Mexican art

Mexican art consists of various visual arts that developed over the geographical area now known as Mexico. The development of these arts roughly follows the history of Mexico, divided into the prehispanic Mesoamerican era, the colonial period, with the period after Mexican War of Independence further subdivided. Mexican art is usually filled most of the time with intricate patterns.[1]

Mesoamerican art is that produced in an area that encompasses much of what is now central and southern Mexico, before the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire for a period of about 3,000 years from 1500 BCE to 1500 CE. During this time, all influences on art production were indigenous, with art heavily tied to religion and the ruling class. There was little to no real distinction among art, architecture, and writing. The Spanish conquest led to 300 years of Spanish colonial rule, and art production remained tied to religion—most art was associated with the construction and decoration of churches, but secular art expanded in the eighteenth century, particularly casta paintings, portraiture, and history painting. Almost all art produced was in the European tradition, with late colonial-era artists trained at the Academy of San Carlos, but indigenous elements remained, beginning a continuous balancing act between European and indigenous traditions.[2]

After Independence, art remained heavily European in style, but indigenous themes appeared in major works as liberal Mexico sought to distinguish itself from its Spanish colonial past. This preference for indigenous elements continued into the first half of the 20th century, with the Social Realism or Mexican muralist movement led by artists such as Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Fernando Leal, who were commissioned by the post-Mexican Revolution government to create a visual narrative of Mexican history and culture.

The strength of this artistic movement was such that it affected newly invented technologies, such as still photography and cinema, and strongly promoted popular arts and crafts as part of Mexico’s identity. Since the 1950s, Mexican art has broken away from the muralist style and has been more globalized, integrating elements from Asia, with Mexican artists and filmmakers having an effect on the global stage.

Pre-Columbian art

It is believed that the American continent's oldest rock art, 7500 years old, is found in a cave on the peninsula of Baja California.[3]

The pre-Hispanic art of Mexico belongs to a cultural region known as Mesoamerica, which roughly corresponds to central Mexico on into Central America,[4] encompassing three thousand years from 1500 BCE to 1500 CE generally divided into three eras: Pre Classic, Classic and Post Classic.[5] The first dominant Mesoamerican culture was that of the Olmecs, which peaked around 1200 BCE. The Olmecs originated much of what is associated with Mesoamerica, such as hieroglyphic writing, calendar, first advances in astronomy, monumental sculpture (Olmec heads) and jade work.[6]

They were a forerunner of later cultures such as Teotihuacan, north of Mexico City, the Zapotecs in Oaxaca and the Mayas in southern Mexico, Belize and Guatemala. While empires rose and fell, the basic cultural underpinnings of the Mesoamerica stayed the same until the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire.[6] These included cities centered on plazas, temples usually built on pyramid bases, Mesoamerican ball courts and a mostly common cosmology.[4]

While art forms such as cave paintings and rock etchings date from earlier, the known history of Mexican art begins with Mesoamerican art created by sedentary cultures that built cities, and often, dominions.[5][6] While the art of Mesoamerica is more varied and extends over more time than anywhere else in the Americas, artistic styles show a number of similarities.[1][7]

Unlike modern Western art, almost all Mesoamerican art was created to serve religious or political needs, rather than art for art’s sake. It is strongly based on nature, the surrounding political reality and the gods.[8] Octavio Paz states that "Mesoamerican art is a logic of forms, lines, and volumes that is as the same time a cosmology." He goes on to state that this focus on space and time is highly distinct from European naturalism based on the representation of the human body. Even simple designs such as stepped frets on buildings fall into this representation of space and time, life and the gods.[9]

Art was expressed on a variety of mediums such as ceramics, amate paper and architecture.[7] Most of what is known of Mesoamerican art comes from works that cover stone buildings and pottery, mostly paintings and reliefs.[1] Ceramics date from the early the Mesoamerican period. They probably began as cooking and storage vessels but then were adapted to ritual and decorative uses. Ceramics were decorated by shaping, scratching, painting and different firing methods.[8]

The earliest known purely artistic production were small ceramic figures that appeared in Tehuacán area around 1,500 BCE and spread to Veracruz, the Valley of Mexico, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Chiapas and the Pacific coast of Guatemala.[5] The earliest of these are mostly female figures, probably associated with fertility rites because of their often oversized hips and thighs, as well as a number with babies in arms or nursing. When male figures appear they are most often soldiers.[10] The production of these ceramic figures, which would later include animals and other forms, remained an important art form for 2000 years. In the early Olmec period most were small but large-scale ceramic sculptures were produced as large as 55 cm.[11][12]

After the middle pre-Classic, ceramic sculpture declined in the center of Mexico except in the Chupícuaro region. In the Mayan areas, the art disappears in the late pre-Classic, to reappear in the Classic, mostly in the form of whistles and other musical instruments. In a few areas, such as parts of Veracruz, the creation of ceramic figures continued uninterrupted until the Spanish conquest, but as a handcraft, not a formal art.[13]

Mesoamerican painting is found in various expressions—from murals, to the creation of codices and the painting of ceramic objects. Evidence of painting goes back at least to 1800 BCE and continues uninterrupted in one form or another until the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century.[14] Although it may have occurred earlier, the earliest known cases of artistic painting of monumental buildings occur in the early Classic period with the Mayas at Uaxactun and Tikal, and in Teotihuacan with walls painted in various colors.[5]

Paints were made from animal, vegetable and mineral pigments and bases.[15] Most paintings focus one or more human figures, which may be realistic or stylized, masculine, feminine or asexual. They may be naked or richly attired, but the social status of each figure is indicated in some way. Scenes often depict war, sacrifice, the roles of the gods or the acts of nobles. However, some common scenes with common people have been found as well.[16] Other subjects included gods, symbols and animals.[15] Mesoamerican painting was bi-dimensional with no efforts to create the illusion of depth. However, movement is often represented.[17]

Non-ceramic sculpture in Mesoamerica began with the modification of animal bones, with the oldest known piece being an animal skull from Tequixquiac that dates between 10,000 and 8,000 BCE.[10] Most Mesoamerican sculpture is of stone; while relief work on buildings is the most dominant, freestanding sculpture was done as well. Freestanding three-dimensional stone sculpture began with the Olmecs, with the most famous example being the giant Olmec stone heads. This disappeared for the rest of the Mesoamerican period in favor of relief work until the late post-Classic with the Aztecs.[18]

The majority of stonework during the Mesoamerican period is associated with monumental architecture that, along with mural painting, was considered an integral part of architecture rather than separate.[19] Monumental architecture began with the Olmecs in southern Veracruz and the coastal area of Tabasco in places such as San Lorenzo; large temples on pyramid bases can still be seen in sites such as Montenegro, Chiapa de Corzo and La Venta. This practice spread to the Oaxaca area and the Valley of Mexico, appearing in cities such as Monte Albán, Cuicuilco and Teotihuacan.[5][20]

These cities had a nucleus of one or more plazas, with temples, palaces and Mesoamerican ball courts. Alignment of these structures was based on the cardinal directions and astronomy for ceremonial purposes, such as focusing the sun’s rays during the spring equinox on a sculpted or painted image. This was generally tied to calendar systems.[21] Relief sculpture and/or painting were created as the structures were built. By the latter pre-Classic, almost all monumental structures in Mesoamerica had extensive relief work. Some of the best examples of this are Monte Albán, Teotihuacan and Tula.[22]

Pre-Hispanic reliefs are general lineal in design and low, medium and high reliefs can be found. While this technique is often favored for narrative scenes elsewhere in the world, Mesoamerican reliefs tend to focus on a single figure. The only time reliefs are used in the narrative sense is when several relief steles are placed together. The best relief work is from the Mayas, especially from Yaxchilan.[23]

Writing and art were not distinct as they have been for European cultures. Writing was considered art and art was often covering in writing.[9] The reason for this is that both sought to record history and the culture’s interpretation of reality.(salvatvolp14) Manuscripts were written on paper or other book-like materials then bundled into codices.[24] The art of reading and writing was strictly designated to the highest priest classes, as this ability was a source of their power over society.[14][17]

The pictograms or glyphs of this writing system were more formal and rigid than images found on murals and other art forms as they were considered mostly symbolic, representing formulas related to astronomical events, genealogy and historic events.[17] Most surviving pre-Hispanic codices come from the late Mesoamerican period and early colonial period, as more of these escaped destruction over history. For this reason, more is known about the Aztec Empire than the Mayan cultures.[15][24] Important Aztec codices include the Borgia Group of mainly religious works, some of which probably pre-date the conquest, the Codex Borbonicus, Codex Mendoza, and the late Florentine Codex, which is in a European style but executed by Mexican artists, probably drawing on earlier material that is now lost.

