Mythology and commemorations of Benjamin Banneker

According to accounts that began to appear during the 1960s or earlier, a substantial mythology exaggerating Benjamin Banneker's accomplishments has developed during the two centuries that have elapsed since he lived (1731–1806).[1][2][3] Several such urban legends describe Banneker's alleged activities in the Washington, D.C. area around the time that he assisted Andrew Ellicott in the federal district boundary survey.[2][3][4][5][6][7] Others involve his clock, his almanacs and his journals.[2] Although parts of African-American culture, all lack support by historical evidence. Some are contradicted by such evidence.

A United States postage stamp and the names of a number of recreational and cultural facilities, schools, streets and other facilities and institutions throughout the United States have commemorated Banneker's documented and mythical accomplishments throughout the years since he lived.

Mythology of Benjamin Banneker

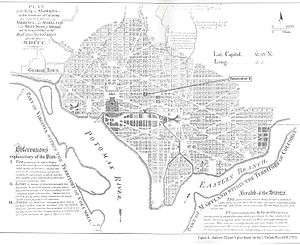

Plan of the City of Washington

While Andrew Ellicott and his team were conducting a survey of the boundaries of the future federal district during 1791-1792 (see Boundary Markers of the Original District of Columbia), Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant was preparing a plan for the federal capital city (the City of Washington) (see L'Enfant Plan). The capital city was to occupy a relatively small area bounded by the Potomac River, the Anacostia River (known at the time as the "Eastern Branch"), the base of the escarpment of the Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line, and Rock Creek at the center of the much larger 100-square-mile (260 km2) federal district (known at the time as the "Territory of Columbia") (see Founding of Washington, D.C.).[9][10][11][12] In late February 1792, President George Washington dismissed L'Enfant, who had failed to have his plan published and who was experiencing frequent conflicts with the three Commissioners that Washington had appointed to supervise the planning and survey of the federal district and city.[11][13][14]

A number of undocumented stories connecting Benjamin Banneker and L'Enfant's plan for the federal capital city have appeared over the years. In 1921, Daniel A. P. Murray, an African American serving as an assistant librarian of the Library of Congress, read a paper before the Banneker Association of Washington that stated:

... L'Enfant made a demand that could not be accorded and ... in a fit of high dudgeon gathered all his plans and papers and unceremoniously left. ... Washington was in despair, since it involved a defeat of all of his cherished plans in regard to the "Federal City." This perturbation on his part was quickly ended, however, when it transpired that Banneker had daily for the purposes of calculation and practice, transcribed nearly all L'Enfant's field notes and through the assistance they afforded Mr. Andrew Ellicott, L'Enfant's assistant, Washington City was laid down very nearly on the original lines. ... By this act the brain of the Afro-American is indissolubly linked with the Capital and nation.[15]

In 1976 (more than 50 years later), Jerome Klinkowitz stated within a book that described the works of Banneker and other early black American writers that Murray's report had initiated a myth about Banneker's career. Klinkowitz noted that Murray had not provided any support for his claim that Banneker had recalled L'Enfant's plan for Washington, D.C. Klinkowitz also described a number of other Banneker myths and subsequent works that had refuted them.[16]

By 1929, variations of the myth had become widespread. When describing the ceremonial presentation to Howard University in Washington, D.C., of a sundial memorializing Banneker, the Chicago Defender newspaper reported in that year that a speaker had stated that:

.... he (Banneker) was appointed by President George Washington to aid Major L'Enfant, famed French architect, to plan the layout of the District of Columbia. L'Enfant died before the work was completed, which required Banneker to carry on in his stead.[17]

However, as a book that won the 1917 Pulitzer Prize for History had earlier reported, L'Enfant lived long after he developed his plan for the federal capital city. He died near the City of Washington in 1825.[18]

In other versions of the legend, Banneker spent two days reconstructing the bulk of the city's plan from his presumably photographic memory after L'Enfant died or departed. In these versions, the plans that Banneker purportedly drew from memory provided the basis for the later construction of the federal capital city. Titles of works relating these versions of the fable have touted Banneker as "The Man Who Designed Washington", "The Man Who Saved Washington", "An Early American Hero", "Benjamin Banneker, Genius", and as one of the "100 Greatest African Americans".[19]

In another version of the tale, Banneker and Andrew Ellicott both surveyed the capital city's area and configured the final layout for the placement of major governmental buildings, boulevards and avenues while reconstructing L'Enfant's plan or on another occasion. According to this version, Banneker either "made astronomical calculations and implementations" that established points of significance within the city, including those of the "16th Street Meridian" (see White House meridian), the White House, the Capitol and the Treasury Building, or "helped in selecting the sites" of those features.[20]

A U.S. Treasury Department, Section of Fine Arts, mural in the Recorder of Deeds Building, which was constructed from 1940 to 1943 in Washington, D.C., perpetuates a Banneker legend by showing Banneker with a plan of the city of Washington.[21] The oil portrait was the winner of a juried competition that the Section held on behalf of Doctor William J. Thompkins, an African American political figure who was at the time serving as the Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia. The competition announcement stated that seven mural subjects had been “carefully worked out by the Recorder...following intensive research” to "reflect a phase of the contribution of the Negro to the American nation.” A mural on the subject of “Benjamin Banneker Surveys the District of Columbia” was to “show the presentation by Banneker and Mayor Ellicott, of the plans of the District of Columbia to the President, [and] Mr. Thomas Jefferson” in the presence of Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton.[22]

In 1976, an Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation historian told the following tale within a National Register of Historic Places nomination form for the "Benjamin Banneker: SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone (milestone) of the District of Columbia":

.... Major L'Enfant resigned his position before the planned design was completed. It was only through the efforts of Major Andrew Ellicott and Benjamin Banneker that the Federal City was completed.[23]

Citing a 1963 article in the Washington Star newspaper,[24] a 1990 documentation form related the following version of the story when supporting a listing in the National Register of Historic Places for twelve historic marker stones from the federal district boundary survey:

.... Fearing profiteering land speculators, L'Enfant would not allow anyone to see the plan. Ordered by the commissioners to reveal the plan, he instead left the United States, taking all copies of his plan for the District of Columbia with him. Banneker reproduced it from memory in minute detail, thereby allowing the work to continue.[25]

During a commemoration of Black History Month in February 1990, Congressman Roy Dyson of Maryland told the United States House of Representatives that Banneker had "helped to draw the plans for the District of Columbia".[26] Congressman Benjamin Gilman of New York stated during the same commemoration that Banneker had assisted in the layout of "our beautiful Capitol City".[27]

Documents published in 2003 and 2005 supporting the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. (including a report that a presidential commission planning the museum sent to the President and the Congress), later also connected Banneker with L'Enfant's plan of the city of Washington.[28][29] When the museum opened on the National Mall in September 2016, an exhibit entitled "The Founding of America" further perpetuated the legend when displaying a statue of Banneker holding a small telescope while standing in front of a plan of that city.[30] A National Park Service web page subsequently stated in 2018 that Banneker had "surveyed the city of Washington with Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant".[31]

However, historical research has shown that none of these legends can be correct.[3][4][32] As a researcher reported in 1969, Ellicott's 1791 assignment was to produce a survey of a square, the length of whose sides would each be 10 miles (16.1 km) (a "ten mile square").[9] L'Enfant was to survey, design and lay out the national capital city within this square.[9][33] Ellicott and L'Enfant each worked independently under the supervision of the three Commissioners that President Washington had earlier appointed.[9] Ellicott employed Banneker directly.[9] The researcher could find no evidence that Banneker ever worked with or for L'Enfant.[9]

Banneker left the federal capital area and returned to his home near Ellicott's Mills in April 1791.[4][7][34] At that time, L'Enfant was still developing his plan for the federal city and had not yet been dismissed from his job.[4] L'Enfant presented his plans to President Washington in June and August 1791, two and four months after Banneker had left.[4][7][35][36][37][38]

Further, there never was any need to reconstruct L'Enfant's plan. After completing the initial phases of the district boundary survey, Andrew Ellicott began to survey the federal city to help L'Enfant develop the city's plan.[39] During a contentious period in February 1792, Ellicott informed the Commissioners that L'Enfant had refused to give him an original plan that L'Enfant possessed at the time.[40][41]

