Dolores del Río

| Dolores del Río | |

|---|---|

Dolores del Río in a publicity photo (1933) | |

| Born |

María de los Dolores Asúnsolo y López-Negrete 3 August 1904 Durango, Mexico |

| Died |

11 April 1983 (aged 78) Newport Beach, California, U.S. |

| Resting place |

The Rotunda of Illustrious Persons, Dolores Cemetery Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1925–1978 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Partner(s) | Orson Welles (1940–1943) |

| Relatives |

Ramon Novarro (cousin) Andrea Palma (cousin) Julio Bracho (cousin) |

| Signature | |

| |

Dolores del Río (Spanish pronunciation: [doˈloɾes del rio]; born María de los Dolores Asúnsolo López-Negrete; 3 August 1904[1] – 11 April 1983) was a Mexican actress. She was the first major female Latin American crossover star in Hollywood,[2][3][4][5] with a outstanding career in American films in the 1920s and 1930s. She was also considered one of the more important female figures of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema in the 1940s and 1950s.[6] Del Río is also remembered as one of the most beautiful faces of the cinema in her time.[7] Her long and varied career spanned silent film, sound film, television, stage and radio.

After being discovered in Mexico by the filmmaker Edwin Carewe, she began her film career in 1925. She had roles in a series of successful silent films like What Price Glory? (1926), Resurrection (1927) and Ramona (1928). During this period she came to be considered a sort of feminine version of Rudolph Valentino, a "female Latin Lover".[8]

With the advent of sound, she acted in films that included Bird of Paradise (1932), Flying Down to Rio (1933), Madame Du Barry (1934) and Journey into Fear (1943). In the early 1940s, when her Hollywood career began to decline, del Río returned to Mexico and joined the Mexican film industry, which at that time was at its peak.

When del Río returned to her native country, she became one of the more important promoters and stars of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema. A series of films, including Wild Flower (1943), María Candelaria (1943), Las Abandonadas (1944), Bugambilia (1944) and The Unloved Woman (1949), are considered classic masterpieces and helped boost Mexican cinema worldwide. Del Río remained active in Mexican films throughout the 1950s. She also worked in Argentina and Spain.

In 1960 she returned to Hollywood. During the next years she appeared in Mexican and American films. From the late 1950s until the early 1970s she also successfully ventured into theater in Mexico and appeared in some American television series.

Life and career

1904–1925: Childhood, early marriage and arrival to America

María de los Dolores Asúnsolo y López-Negrete was born in Durango City, Mexico on 3 August 1904.[9]

Her parents were Jesus Leonardo Asúnsolo Jacques, son of wealthy farmers and director of the Bank of Durango, and Antonia López-Negrete, belonging to one of the richest families in the country, whose lineage went back to Spain and the viceregal nobility.[10][11] Antonia was the daughter of Agustín López-Negrete, the hacienda owner who was the first man killed by Doroteo Arango, later known as Pancho Villa.[12]

Her parents were members of the Mexican aristocracy that existed during the Porfiriato (period in the history of Mexico when the dictator Porfirio Díaz was the president). On her mother's side, she was a cousin of the filmmaker Julio Bracho and of actors Ramón Novarro (one of the Latin Lovers of the silent cinema) and Andrea Palma (another actress of the Mexican cinema). On her father's side, she was a cousin of the Mexican sculptor Ignacio Asúnsolo and the social activist María Asúnsolo.[13]

Her family lost all its assets during the Mexican Revolution (1910–1921). Durango aristocratic families were threatened by the insurrection that Pancho Villa was leading in the region. The Asúnsolo family decided to escape. Dolores's father decided to escape to the United States, while she and her mother fled to Mexico City in a train, disguised as peasants.[14]

In 1912, the Asúnsolo family reunited in Mexico City. They had regained their social position and lived under the protection of then-president Francisco I. Madero, who was a cousin of Doña Antonia.[14] For a family of their social status, it was very important that their daughter receive a Catholic education. Dolores attended the College Collège Français de Saint-Joseph,[15] run by French nuns and located in Mexico City. In 1919, her mother took her to a performance of the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, whose interpretation influenced her to become a dancer. She confirmed her decision later when she witnessed the performances of Antonia Mercé "La Argentina". She then persuaded her mother to allow her to take dance lessons with the respected teacher Felipita Lopez. However, she suffered from great insecurity and felt like an "ugly duckling". Her mother commissioned the renowned painter Alfredo Ramos Martínez (famous painter of the Mexican aristocracy) to paint a portrait of her daughter. The portrait helped her overcome her insecurities.[16]