Olmec Head No.1, 1200–900 BCE

Olmec Head No.1, 1200–900 BCE Olmec jadeite mask, 1000 to 600 BCE

Olmec jadeite mask, 1000 to 600 BCE Las Limas Monument 1, 1000 to 600 BCE

Las Limas Monument 1, 1000 to 600 BCE Chupicuaro statuette at the Louvre, 600 to 200 BCE

Chupicuaro statuette at the Louvre, 600 to 200 BCE Jars from Casas Grandes, 12th to 15th century

Jars from Casas Grandes, 12th to 15th century Tripod vessel from Teotihuacán, 250 to 600 AD

Tripod vessel from Teotihuacán, 250 to 600 AD.jpg) Detail of a mural in Tepantitla, Teotihuacán, 100 BCE to 700 AD

Detail of a mural in Tepantitla, Teotihuacán, 100 BCE to 700 AD- Mural in Portic A of Cacaxtla.

Stucco head of K'inich Janaab Pakal I (603-683 AD), ruler of Palenque.

Stucco head of K'inich Janaab Pakal I (603-683 AD), ruler of Palenque. Zapotec mask of the bat God

Zapotec mask of the bat God Shield of Yanhuitlan

Shield of Yanhuitlan Detail from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, 14th to 15th century

Detail from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, 14th to 15th century The Aztec Sun Stone, early 16th century, on display at the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City

The Aztec Sun Stone, early 16th century, on display at the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City

Colonial era, 1521–1821

The early colonial era and indigenous artists and influences

Since the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Mexican art has been an ongoing and complex interaction between the traditions of Europe and native perspectives.[1]

Church construction After the conquest, Spaniards' first efforts were directed at evangelization and the related task of building churches, which needed indigenous labor for basic construction, but they Nahuas elaborated stonework exteriors and decorated church interiors. Indigenous craftsmen were taught European motifs, designs and techniques, but very early work, called tequitqui (Nahuatl for “vassal”), includes elements such as flattened faces and high-stiff relief.[25][26] The Spanish friars directing construction were not trained architects or engineers. They relied on indigenous stonemasons and sculptors to build churches and other Christian structures, often in the same places as temples and shrines of the traditional religion. "Although some Indians complained about the burden such labor represented, most communities considered a large and impressive church to be a reflection of their town's importance and took justifiable pride in creating a sacred place for divine worship."[27] The fact that so many colonial-era churches have survived centuries it testament to their general good construction.

The first monasteries built in and around Mexico City, such as the monasteries on the slopes of Popocatepetl, had Renaissance, Plateresque, Gothic or Moorish elements, or some combination. They were relatively undecorated, with building efforts going more towards high walls and fortress features to ward off attacks.[28] The construction of more elaborate churches with large quantities of religious artwork would define much of the artistic output of the colonial period. Most of the production was related to the teaching and reinforcement of Church doctrine, just as in Europe. Religious art set the rationale for Spanish domination over the indigenous. Today, colonial-era structures and other works exist all over the country, with a concentration in the central highlands around Mexico City.[29]

Feather work was a highly valued skill of prehispanic central Mexico that continued into the early colonial era. Spaniards were fascinated by this form of art, and indigenous feather workers (amanteca) produced religious images in this medium, mainly small "paintings", as well as religious vestments.[30][31]

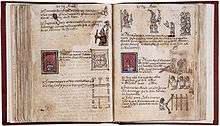

Indigenous writings Indians continued production of written manuscripts in the early colonial era, especially codices in the Nahua area of central Mexico. An important early manuscript that was commissioned for the Spanish crown was Codex Mendoza, named after the first viceroy of Mexico, Don Antonio de Mendoza, which shows the tribute delivered to the Aztec ruler from individual towns as well as descriptions of proper comportment for the common people. A far more elaborate project utilizing indigenous scribes illustration is the project resulting in the Florentine Codex directed by Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún. Other indigenous manuscripts in the colonial era include the Huexotzinco Codex and Codex Osuna.

An important type of manuscript from the early period were pictorial and textual histories of the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs from the indigenous viewpoint. The early Lienzo de Tlaxcala illustrated the contributions the Spaniards' Tlaxcalan allies made to the defeat of the Aztec empire, as well the Hernán Cortés and his cultural translator Doña Marina (Malinche).

Painting Most Nahua artists producing this visual art are anonymous. An exception is the work of Juan Gerson, who ca. 1560 decorated the vault of the Franciscan church in the Nahua town of Tecamachalco,(Puebla state), with individual scenes from the Old Testament.[32]

While colonial art remained almost completely European in style, with muted colors and no indication of movement—the addition of native elements, which began with the tequitqui, continued. They were never the center of the works, but decorative motifs and filler, such as native foliage, pineapples, corn, and cacao.[33] Much of this can be seen on portals as well as large frescoes that often decorated the interior of churches and the walls of monastery areas closed to the public.[34]

The earliest of Mexico's colonial artists were Spanish-born who came to Mexico in the middle of their careers. This included mendicant friars, such as Fray Alonso López de Herrera. Later, most artists were born in Mexico, but trained in European techniques, often from imported engravings. This dependence on imported copies meant that Mexican works preserved styles after they had gone out of fashion in Europe.[1] In the colonial period, artists worked in guilds, not independently. Each guild had its own rules, precepts, and mandates in technique—which did not encourage innovation.[35]

Gallery

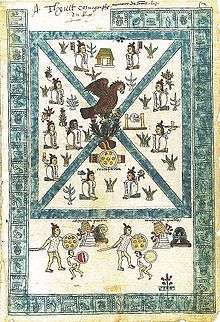

Founding of Tenochtitlan in Codex Mendoza ca. 1541.

Founding of Tenochtitlan in Codex Mendoza ca. 1541. Towns owing tribute to the Aztec empire shown in Codex Mendoza ca. 1541

Towns owing tribute to the Aztec empire shown in Codex Mendoza ca. 1541 Image of Cortés and Malinche in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, chronicling the conquest of central Mexico from the Tlaxcalans' viewpoint.

Image of Cortés and Malinche in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, chronicling the conquest of central Mexico from the Tlaxcalans' viewpoint. Florentine Codex Book XII, showing death and cremation of Moctezuma

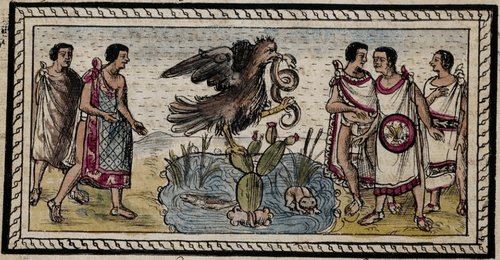

Florentine Codex Book XII, showing death and cremation of Moctezuma Native illustration of Diego Durán's history of ancient Mexico, showing the founding of Tenochtitlan

Native illustration of Diego Durán's history of ancient Mexico, showing the founding of Tenochtitlan

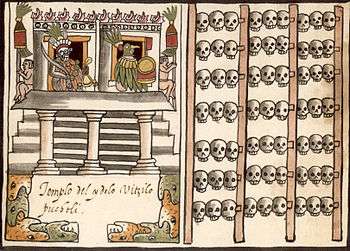

Codex Ramirez, A depiction of a tzompantli, or skull rack, associated with the depiction of a temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli from Juan de Tovar's manuscript.

Codex Ramirez, A depiction of a tzompantli, or skull rack, associated with the depiction of a temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli from Juan de Tovar's manuscript. Nezahualpilli, tlatoani of Texcoco. Codex Ixtlilxochitl ca. 1582.

Nezahualpilli, tlatoani of Texcoco. Codex Ixtlilxochitl ca. 1582. A page of the Badinus Herbal, 16th c.

A page of the Badinus Herbal, 16th c. Huexotzinco Codex; the panel contains an image of the Virgin and Child and symbolic representations of tribute paid to the administrators

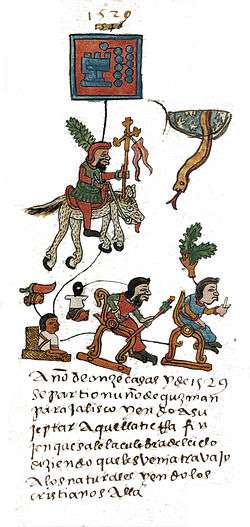

Huexotzinco Codex; the panel contains an image of the Virgin and Child and symbolic representations of tribute paid to the administrators Conquistador Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán as depicted in Codex Telleriano Remensis, a 16th c. pictorial annal/history

Conquistador Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán as depicted in Codex Telleriano Remensis, a 16th c. pictorial annal/history

- Juan Gerson's religious paintings in the Franciscan church of Tecamachalco, Puebla, 1562.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, Woman of the Apocalypse (Mujer del Apocalipsis), 1686

Cristóbal de Villalpando, Woman of the Apocalypse (Mujer del Apocalipsis), 1686.png) Cristóbal de Villpando, The Virgin of the Apocalypse (La Virgen de la Apocalipsis). Late 17th century

Cristóbal de Villpando, The Virgin of the Apocalypse (La Virgen de la Apocalipsis). Late 17th century Cristóbal de Villalpando, Saint Rose tempted by the devil (Santa rosa tentada por el demonio), ca. 1695/1697

Cristóbal de Villalpando, Saint Rose tempted by the devil (Santa rosa tentada por el demonio), ca. 1695/1697 Cristóbal de Villalpando, Apparition of Saint Michael (Aparición de San Miguel), ca. 1686–1688

