Jean-Baptiste Say

| Jean-Baptiste Say | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

5 January 1767 Lyon, France |

| Died |

15 November 1832 (aged 65) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Field | Political economy |

| School or tradition | Classical liberalism |

| Influences | Richard Cantillon, Adam Smith |

| Contributions | Say's Law |

Jean-Baptiste Say (French: [ʒãbatist sɛ]; 5 January 1767 – 15 November 1832) was a French economist and businessman who had classically liberal views and argued in favor of competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. He is best known for Say's law, also known as the law of markets, which he popularized. Scholars disagree on the surprisingly subtle question of whether it was Say who first stated what we now call Say's law.[1][2]

Biography

Say was born in Lyon. His father, Jean-Etienne Say, was born to a Protestant family, which had moved from Nîmes to Geneva for some time in consequence of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Say was intended to follow a commercial career and in 1785 was sent with his brother Horace to complete his education in England. He lodged for a time in Croydon and afterwards (following a return visit to France) in Fulham. During the latter period, he was employed successively by two London-based firms of sugar merchants, James Baillie & Co and Samuel and William Hibbert.[3][4] At the end of 1786, he accompanied Samuel Hibbert on a voyage to France which ended in December with Hibbert's death in Nantes. Say returned to Paris, where he found employment in the office of a life assurance company directed by Étienne Clavière. His brother, Louis Auguste (1774–1840), also became an economist.

His first literary attempt was a pamphlet on the liberty of the press, published in 1789. He later worked under Mirabeau on the Courrier de Provence. In 1792, he took part as a volunteer in the campaign of Champagne. In 1793, he assumed in keeping with French Revolutionary fashion the pseudonym Atticus and became secretary to Clavière, then finance minister.

In 1793, Say married Mlle Deloche, daughter of a former lawyer. From 1794 to 1800, he edited a periodical, entitled La Decade philosophique, litteraire, et politique, in which he expounded the doctrines of Adam Smith. He had by this time established his reputation as a publicist and when the consular government was established in 1799 he was selected as one of the 100 members of the Tribunat, resigning the editorship of the Decade.

In 1800, he published Olbie, ou essai sur les moyens de réformer les mœurs d'une nation. In 1803, he published his principal work, the Traité d'économie politique ou simple exposition de la manière dont se forment, se distribuent et se composent les richesses. In 1804, having proved unwilling to compromise his convictions in the interests of Napoleon, he was removed from the office of tribune. He turned to industrial activities and after having familiarised himself with the processes of cotton manufacture he established a spinning-mill at Auchy-lès-Hesdin in the Pas de Calais, which employed some 4–500 people, mainly women and children. He devoted his leisure time to revising his economic treatise, which had been out of print for some time, but the system of state censorship in place prevented him from republishing it.

In 1814, he "availed himself" (to use his own words) of the relative liberty arising from the entrance of the allied powers into France to bring out a second edition of the work dedicated to the emperor Alexander I of Russia, who had professed himself his pupil. In the same year, the French government sent him to study the economic condition of the United Kingdom. The results of his observations appeared in a tract, De l'Angleterre et des Anglais.

A third edition of the Traité appeared in 1817. A chair of industrial economy was established for him in 1819 at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers. Also in 1819, he was one of the founders of the École spéciale de commerce et d'industrie, which became the first business school in the world.[5] In 1831, he was made professor of political economy at the Collège de France. In 1828–1830, he published his Cours complet d'economie politique pratique. In 1826, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In his later years, Say became subject to attacks of nervous apoplexy. He lost his wife in January 1830 and from that time his health constantly declined.

When the revolution of that year broke out, he was named a member of the council-general of the department of the Seine, but found it necessary to resign.

Say died in Paris on 15 November 1832 and was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Say's law

He is well known for Say's law (or Say's law of markets), often summarised as such:

- "Aggregate supply creates its own aggregate demand"

- "Supply creates its own demand"

- "Supply constitutes its own demand"

- "If you build it, they will come"

- "Inherent in supply is the wherewithal for its own consumption" (direct translation from French Traité d'économie politique)

The exact phrase "supply creates its own demand" was coined by John Maynard Keynes, who criticized it, but this characterization is disputed as a misrepresentation by some advocates of Say's law.[6] Similar sentiments, though different wordings, appear in the work of John Stuart Mill (1848) and his father James Mill (1808). The Scottish classical economist James Mill restates Say's law in 1808, writing that "production of commodities creates, and is the one and universal cause which creates a market for the commodities produced".[7]

In Say's language, "products are paid for with products" (1803, p. 153) or "a glut can take place only when there are too many means of production applied to one kind of product and not enough to another" (1803, pp. 178–179). Explaining his point at length, he wrote the following:[8]

It is worthwhile to remark that a product is no sooner created than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value. When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product, he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should diminish in his hands. Nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable. But the only way of getting rid of money is in the purchase of some product or other. Thus the mere circumstance of creation of one product immediately opens a vent for other products. (J.B. Say, 1803: pp. 138–139)

He also wrote that it is not the abundance of money, but the abundance of other products in general that facilitates sales:[9]

Money performs but a momentary function in this double exchange; and when the transaction is finally closed, it will always be found, that one kind of commodity has been exchanged for another.