In 1921, aged 16 or 17, Dolores was invited by a group of Mexican women to dance in a party to benefit a local hospital in the Teatro Esperanza Iris. At this party, she met Jaime Martínez del Río y Viñent, son of a wealthy family. Jaime had been educated in England and had spent some time in Europe. After a two-month courtship, the couple wed on 11 April 1921. He was 34 years old; she was not yet 17. Their honeymoon in Europe lasted two years. Jaime maintained close ties with European aristocratic circles. In Spain Dolores danced again in a charity show for wounded soldiers in the battle of Melilla. The monarchs of Spain, Alfonso XIII and Victoria Eugenie, thanked her deeply and the queen gave her a photograph. In 1924, the couple returned to Mexico. They decided to live on Jaime's country estate, where cotton was the main crop. But after the cotton market suffered a precipitous fall, the couple was on the verge of ruin. At the same time Dolores discovered she was pregnant. Unfortunately, she suffered a miscarriage and her doctor informed her that she should never again become pregnant, at risk of losing her life.[17] The couple decided to settle in Mexico City.

In early 1925 Dolores met the American filmmaker Edwin Carewe, an influential director at First National Films, who was in Mexico for the wedding of actors Bert Lytell and Claire Windsor.[18]

Carewe was fascinated by Dolores and managed to be invited to her home by the artist Adolfo Best Maugard. In the evening Dolores danced and her husband accompanied her on the piano. Carewe was determined to have her, so he invited the couple to work in Hollywood. Carewe convinced Jaime, saying he could turn his wife into a movie star, the female equivalent of Rudolph Valentino. Jaime thought that this proposal was a response to their economic needs. In Hollywood, he could fulfill his old dream of writing screen plays.[19] Breaking with all the canons of Mexican society at that time and against their family's wishes, they journeyed by train to the United States.[19]

Acting

1925–1930: Film debut and silent films

Dolores was contracted by Carewe as her agent, manager, producer and director. Her name was shortened to "Dolores Del Rio" (with an incorrect capital "D" in the word "del"). Carewe arranged for wide publicity for her with the intention of transforming her into a star of the order of Rudolph Valentino.[20] As part of an advertising campaign, Carewe made a report dedicated to Dolores in the major magazines in Hollywood:

| “ | Dolores Del Rio, the heiress and First Lady of the High Mexican Society, has come to Hollywood with a cargo of shawls and combs valued at $ 50,000 (is said to be the richest girl in her country thanks to the fortune of her husband and her parents). She will debut in the film Joanna, led by her discoverer Edwin Carewe.[21] | ” |

She made her film debut in Joanna, directed by Carewe in 1925 and released that year. The film was inspired by a famous newspaper series widely accepted among readers and del Río plays the role of Carlotta De Silva, a vamp of Spanish-Brazilian origin, but she appeared for only five minutes.[22]

In 1926, while continuing with his advertising campaign for del Rio, Carewe placed her with the third credit in the film High Steppers, starring Mary Astor. The filmmaker Carl Laemmle was interested in del Río and borrowed her from Carewe to act in the comedy The Whole Town's Talking. These films were not big hits, but helped increase her popularity with the public. Del Rio got her first starring role in the comedy Pals First, also directed by Carewe.[23]

Director Raoul Walsh called del Río to cast her in the war film What Price Glory?. The film was a commercial success, becoming the second highest grossing title of the year, grossing nearly two million dollars in the United States alone.[24] That same year, thanks to the remarkable progress in her career, she was selected as one of the WAMPAS Baby Stars of 1926, along with fellow newcomers Joan Crawford, Mary Astor, Janet Gaynor, Fay Wray and others.[25]

In 1927, Carewe, with the support of the United Artists directed her in Resurrection (1927), based on the novel by Leo Tolstoy. Del Río was selected as the heroine and Rod La Rocque starred as leading man.[26] Due to the success of the film, Fox quickly began shooting The Loves of Carmen (1927), also directed by Raoul Walsh. In 1928, the Fox Film called her to star in the film No Other Woman, directed by Lou Tellegen.[27]