Cristóbal de Villalpando, Apparition of Saint Michael (Aparición de San Miguel), ca. 1686–1688 Cristóbal de Villalpando, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico city (Vista de la Plaza Mayor de la Ciudad de México), 1695

Cristóbal de Villalpando, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico city (Vista de la Plaza Mayor de la Ciudad de México), 1695 Cristóbal de Villalpando, Saint Paul (San Pablo), 1670–1680

Cristóbal de Villalpando, Saint Paul (San Pablo), 1670–1680.jpg) Cristóbal de Villalpando, Madonna of the Stairs (La Virgen de la Escalera), 1680–1690

Cristóbal de Villalpando, Madonna of the Stairs (La Virgen de la Escalera), 1680–1690 Juan Correa, The liberal arts and the four elements (Las artes liberales y los cuatro elementos). 1670

Juan Correa, The liberal arts and the four elements (Las artes liberales y los cuatro elementos). 1670

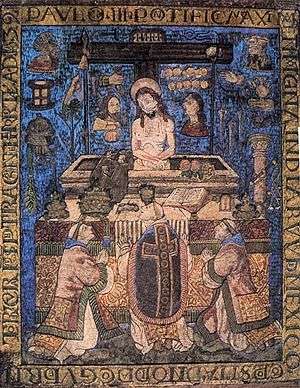

Mexican Baroque

Baroque painting became firmly established in Mexico by the middle of the 17th century with the work of Spaniard Sebastián López de Arteaga. His painting is exemplified by the canvas called Doubting Thomas from 1643. In this work, the Apostle Thomas is shown inserting his finger in the wound in Christ's side to emphasize Christ’s suffering. The caption below reads "the Word made flesh" and is an example of Baroque's didactic purpose.[34]

One difference between painters in Mexico and their European counterparts is that they preferred realistic directness and clarity over fantastic colors, elongated proportions and extreme spatial relationships. The goal was to create a realistic scene in which the viewer could imagine himself a part of. This was a style created by Caravaggio in Italy, which became popular with artists in Seville, from which many migrants came to New Spain came.[34] Similarly, Baroque free standing sculptures feature life-size scales, realistic skin tones and the simulation of gold-threaded garments through a technique called estofado, the application of paint over gold leaf.[34]

The most important later influence to Mexican and other painters in Latin America was the work of Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens, known through copies made from engravings and mezzotint techniques. His paintings were copied and reworked and became the standard for both religious and secular art.[34] Later Baroque paintings moved from the confines of altarpieces to colossal freestanding canvases on church interiors. One of the best known Mexican painters of this kind of work was Cristóbal de Villalpando. His work can be seen in the sacristy of the Mexico City Cathedral, which was done between 1684 and 1686. These canvases were glued directly onto the walls with arched frames to stabilize them, and placed just under the vaults of the ceiling. Even the fresco work of the 16th century was not usually this large.[34] Another one of Villalpando's works is the cupola of the Puebla Cathedral in 1688. He used Rubens’ brush techniques and the shape of the structure to create a composition of clouds with angels and saints, from which a dove descends to represent the Holy Spirit. The light from the cupola’s windows is meant to symbolize God’s grace.[34] Juan Rodríguez Juárez (1675–1728) and mulatto artist Juan Correa (1646–1716) were also prominent painters of the baroque era. Correa's most famous student, José de Ibarra (1685–1756) was also mixed-race. One of Mexico's finest painters, Miguel Cabrera (1695–1768), was possibly mixed race.[36]

The church produced the most important works of the seventeenth century. Among the important painters were Baltasar de Echave Ibia and his son Baltasar Echave Rioja, also Luis Juárez and his son José Juárez, Juan Correa, Cristóbal de Villalpando, Rodrigo de la Piedra, Antonio de Santander, Polo Bernardino, Juan de Villalobos, Juan Salguero and Juan de Herrera. Juan Correa, worked from 1671 to 1716 and reached great prestige and reputation for the quality of its design and scale of some of his works. Among the best known: 'Apocalypse in the Cathedral of Mexico', 'Conversion of St. Mary Magdalene', now in the 'Pinacoteca Virreinal' and 'Santa Catarina and Adam and Eve casting out of paradise', the latter located in the National Museum of Viceroyalty of Tepotzotlán.[37]

Colonial religious art was sponsored by Church authorities and private patrons. Sponsoring the rich ornamentation of churches was a way for the wealthy to gain prestige.[29] In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Mexico City was one of the wealthiest in the world, mostly due to mining and agriculture, and was able to support a large art scene.[38]

Gallery

Portrait of Hernando Cortés, conqueror of Mexico. Unknown artist. 16th century.

Portrait of Hernando Cortés, conqueror of Mexico. Unknown artist. 16th century. Official Portrait of Don Antonio de Mendoza, first viceroy of New Spain. Unknown artist. 1535.

Official Portrait of Don Antonio de Mendoza, first viceroy of New Spain. Unknown artist. 1535. Official Portrait of Don Pedro Moya de Contreras, first secular cleric to be archbishop of Mexico and first cleric to serve as viceroy. Unknown artist.

Official Portrait of Don Pedro Moya de Contreras, first secular cleric to be archbishop of Mexico and first cleric to serve as viceroy. Unknown artist.- The Lactación de Santo Domingo, by Cristóbal de Villalpando painted near the end of the 17th century.

St Ignatius in the Holy Land, Cristóbal de Villalpando (1710)

St Ignatius in the Holy Land, Cristóbal de Villalpando (1710) Juan Correa La Pascua de María, 1698.

Juan Correa La Pascua de María, 1698. Juan Rodríguez Juárez Portrait of Viceroy Fernando de Alencastre Noroña y Silva, duque de Linares y marqués de Valdefuentes, ca. 1717

Juan Rodríguez Juárez Portrait of Viceroy Fernando de Alencastre Noroña y Silva, duque de Linares y marqués de Valdefuentes, ca. 1717 Josep Antonio de Ayala, The del Valle family at the feet the Virgin of Loreto, 1769. In the collections of the Museo Soumaya

Josep Antonio de Ayala, The del Valle family at the feet the Virgin of Loreto, 1769. In the collections of the Museo Soumaya Inmaculada del Apocalipsis, Pinacoteca de La Profesa, México, by José de Ibarra

Inmaculada del Apocalipsis, Pinacoteca de La Profesa, México, by José de Ibarra Virgin of Guadalupe, ca. 1700

Virgin of Guadalupe, ca. 1700 History painting of the Spanish Conquest of Tenochtitlan, 17th century

History painting of the Spanish Conquest of Tenochtitlan, 17th century_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Folding Screen with Indian Wedding and Voladores, ca. 1690

Folding Screen with Indian Wedding and Voladores, ca. 1690

Neoclassical and Secular Art

While most commissioned art was for churches, secular works were commissioned as well. Portrait painting was known relatively early in the colonial period, mostly of viceroys and archbishops. Beginning in the late Baroque period, portrait painting of local nobility became a significant genre. Two notable painters of this type are brothers Nicolás and Juan Rodríguez Juárez. These works followed European models, with symbols of rank and titles either displayed unattached in the outer portions or worked into another element of the paintings such as curtains.[34]

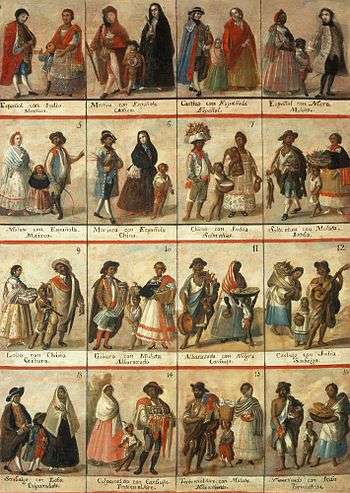

Another type of secular colonial painting is called casta paintings referring to the depiction of racial hierarchy racially in eighteenth-century New Spain. Some were likely commissioned by Spanish functionaries as souvenirs of Mexico. A number of artists of the era created casta paintings, including Miguel Cabrera, José de Ibarra, Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, Francisco Clapera, and Luis de Mena, but most casta paintings are unsigned. Ibarra, Morlete, and possibly Cabrera were of mixed race and born outside Mexico City.[39] Mena's only known casta painting links the Virgin of Guadalupe and the casta system, as well as depictions of fruits and vegetables and scenes of everyday life in mideighteenth-century Mexico. It is one of the most-reproduced examples of casta paintings, one of the small number that show the casta system on a single canvas rather than up to 16 separate paintings. It is unique in uniting the thoroughly secular genre of casta painting with a depiction of the Virgin of Guadalupe.[40] Production of these paintings stopped after the Mexican War of Independence, when legal racial categories were repudiated in independent Mexico. Until the run-up to the 500th anniversary of the Columbus's 1492 voyage, casta paintings were of little or no interest, even to art historians, but scholars began systematically studying them as a genre.[41][42][43]

Mexico was a crossroads of trade in the colonial period, with goods from Asia and Europe mixing with those natively produced. This convergence is most evident in the decorative arts of New Spain.[38] It was popular among the upper classes to have a main public room, called a salon de estrado, to be covered in rugs and cushions for women to recline in Moorish fashion. Stools and later chairs and settees were added for men. Folding screens were introduced from Japan, with Mexican-style ones produced called biombos The earliest of these Mexican made screens had oriental designs but later ones had European and Mexican themes. One example of this is a screen with the conquest of Mexico one side and an aerial view of Mexico City on the other at the Franz Mayer Museum.[38]

