Eastern equine encephalitis

| Eastern equine encephalitis |

|---|

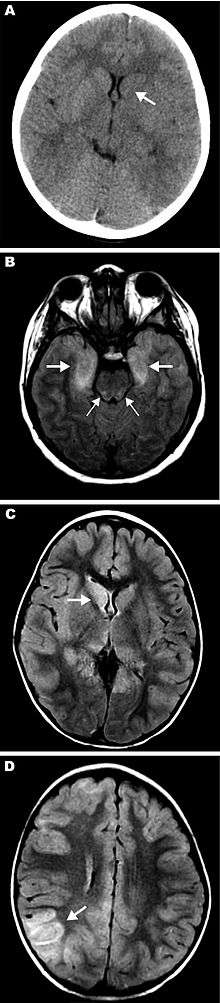

Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), commonly called Triple E or, sleeping sickness (not to be confused with trypanosomiasis) is a zoonotic alphavirus and arbovirus present in North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean. EEE was first recognized in Massachusetts, United States, in 1831 when 75 horses died mysteriously of viral encephalitis. Epizootics in horses have continued to occur regularly in the United States. It can also be identified in asses and zebras. Due to the rarity of the disease, its occurrence can cause economic impact in relation to the loss of horses and poultry.[1] EEE is found today in the eastern part of the country and is often associated with coastal plains. It can most commonly be found in East and Gulf coast states.[2] In Florida, about one to two human cases are reported a year, although over 60 cases of equine encephalitis are reported. Some years in which conditions are favorable for the disease, the number of equine cases is over 200.[3] Diagnosing equine encephalitis is challenging because many of the symptoms are shared with other illnesses and patients can be asymptomatic. Confirmations may require a sample of cerebral spinal fluid or brain tissue, although CT scans and MRI scans are used to detect encephalitis. This could be an indication that the need to test for EEE is necessary. If a biopsy of the cerebral spinal fluid is taken, it is sent to a specialized laboratory for testing.[4]

EEEV is closely related to Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus and western equine encephalitis virus.

Signs and symptoms

The virus can progress either systematically and encephalitically, depending on the person's age. Encephalitic disease involves swelling of the brain and can be asymptomatic, while the systemic illness occurs very abruptly. Those with the systemic illness usually recover within 1-2 weeks. While the encephalitis is more common among infants, in adults and children it usually manifests after experiencing the systemic illness.[2] Symptoms include high fever, muscle pain, altered mental status, headache, meningeal irritation, photophobia, and seizures, which occur 3-10 days after the bite of an infected mosquito. Due to the virus's effect on the brain, patients who survive can be left with mental and physical impairments, such as personality disorders, paralysis, seizures, and intellectual impairment [2]

Cause

Virus

| Disease - eastern equine encephalomyelitis | |

|---|---|

| |

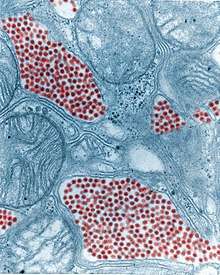

| Colourised TEM micrograph of a mosquito salivary gland: The virus particles (virions) are coloured red. (83,900x magnification) | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group IV ((+)ssRNA) |

| Family: | Togaviridae |

| Genus: | Alphavirus |

| Species: | Eastern equine encephalitis virus |

The causative agent, later identified as a togavirus, was first isolated from infected horse brains in 1933. In 1938, the first confirmed human cases were identified when 30 children died of encephalitis in the Northeastern United States. These cases coincided with outbreaks in horses in the same regions. The fatality rate in humans is 33%, and currently no cure is known for human infections. This virus has four variations in the types in lineage. The most common to the human disease is Group 1, which is considered to be endemic in North American and the Caribbean, while the other three lineages, Groups IIA, IIB, and III, are typically found in Central and South America, causing equine illness.[2]

These two clades may actually be distinct viruses.[5] The North American strains appear to be monotypic with a mutation rate of 2.7 × 10−4 substitutions/site/year (s/s/y). It appears to have diverged from the other strains 922 to 4,856 years ago. The other strains are divided into two main clades and a third smaller one. The two main clades diverged between 577 and 2,927 years ago. The mutation rate in the genome has been estimated to be 1.2 × 10−4 s/s/y.

Lifecycle

EEE is capable of infecting a wide range of animals, including mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. The virus is maintained in nature through a bird—mosquito cycle. Two mosquito species are primarily involved in this portion of the cycle; they are Culiseta melanura and Cs. morsitans. These mosquitoes feed on the blood of birds. The numbers of virus found in nature increase throughout the summer as more birds and more mosquitoes become infected.

Transmission of EEEV to mammals (including humans) occurs via other mosquitoes, species that feed upon the blood of both birds and mammals. These other mosquitoes are called bridge vectors because they carry the virus from the avian hosts to other types of hosts, particularly mammals. The bridge vectors include Aedes vexans, Coquillettidia perturbans, Ochlerotatus canadensis, and Ochlerotatus sollicitans. Ochlerotatus canadensis also frequently bites turtles.