Ellicott stated in his letters that, although he was refused the original plan, he was familiar with L'Enfant's system and had many notes of the surveys that he had made himself.[42] Additionally, L' Enfant had earlier given to Washington at least two versions of his plan, one of which Washington had sent to Congress in December 1791.[35][36][43]

Andrew Ellicott, with the aid of his brother, Benjamin Ellicott, then revised L'Enfant's plan, despite L'Enfant's protests.[6][40][44] Shortly thereafter, Washington dismissed L'Enfant.[6][40][44]

After L'Enfant departed, the Commissioners assigned Ellicott the dual responsibility for continuing L'Enfant's work on the design of the city and the layout of public buildings, streets and property lots, in addition to completing the boundary survey.[9] Andrew Ellicott therefore continued the city survey in accordance with the revised plan that he and his brother had prepared.[13][35][40][44][45][46]

There is no historical evidence that shows that Banneker was involved in any of this.[3][6] Six months before Ellicott revised L'Enfant's plan, Banneker sent a letter to Thomas Jefferson from "Maryland, Baltimore County, near Ellicotts Lower Mills" that he dated as "Augt. 19th: 1791", in which he described the time that he had earlier spent "at the Federal Territory by the request of Mr. Andrew Ellicott".[47] As a researcher has reported, the letter that Ellicott addressed to the Commissioners in February 1792 describing his revision of L'Enfant's plan did not mention Banneker's name.[48] Jefferson did not describe any connection between Banneker and the plan for the federal city when relating his knowledge of Banneker's works in a letter that he sent to Joel Barlow in 1809, three years after Banneker's death.[49]

L'Enfant did not leave the United States after ending his work on the federal capital city's plan. Soon afterwards, he began to plan the city of Paterson, New Jersey.[50] The United States Congress acknowledged the work that he had performed when preparing his plan for the city of Washington by voting to pay him for his efforts.[51]

In 1887, the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey created and distributed a facsimile of a manuscript plan for the future City of Washington. The plan contains in the last line of an oval in its upper left hand corner the words "By Peter Charles L'Enfant" (L'Enfant's adopted name).[8] A 1914 book describing the history of the City of Washington reported that L'Enfant's plan contained a title legend that identified L'Enfant as the plan's author.[52]

A 1902 report of a committee of the United States Senate (the McMillan Plan), an inlay of a city plan in a Washington, D.C., plaza constructed in 1980 (Freedom Plaza), and at least one book relating the history of the District of Columbia contain copies of the portion of a plan for the federal capital city that contains the oval that bears L'Enfant's name.[10][53][a 1] The U.S. Library of Congress now holds in its collections a manuscript of a plan for the federal city that contains that oval.[54] As an original version of L'Enfant's plan still exists, President Washington and Ellicott clearly had at least one such version available for their use when L'Enfant departed.

In November 1971, the National Park Service held a public ceremony to dedicate and name Benjamin Banneker Park on L'Enfant Promenade in Washington, D.C.[55][56] The U.S. Department of Interior authorized the naming as an official commemorative designation celebrating Banneker's role in the survey and design of the nation’s capital.[55] Speakers at the event hailed Banneker for his contributions to the plan of the capital city after L'Enfant's dismissal, claiming that Banneker had saved the plan by reconstructing it from memory.[56] A researcher later pointed out that these statements were erroneous.[56]

During a 1997 ceremony that again commemorated Banneker while rededicating the park, speakers stated that Banneker had surveyed the original City of Washington.[57] However, research reported more than two decades earlier had found that such statements lacked supporting evidence and appeared to be incorrect.[3]

In May 2000, Austin H. Kiplinger and Walter E. Washington, the co-chairmen of the Leadership Committee for the planned City Museum of Washington, D.C., wrote in The Washington Post that the museum would remind visitors that Banneker had helped complete L'Enfant's project to map the city.[58] A letter to the editor of the Post entitled "District History Lesson" then responded to this statement by noting that Andrew Ellicott was the person who revised L'Enfant's plan and who completed the capital city's mapping, and that Banneker had played no part in this.[59]

Appointment to planning commission for Washington, D.C.

In 1918, Henry E. Baker, an African American serving as an assistant examiner in the United States Patent Office, wrote of Banneker in The Journal of Negro History (now titled The Journal of African American History): "It is on record that it was on the suggestion of his friend, Major Andrew Ellicott, ..., that Thomas Jefferson nominated Banneker and Washington appointed him a member of the commission..." whose duties were to "define the boundary line and lay out the streets of the Federal Territory, later called the District of Columbia".[60] However, Baker did not identify the record on which he based this statement. Baker additionally stated that Andrew Ellicott and L'Enfant were also members of this commission.

In 2000, historians John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., wrote in the eighth edition of the book, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, whose first edition had been published in 1947, that the "most distinguished honor that Banneker received was his appointment to serve with the commission to define the boundary lines and lay out the streets of the District of Columbia." The writers, who referenced Baker's 1918 article, also stated that Banneker's friend, George Ellicott (Andrew Ellicott's cousin), was a member of the commission and that Thomas Jefferson had submitted Banneker's name to President Washington.[61]

In 2005, actor James Avery narrated a DVD entitled A History of Black Achievement in America. A quiz based on a section of the DVD entitled "Emergence of the Black Hero" asked:

Benjamin Banneker was a member of the planning commission for ____________ .

a. New York City

b. Philadelphia

c. Washington, D.C.

d. Atlanta[62]

However, historical evidence contradicts the statements that Baker, Franklin and Moss made and suggests that the question in the quiz has no correct answer. In 1791, President Washington appointed Thomas Johnson, Daniel Carroll and David Stuart to be the three commissioners who, in accordance with the authority that the federal Residence Act of 1790 had granted to the President, would oversee the survey of the federal district, and "according to such Plans, as the President shall approve", provide public buildings to accommodate the federal government in 1800.[63][64][65]

The Residence Act did not authorize the President to appoint any more than three commissioners that could serve at the same time.[66] As Banneker, Andrew Ellicott, and L'Enfant performed their tasks during the time that Johnson, Carroll and Stuart were serving as commissioners, President Washington could not have legally appointed either Banneker, Ellicott or L'Enfant to serve as members of the "commission" that Baker, Franklin and Moss described.

Further, Franklin and Moss did not cite any documentation to support their contention that George Ellicott participated in the planning and design of the nation's capital. Andrew (not George) Ellicott led the survey that defined the District's boundary lines and, with L'Enfant, laid out the capital city's streets. Additionally, there is no historical evidence that shows that President Washington participated in the process that resulted in Banneker's appointment as an assistant to Andrew Ellicott on the District boundary survey team.[67]

In 1999, a researcher reported that an exhaustive survey of U.S. government repositories, including the Public Buildings and Grounds files in the National Archives and collections in the Library of Congress, had failed to identify Banneker's name on any contemporary documents or records relating to the selection, planning and survey of the City of Washington. The researcher also noted that none of L'Enfant's survey papers that the researcher had found had contained Banneker's name.[68] Another researcher has been unable to find any documentation that shows that Washington and Banneker ever met.[69]

Boundary markers of the District of Columbia

During 1791 and 1792, a survey team that Andrew Ellicott led placed forty mile marker stones along the 10 miles (16.1 km)-long sides of a square that would form the boundaries of the future District of Columbia. Ellicott's survey began at the square's south corner at Jones Point in Alexandria, Virginia (see Boundary Markers of the Original District of Columbia).[11][70] Several accounts of the marker stones incorrectly attribute their placement to Banneker.

In 1994, historians preparing a National Register of Historic Places registration form for the L'Enfant plan of the City of Washington wrote that forty boundary stones laid at one-mile intervals had established the District's boundaries based on Banneker's celestial calculations.[71] In 2005, a data gathering report for the planned Smithsonian Museum of African American History in Washington, D.C., stated that Banneker had assisted Andrew Ellicott in laying out the forty boundary marker stones.[72]

In 2012, Penny Carr, a regent of the Falls Church, Virginia, chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) wrote in an online community newspaper that Andrew Ellicott and Banneker had in 1791 put in place the westernmost boundary marker stone of the original D.C. boundary. Carr stated that the marker now sits on the boundary line of Falls Church City, Fairfax County, and Arlington County.[73] Carr did not provide the source of this information.