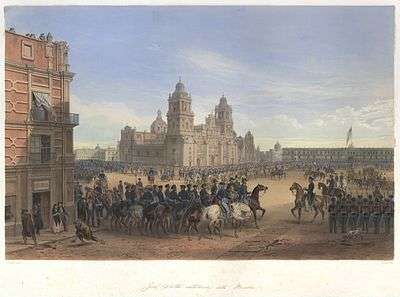

The Crown promoted the establishment in Mexico of the Neoclassical style of art and architecture, which had become popular in Spain. This style was a reinterpretation of Greco-Roman references and its use was a way to reinforce European dominance in the Spain’s colonies. One Neoclassical artist from the Academy at the end of the colonial period was Manuel Tolsá. He first taught sculpture at the Academy of San Carlos and then became its second director. Tolsá designed a number of Neoclassical buildings in Mexico but his best known work is an equestrian status of King Charles IV in bronze cast in 1803 and originally placed in the Zócalo. As of 2011 it can be seen at the Museo Nacional de Arte.[44]

Along with the construction of temples and houses artistic religious themes proliferated. In New Spain, as in the rest of the New World, since the seventeenth century, particularly during the eighteenth century, the portrait became an important part of the artistic repertoire. In a society characterized by a deep religious feeling which was imbued, it was expected that many portraits reflected the moral virtues and piety of the model.[45]

Some prominent painters of this period are: Cristóbal de Villalpando, Juan Correa, José de Ibarra, Joseph Mora, Nicolas Rodriguez Juarez, Francisco Martinez, Miguel Cabrera, Andrés López and Nicolás Enríquez. Sebastian Zalcedo painted ca. 1780 a beautiful allegory of the Virgin of Guadalupe in oil on copper foil. In this century Josep Antonio de Ayala was a prominent artist, who is known for painting The family of the Valley at the foot of Our Lady of Loreto c. 1769. This devotional painting was commissioned to be done for the children of the del Valle family in memory of his parents and is characteristic of the painting of this century.[46]

A description of colonial art says: "In the "Sponsorship of Saint Joseph on the Caroline College", Saint Joseph is seen as a major figure of the work, who carries on his left side the child Jesus. Two archangels flank him and maintain its long purple robe. At the top two little angels are observed with intent to crown the holy". "For centuries, the work was attributed to Manuel Caro, but the meticulous restoration work allowed to find the signature of the original author. Miguel Cabrera"[47]

In the 18th century, artists increasingly included the Latin phrase pinxit Mexici (painted in Mexico) on works bound for the European market as a sign of pride in their artistic tradition.[48]

The Academy of San Carlos

The last colonial era art institution established was the Academy of San Carlos in 1783.[44] While the depiction of saints consumed most artistic efforts, they were not without political effects. The most important of these was the rise of the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe as an American rather than European saint, representative of a distinct identity.[49]

By the late 18th century, Spain’s colonies were becoming culturally independent from Spain, including its arts. The Academy was established by the Spanish Crown to regain control of artistic expression and the messages it disseminated. This school was staffed by Spanish artists in each of the major disciplines, with the first director being Antonio Gil.[44] The school became home to a number of plaster casts of classic statues from the San Fernando Fine Arts Academy in Spain, brought there for teaching purposes. These casts are on display in the Academy's central patio.[50] The Academy of San Carlos survived into post-independence Mexico.

Gallery

Rafael Ximeno y Planes, director of painting at the Academy of San Carlos, The Miracle of the Little Spring (1813)

Rafael Ximeno y Planes, director of painting at the Academy of San Carlos, The Miracle of the Little Spring (1813)_Cervantes_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Miguel Cabrera (1695–1768). Doña María de la Luz Padilla y Gómez de Cervantes, ca. 1760. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum

Miguel Cabrera (1695–1768). Doña María de la Luz Padilla y Gómez de Cervantes, ca. 1760. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum The consecration of pagan temples and the first mass in Mexico-Tenochtitlan by José Vivar y Valderrama, ca. 1752. Oil on canvas.

The consecration of pagan temples and the first mass in Mexico-Tenochtitlan by José Vivar y Valderrama, ca. 1752. Oil on canvas. Las castas. Anonymous, 18th century, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlán, Mexico.

Las castas. Anonymous, 18th century, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlán, Mexico. Baptism of Ixtlilxochitl by José Vivar y Valderrama, 18th century.

Baptism of Ixtlilxochitl by José Vivar y Valderrama, 18th century. A Biombo screen with a depiction of the Spanish conquest of Mexico at the Franz Mayer Museum

A Biombo screen with a depiction of the Spanish conquest of Mexico at the Franz Mayer Museum- Tile Mosaic of the Coat of arms of Villa Rica, Veracruz, the first town council founded by Spaniards. Mosaic located in Mexico City

Indian Collecting Cochineal with a Deer Tail by José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez (1777)

Indian Collecting Cochineal with a Deer Tail by José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez (1777) Josep Antonio de Ayala, La familia del Valle a los pies de la Virgen de Loreto (The family of the Valley at the foot of the Madonna of Loreto), 1769

Josep Antonio de Ayala, La familia del Valle a los pies de la Virgen de Loreto (The family of the Valley at the foot of the Madonna of Loreto), 1769 Preliminary drawing for the frontispiece of the Coat of Arms of Mexico, ca. 1743.

Preliminary drawing for the frontispiece of the Coat of Arms of Mexico, ca. 1743. The Parian (El Parián), ca. 1770

The Parian (El Parián), ca. 1770 Manuel Arellano, Inauguration of the Sanctuary of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico city (Traslado de la imagen y dedicación del santuario de Guadalupe en la Ciudad de México), 1709

Manuel Arellano, Inauguration of the Sanctuary of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico city (Traslado de la imagen y dedicación del santuario de Guadalupe en la Ciudad de México), 1709 Miguel Cabrera, Painting of Castes (Pintura de las Castas), 1763

Miguel Cabrera, Painting of Castes (Pintura de las Castas), 1763 Portrait of family Fagoga Arozqueta (Retrato de la Familia Fagoga Arozqueta), 1730

Portrait of family Fagoga Arozqueta (Retrato de la Familia Fagoga Arozqueta), 1730

Independence to the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, 1821–1911

Early Post-independence era the Mid Nineteenth Century

.svg.png)

Artists of the independence era in Mexico (1810–21) produced works showing the insurgency's heroes. A portrait of secular cleric José María Morelos in his military uniform was painted by an unknown artist. The portrait is typical of those from the late eighteenth century, with framing elements, a formal caption, and new elements being iconography of the emerging Mexican nationalism, including the eagle atop the nopal cactus, which became the central image for the Mexican flag.[51] Morelos was the subject of a commissioned statue, with Pedro Patiño Ixtolinque, who trained at the Academy of San Carlos and remained an important sculptor through the era of era independence.[52]

The Academy of San Carlos remained the center of academic painting and the most prestigious art institution in Mexico until the Mexican War of Independence, during which it was closed.[53] Despite its association with the Spanish Crown and European painting tradition, the Academy was reopened by the new government after Mexico gained full independence in 1821. Its former Spanish faculty and students either died during the war or returned to Spain, but when it reopened it attracted the best art students of the country, and continued to emphasize classical European traditions until the early 20th century.[53][54]

The academy was renamed to the National Academy of San Carlos. The new government continued to favor Neoclassical as it considered the Baroque a symbol of colonialism. The Neoclassical style continued in favor through the reign of Maximilian I although President Benito Juárez supported it only reluctantly, considering its European focus a vestige of colonialism.[50]

Despite Neoclassicism’s association with European domination, it remained favored by the Mexican government after Independence and was used in major government commissions at the end of the century. However, indigenous themes appeared in paintings and sculptures. One indigenous figure depicted in Neoclassical style is Tlahuicol, done by Catalan artist Manuel Vilar in 1851. In 1887, Porfirio Díaz commissioned the statue of the last Aztec emperor, Cuauhtémoc, which can be seen on Paseo de la Reforma. Cuauhtémoc is depicted with a toga-like cloak with a feathered headdress similar to an Etruscan or Trojan warrior rather than an Aztec emperor. The base has elements reminiscent of Mitla and Roman architecture. This base contains bronze plates depicting scenes from the Spanish conquest, but focusing on the indigenous figures.[54]

There were two reasons for this shift in preferred subject. The first was that Mexican society denigrated colonial culture—the indigenous past was seen as more truly Mexican.[38] The other factor was a worldwide movement among artists to confront society, which began around 1830. In Mexico, this anti-establishment sentiment was directed at the Academy of San Carlos and its European focus.[55]