Humans, horses, and most other infected mammals do not circulate enough virus in their blood to infect additional mosquitoes. There have been some cases where EEEV has been contracted through lab exposures or from exposure of the eyes, lungs or skin wounds to brain or spinal cord matter from infected animals.

Prevention

The disease can be prevented in horses with the use of vaccinations. These vaccinations are usually given together with vaccinations for other diseases, most commonly WEE, VEE, and tetanus. Most vaccinations for EEE consist of the killed virus. For humans there is no vaccine for EEE so prevention involves reducing the risk of exposure. Using repellent, wearing protective clothing, and reducing the amount of standing water is the best means for prevention[2]

Treatment and prognosis

No cure for EEE has been found. Treatment consists of corticosteroids, anticonvulsants, and supportive measures (treating symptoms)[6] such as intravenous fluids, tracheal intubation, and antipyretics. About 4% of humans known to be infected develop symptoms, with a total of about six cases per year in the US.[6] A third of these cases die, and many survivors suffer permanent brain damage.[7]

Epidemiology

Several states in the Northeast US have seen increased virus activity since 2004. Between 2004 and 2006, at least 10 human cases of EEE were reported in Massachusetts. In 2006, about 500,000 acres (2,000 km2) in southeastern Massachusetts were treated with mosquito adulticides to reduce the risk of humans contracting EEE. Several human cases have been reported in New Hampshire, as well.[8][9]

In October 2007, a citizen of Livingston, West Lothian, Scotland became the first European victim of this disease. The man had visited New Hampshire during the summer of 2007 on a fishing vacation, and was diagnosed as having EEE on 13 September 2007. He fell ill with the disease on 31 August 2007, just one day after flying home.[10]

On July 19, 2012, the virus was identified in a mosquito of the species Coquillettidia perturbans in Nickerson State Park on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. On July 28, 2012, the virus was found in mosquitos in Pittsfield, Massachusettes.[11]

Biological weapon

EEEV was one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological-weapons program.[12]

Other animals

After inoculation by the vector, the virus travels via lymphatics to lymph nodes, and replicates in macrophages and neutrophils, resulting in lymphopenia, leukopenia, and fever. Subsequent replication occurs in other organs leading to viremia. Symptoms in horses occur 1-3 weeks after infection, and begins with a fever that may reach as high as 106°F (41°C). The fever usually lasts for 24–48 hours.

Nervous signs appear during the fever that include sensitivity to sound, periods of excitement, and restlessness. Brain lesions appear, causing drowsiness, drooping ears, circling, aimless wandering, head pressing, inability to swallow, and abnormal gait. Paralysis follows, causing the horse to have difficulty raising its head. The horse usually suffers complete paralysis and death 2-4 days after symptoms appear. Mortality rates among horses with the eastern strain range from 70 to 90%.

References

- ↑ "Eastern Equine Encephalomyelitis" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Eastern Equine Encephalitis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ↑ "Eastern Equine Encephalitis". Florida Health. Florida Health. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ↑ Deresiewicz RL, Thaler SJ, Hsu L, Zamani AA (1997). "Clinical and neuroradiographic manifestations of eastern equine encephalitis". N. Engl. J. Med. 336 (26): 1867–74. doi:10.1056/NEJM199706263362604. PMID 9197215.

- ↑ Arrigo NC, Adams AP, Weaver SC (January 2010). "Evolutionary patterns of eastern equine encephalitis virus in North versus South America suggest ecological differences and taxonomic revision". J. Virol. 84 (2): 1014–25. doi:10.1128/JVI.01586-09. PMC 2798374. PMID 19889755.

- 1 2 "Eastern Equine Encephalitis". CDC. August 16, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Eastern Equine Encephalitis Fact Sheet". CDC. August 16, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ↑ Zheng, Y. (August 16, 2008). "Mosquito-borne virus infects 2d in Mass". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ the Boston Globe City; Region Desk (August 31, 2006). "Middleborough boy with EEE dies". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ "Man in coma after mosquito bite". BBC News. October 8, 2007.

- ↑ Kane, T. (July 27, 2012). "Rare, deadly virus found in mosquitoes in Pittsfield". News10.

- ↑ "Chemical and Biological Weapons: Possession and Programs Past and Present". James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Middlebury College. April 9, 2002. Archived from the original on October 2, 2001. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

Further reading

- "Eastern Equine Encephalitis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Source for a portion of this information: Evans, J.W.; Borton, A.; Hintz, H.F.; Van Vleck, L.D. (1977). The Horse. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0716704919.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- "Togaviridae". Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR).

- Joseph W. Beard Papers at Duke University Medical Center Archives