A book published in May 2014 entitled "A History Lover's Guide to Washington" stated that both Ellicott and Banneker had "carefully placed the forty original boundary stones along the Washington, D.C. borders with Virginia and Maryland in 1791-1792".[74] Similary, on May 8, 2015, a Washington Post article describing a rededication ceremony for one of the marker stones reported that Sharon K. Thorne-Sulima, a regent of a chapter of the District of Columbia DAR, had said:

These stones are our nation’s oldest national landmarks that were placed by Andrew Ellicott and Benjamin Banneker. They officially laid the seat of government of our new nation.[75]

On May 30, 2015, a web version of a follow-up article in the Post carried the headline "Stones laid by Benjamin Banneker in the 1790s are still standing".[76] Disputing the headline's information, a June 1, 2015, comment following the article stated while citing an extensively referenced source[77] that Banneker had, "according to legend", made the astronomical observations and calculations needed to establish the location of the south corner of the District's square, but had not participated in any later parts of the square's survey.[78] (A 1974 publication had earlier pointed out that there was no evidence that Banneker had anything to do with the survey of the Federal City or with the final establishment of the boundaries of the Federal District.[3] Banneker apparently left the federal capital area and returned to his home at Ellicott's Mills in late April 1791, shortly after the south cornerstone was set in place during an April 15, 1791, ceremony.[79]) Nevertheless, in 2016, Charlie Clark, a columnist writing in a Falls Church newspaper, stated that Banneker had placed a District boundary stone in Clark's Arlington County, Virginia, neighborhood.[80]

A 2016 booklet that the government of Arlington County, Virginia, published to promote the County's African American history stated, "On April 15, 1791, officials dedicated the first boundary stone based on Banneker's calculations."[81] However, it was actually a March 30, 1791, presidential proclamation by George Washington that established "Jones's point, the upper cape of Hunting Creek in Virginia" as the starting point for the federal district's boundary survey.[82] Washington did not need any calculations to determine the location of Jones Point. Further, according to an April 21, 1791, news report of the dedication ceremony for the first boundary stone (the south cornerstone), it was Andrew Ellicott who ″ascertained the precise point from which the first line of the district was to proceed". The news report did not mention Banneker's name.[83]

A National Park Service web page entitled Benjamin Banneker and the Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia stated in 2018:

Along with a team, Banneker identified the boundaries of the capitol city. They installed intermittent stone markers along the perimeter of the District.[31]

The Park Service did not provide a source for this statement.

Banneker's clock

In 1865, an American abolitionist, Lydia Maria Child, authored a book intended to be used to teach recently freed African Americans to read and to provide them with inspiration.[84] Her book stated that Banneker had constructed "the first clock ever made in this country".[85]

In 1902, an African American professor of mathematics at Howard University, Kelly Miller, made a similar statement in a United States Bureau of Education publication, claiming that Banneker had in 1770 "constructed a clock to strike the hours, the first to be made in America".[86] In contrast, Philip Lee Phillips, a Library of Congress librarian,[87] more cautiously stated in a 1916 paper read before the Columbia Historical Society in Washington, D.C. that Banneker "is said to have made, entirely with his own hand, a clock of which it is said every portion was made in America."[88]

In 1980, the United States Postal Service (USPS) issued a postage stamp that commemorated Banneker. The USPS' description of Banneker stated: "... In 1753, he built the first watch made in America."[89] A 2004 USPS pamphlet illustrating the stamp stated that Banneker "constructed the first wooden striking clock made in America."[90] The website of the Banneker-Douglass Museum, the State of Maryland's official museum of African American heritage, similarly claimed in 2015 that Banneker crafted "the first wooden striking clock in America".[91]

In 1987, Oregon's Portland Public Schools District published a series of educational materials entitled African-American Baseline Essays. The Essays were to be "used by teachers and other District staff as a reference and resource just as adopted textbooks and other resources are used" as part of "a huge multicultural curriculum-development effort."[92] An Essay entitled African-American Contributions to Science and Technology stated that Banneker had "made America's first clock".[93] Noting in 1994 that the Essays "are the most widespread Afrocentric teaching material", a critic writing for the Washington Post cited the Essays' "crippling flaws". The specified flaws included several Banneker stories that a researcher had refuted more than a decade before the Essays appeared.[94]

When supporting the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African American History and Culture, a 2004 report to the President of the United States and the United States Congress stated that Banneker was an African American inventor.[28] In 2015, columnists Al Kamen and Colby Itkowitz repeated that statement in a Washington Post article.[95] A National Park Service web page, which also claimed that Banneker was an inventor, stated in 2018 that he had "constructed one of the first entirely wooden clocks in America."[31]

However, while several 19th, 20th and 21st century biographers have written that Banneker constructed a clock, none of these alleged that Banneker invented a timepiece or anything else. None stated that Banneker's clock had any characteristics that earlier American clocks had lacked.[96] One reported in 1999 that several watch and clockmakers had been active in Maryland before Banneker constructed his clock and that there were at least four such craftsmen in Annapolis alone prior to 1750.[97] The only accounts of the clock by people who had observed it reported only that it was made of wood, that it was suspended in a corner of Banneker's log cabin, that it had struck the hour and that Banneker had stated that its only model was a borrowed watch.[98]

Documents describing the history of clockmaking in America show that Banneker's clock was not the first of its kind made in America. Connecticut clockmakers were crafting striking clocks throughout the 1600s, before Banneker was born.[99] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City holds in its collections a striking clock that Benjamin Bagnall constructed in Boston before 1740 (when Banneker was 9 years old) and that Elisha Williams probably acquired between 1725 and 1739 while he was rector of Yale College.[100]

There is some evidence that wooden clocks were being made as early as 1715 near New Haven, Connecticut.[99][101] Benjamin Cheney of East Hartford, Connecticut, was producing wooden striking clocks by 1745, eight years before Banneker completed his own wooden striking clock in 1753.[99][101][102][103]

Banneker's almanacs

In addition to incorrectly describing Banneker's clock, Lydia Maria Child's 1865 book stated that Banneker's almanac was the first ever made in America.[104] After also incorrectly describing the clock, Kelly Miller's 1902 publication similarly stated that Banneker's 1792 almanac for Pennsylvania, Virginia and Maryland was "the first almanac constructed in America".[86]

A National Register of Historic Places nomination form for the ″Benjamin Banneker: SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone (milestone) of the District of Columbia" that an Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation historian prepared in 1976 states that Banneker's astronomical calculations "led to his writing one of the first series of almanacs printed in the United States."[105] A National Park Service web page repeated that statement in 2018.[31]

However, William Pierce's An Almanac Calculated for New England, printed in 1639 by Stephen Day in Cambridge, Massachusetts, preceded Banneker's birth by nearly a century.[106] Nathaniel Ames issued his Astronomical Diary and Almanack in Massachusetts in 1725 and annually after c.1732.[107] James Franklin published The Rhode Island Almanack by "Poor Robin" for each year from 1728 to 1735.[108] James' brother, Benjamin Franklin, published his annual Poor Richard's Almanack in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1732 to 1758, more than thirty years before Banneker wrote his own first almanac in 1791.[109] A decade before printers published Banneker's first almanac, Andrew Ellicott began to publish a series of almanacs, The United States Almanack, the earliest known copy of which bears the date of 1782.[110]

Astronomical works

An announcement describing an astronomical sciences program that the "Banneker Institute" posted on Harvard University's website in 2016 stated: "As a forefather to Black American contributions to science, his (Banneker's) eminence has earned him the distinction of being the first professional astronomer in America." The announcement did not provide the source of this information.[111]

Banneker prepared his first published almanac in 1791, during the same year that he participated in the federal district boundary survey.[112][113] As a 1942 journal article entitled "Early American Astronomy" has reported, American almanacs published as early as 1687 predicted eclipses and other astronomical events, while John Winthrop, David Rittenhouse and other Americans authored publications that described their telescopic observations of the 1761 and 1769 transits of Venus soon after these events occurred (See also: Colonial American Astronomy).[114][115] In contrast to the statement in the Banneker Institute's posting, that article and others that have reported the works of 17th and 18th century American astronomers either do not mention Banneker's name or describe his works as occurring after those of other Americans.[114][116]

A book relating the history of American astronomy stated, that as a result of the American Revolution, "... what astronomical activity there was from 1776 through 1830 was sporadic and inconsequential".[117] Another such book has stated that "the dawn of American professional astronomy" began in the middle of the 19th century.[118]

Seventeen-year cicada

In 2004, during a year in which Brood X of the seventeen-year periodical cicada (Magicicada septendecim) emerged from the ground in large numbers, columnist Courtland Milloy wrote in The Washington Post an article entitled "Time to Create Some Buzz for Banneker".[119] Milloy claimed that Banneker "is believed to have been the first person to document this noisy recurrence" of the insect. Milloy stated that Banneker had recorded in a journal "published around 1800" that the "locusts" had appeared in 1749, 1766 and 1783.