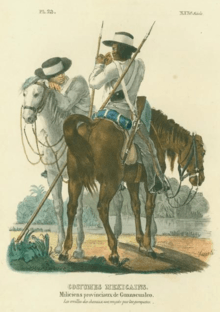

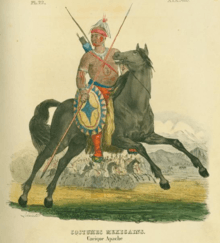

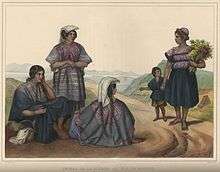

In the first half of the 19th century, the Romantic style of painting was introduced into Mexico and the rest of Latin America by foreign travelers interested in the newly independent country. One of these was Bavarian artist Johann Moritz Rugendas, who lived in the country from 1831 to 1834. He painted scenes with dynamic composition and bright colors in accordance with Romantic style, looking for striking, sublime, and beautiful images in Mexico as well as other areas of Latin America. However much of Rugendas's works are sketches for major canvases, many of which were never executed. Others include Englishman Daniel Egerton, who painted landscapes in the British Romantic tradition, and German Carl Nebel, who primarily created lithographs of the various social and ethnic populations of the country.[56]

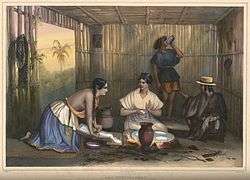

A number of native-born artists at the time followed the European Romantic painters in their desire to document the various cultures of Mexico. These painters were called costumbristas, a word deriving from costumbre (custom). The styles of these painters were not always strictly Romantic, involving other styles as well. Most of these painters were from the upper classes and educated in Europe. While the European painters viewed subjects as exotic, the costumbristas had a more nationalistic sense of their home countries. One of these painters was Agustín Arrieta from Puebla, who applied realistic techniques to scenes from his home city, capturing its brightly painted tiles and ceramics. His scenes often involved everyday life such as women working in kitchen and depicted black and Afro-Mexican vendors.[57]

Late Nineteenth Century to the Revolution

In the mid-to late 19th century Latin American academies began to shift away from severe Neoclassicism to “academic realism”. Idealized and simplified depictions became more realistic, with emphasis on details. Scenes in this style were most often portraits of the upper classes, Biblical scenes, and battles—especially those from the Independence period. When the Academy of San Carlos was reopened after a short closure in 1843, its new Spanish and Italian faculty pushed this realist style. Despite government support and nationalist themes, native artists were generally shorted in favor of Europeans.[58]

One of the most important painters in Mexico in the mid 19th century was Catalan Pelegrí Clavé, who painted landscapes but was best known for his depictions of the intellectual elite of Mexico City. Realist painters also attempted to portray Aztec culture and people by depicting settings inhabited by indigenous people, using live indigenous models and costumes based on those in Conquest era codices. One of these was Félix Parra, whose depictions of the conquest empathized with the suffering of the indigenous. In 1869, José Obregón painted The Discovery of Pulque; he based his depictions of architecture on Mixtec codices, but misrepresented temples as a setting for a throne.[58]

The art of the 19th century after Independence is considered to have declined, especially during the late 19th century and early 20th, during the regime of Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911). Although during this time, painting, sculpture, and the decorative arts were often limited to imitation of European styles,[59] the emergence of young artists, such as Diego Rivera and Saturnino Herrán, increased the focus on Mexican-themed works. This meant that following the military phase of the Mexican Revolution in the 1920s, Mexican artists made huge strides is forging a robust artistic nationalism.

In this century there are examples of murals such as folkloric style created between 1855 and 1867 in La Barca, Jalisco.[60]

Highlights at this time: Pelegrín Clavé, Juan Cordero, Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez and José Agustín Arrieta. In Mexico, in 1846 he was hired to direct Pelegrín Clavé's reopening of the Academy of San Carlos, a body from which he promoted the historical and landscaping themes with a pro-European vision.[61]

Gallery

Entrance of Agustín de Iturbide to Mexico City in 1821. Unknown artist, no date.

Entrance of Agustín de Iturbide to Mexico City in 1821. Unknown artist, no date. Claudio Linati, Mexican Water carrier

Claudio Linati, Mexican Water carrier Claudio Linati Militia of Guazacualco

Claudio Linati Militia of Guazacualco Claudio Linati Apache chief

Claudio Linati Apache chief Carl Nebel Las Tortilleras, one of 50 plates in his Voyage pittoresque et archéologique dans la partie la plus intéressante du Mexique

Carl Nebel Las Tortilleras, one of 50 plates in his Voyage pittoresque et archéologique dans la partie la plus intéressante du Mexique Carl Nebel's depiction of Sierra Indians.

Carl Nebel's depiction of Sierra Indians.

Casimiro Castro Mexicans in a rural scene outside Mexico City (1855)

Casimiro Castro Mexicans in a rural scene outside Mexico City (1855) Agustín Arrieta, Tertulia de pulquería, 1851

Agustín Arrieta, Tertulia de pulquería, 1851 Agustín Arrieta, Cuadro de comedor, pintado entre 1857 y 1859, oleo sobre tela

Agustín Arrieta, Cuadro de comedor, pintado entre 1857 y 1859, oleo sobre tela Agustín Arrieta, El Costeño the painting shows a man from the coast, likely Veracruz, holding a basket of fruits including mamey, tuna and pitahaya.

Agustín Arrieta, El Costeño the painting shows a man from the coast, likely Veracruz, holding a basket of fruits including mamey, tuna and pitahaya. Frederick Catherwood, Main temple at Tulum, from Views of Ancient Monuments.

Frederick Catherwood, Main temple at Tulum, from Views of Ancient Monuments. Frederick Catherwood Lithograph of Stela D. Copan (1844), from Views of Ancient Monuments.

Frederick Catherwood Lithograph of Stela D. Copan (1844), from Views of Ancient Monuments. Pedro Gualdi, Gran Teatro Nacional de México/Teatro Santa Anna, Mexico City

Pedro Gualdi, Gran Teatro Nacional de México/Teatro Santa Anna, Mexico City Pedro Gualdi, Interior of the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico

Pedro Gualdi, Interior of the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico Juan Cordero, Portrait of General Antonio López de Santa Anna's wife, Doña Dolores Tosta de Santa Anna. (1855)

Juan Cordero, Portrait of General Antonio López de Santa Anna's wife, Doña Dolores Tosta de Santa Anna. (1855) Christopher Columbus at the Court of the Catholic Monarchs (painted in Italy, 1850/1) by Juan Cordero

Christopher Columbus at the Court of the Catholic Monarchs (painted in Italy, 1850/1) by Juan Cordero- José María Jara (1867–1939), Foundation of Mexico City. Museo Nacional de Arte. (1889)

El Inspiración de Cristobal Colon by José Obregon. (1856)

El Inspiración de Cristobal Colon by José Obregon. (1856) The Discovery of Pulque by José Obregón at the Museo Nacional de Arte. (1869)

The Discovery of Pulque by José Obregón at the Museo Nacional de Arte. (1869)- Félix Parra, Fray Bartolomé de las Casas (1875) exhibited at the Centennial International Exposition of Philadelphia in 1876.

- Matanza de Cholula, by Félix Parra. (1875)

Leandro Izaguirre Torture of Cuauhtémoc (1892)

Leandro Izaguirre Torture of Cuauhtémoc (1892) Patio del Exconvento de San Agustín, José María Velasco

Patio del Exconvento de San Agustín, José María Velasco View of the Valley of Mexico by José María Velasco

View of the Valley of Mexico by José María Velasco.png) Oil painting of Vicente Guerrero, leader of independence and president of Mexico. Ramón Sagredo (1865)

Oil painting of Vicente Guerrero, leader of independence and president of Mexico. Ramón Sagredo (1865) Painting of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, considered the father of Mexican independence, by Antonio Fabrés

Painting of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, considered the father of Mexican independence, by Antonio Fabrés Joaquín Clausell, Countryside with forest and river.

Joaquín Clausell, Countryside with forest and river. Saturnino HerránLa cosecha ("The Harvest"), 1909

Saturnino HerránLa cosecha ("The Harvest"), 1909 Saturnino Herrán La ofrenda ("The Offering"), 1913

Saturnino Herrán La ofrenda ("The Offering"), 1913.jpg) Saturnino Herrán Mujer en Tehuantepec ("Woman of Tehuantepec) 1914

Saturnino Herrán Mujer en Tehuantepec ("Woman of Tehuantepec) 1914

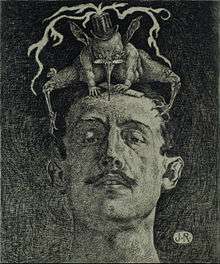

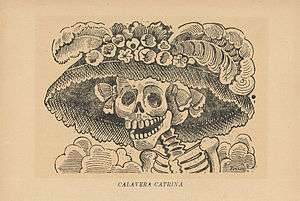

José Guadalupe Posada, Calavera Catrina, mocking the styles of elite women of the late nineteenth century

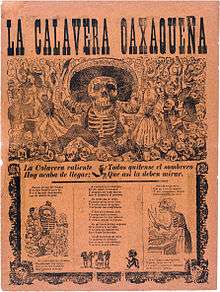

José Guadalupe Posada, Calavera Catrina, mocking the styles of elite women of the late nineteenth century José Guadalupe Posada, 1903, Calavera oaxaqueña. Posada published illustrations for many broadsheets