Say's law may also have been culled from Ecclesiastes 5:11 – "When goods increase, they are increased that eat them: and what good is there to the owners thereof, saving the beholding of them with their eyes?" (KJV). Say's law has been considered by John Kenneth Galbraith as "the most distinguished example of the stability of economic ideas, including when they are wrong".[10]

Quotes

- On taxes

"To encourage whale-hunting, the English government prohibits vegetable oils which we burn in France in draught-lamps. What results from this? That one of these lamps, which costs a Frenchmen 60 francs per year, costs an Englishman 150 francs. The intention, some say, is to support the navy and to multiply the number of sailors, that each lamp nozzle costs Englishmen 90 more francs than in France. In this case, it is to multiply the number of sailors by the means of a trade that generates losses: it would be better to multiply them by a lucrative trade."

"A hard working laborer, I was told, fancied working by candlelight. He had calculated that, during his vigil, he burned a 4-penny candle, earning 8 pennies by his work. A tax on tallows and another on the manufacture of the candles increased by 5 pennies the cost of his luminary, which became thus more expensive than the value of the product that it could shed light upon. From then on, as soon as night fell, the workman remained idle; he lost the 4 pennies which his work could obtain him, and without the tax service perceiving anything out of this production. Such a loss must be multiplied by the number of the workmen in a city and by the number of the days of the year."

- On property rights

"There is no security of property, where a despotic authority can possess itself of the property of the subject against his consent. Neither is there such security, where the consent is merely nominal and delusive."

"The property a man has in his own industry, is violated, whenever he is forbidden the free exercise of his faculties or talents, except insomuch as they would interfere with the rights of third parties."

— Jean-Baptiste Say, A Treatise on Political Economy, 1803

References

- ↑ William O. Thweatt, Early Formulators of Say's Law, in Wood, John Cunningham (editor); Kates, Steven (editor) (2000). Jean-Baptiste Say: Critical Assessments. V. London: Routledge. pp. 78–93.

- ↑ Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce: Civilisation and Capitalism 15th–18th Century, 1979:181

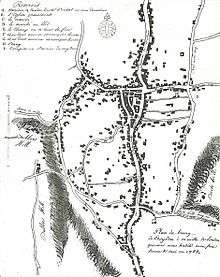

- ↑ Lancaster, Brian (March 2012), "Jean-Baptiste Say's 1785 Croydon street plan", Croydon Natural History & Scientific Society Bulletin, 144: 2–5

- ↑ Lancaster, Brian (2015). "Jean-Baptiste Say's First Visit to England (1785/6)". History of European Ideas. 41 (7): 922–930.

- ↑ Kaplan, Andreas (2014). "European management and European business schools: Insights from the history of business schools". European Management Journal. 32 (4): 529–534. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2014.03.006.

- ↑ (Clower 2004, p. 92)

- ↑ James Mill, Commerce Defended (1808), Chapter VI: Consumption, p. 81

- ↑ Information on Jean-Baptiste Say Archived 2009-03-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste Say: A treatise on political economy; or the production distribution and consumption of wealth. Translated from the fourth edition of the French. Batoche Books Kitchener 2001, p. 57

- ↑ Galbraith, John Kenneth (1975), Money: Whence It Came, Where It Went, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-19843-7 .

Further reading

- Hart, David (2008). "Say, Jean-Baptiste (1767–1832)". In Hamowy, Ronald. The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 449–50. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n274. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Hollander, Samuel (2005), Jean-Baptiste Say and the Classical Canon in Economics: the British Connection in French Classicism, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-32338-X .

- "Portrait: J.B. Say (1767–1832)". La nouvelle lettre, no 1064 (29 January 2011): 8.

- Schoorl, Evert (2012). Jean-Baptiste Say: Revolutionary, Entrepreneur, Economist. London: London. ISBN 9781135104108.

- Sowell, Thomas (1973), Say's Law: An Historical Analysis, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-04166-0 .

- Teilhac, Ernest (1927). L’oeuvre économique de Jean-Baptiste Say. Paris.

- Whatmore, Richard (2001), Republicanism and the French Revolution: An Intellectual History of Jean-Baptiste Say's Political Economy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924115-5 .

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jean-Baptiste Say |

- Works by or about Jean-Baptiste Say at Internet Archive

- Say's Law and Economic Growth

- Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832). The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Library of Economics and Liberty (2nd ed.). Liberty Fund. 2008.

- Nature of Things, by Jean-Baptiste Say. In Lalor's Cyclopedia at the Library of Economics and Liberty.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Economic Insights article (Volume 11, Number 1)

- A Treatise on Political Economy, by Jean-Baptiste Say at McMaster University Archive for the History of Economic Thought

- Letters to Malthus on Several Subjects of Political Economy (1821) at McMaster University Archive for the History of Economic Thought

- Jean-Baptiste Say at Find a Grave

- Jean-Baptiste Say at Goodreads