Milloy further noted that Banneker had predicted that the insects would return in 1800.[120] In 2014, the authors of an online publication that reproduced Banneker's handwritten journal report cited Milloy's article and contended that "Banneker was one of the first naturalists to record scientific information and observations of the seventeen-year cicada".[121]

However, earlier published accounts of the periodical cicada's life cycle describe the history of cicada sightings differently. These accounts cite descriptions of fifteen- to seventeen-year recurrences of enormous numbers of noisy emergent cicadas that people had written as early as 1733,[122][123] when Banneker was two years old.

Pehr Kalm, a Swedish naturalist visiting Pennsylvania and New Jersey in 1749 on behalf of his nation's government, observed in late May the first of the three Brood X emergences that Banneker's journal later documented.[122][124] When reporting the event in a paper that a Swedish academic journal published in 1756, Kalm wrote:

The general opinion is that these insects appear in these fantastic numbers in every seventeenth year. Meanwhile, except for an occasional one which may appear in the summer, they remain underground.

There is considerable evidence that these insects appear every seventeenth year in Pennsylvania.[124]

Kalm then described documents (including one that he had obtained from Benjamin Franklin) that had recorded in Pennsylvania the emergence from the ground of large numbers of cicadas during May 1715 and May 1732. He noted that the people who had prepared these documents had made no such reports in other years.[124] Kalm further noted that others had informed him that they had seen cicadas only occasionally before the insects appeared in large swarms during 1749.[124] He additionally stated that he had not heard any cicadas in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in 1750 in the same months and areas in which he had heard many in 1749.[124] The 1715 and 1732 reports, when coupled with his own 1749 and 1750 observations, supported the previous "general opinion" that he had cited.

Kalm summarized his findings in a paper translated into English in 1771,[125] stating:

There are a kind of Locusts which about every seventeen years come hither in incredible numbers .... In the interval between the years when they are so numerous, they are only seen or heard single in the woods.[122][126]

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus gave to the insect that Kalm had described the Latin name of Cicada septendecim (seventeen-year cicada) in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[127] Banneker's second observation of a Brood X emergence occurred eight years later. A writer documented that emergence in a 1766 journal article entitled Observations on the cicada, or locust of America, which appears periodically once in 16 or 17 years.[128]

Other legends and embellishments

In 1930, writer Lloyd Morris claimed in an academic journal article entitled The Negro "Renaissance" that "Benjamin Banneker attracted the attention of a President.... President Thomas Jefferson sent a copy of one of Banneker's almanacs to his friend, the French philosopher Condorcet....".[129] However, Thomas Jefferson sent Banneker's almanac to the Marquis de Condorcet in 1791, a decade before he became President in 1801.[130][131]

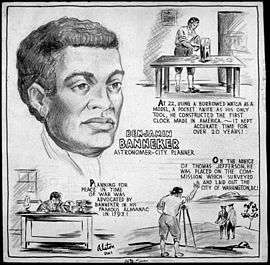

In 1943, an African American artist, Charles Alston, who was at the time an employee of the United States Office of War Information, designed a cartoon that embellished the statements that Henry E. Baker had made in 1918.[60] Like Baker, Alston incorrectly claimed that Banneker "was placed on the commission which surveyed and laid out the city of Washington, D.C." Alston extended this claim by also stating that Banneker had been a "city planner". Alston's cartoon additionally repeated a claim that Lydia Maria Child had made in 1865[85] by stating that Banneker had "constructed the first clock made in America".[132]

In 1976, the singer-songwriter Stevie Wonder celebrated Banneker's mythical feats in his song "Black Man", from the album Songs in the Key of Life. The lyrics of the song state:

Who was the man who helped design the nation's capitol, Made the first clock to give time in America and wrote the first almanac? Benjamin Banneker, a black man[133]

The question's answer is incorrect. Banneker did not help design either the U.S. Capitol or the nation's capital city and did not write America's first almanac.[7] The first known clockmaker of record in America was Thomas Nash, an early settler of New Haven in 1638.[99]

In 1998, a Catalan writer, Núria Perpinyà, created a fictional character, Aleph Banneker, in her novel Un bon error (A Good Mistake). The writer's website reported that the character, an "eminent scientist", was meant to recall Benjamin Banneker, an eighteenth-century "black astronomer and urbanist".[134] However, none of Banneker's documented activities or writings suggest that he was an "urbanist".[135]

In 1999, the National Capital Memorial Commission concluded that the relationship between Banneker and L’Enfant was such that L’Enfant Promenade was the most logical place in Washington, DC on which to construct a proposed memorial to Banneker.[136] However, a researcher has been unable find any historical evidence that shows that Banneker had any relationship at all to L'Enfant or to L'Enfant's plan for the city, although he wrote that the two men "undoubtedly" met each other after L'Enfant arrived in Georgetown in March 1791 to begin his work.[56][68][137]

A history painting by Peter Waddell entitled A Vision Unfolds debuted in 2005 within an exhibition on Freemasonry that the Octagon House's museum in Washington, D.C., was hosting. The oil painting was again displayed in 2007, 2009, 2010 and 2011, first in the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska and later in the National Heritage Museum in Lexington, Massachusetts and in the Scottish Rite Center of the District of Columbia in Washington, D.C.[138] Waddell's painting contains elements present in Edward Savage's 1789-1796 painting The Washington Family, which portrays President George Washington and his wife Martha viewing a plan of the City of Washington.[139]

A Vision Unfolds depicts a meeting that is taking place within an elaborate surveying tent. In the imaginary scene, Banneker presents a map of the federal district (the Territory of Columbia) to President Washington and Andrew Ellicott.[138][140]

However, Andrew Ellicott completed his survey of the federal district's boundaries in 1792.[9][11] On January 1, 1793, Ellicott submitted to the three commissioners "a report of his first map of the four lines of experiment, showing a half mile on each side, including the district of territory, with a survey of the different waters within the territory".[141] The Library of Congress has attributed to 1793 Ellicott's earliest map of the Territory of Columbia that the Library holds within its collections.[140] As Banneker left the federal capital area in 1791,[3][4][34] Banneker could not have had any association with the map that Waddell depicted.

Further, writers have pointed out that there is no evidence that Banneker had anything to do with the final establishment of the federal district's boundaries.[3] Additionally, a researcher has been unable to find any documentation that shows that President Washington and Banneker ever met.[69]

In 2018, a National Park Service web page stated that "Banneker became one of the first black civil servants of the new nation" when "he surveyed the city of Washington".[31] However, a researcher had reported more than 40 years earlier that it was Andrew Ellicott (not the federal government) who hired Banneker to participate in the survey of the federal district.[9] Ellicott paid Banneker $60 for his participation, including travel expenses.[142]

Commemorative U.S. quarter dollar coin nomination

In 2008, the District of Columbia government considered selecting an image of Banneker for the reverse side of the District of Columbia quarter in the 2009 District of Columbia and United States Territories Quarter Program.[143] The original narrative supporting this selection[144] (subsequently revised)[145] alleged that Banneker helped design the new capital city, was an inventor, was "among the first ever African-American presidential appointees" and was "a founder of Washington, D.C."