José Guadalupe Posada, 1903, Calavera oaxaqueña. Posada published illustrations for many broadsheets

20th century

The Academy of San Carlos continued to advocate classic, European-style training until 1913. In this year, the academy was partially integrated with National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Between 1929 and the 1950s, the academy’s architecture program was split off as a department of the university; the programs in painting, sculpture, and engraving were renamed the National School of Expressive Arts, now the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (ENAP). Both moved to the south of the city in the mid-20th century, to Ciudad Universitaria and Xochimilco respectively, leaving only some graduate programs in fine arts in the original academy building in the historic center. ENAP remains one of the main centers for the training of Mexico’s artists.[50]

Mexican muralism and Revolutionary art

While a shift to more indigenous and Mexican themes appeared in the 19th century, the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1920 had a dramatic effect on Mexican art.[50][53] The conflict resulted in the rise of the Partido Revolucionario Nacional (renamed the Partido Revolucionario Institucional), which took the country in a socialist direction. The government became an ally to many of the intellectuals and artists in Mexico City[33][38] and commissioned murals for public buildings to reinforce its political messages including those that emphasized Mexican rather than European themes. These were not created for popular or commercial tastes; however, they gained recognition not only in Mexico, but in the United States.[62]

This production of art in conjunction with government propaganda is known as the Mexican Modernist School or the Mexican Muralist Movement, and it redefined art in Mexico.[63] Octavio Paz gives José Vasconcelos credit for initiating the Muralist movement in Mexico by commissioning the best-known painters in 1921 to decorate the walls of public buildings. The commissions were politically motivated—they aimed to glorify the Mexican Revolution and redefine the Mexican people vis-à-vis their indigenous and Spanish past.[64]

The first of these commissioned paintings were at San Ildefonso done by Fernando Leal, Fermín Revueltas, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Diego Rivera. The first true fresco in the building was the work of Jean Charlot. However, technical errors were made in the construction of these murals: a number of them began to blister and were covered in wax for preservation.[65] Roberto Montenegro painted the former church and monastery of San Pedro y San Pablo, but the mural in the church was painted in tempera and began to flake. In the monastery area, Montenegro painted the Feast of the Holy Cross, which depicts Vasconcelos as the protector of Muralists. Vasconcelos was later blanked out and a figure of a woman was painted over him.[66]

The first protagonist in the production of modern murals in Mexico was Dr. Atl. Dr Atl was born “Gerard Murillo” in Guadalajara in 1875. He changed his name in order to identify himself as Mexican. Atl worked to promote Mexico’s folk art and handcrafts. While he had some success as a painter in Guadalajara, his radical ideas against academia and the government prompted him to move to more liberal Mexico City. In 1910, months before the start of the Mexican Revolution, Atl painted the first modern mural in Mexico. He taught major artists to follow him, including those who came to dominate Mexican mural painting.[59]

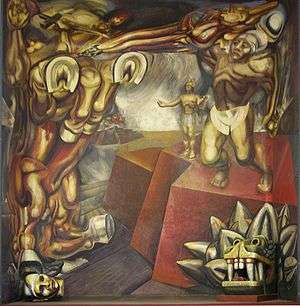

The muralist movement reached its height in the 1930s with four main protagonists: Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Fernando Leal. It is the most studied part of Mexico’s art history.[33][38][67] All were artists trained in classical European techniques and many of their early works are imitations of then-fashionable European paintings styles, some of which were adapted to Mexican themes.[1][63] The political situation in Mexico from the 1920s to 1950s and the influence of Dr. Atl prompted these artists to break with European traditions, using bold indigenous images, lots of color, and depictions of human activity, especially of the masses, in contrast to the solemn and detached art of Europe.[33]

Preferred mediums generally excluded traditional canvases and church porticos and instead were the large, then-undecorated walls of Mexico’s government buildings. The main goal in many of these paintings was the glorification of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic past as a definition of Mexican identity.[33] They had success in both Mexico and the United States, which brought them fame and wealth as well as Mexican and American students.[62]

These muralists revived the fresco technique for their mural work, although Siqueiros moved to industrial techniques and materials such as the application of pyroxilin, a commercial enamel used for airplanes and automobiles.[33] One of Rivera’s earliest mural efforts emblazoned the courtyard of the Ministry of Education with a series of dancing tehuanas (natives of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico). This four-year project went on to incorporate other contemporary indigenous themes, and it eventually encompassed 124 frescoes that extended three stories high and two city blocks long.[33] The Abelardo Rodriguez Market was painted in 1933 by students of Diego Rivera, one of whom was Isamu Noguchi.[68]

Another important figure of this time period was Frida Kahlo, the wife of Diego Rivera. While she painted canvases instead of murals, she is still considered part of the Mexican Modernist School as her work emphasized Mexican folk culture and colors.[33][69] Kahlo's self-portraits during the 1930s and 40s were in stark contrast to the lavish murals artists like her husband were creating at the time. Having suffered a crippling bus accident earlier in her teenage life, she began to challenge Mexico's obsession with the female body. Her portraits, purposefully small, addressed a wide range of topics not being addressed by the mainstream art world at the time. These included motherhood, domestic violence, and male egoism.

Her paintings never had subjects wearing lavish jewelry or fancy clothes like those found in muralist paintings. Instead, she would sparsely dress herself up, and when there were accessories, it added that much more importance to them. She would also depict herself in very surreal, unsettling scenarios like in The Two Fridas where she depicts two versions of herself, one with a broken heart and one with a healthy infusing the broken heart with “hopeful” blood., or Henry Ford Hospital where she depicts herself in having an abortion and the struggle she had in real life coming to terms with it.

Although she was the wife of Diego Rivera, her self-portraits stayed rather obscured from the public eye until well after her passing in 1954. Her art has grown in popularity and she is seen by many to be one of the earliest and most influential feminist artists of the 20th century.[70]

Gallery

- José Clemente Orozco, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, Jalisco Governmental Palace, Guadalajara

- José Clemente Orozco, The Trench San Ildefonso College, Mexico City

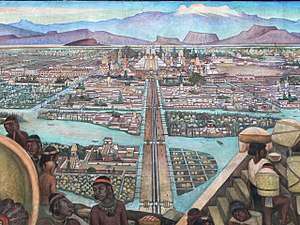

Diego Rivera Tenochtitlan, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City.

Diego Rivera Tenochtitlan, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City. Diego Rivera Mural in the main stairwell of the National Palace

Diego Rivera Mural in the main stairwell of the National Palace David Alfaro Siqueiros, Mural at Tecpan

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Mural at Tecpan- Jean Charlot, Eagle and snake, San Ildefonso College

Selling Mexican art abroad

Despite maintaining an active national art scene, Mexican artists after the muralist period had a difficult time breaking into the international art market. One reason for this is that in the Americas, Mexico City was replaced by New York as the center of the art community, especially for patronage.[71] Within Mexico, government sponsorship of art in the 20th century (dominated until 2000 by the PRI party) meant religious themes and criticism of the government were effectively censored. This was mostly passive, with the government giving grants to artists who conformed to their requirements.[72]

Other Artistic Expressions 1920–1950

The first to break with the nationalistic and political tone of the muralist movement was Rufino Tamayo. For this reason he was first appreciated outside of Mexico.[73] Tamayo was a contemporary to Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco, and trained at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes. Like them he explored Mexican identity in his work after the Mexican Revolution. However, he rejected the political Social Realism popularized by the three other artists and was rejected by the new establishment.[74]

He left for New York in 1926 where success allowed him to exhibit in his native Mexico. His lack of support for the post-Revolutionary government was controversial. Because of this he mostly remained in New York, continuing with his success there and later in Europe. His rivalry with the main three Mexican muralists continued both in Mexico and internationally through the 1950s. Even a belated honorific of “The Fourth Great One” was controversial.[74]

In the 1940s, Wolfgang Paalen published the extremely influential DYN magazine in Mexico City, which focussed on a transitional movement between surrealism to abstract expressionism.

In 1953, Museo Experimental El Eco (in Mexico City) opened; it was created by Mathias Goeritz.

The Rupture Movement

The first major movement after the muralists was the Rupture Movement, which began in the 1950s and 1960s with painters such as José Luis Cuevas, Gilberto Navarro, Rafael Coronel, Alfredo Casaneda, and sculptor Juan Soriano. They rejected social realism and nationalism and incorporated surrealism, visual paradoxes, and elements of Old World painting styles.[69][75] This break meant that later Mexican artists were generally not influenced by muralism or by Mexican folk art.[69]

José Luis Cuevas created self-portraits in which he reconstructed scenes from famous paintings by Spanish artists such as Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Goya, and Picasso. Like Kahlo before him, he drew himself but instead of being centered, his image is often to the side, as an observer. The goal was to emphasize the transformation of received visual culture.[76]

Another important figure during this time period was Swiss-Mexican Gunther Gerzso, but his work was a “hard-edged variant” of Abstract Expressionism, based on clearly defined geometric forms as well as colors, with an effect that makes them look like low relief. His work was a mix of European abstraction and Latin American influences, including Mesoamerican ones.[76][77] In the watercolor field we can distinguish Edgardo Coghlan and Ignacio Barrios who were not aligned to a specific artistic movement but were not less important.