When actress Renée Adorée began to show symptoms of tuberculosis,[28] del Río was selected for the lead role of the MGM film The Trail of '98, directed by Clarence Brown. The film was a huge success and brought favorable reviews from critics. That same year, she was hired by United Artists for the third version of the successful film Ramona, directed by Carewe. The success of the film was helped by the same name musical theme, written by L. Wolfe Gilbert and recorded by del Río with RCA Victor. Ramona was the first United Artists film with a synchronized sound feature, but was not a talking picture.[29]

In late 1928, Hollywood was concerned with the impending arrival of sound films. On 29 March, at Mary Pickford's bungalow, United Artists brought together Pickford, del Río, Douglas Fairbanks, Charles Chaplin, Norma Talmadge, Gloria Swanson, John Barrymore, and D. W. Griffith to speak on the radio show The Dodge Brothers Hour to prove they could meet the challenge of talking movies. Del Río surprised the audience by singing "Ramona".[30]

Although her career blossomed, her personal life was turbulent. Her marriage with Jaime Martínez ended in 1928. The differences between the couple emerged after settling in Hollywood. In Mexico City, she had been the wife of Jaime Martinez del Rio, but in Hollywood Jaime became husband of Dolores del Rio, a movie star. The trauma of a miscarriage added to the marital difficulties and del Río was advised not to have children. After a brief separation, Dolores filed for divorce. Six months later, she received news that Jaime had died in Germany.[31] As if this were not enough, Del Río had to suffer incessant harassment from her discoverer, Edwin Carewe, who did not cease in his attempt to conquer her.[32]

In late 1928, she made her third film with Raoul Walsh, The Red Dance. Her next project was Evangeline (1929) a new production of United Artists also directed by Carewe and inspired by the epic poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The film was accompanied by a theme song written by Al Jolson and Billy Rose and played by del Río. Like Ramona, the film was released with a Vitaphone disc selection of dialogue, music and sound effects.[33]

Edwin Carewe had ambitions to marry del Río, with the intent that they become a famous Hollywood couple. Carewe prepared his divorce from his wife Mary Atkin and seeded false rumors in campaigns of his films. But during the filming of Evangeline, United Artists convinced del Río to separate herself artistically and professionally from Carewe, who still held an exclusive contract with the actress.[34]

In New York, following the successful premiere of Evangeline, del Río declared to the reporters: Mr. Carewe and I are just friends and companions in the art of the cinema. I will not marry Mr. Carewe.[35] Eventually, she canceled her contract with him. Furious, Carewe filed criminal charges against Dolores. Advised by United Artists lawyers, Dolores reached an agreement with Carewe out of court. In spite of this settlement, Carewe started a campaign against her. In order to eclipse her, he filmed a new sound version of Resurrection starring Lupe Velez, another popular Mexican film star and alleged rival of Del Río.[36]

Having finally broken off professionally from Carewe, del Río was prepared for the filming of her first talkie: The Bad One, directed by George Fitzmaurice. The film was released in June 1930 with great success. Critics said that del Río could speak and sing in English with a charming accent. She was a suitable star for the talkies.[37]

1930–1942: American cinematography, marriage to Cedric Gibbons and Orson Welles

In 1930, del Río met Cedric Gibbons, artistic director of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, at a party at Hearst Castle whom was also one of the most influential men in Hollywood. The couple started a romance and finally married on August 6, 1930.[38] The Del Rio-Gibbons were one of the most famous couples of Hollywood in the early thirties. They organized famous 'Sunday brunches' in their fabulous Art Deco mansion, considered one of the most modern and elegant in the high circles of Hollywood.[39] Shortly after her marriage, Del Río fell seriously ill with a severe kidney infection. The doctors recommended long bed rest.[40] When she regained her health, she was hired exclusively by RKO Pictures. Her first film with the studio was Girl of the Rio (1931), directed by Herbert Brenon.

In 1932, producer David O. Selznick called the filmmaker King Vidor and said: "I want del Río and Joel McCrea in a love story in the South Seas. I didn’t have much of a story for the film, but be sure that it ends with the young beauty jumping into a volcano.".[41] Bird of Paradise was shot in Hawaii and del Río became a beautiful native. The film premiered on 13 September 1932 in New York earning rave reviews. Bird of Paradise created a scandal when released due to a scene featuring del Río and McCrea swimming naked. This film was made before the Production Code was strictly enforced, so some degree of nudity in American movies was still fairly common.[42][43]

As RKO got the result they expected, they quickly decided that del Rio do another film, a musical comedy directed by Thornton Freeland: Flying Down to Rio (1933). In the film Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers first appeared as dance partners.[41] It featured del Río opposite Fred Astaire in an intricate dance number called Orchids in the Moonlight. But after the premiere, RKO were worried about their economic problems and decided not to renew del Río's contract.[44]

