol. 51: 239–244. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2017.04.008. PMID 28404483.

- ↑ Alkhovsky S, Butenko A, Eremyan A, Shchetinin A (2017) Genetic characterization of bank vole virus (BaVV), a new paramyxovirus isolated from kidneys of bank voles in Russia. Arch Virol

- ↑ Marsh GA, de Jong C, Barr JA, Tachedjian M, Smith C, Middleton D, Yu M, Todd S, Foord AJ, Haring V, Payne J, Robinson R, Broz I, Crameri G, Field HE, Wang LF (2012). "Cedar virus: a novel Henipavirus isolated from Australian bats". PLoS Pathogens. 8 (8): e1002836. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002836. PMC 3410871. PMID 22879820.

- ↑ "Global Measles Mortality, 2000--2008". www.cdc.gov.

- ↑ "CDC – HPIVs – Overview of Human Parainfluenza Viruses". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ Sawatsky (2008). "Hendra and Nipah Virus". Animal Viruses: Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-22-6.

- ↑ McCarthy AJ, Goodman SJ (January 2010). "Reassessing conflicting evolutionary histories of the Paramyxoviridae and the origins of respiroviruses with Bayesian multigene phylogenies". Infect. Genet. Evol. 10 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2009.11.002. PMID 19900582.

External links

- Paramyxoviruses (1998) — morphology, genome, replication, pathogenesis (special access required)

- "Hendra virus has a growing family tree". CSIRO Paramyxovirus press release. 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-08-04.

- Animal viruses

- Paramyxoviridae Genomes Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center

- Viralzone: Paramyxoviridae

- ICTV

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Paramyxoviridae