The Olympics in Mexico City (1968); later

"Designed by Mathias Goeritz, a series of sculptures ... [lined] the "Route of Friendship" (Ruta de la Amistad) in celebration of the Olympics ... In contestation to the government-sanctioned artistic exhibition for the Olympics, a group of diverse, independent visual artists organize a counterpresentation entitled Salón Independiente, or Independent Salon; the exhibition signifies a key event in the resistance by artists of state-controlled cultural policies. This show of antigovernment efforts by artists would also be expressed in a mural in support of student movement's protests; the work became known as the Mural Efímero (or Ephemeral Mural)" at UNAM".[78]

The third Independent Salon was staged in 1970. In 1976 "Fernando Gambao spearheads the organization of an exposition of abstract art entitled El Geometrismo Mexicano Una Tendencia Actual".[79]

"In an attempt to reassess ... post-1968 Mexican art, the Museum of Science and Art at UNAM" organized in 2007, the exhibition La Era de la Discrepancia. Arte y cultura visual en México 1968-1997 [80]

In 1990 the exhibition Mexico: Esplendor de Treinta Siglos, started its world tour at Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Neo-expressionism

From the 1960s to the 1980s Neo-expressionist art was represented in Mexico by Manuel Felguerez, Teresa Cito, Alejandro Pinatado, and Jan Hendrix.[75][81]

Swiss-German artist, Mathias Goeritz, in the 1950s created public sculptures including the Torres Satélite in Ciudad Satélite. In the 1960s, he became central to the development of abstract and other modern art along with José Luis Cuevas and Pedro Friedeberg.[82]

Neomexicanismo

In the mid-1980s, the next major movement in Mexico was Neomexicanismo, a slightly surreal, somewhat kitsch and postmodern version of Social Realism that focused on popular culture rather than history.[33] The name neomexicanismo was originally used by critics to belittle the movement. Works were not necessarily murals: they used other mediums such as collage and often parodied and allegorized cultural icons, mass media, religion, and other aspects of Mexican culture. This generation of artists were interested in traditional Mexican values and exploring their roots—often questioning or subverting them. Another common theme was Mexican culture vis-à-vis globalization.[83]

Postmodern

Art from the 1990s to the present is roughly categorized as Postmodern, although this term has been used to describe works created before the 1990s. Major artists associated with this label include Betsabee Romero,[84] Monica Castillo, Francisco Larios,[69] Martha Chapa and Diego Toledo.[75]

The success of Mexican artists is demonstrated by their inclusion in galleries in New York, London, and Zurich.[85]

Art collections and galleries

In 1974 Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil (MACG), a gallery and museum, opened.

Museo Tamayo de Arte Contemporáneo opened in Mexico City in 1981. The National Museum of Art (MUNAL) opened in 1982.

Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo opened in Mexico City in 1986, now defunct. "In 1998 ... with the sudden death of its chief executive, Televisa closed ... [the gallery] for a time, as the turnover in the company coincided with a drastic drop in the company's profitability". [86] [Parts of the] collection have since been exhibited at "different museums, requiring its own space": at Tamayo Museum in 2001, at the Fine Arts Palace Museum[87] ... in 2002; and at MUNAL in 2003.[88]

In 1994, the foundation behind Colección Jumex and its collection of contemporary art, was established; it's located in the industrial outskirts of Mexico City.[89]

Kurimanzutto—a private gallery was founded in 1999.[72]

In 1994 the Olmedo Museum[90] was opened to the public.

In 1996 the Gelman collection was donated to Metropolitan Museum of Art (in New York); part of the Gelmans' collection is on display in the Muros Museum in Cuernavaca.

Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) opened in 2008.

Private art exhibition is concentrated to major urban centers, in particular Monterrey, Nuevo Léon, Guadalajara, Oaxaca City and Puebla.[90]

Art criticism

Octavio Mercado said in 2012 that the activity of art criticism still can be found in specialized magazines and nationally disseminated newspapers; furthermore, a new generation of art critics include Daniela Wolf, Ana Elena Mallet, Gabriella Gómez-Mont, and Pablo Helguera. [91] (Prior to that, claims were made in 2004, that a deficit of native writing about Mexican art, symbolism, and trends, resulted in modern Mexican art shown abroad having been mislabeled or poorly described, as foreign institutions do not sufficiently understand or appreciate the political and social circumstances behind the pieces.[92])

20th century Mexican artists

Some of the most prominent painters in this century are:

- David Alfaro Siqueiros, painter and muralist (Mural in Tecpan (Tlatelolco), Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros)

- Raul Anguiano, harmonic geometry, muralist and printmaker.

- Ignacio Barrios, watercolorist.

- Marta Chapa, oil.

- Mario Orozco Rivera, muralist and easel.

- Joaquín Clausell, oil, Impressionist.

- Miguel Condé, painter, draftsman and figurative recorder.

- Vladimir Cora, painter and sculptor, oil, acrylic and enamel.

- Pedro Coronel, painter, sculptor, draftsman and engraver abstract.

- Rafael Coronel oil, melancholy painting.

- Miguel Covarrubias, Art Deco cartoon.

- José Luis Cuevas, painter, sculptor.

- Claudio Ruanova Self-taught painter.

- Gunther Gerzso, oil, pioneer of Mexican (Abstract Surrealism Expressionism[93]).

- Francisco Goitia, oil

- Jorge González Camarena, painter, sculptor and muralist.

- Saturnino drawing, oil painting, frieze at the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico city.

- María Izquierdo, oil painting, surreal, muralist, first Mexican painter to exhibit in the US.

- Frida Kahlo, oil, surreal.

- Gerardo Murillo Dr. Atl, Oil, (pioneer of "mural" in Mexico). Casino de la Selva

- Leonardo Nierman, painter and sculptor.

- Luis Nishizawa, artist (various techniques).

- Juan O'Gorman, mural (murals at UNAM, Mexico).

- Pablo O'Higgins, American-Mexican (SEP murals and the National School of Agriculture at Chapingo) muralist.

- José Clemente Orozco, mural (murals in the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Hospicio Cabañas).

- José Guadalupe Posada, engraving.

- Alfredo Ramos Martínez, painter and muralist.

- Rivera, painter and muralist (National Preparatory School, Palace of Fine Arts, School of Agriculture at Chapingo).

- Federico Cantú,[94] muralist, printmaker and sculptor.

- Leonora Carrington, painter and novelist of English origin.

- Juan Soriano "The Mozart of Mexican painting."

- Tamayo, oil, mixography, muralist.

- Francisco Toledo, painter, sculptor and ceramist.

- Rodrigo R. Pimentel painter.

- Remedios Varo, surrealist painter.

- Alfredo Zalce, muralist, printmaker and sculptor.

- Roberto Montenegro.

- Gustavo Murueta painter, sculptor, draftsman and printmaker.

- Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin Tlaxcala muralist painter.

- July Ferrá, muralist painter.

The great Mexican muralists of the post-revolution developed, with the paint mural, the concept of "public art", an art to be seen by Ias masses in major public buildings of the time, and could not be bought and transported easily elsewhere, as with easel painting.[95]

21st century

Just like many other parts in the world, Mexico has adopted some modern techniques like with the existence of street artists depicting popular paintings from Mexico throughout history or original content.

Modern Mexican visual artists

Some of the most prominent painters in this century are:

- Eliseo Garza Aguilar, painter and performance artist. Considered among the leading exponents of provocative and thoughtful art of the Third Millennium. In search of a critical response from viewers, combines his paintings in the performances with the theatrical histrionics.

- Emanuel Espintla, painter and performer. Considered among the leading exponents of Mexican naive art and Fridamania.

- Pilar Goutas, a painter who uses oil on amate support, strongly influenced by Pollock and Chinese calligraphy.

- Torres Rafael Correa he settled in Mexico in 2001 and joined the workshop of contemporary art, "The Moth" in Guadalajara, doing various art projects and scenographic. In Mexico works with painters, José Luis Malo, Rafael Sáenz, Edward Enhanced and sculptor Javier Malo. He participated in workshops recorded by the painter Margarita Pointelin. In 2003 he made a formation of Washi Zoo Kei with the Salvadoran master Addis Soriano.

- Enrique Pacheco, sculptor, painter, characterized by merge painting and sculpture with worldwide recognition.

- Pilar Pacheco Méndez, visual artist and sound.[96]

- Daniel Lezama, visual artist. Works on all major formats oil. Born in 1968 to Mexican American parents.

- Roberto Cortazar, visual artist, painter.

- Margarita Orozco Pointelin

- Jazzamoart, visual artist, Guanajuato.

- Rafael Cauduro, painter, sculptor, muralist.

- Arturo Rivera, Painter.

- Germán Montalvo, Painter.

- Omar Rodriguez-Graham, Painter. Born in Mexico City in 1978.

- Vicente Rojo, Painter.

- Sebastian, painter, sculptor.

- Miguel Sanchez Lagrieta, Painter, visual artist.

- Gabriel Orozco, Painter, Sculptor Veracruz.