After the District chose to commemorate another person on the coin, the District's mayor, Adrian M. Fenty, sent a letter to the Director of the United States Mint, Edmund C. Moy, that claimed that Banneker "played an integral role in the physical design of the nation's capital."[146] However, there are no known documents that show that any president ever appointed Banneker to any position or that Banneker ever invented anything. Further, Banneker played no role at all in the design, development or founding of the nation's capital beyond his three-month participation in the two-year survey of the federal district's boundaries.[3][49][142]

Historical markers

Several historical markers in Maryland and Washington, D.C., contain information relating to Benjamin Banneker that is unsupported by historical evidence or is contradicted by such evidence:

Historical marker in Benjamin Banneker Historical Park, Baltimore County, Maryland

A commemorative historical marker that the Maryland Historical Society erected on the present grounds of Benjamin Banneker Historical Park in Baltimore County, Maryland, states that Banneker "published the first Maryland almanac" in 1792.[147] A researcher has reported that this statement is incorrect.[148] The researcher stated that Banneker modeled the format of his almanac after a series of almanacs (The United States Almanack) that Andrew Ellicott had authored from 1781 to 1785.[110] Ellicott had lived in Maryland during some of those years.[110] Ellicott's almanacs were published in Baltimore, Maryland.[149]

Further, Banneker did not "publish" his 1792 almanac. Although he authored this work, others printed, distributed and sold it.[112]

Historical marker in Benjamin Banneker Park, Washington, DC

A historical marker that the National Park Service erected in Benjamin Banneker Park in Washington, D.C., in 1997[150][a 2] states in an unreferenced paragraph:

Banneker became intrigued by a pocket watch he had seen as a young man. Using a knife he intricately carved out the wheels and gears of a wooden timepiece. The remarkable clock he constructed from memory kept time and struck the hours for the next fifty years.[151]

However, Banneker completed his clock at the age of 22, when he was still a young man.[103][152] No historical evidence shows that he constructed the clock from memory.[153]

Further, it is open to question as to whether the clock was actually "remarkable". A researcher has noted that at least four clockmakers were working in Annapolis, Maryland, before 1753, when Banneker completed his own clock.[97]

A photograph on the historical marker illustrates a wooden striking clock that Benjamin Cheney constructed around 1760.[151][154] The marker does not indicate that the clock is not Banneker's.[151]

Historical marker in Newseum, Washington, DC

In 2008, when the Newseum opened to the public on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., visitors looking over the Avenue could read a historical marker that stated:

Benjamin Banneker assisted Chief Surveyor Andrew Ellicott in laying out the Avenue based on Pierre L’Enfant’s Plan. President George Washington appointed Ellicott and Banneker to survey the boundaries of the new city.[155]

Little or none of this appears to be correct. Banneker had no documented involvement with the laying out of Pennsylvania Avenue or with L’Enfant’s Plan.[3][4][7] Andrew Ellicott surveyed the boundaries of the federal district (not the “boundaries of the new city”) at the suggestion of Thomas Jefferson.[64] Ellicott (not Washington) appointed Banneker to assist in the boundary survey.[9][67]

Commemorations of Benjamin Banneker

A United States postage stamp and the names of a number of recreational and cultural facilities, educational institutions, streets and other facilities and institutions throughout the United States have commemorated Banneker's documented and mythical accomplishments throughout the years since he lived.

Benjamin Banneker postage stamp

On February 15, 1980, during Black History Month, the United States Postal Service issued in Annapolis, Maryland, a 15 cent commemorative postage stamp that featured a portrait of Banneker.[89][90][156][157] An image of Banneker standing behind a short telescope mounted on a tripod was superimposed upon the portrait.[158] The device shown in the stamp resembles Andrew Ellicott's transit and equal altitude instrument (see Theodolite), which is presently in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.[159]

The stamp was the third in the Postal Service's Black Heritage stamp series.[156][160] The featured portrait was one that Jerry Pinkney of Croton-on-Hudson, New York, who designed the first nine stamps in the series, had earlier placed on another approved version of the stamp.[161] A Banneker biographer subsequently noted that, because no known portrait of Banneker exists, the stamp artist had based the portrait on "imagined features".[162]

Recreational and cultural facilities

The names of a number of recreational and cultural facilities commemorate Banneker. These facilities include parks, playgrounds, community centers, museums and a planetarium.

Parks

Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum, Baltimore County, Maryland

A park commemorating Benjamin Banneker is located in a stream valley woodland at the former site of Banneker's farm and residence in Oella, Maryland, between Ellicott City and the City of Baltimore.[163][164][a 3] The Baltimore County Department of Recreation and Parks manages the $2.5 million facility, which was dedicated on June 9, 1998.[165] The park, which encompasses 138 acres (56 ha) and contains archaeological sites and extensive nature trails, is the largest original African American historical site in the United States.[166] The primary focus of the park is a museum highlighting Banneker's contributions.[a 4] The museum contains a visitors center that features a collection of Banneker's works and artifacts, a community gallery, a gift shop and a patio garden.[166][167]

The park contains an 1850s stone farmhouse, now named the "Molly Banneky House". The three-story house was restored as an office complex in 2004.[168][a 5]

On November 12, 2009, officials opened a 224 square feet (20.8 m2) replica of Banneker's log cabin on the park grounds, reportedly two days before the 278th anniversary of Banneker's birth.[169][170][a 6] Baltimore County's delegation to the Maryland General Assembly secured a $400,000 state bond for the design and construction of the cabin.[169][171] The original estimated cost to construct the cabin in accordance with its drawings and specifications was $240,700.[172]

A historical marker that the Maryland Historical Society erected to commemorate Banneker stands on the grounds of the park.[147] The marker replaced the last of three earlier markers that vandals had previously destroyed.[173]

Benjamin Banneker Park and Memorial, Washington, D.C.

A 4.7 acres (1.9 ha) urban park memorializing Benjamin Banneker is located in southwest Washington, D.C., one half mile (800 m) south of the Smithsonian Institution's "Castle" on the National Mall. The park features a prominent overlook at the south end of L'Enfant Promenade and Tenth Street SW. A traffic circle, named Banneker Circle SW, surrounds the overlook. A grassy slope descends steeply from the traffic circle to the Southwest Freeway (Interstate 395), Ninth Street SW and Maine Avenue SW.[55][174][175][a 7]

The National Park Service (NPS) operates the park as part of its National Mall and Memorial Parks administrative unit.[176] The NPS erected a historical marker near the park's entrance in 1997.[150][151][174][175][177][178] The park is now at stop number 8 on Washington's Southwest Heritage Trail.[179]

In 1967, landscape architect Daniel Urban Kiley completed the design of the "Tenth Street Overlook".[150] After the District of Columbia Redevelopment Land Agency completed construction of the Overlook in 1969, the Agency transferred the Overlook to the NPS in 1970.[150]

The elliptical 200 feet (61 m) wide overlook provides elevated views of the nearby Southwest Waterfront, Washington Channel, East Potomac Park, Potomac River and more distant areas. The centerpiece of the overlook's modernist plaza is a large conical fountain that projects water more than 30 feet in the air and catches it in a circular basin made from honed green granite. The rings of the fountain and basin in the center of the site are reiterated in the benches, double rows of London Plane trees, and low concrete walls that establish the plaza’s edge. The ground plane is paved with granite squares, a continuation of L'Enfant Promenade's materials. The ground plane is concave, and with the trees and fountain helps define the spatial volume of the plaza.[175][180]

In 1970, the District of Columbia City Council passed a resolution that petitioned the NPS to rename the Overlook as Banneker Park, arguing that the Council had already renamed the adjacent highway circle as Banneker Circle, S.W.[150] The NPS thereupon hosted a dedication ceremony in 1971 that renamed the Overlook as "Benjamin Banneker Park".[150] Following completion of a restoration project, the park was ceremoniously rededicated in 1997 to again commemorate Banneker.[150][181] However, a 2016 NPS publication later noted that the NPS had renamed the Overlook to commemorate Banneker even though the area had no specific connection to Banneker himself.[182]

In 1998, the 105th United States Congress enacted legislation that authorized the Washington Interdependence Council of the District of Columbia to establish at the Council's expense a memorial on federal land in the District that would commemorate Banneker's accomplishments.[136][183] The Council plans to erect this memorial in or near the park.[136][184] In 2006, the Council held a charrette to select the artist that would design the memorial.[185]

Construction of the memorial was expected to begin after the United States Commission of Fine Arts and the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) approved the memorial's design and location in accordance with the legislation that authorized the establishment of the memorial and with the United States Code (40 U.S.C. § 8905).[184][186] However, the proposed memorial had by 1999 become a $17 million project that would contain a visitors' center near the "Castle" at the north end of the Promenade, a clock atop a tall pedestal at the midpoint of the Promenade, a statue of Banneker in the park's circle at the south end of the Promenade and a skyway over Interstate 395 that would connect the park to the waterfront.[150][187][188] After considering the proposal, the National Capital Memorial Commission rejected the placement of the statue in the park and decided to consult with the District of Columbia government about placing a Banneker memorial at the midpoint of the Promenade.[136][150][188][189]