In 1934 Jack Warner met del Río at a party and offered her a starring role in two films for Warner.[45] The first was the musical comedy Wonder Bar, directed by Lloyd Bacon. Busby Berkeley was the choreographer and Al Jolson her co-star. Del Río and Jolson were gradually stealing the show. Del Río's character grew, while the character of Kay Francis, the other female star of the film, was reduced. The film was released in March 1934 and was a huge blockbuster for Warners.[46]

Warner began filming Madame Du Barry with del Río as star and William Dieterle as director. Dieterle focused on her beauty with the help of an extraordinary cloakroom designed by Orry Kelly (considered one of the most beautiful and expensive at the time).[47] But Madame Du Barry was a major cause of dispute between the studio and the Hays Code office, primarily because it presented the court of Louis XV as a sex farce centered around del Rio.[41] The film was severely mutilated by censorship and did not get the expected success.[48]

In the same year, del Río, along with other Mexican film stars in Hollywood (like Ramón Novarro and Lupe Vélez), was accused of promoting Communism in California. This happened after the mentioned film stars attended a special screening of the Sergei Eisenstein's film ¡Que Viva México!, copies of which were claimed to have been edited by Joseph Stalin,[49] and a film which promoted nationalist sentiment with socialist overtones.

.jpg)

In 1935 Warner called her again to star in another musical comedy called In Caliente (1935), where she plays a sultry Mexican dancer who has an affair with the character played by Pat O'Brien. In the same year she starred in I Live for Love, with Busby Berkeley as a director. This time there were dance numbers and Berkeley focused on her glamour with a sophisticated wardrobe. The last film she made with Warners was The Widow from Monte Carlo (1936), which went unnoticed.[50]

In 1937, with the support of Universal Studios, del Río filmed The Devil's Playground opposite Chester Morris and Richard Dix. However, despite the popularity of the three stars, the film was a failure. In 1938, she signed a contract with 20th Century Fox to star in two films with George Sanders. In both films (Lancer Spy and International Settlement), del Río plays the role of a seductive spy. But both films were box-office failure.[51]

Cedric Gibbons used his influence with MGM and gained for del Río the main female role in the film The Man from Dakota (1940). But despite his position at the studio, Gibbons could never help his wife in his place of work, where the leading figures were Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford and Jean Harlow. Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg both admired del Río's beauty, but her career did not interest them.[52]

She was put on a list entitled "box office poison", (along with stars like Crawford, Garbo, Katharine Hepburn, Marlene Dietrich, Mae West, Fred Astaire, and others). The list was submitted to Los Angeles newspapers by an independent movie theater whose point was that these stars' high salaries and public popularity did not counteract the low ticket sales for their movies.[53]

Amid the decline of her career, in 1940 Dolores met actor and filmmaker Orson Welles in a party organized by Darryl Zanuck. The couple felt a mutual attraction and began a discreet affair, which caused the divorce of del Río and Gibbons.[54] While looking for ways to resume her career, she accompanied Orson Welles in his shows across the United States, radio programs and shows at the Mercury Theatre.[55] She was at his side during filming and controversy of his masterpiece: Citizen Kane. The film, considered a masterpiece today, caused a media scandal by performing open criticism against the magnate William Randolph Hearst, who began to boycott Welles' projects.[56]

At the beginning of 1942, she began work on Journey into Fear with Norman Foster as director and Welles as producer. Nelson Rockefeller, in charge of the Good Neighbor policy (and also associated with RKO through his family investments), hired Welles to visit South America as an ambassador of good will to counter fascist propaganda about Americans. Welles left the film four days later and traveled to Rio de Janeiro on his goodwill tour. Welles went crazy with the carnival in Rio de Janeiro, becoming promiscuous and the news came soon to the United States. She decided to end the relationship, through a telegram that he never answered.[57] That same year, her father died in Mexico. Amid these personal and professional crises, she decided to return to Mexico, commenting:

| “ | Divorced again, without the figure of my father. A film where I barely appeared, and one where they were really showing me the way of the art. I wanted to go the way of the art. Stop being a star and become an actress, and that I could only do in Mexico. I wish to choose my own stories, my own director, and camera man. I can accomplish this better in Mexico. I wanted to return to Mexico, a country that was mine and I did not know. I felt the need to return to my country.[58] | ” |