Popular arts and handcrafts

Mexican handcrafts and folk art, called artesanía in Mexico, is a complex category of items made by hand or in small workshops for utilitarian, decorative, or other purposes. These include ceramics, wall hangings, certain types of paintings, and textiles.[97] Like the more formal arts, artesanía has both indigenous and European roots and is considered a valued part of Mexico’s ethnic heritage.[98]

This linking among the arts and cultural identity was most strongly forged by the country’s political, intellectual, and artistic elite in the first half of the 20th century, after the Mexican Revolution.[98] Artists such as Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo, and Frida Kahlo used artesanía as inspiration for a number of their murals and other works.[98] Unlike the fine arts, artesanía is created by common people and those of indigenous heritage, who learn their craft through formal or informal apprenticeship.[97] The linking of artesanía and Mexican identity continues through television, movies, and tourism promotion.[99]

Most of the artesanía produced in Mexico consists of ordinary things made for daily use. They are considered artistic because they contain decorative details or are painted in bright colors, or both.[97] The bold use of colors in crafts and other constructions extends back to pre-Hispanic times. These were joined by other colors introduced by European and Asian contact, always in bold tones.[100]

Design motifs vary from purely indigenous to mostly European with other elements thrown in. Geometric designs connected to Mexico’s pre-Hispanic past are prevalent, and items made by the country’s remaining purely indigenous communities.[101] Motifs from nature are popular, possibly more so than geometric patterns in both pre-Hispanic and European designs. They are especially prevalent in wall-hangings and ceramics.[102]

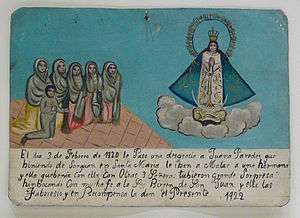

One of the best of Mexico’s handcrafts is Talavera pottery produced in Puebla.[38] It has a mix of Chinese, Arab, Spanish, and indigenous design influences.[103] The best known folk paintings are the ex-voto or retablo votive paintings. These are small commemorative paintings or other artwork created by a believer, honoring the intervention of a saint or other figure. The untrained style of ex-voto painting was appropriated during the mid-20th century by Kahlo, who believed they were the most authentic expression of Latin American art.[104]

Cinema

Cinematography came to Mexico during the Mexican Revolution from the U.S. and France. It was initially used to document the battles of the war. Revolutionary general Pancho Villa himself starred in some silent films. In 2003, HBO broadcast And Starring Pancho Villa as Himself, with Antonio Banderas as Villa; the film focuses on the making of the film The Life of General Villa. Villa consciously used cinema to shape his public image.[106]

The first sound film in Mexico was made in 1931, called Desde Santa. The first Mexican film genre appeared between 1920 and 1940, called ranchero.[107]

While Mexico’s Golden Age of Cinema is regarded as the 1940s and 1950s, two films from the mid to late 1930s, Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936) and Vamanos con Pancho Villa (1935), set the standard of this age thematically, aesthetically, and ideologically. These films featured archetypal star figures and symbols based on broad national mythologies. Some of the mythology according to Carlos Monsiváis, includes the participants in family melodramas, the masculine charros of ranchero films, femme fatales (often played by María Félix and Dolores del Río), the indigenous peoples of Emilio Fernández’s films, and Cantinflas’s peladito (urban miscreant).[108]

Settings were often ranches, the battlefields of the Revolution, and cabarets. Movies about the Mexican Revolution focused on the initial overthrow of the Porfirio Díaz government rather than the fighting among the various factions afterwards. They also tended to focus on rural themes as “Mexican”, even though the population was increasingly urban.[108]

Mexico had two advantages in filmmaking during this period. The first was a generation of talented actors and filmmakers. These included actors such as María Félix, Jorge Negrete, Pedro Armendáriz, Pedro Infante, Cantinflas, and directors such as Emilio “El Indio” Fernandez and cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa. Many of these starts had success in the United States and at the Cannes Film Festival .[107][109] On the corner of La Brea and Hollywood Boulevard, there is a sculpture of four women who represent the four pillars of the cinema industry, one of whom is Mexican actress Dolores del Rio .[107] Gabriel Figueroa is known for black-and-white camerawork that is generally stark and expressionist, with simple but sophisticated camera movement.[110] The second advantage was that Mexico was not heavily involved in the Second World War, and therefore had a greater supply of celluloid for films, then also used for bombs.[107]

_1.jpg)

In the 1930s, the government became interested in the industry in order to promote cultural and political values. Much of the production during the Golden Age was financed with a mix of public and private money, with the government eventually taking a larger role. In 1942 the Banco Cinematográfico financed almost all of the industry, coming under government control by 1947. This gave the government extensive censorship rights through deciding which projects to finance.[108] While the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) censored films in many ways in the 1940s and 1950s, it was not as repressive as other Spanish speaking countries, but it played a strong role in how Mexico’s government and culture was portrayed.[108][110]

The Golden Age ended in the late 1950s, with the 1960s dominated by poorly made imitations of Hollywood westerns and comedies. These films were increasingly shot outdoors and popular films featured stars from lucha libre. Art and experimental film production in Mexico has its roots in the same period, which began to bear fruit in the 1970s.[107][110] Director Paul Leduc surfaced in the 1970s, specializing in films without dialogue. His first major success was with Reed: Insurgent Mexico (1971) followed by a biography of Frida Kahlo called Frida (1984). He is the most consistently political of modern Mexican directors. In the 1990s, he filmed Latino Bar (1991) and Dollar Mambo (1993). His silent films generally have not had commercial success.[110]

In the late 20th century the main proponent of Mexican art cinema was Arturo Ripstein Jr.. His career began with a spaghetti Western-like film called Tiempo de morir in 1965 and who some consider the successor to Luis Buñuel who worked in Mexico in the 1940s. Some of his classic films include El Castillo de la pureza (1973), Lugar sin limites (1977) and La reina de la noche (1994) exploring topics such as family ties and even homosexuality, dealing in cruelty, irony, and tragedy.[110] State censorship was relatively lax in the 1960s and early 1970s, but came back during the latter 1970s and 1980s, monopolizing production and distribution.[107]

Another factor was that many Mexican film making facilities were taken over by Hollywood production companies in the 1980s, crowding out local production.[110] The quality of films was so diminished that for some of these years, Mexico’s Ariel film award was suspended for lack of qualifying candidates.[107] Popular filmmaking decreased but the art sector grew, sometimes producing works outside the view of censors such as Jorge Fons’ 1989 film Rojo Amanecer on the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre. The movie was banned by the government but received support in Mexico and abroad. The film was shown although not widely. It was the beginning of more editorial freedom for filmmakers in Mexico.[110]

Starting in the 1990s, Mexican cinema began to make a comeback, mostly through co-production with foreign interests. One reason for international interest in Mexican cinema was the wild success of the 1992 film Como Agua Para Chocolate (Like Water for Chocolate).[107][110] In 1993, this film was the largest grossing foreign language film in U.S. history and ran in a total of 34 countries.[109] Since then, Mexican film divided into two genres. Those for a more domestic audience tend to be more personal and more ambiguously political such as Pueblo de Madera, La Vida Conjugal, and Angel de fuego. Those geared for international audiences have more stereotypical Mexican images and include Solo con tu Pareja, La Invencion de Cronos along with Como Agua para Chocolate.[109][110]

Mexico’s newest generation of successful directors includes Alejandro González Iñárritu, Guillermo del Toro, and Alfonso Cuarón. Films include Cuarón/Children of Men filmed in England and El Laberinto del Fauno, which was a Mexican/Spanish production. Film professionals in the early 21st century tend to be at least bilingual (Spanish and English) and are better able to participate in the global market for films than their predecessors.[107]

Photography in Mexico

Photography came to Mexico in the form of daguerreotype about six months after its discovery, and it spread quickly. It was initially used for portraits of the wealthy (because of its high cost), and for shooting landscapes and pre-Hispanic ruins.[111] Another relatively common type of early photographic portraits were those of recently deceased children, called little angels, which persisted into the first half of the 20th century. This custom derived from a Catholic tradition of celebrating a dead child’s immediate acceptance into heaven, bypassing purgatory. This photography replaced the practice of making drawings and other depictions of them as this was considered a “happy occasion.”[112] Formal portraits were the most common form of commercial photography through the end of the 19th century.[111]

Modern photography in Mexico did not begin as an art form, but rather as documentation, associated with periodicals and government projects. It dates to the Porfirio Díaz period of rule, or the Porfiriato, from the late 19th century to 1910.[113][114] Porfirian-era photography was heavily inclined toward the presentation of the nation’s modernization to the rest of the world, with Mexico City as its cultural showpiece. This image was European-based with some indigenous elements for distinction.[115]

Stylized images of the indigenous during the Porfirato were principally done by Ybañez y Sora in the costumbrista painting style, which was popular outside of Mexico.[111] The most important Porfirian era photographer was Guillermo Kahlo, who worked with associate Hugo Brehme.[111] Kahlo established his own studio in the first decade of the 1900s and was hired by businesses and the government to document architecture, interiors, landscapes, and factories.[116]