The legislative authority relative to locating the Memorial on federal land lapsed in 2005.[150][189] This did not preclude the location of the memorial on lands such as the road right-of-way in the Promenade that are under the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia's government.[95][136][178][189]

During the 2000s, various organizations proposed to develop at the site of Benjamin Banneker Park a number of large facilities including a baseball stadium (later constructed elsewhere in D.C. as Nationals Park), the National Museum of African American History and Culture, a National Children's Museum and a National Museum of the American Latino.[189] In 2004, the D.C. Preservation League listed the Park as one of the most endangered places in the District because of such proposals to redevelop the park's area.[190] The League stated that the park, "Designed by renowned landscape architect Daniel Urban Kiley ... is culturally significant as the first public space in Washington named for an African American and is usually included in Black History tours".[190]

In 2006, the District government and the Federal Highway Administration issued an environmental assessment for "improvements" to the promenade and park that described a number of projects that could redevelop the area containing the park.[191] In 2011, a proposal surfaced that would erect a structure housing a "National Museum of the American People" at or near the site of the park.[192]

In 2012, the United States Army Corps of Engineers determined that Benjamin Banneker Park was not eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.[193] However, the District of Columbia State Historic Preservation Office (DC SHPO) did not concur with this determination.[193] The DC SHPO stated that additional research and coordination with the NPS would be needed before it could make a final determination of eligibility.[193] In 2014, the DC SHPO concurred with the superintendent of the National Mall and Memorial Parks that the park was eligible for inclusion in the National Register as an integral component of the 10th Street Promenade/Banneker Overlook composition, but not as an independent entity.[193]

In January 2013, the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) accepted "The SW Ecodistrict Plan" (see: Southwest Ecodistrict).[194] The Plan recommended the redesign of Benjamin Banneker Park and adjacent areas to accommodate one or more new memorials, museums and/or landscaping.[195]

in 2013, the NPS issued a "Cultural Landscapes Inventory" report for the park. The report described the features, significance and history of the park and its surrounding area, as well the planning processes that had influenced the park's construction and development.[196]

In September 2014, the NCPC accepted an addendum to the SW Ecodistrict Plan.[197] The addendum stated: "A modern, terraced landscape at Banneker Park is envisioned to enhance the park and to provide a gateway to the National Mall."[198]

In April 2017, the NCPC approved plans for a staircase and ramp that would connect the park with Washington's Southwest Waterfront and that would add lighting and trees to the area. The NCPC and the NPS intended the project to be an interim improvement that could be in place for ten years while the area awaits redevelopment.[176][199] Construction began on the project in September 2017 and was completed during the spring of 2018.[200]

Benjamin Banneker Park, Arlington County, Virginia

An 11 acres (4.5 ha) park in Arlington County, Virginia, memorializes Banneker and the survey of the boundaries of the District of Columbia, in which he participated.[201] The park features access to paved trails, picnic tables with charcoal grills, a playground, a playing field, a stream and a dog park.[201] The Benjamin Banneker: SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone, one of the forty boundary markers of the original District of Columbia, is within the park.[201][202]

Playground

Banneker Playground, Brooklyn, New York

The Banneker Playground in Brooklyn, New York, was originally built by the federal Works Progress Administration in 1937. In 1985, the New York City parks department renamed the 1.67 acres (0.68 ha) playground to commemorate Benjamin Banneker. The playground contains handball and basketball courts, trees and a sculpture of a sitting camel. The Benjamin Banneker Elementary School (P.S. 256), built in 1956, is near the playground.[203]

Community Centers

Banneker Community Center, Catonsville, Maryland

The Banneker Community Center (Banneker Recreation Center) in Catonsville, Maryland, is located near the intersection of the Baltimore National Pike (U.S. Route 40) and the Baltimore Beltway (Interstate 695), about 2 miles (3 km) northeast of the former site of Banneker's home and farm. A unit of the Baltimore County Department of Recreation and Parks, the facility contains ballfields, multipurpose courts and a playground.[204][a 8]

Banneker Community Center, Washington, D.C.

The Banneker Community Center in northwest Washington, D.C. is located near Howard University in the city's Columbia Heights neighborhood. The center, which is a unit of the District of Columbia Department of Parks and Recreation, contains playing fields, basketball and tennis courts, a swimming pool (Banneker pool), a computer lab and other indoor and outdoor facilities.[205] Constructed in 1934 and named for Benjamin Banneker, the center's building (formerly named the Banneker Recreation Center) was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986 because of its role as a focal point in the development of the black community in Washington, D.C.[206]

Benjamin Banneker Community Center, Bloomington, Indiana

The Benjamin Banneker Community Center in Bloomington, Indiana, contains a gymnasium, a recreation room, a kitchen, a library, a family resource center, a community garden, a cave mural, meeting rooms and other facilities.[207] Benjamin Banneker School was a segregated school for Bloomington's African American residents from 1915 to 1951. When the school desegregated, its name was changed to Fairview Annex. In 1955, the school's building became the Westside Community Center. In 1994, the Bloomington City Council changed the community center's name to commemorate the building's history as a segregated school and to re-commemorate Benjamin Banneker.[208][209] The City of Bloomington's Parks and Recreation Department operates the center.[210]

Museum

Banneker-Douglass Museum, Annapolis, Maryland

The Banneker-Douglass Museum in Annapolis, Maryland, memorializes Benjamin Banneker and Frederick Douglass.[91] The museum, which was dedicated on February 24, 1984, is the State of Maryland's official museum of African American heritage.[91][211] It is housed within and adjacent to the former Mount Moriah African Methodist Episcopal Church, which the National Park Service placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[91][212]

Planetarium

Banneker Planetarium, Catonsville, Maryland

The Banneker Planetarium in Catonsville, Maryland, is located about 2 miles (3 km) southeast of the former site of Benjamin Banneker's home and farm. The planetarium is a component of the Community College of Baltimore County's Catonsville Campus. Operated by the College's School of Mathematics and Science, the planetarium offers shows and programs to the public.[213][a 9]

Educational institutions

The names of a number of university buildings, high schools, middle schools, elementary schools, professorships and scholarships throughout the United States have commemorated Benjamin Banneker. These include:

University buildings, rooms and memorials

- Banneker Hall, Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland[214]

- Benjamin Banneker Hall, Bowie State University, Bowie, Maryland (building destroyed)[215]

- Benjamin Banneker Hall, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, Alabama[216]

- Benjamin Banneker Hall, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, Princess Anne, Maryland[217]

- Benjamin Banneker Memorial Sundial, Howard University, Washington, D.C.[17][218]

- Benjamin Banneker Room, Adele H. Stamp Student Union, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland[219]

- Benjamin Banneker Science Hall, Central State University, Wilberforce, Ohio[220]

- Benjamin Banneker Technology Complex, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, Tallahassee, Florida[221]

High schools and high school rooms

- Benjamin Banneker Academic High School, Washington, D.C.[222]

- Benjamin Banneker Academy for Community Development, Brooklyn, New York[223]

- Benjamin Banneker High School, Fulton County, Georgia[224]

- Benjamin Banneker Lecture Hall, Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, Baltimore, Maryland[225]

Middle schools

- Benjamin Banneker Charter Public School, Cambridge, Massachusetts[226]

- Benjamin Banneker Middle School, Burtonsville, Maryland[227]

- The Benjamin Banneker Preparatory Charter School, Willingboro, New Jersey[228]

Elementary Schools

- Banneker Elementary School, St. Louis, Loudoun County, Virginia[229]

- Banneker Elementary Science & Technology Magnet School, Kansas City, Kansas[230]

- Benjamin Banneker Academy, East Orange, New Jersey[231]

- Benjamin Banneker Achievement Center, Gary, Indiana[232]

- Benjamin Banneker Charter Academy of Technology, Kansas City, Missouri[233]

- Benjamin Banneker Elementary School, Chicago, Illinois[234]

- Benjamin Banneker Elementary School, Kansas City, Missouri[235]

- Benjamin Banneker Elementary School, Loveville, Maryland[236]

- Benjamin Banneker Elementary School, Milford, Delaware[237]

- Benjamin Banneker Elementary School, New Orleans, Louisiana[238]

- Benjamin Banneker School (now Benjamin Banneker Community Center), Bloomington, Indiana[208]

- Benjamin Banneker School (P.S. 256), Brooklyn, New York[239]

- Benjamin Banneker School, Parkville, Missouri (historical)[240]

- Benjamin Banneker Special Education Center, Los Angeles, California[241]

Professorships and scholarships

The names of several university professorships and scholarships commemorate Banneker. These include:

- Benjamin Banneker Professorship of American Studies and History, Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, George Washington University, Washington, D.C.[242]

- Benjamin Banneker Scholarship Program, Central State University, Wilberforce, Ohio[243]

- Banneker/Key Scholarship, Honors College, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland[244]

Awards

The names of several awards commemorate Banneker. These include:

- Benjamin Banneker Award, Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University, Huntsville, Alabama[245]

- Benjamin Banneker Award, Temple University College of Education, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[246]

- Benjamin Banneker Award for Excellence in Math and Science, Metropolitan Buffalo Alliance of Black School Educators, Buffalo, New York[247]

- Benjamin Banneker Award for Outstanding Social Commitment and Community Initiatives, American Planning Association, National Capital Area Chapter, Washington, D.C.[248]

- Benjamin Banneker Legacy Award, The Benjamin Banneker Institute for Science and Technology, Washington, D.C.[249]

Streets

The names of a number of streets throughout the United States commemorate Banneker. These include:

- Banneker Avenue, Richmond Heights, Missouri[a 10]

- Banneker Avenue North, Minneapolis, Minnesota[a 11]

- Banneker Court, Detroit, Michigan[a 12]

- Banneker Court, Mobile, Alabama[a 13]

- Banneker Court, Stone Mountain, Georgia[a 14]

- Banneker Court, Wilmington, Delaware[a 15]

- Banneker Cove, Memphis, Tennessee[a 16]

- Banneker Drive, San Diego[a 17]

- Banneker Drive, Williamsburg, Virginia[a 18]

- Banneker Drive Northeast, Washington, D.C.[a 19]

- Banneker Lane, Annapolis, Maryland[a 20]

- Banneker Place, Dallas, Texas[a 21]

- Banneker Place, Nipomo, California[a 22]

- Banneker Road, Columbia, Maryland[a 23]

- Banneker Street, Columbus, Ohio[a 24]

- Banneker Street, DeQuincy, Louisiana[a 25]

- Benjamin Banneker Boulevard, Aquasco, Maryland[a 26]

- South Banneker Avenue, Fresno, California[a 27]

- West Banneker Street, Hanford, California[a 28]

Real estate

The names of a number of buildings and apartment complexes commemorate Banneker. These include:

- Banneker Building, Columbia, Maryland[250]

- Banneker Gardens, Cumberland, Maryland (townhomes/apartments)[251]

- Banneker Homes, San Francisco[252]

- Banneker Place, Town Center, Columbia, Maryland[253]

- Banneker Place apartments, Washington, D.C.[254]

Businesses

The names of a number of businesses commemorate Banneker. These include:

- Banneker Energy, LLC, Duluth, Georgia and New Orleans, Louisiana (transportation fuel management)[255]

- Banneker, Inc., Denver, Colorado (watches and clocks)[256]

- Banneker Industries, Inc., North Smithfield, Rhode Island (supply chain management)[257]

- Banneker Ventures, LLC, Washington, D.C. and Rockville, Maryland (design, construction and contracting management)[258]

- The Banneker Group, LLC, Laurel, Maryland (general contracting and facility maintenance)[259]

Advocacy groups

The names and/or goals of several advocacy groups commemorate Banneker. These include:

- The Benjamin Banneker Association, Inc. (BANNEKERMATH.org), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[260]

- The Benjamin Banneker Center for Economic Justice and Progress, Baltimore, Maryland[261]

- The Benjamin Banneker Foundation, Fulton, Maryland[262]

- The Benjamin Banneker Institute for Science & Technology, Washington, D.C.[263]

- Washington Interdependence Council: Administrators of the Benjamin Banneker Memorial and Banneker Institute of Math & Science, Washington, D.C.[264]

Other

Other commemorations of Benjamin Banneker include:

- "Banneker",[265] a 1983 poem by Rita Dove (1993-1995 United States Poet Laureate)[266]

- Banneker City Little League, Washington, D.C.(youth baseball)[267]

- Banneker Literary Institute, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (historical)[268]

- Banneker neighborhood, Town Center, Columbia, Maryland[253]

- Benjamin Banneker Honors Math & Science Society, Washington Metropolitan Area: Washington, D.C., Virginia and Maryland[269]

- Banneker Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts (summer program in astronomical sciences)[270]

- Benjamin Banneker Mathematics Competition, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania[271]

- Benjamin Banneker obelisk, Mt. Gilboa African Methodist Episcopal Church, Oella, Maryland (see: Mount Gilboa Chapel).[272][a 29]

- Benjamin Banneker Science Fair, Delaware Valley: Delaware, Pennsylvania and New Jersey[273]

- Benjamin Banneker: SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone (milestone) of the District of Columbia: Arlington County and City of Falls Church, Virginia.[202]

- Benjamin Banneker: The Man Who Loved the Stars (1979 film starring Ossie Davis)[274]

- Benjamin Banneker: The Man Who Loved the Stars (1989 television docudrama starring Ossie Davis)[275]

- The Banneker Room, George Howard Building, Howard County Government, Ellicott City, Maryland (County Council meeting room)[276]

- The Banneker Room, The Wayside Inn, Ellicott City, Maryland (guest room)[277]

List and map of coordinates

- ↑ Coordinates of inscription of L'Enfant's name in Freedom Plaza: 38°53′45″N 77°01′53″W / 38.895838°N 77.031254°W

- ↑ Coordinates of National Park Service's historical marker in Benjamin Banneker Park, Washington, D.C.: 38°52′55″N 77°01′34″W / 38.8818496°N 77.026037°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Benjamin Banneker Historical Park, Baltimore County, Maryland: 39°16′07″N 76°46′36″W / 39.268506°N 76.776543°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Benjamin Banneker Museum, Baltimore County, Maryland: 39°16′08″N 76°46′30″W / 39.268927°N 76.775018°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Molly Banneky House: 39°16′13″N 76°46′36″W / 39.270297°N 76.776638°W

- ↑ Coordinates of replica of Benjamin Banneker's log cabin: 39°16′07″N 76°46′32″W / 39.268505°N 76.775552°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Benjamin Banneker Park, Washington, D.C.: 38°52′54″N 77°01′34″W / 38.8817128°N 77.0259833°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Benjamin Banneker Community Center, Catonsville, Maryland: 39°16′50″N 76°44′25″W / 39.2804882°N 76.7403379°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Community College of Baltimore County, Catonsville, Maryland: 39°15′12″N 76°44′08″W / 39.2534553°N 76.7355797°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Avenue, Richmond Heights, Missouri: 38°37′28″N 90°20′01″W / 38.6243918°N 90.33350°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Avenue North, Minneapolis, Minnesota: 44°59′24″N 93°17′51″W / 44.9899561°N 93.2975766°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Court, Detroit, Michigan: 42°23′28″N 82°58′30″W / 42.3910148°N 82.974933°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Court, Mobile, Alabama: 30°43′05″N 88°05′39″W / 30.7181507°N 88.0940791°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Court, Stone Mountain, Georgia: 33°50′12″N 84°10′58″W / 33.836538°N 84.1828309°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Court, Wilmington, Delaware: 39°43′28″N 75°32′45″W / 39.7243704°N 75.5459409°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Cove, Memphis, Tennessee: 35°00′15″N 90°04′18″W / 35.0041318°N 90.0717804°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Drive, San Diego: 32°42′45″N 117°01′58″W / 32.7125172°N 117.0328774°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Drive, Williamsburg, Virginia: 37°14′58″N 76°39′26″W / 37.2495039°N 76.6572029°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Drive Northeast, Washington, D.C.: 38°55′33″N 76°57′42″W / 38.9259512°N 76.9615853°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Lane, Annapolis, Maryland: 38°57′55″N 76°31′53″W / 38.9653623°N 76.5314086°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Place, Dallas, Texas: 32°47′52″N 96°47′29″W / 32.7977617°N 96.7912545°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Place, Nipomo, California: 35°01′27″N 120°32′28″W / 35.0242629°N 120.541212°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Road, Columbia, Maryland: 39°12′45″N 76°52′14″W / 39.2125185°N 76.8705726°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Street, Columbus, Ohio: 39°52′37″N 82°49′38″W / 39.8769572°N 82.8273471°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Banneker Street, DeQuincy, Louisiana: 30°26′38″N 93°25′27″W / 30.4437891°N 93.4242829°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Benjamin Banneker Boulevard, Aquasco, Maryland: 38°34′19″N 76°41′14″W / 38.5718481°N 76.6871739°W

- ↑ Coordinates of South Banneker Avenue, Fresno, California: 36°42′55″N 119°48′26″W / 36.7153949°N 119.807338°W

- ↑ Coordinates of West Banneker Street, Hanford, California: 36°18′33″N 119°39′57″W / 36.3091244°N 119.6659296°W

- ↑ Coordinates of Benjamim Banneker obelisk: 39°16′30″N 76°46′44″W / 39.2749641°N 76.778807°W

Notes

- ↑ (1) Bedini, 1969, p. 7. "The name of Benjamin Banneker, the Afro-American self-taught mathematician and almanac-maker, occurs again and again in the several published accounts of the survey of Washington City begun in 1791, but with conflicting reports of the role which he played. Writers have implied a wide range of involvement, from the keeper of horses or supervisor of the woodcutters, to the full responsibility of not only the survey of the ten mile square but the design of the city as well. None of these accounts has described the contribution which Banneker actually made."

(2) Whiteman, Maxwell. Whiteman, Maxwell, ed. BENJAMIN BANNEKER: Surveyor and Astronomer: 1731-1806: A biographical note. Banneker's Almanack and Ephemeris for the Year of Our Lord 1793; being The First After Bisixtile or Leap Year and Banneker's almanac, for the year 1795: Being the Third After Leap Year: Afro-American History Series: Rhistoric Publication No. 202 (1969 Reprint Edition). Rhistoric Publications, a division of Microsurance Inc. LCCN 72077039. OCLC 907004619. Retrieved 2017-06-14 – via HathiTrust.A number of fictional accounts of Banneker are available. All of them were dependent upon the following: Proceedings of the Maryland Historical Society for 1837 and 1854 which respectively contain the accounts of Banneker by John B. H. Latrobe and Martha E. Tyson. They were subsequently reprinted as pamphlets.

(3) Cerami, 2002, p. 142. "(Banneker) has existed in dim memory mainly on mangled ideas about his work, and even utter falsehoods that are unwise attempts to glorify a man who needs no such embellishment. ........"

(4) Johnson, Richard (2007). "Banneker, Benjamin (1731-1806)". Online Encyclopedia of Significant People and Places in African American History. BlackPast.org. Archived from the original on 2014-03-09. Retrieved 2015-05-14.(Banneker's) life and work have become enshrouded in legend and anecdote.

(5) Maryland Historical Society Library Department (2014-02-06). "The Dreams of Benjamin Banneker". Underbelly: African American History. Maryland Historical Society. Retrieved 2018-02-19.Over the 200 years since the death of Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806), his story has become a muddled combination of fact, inference, misinformation, hyperbole, and legend. Like many other figures throughout history, the small amount of surviving source material has nurtured the development of a degree of mythology surrounding his story.

Archived 2018-02-19 at the Wayback Machine. - 1 2 3 Shipler, David K. (1998). The Myths of America. A Country of Strangers: Blacks and Whites in America. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 196–197. ISBN 0679734546. OCLC 39849003. Archived from the original on 2015-06-07 – via Google Books.

The Banneker story, impressive as it was, got embellished in 1987, when the public school system in Portland, Oregon, published African-American Baseline Essays, a thick stack of loose-leaf background papers for teachers, commissioned to encourage black history instruction. They have been used in Detroit, Atlanta, Fort Lauderdale, Newark, and scattered schools elsewhere, although they have been attacked for gross inaccuracy in an entire literature of detailed criticism by respected historians. ....

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Editorial Note: Locating the Federal District: Footnote 119". Founders Online: Thomas Jefferson. National Historical Publications & Records Commission: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, last modified 2016-12-06. (Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 19, 24 January–31 March 1791, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974, pp. 3–58.). Archived from the original on 2016-12-22. Retrieved 2016-12-22.

Recent biographical accounts of Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806), a mulatto whose father was a native African and whose grandmother was English, have done his memory a disservice by obscuring his real achievements under a cloud of extravagant claims to scientific accomplishment that have no foundation in fact. The single notable exception is Silvio A. Bedini’s The Life of Benjamin Banneker (New York, 1972), a work of painstaking research and scrupulous attention to accuracy which also benefits from the author’s discovery of important and hitherto unavailable manuscript sources. However, as Bedini points out, the story of Banneker’s involvement in the survey of the Federal District “rests on extremely meager documentation” (p. 104). This consists of a single mention by TJ, two brief statements by Banneker himself, and the newspaper allusion quoted above. In consequence, Bedini’s otherwise reliable biography accepts the version of Banneker’s role in this episode as presented in reminiscences of nineteenth-century authors. These recollections, deriving in large part from members of the Ellicott family who were prompted by Quaker inclinations to justice and equality, have compounded the confusion. The nature of TJ’s connection with Banneker is treated in the Editorial Note to the group of documents under 30 Aug. 1791, but because of the obscured record it is necessary here to attempt a clarification of the role of this modest, self-taught tobacco farmer in the laying out of the national capital.

First of all, because of unwarranted claims to the contrary, it must be pointed out that there is no evidence whatever that Banneker had anything to do with the survey of the Federal City or indeed with the final establishment of the boundaries of the Federal District. All available testimony shows that he was present only during the few weeks early in 1791 when the rough preliminary survey of the ten mile square was made; that, after this was concluded and before the final survey was begun, he returned to his farm and his astronomical studies in April, accompanying Ellicott part way on his brief journey back to Philadelphia; and that thenceforth he had no connection with the mapping of the seat of government. ...

In any case, Banneker’s participation in the surveying of the Federal District was unquestionably brief and his role uncertain. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bedini, 1999, p. 136.

- ↑ (1) Bedini, 1969, p. 7. "The name of Benjamin Banneker, the Afro-American self-taught mathematician and almanac-maker, occurs again and again in the several published accounts of the survey of Washington City begun in 1791, but with conflicting reports of the role which he played. Writers have implied a wide range of involvement, from the keeper of horses or supervisor of the woodcutters, to the full responsibility of not only the survey of the ten mile square but the design of the city as well. None of these accounts has described the contribution which Banneker actually made."

(2) Cerami, 2002, pp. 142-143.

(3) Murdock. "This very well-researched book also helps lay to rest some of the myths about what Banneker did and did not do during his most unusual lifetime; unfortunately, many websites and books continue to propagate these myths, probably because those authors do not understand what Banneker actually accomplished."

(4) Toscano. "Some writers, in an effort to build up their hero, claim that Banneker was the designer of Washington. Other writers have asserted that Banneker's role in the survey is a myth without documentation. Neither group is correct. Bedini does a professional job of sorting out the truth from the falsehoods."

(5) Fasanelli, Florence D, "Benjamin Banneker's Life and Mathematics: Web of Truth? Legends as Facts; Man vs. Legend," a talk given on January 8, 2004, at the MAA/AMS meeting in Phoenix, AZ. Cited in Mahoney, John F (July 2010). "Benjamin Banneker's Inscribed Equilateral Triangle - References". Loci. Mathematical Association of America. 2. Archived from the original on 2014-02-06. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

(6) Bigbytes. "Benjamin Banneker Stories". dcsymbols.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-27. Retrieved 2013-01-27. - 1 2 3 4 (1) Levine, Michael (2003-11-10). "L'Enfant designed more than D.C.: He designed a 200-year-old controversy". History: Planning Our Capital City: Get to know the District of Columbia. DCpages.com. Archived from the original on 2003-12-06. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

(2) Brownell, Richard (2016-02-08). "Benjamin Banneker's Capital Contributions". Boundary Stones: WETA's Local History Blog. Arlington County, Virginia: WETA. Retrieved 2018-05-28. - 1 2 3 4 5 Arnebeck, Bob (2017-01-02). "Washington Examined: Seat of Empire: the General and the Plan 1790 to 1801". Blogger. Archived from the original on 2018-01-29. Retrieved 2018-01-29.