1943–1959: Mexican films

Since the late 1930s, she was sought by Mexican film directors, but economic circumstances were not favorable for the entry of del Río to the Mexican cinema.[59] She was a friend of noted Mexican artist (such as Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo), and maintained ties with Mexican society and cinema. After breaking off her relationship with Welles, del Río returned to Mexico.[60]

As soon as she returned to her country, Mexican director Emilio "El Indio" Fernández invited her to film Flor silvestre (1943). Fernandez was her great admirer and he was eager to direct her. This was del Río's first Spanish-language film. The film gathers a successful film crew consisting of Fernandez, the photographer Gabriel Figueroa, the screenwriter Mauricio Magdaleno and Dolores and Pedro Armendariz as the stars. Subsequently, they filmed Maria Candelaria, the first Mexican film to be screened at the Cannes International Film Festival where it won the Grand Prix (now known as the Palme d'Or) becoming the first Latin American film to do so.[61] Fernández has said that he wrote an original version of the plot on 13 napkins while sitting in a restaurant. He was anxious because he was in love with del Río and could not afford to buy her a birthday present.[62]

Her third film with Fernández Las Abandonadas (1944), was a controversial film where del Río plays a woman who gives up her son and falls into the world of prostitution. She won the Silver Ariel (Mexican Academy Award) as best actress for her role in the film. Bugambilia (1944) was her fourth movie directed by Fernández. As del Rio did not correspond to the director's love advances, Bugambilia filming became a torture for both and for the rest of the team, who had to endure the mood swings of the director and the constant threats of del Río leaving the film. When the film was completed in January 1945, del Río announced that she would never again work with "El Indio" Fernández.[63]

In 1945, del Río filmed La selva de fuego directed by Fernando de Fuentes. The script of this film came to her in error, because of a confused messaging. The film had been specially created for María Félix, another popular Mexican movie star at that time. Félix meanwhile, received the script for Dizziness, a film originally created for del Rio. When the two stars realized the mistake they refused to return the scripts. Del Río was fascinated by playing a different character which also performed daring scenes with Arturo de Córdova. From this time the press began speculating a strong rivalry between del Río and Felix.[64]

In 1946 del Río worked for the first time under Roberto Gavaldón's direction in La Otra (1946), a successful film where del Río plays a twin sister (the film inspired years later the movie Dead Ringer, starred by Bette Davis in 1964).[65]

In 1947 she was invited by the film director John Ford to film The Fugitive (an adaptation of the novel The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene)[66] alongside Henry Fonda. Emilio Fernández also served as associate producer and Gabriel Figueroa as a photographer. The movie was filmed in Mexico. In the film del Río plays an indigenous woman in love with a priest played by Fonda.[67] The popularity of del Río spread throughout Latin America. In the same year she travels to Argentina to film Historia de una mala mujer, a film adaptation of the Oscar Wilde's Lady Windermere's Fan, directed by Luis Saslavsky. Dolores remained a long time in Argentina, and returning to Mexico in early 1948, had to face the attacks of the press, who accused her of having been part of the Ford film, unfairly classified as a communist.[68]

In 1949, del Río accept worked again with Emilio Fernández and her film team in the film La Malquerida. The film is based on the novel of the Spanish writer Jacinto Benavente. Del Río won critical acclaim for her portrayal of Raymunda, a woman confronted with her own daughter for the love of a man. The role of her daughter was played by actress Columba Dominguez, the new film muse of Emilio Fernandez.[69] In 1950, del Río was directed again by Roberto Gavaldón in two films: La casa chica and Deseada. In the first she played the role of the mistress of a respectable doctor. The film also shows a series of murals of Diego Rivera in which del Río appears embodied, as well as a sculpture of the actress made for the film by the artist Francisco Zúñiga.[70] Deseada is based in Xtabay, an argument of the writer Antonio Mediz Bolio. Her partner was the Spanish heartthrob Jorge Mistral and the film was framed as archaeological beauties of Yucatán.[71] That same year, del Río's cousin, activist Maria Asúnsolo, asked her to sign a document for a "conference for the world peace".[71]

On this year she also met the American millionaire Lewis A. Riley in Acapulco. Riley was known in the middle of Hollywood cinema in the forties for being a member of the Hollywood Canteen, an organization created by movie stars to support relief efforts in World War II. At that time Riley lived a torrid affair with Bette Davis.[72] Del Rio and Riley started a long romance.

In 1951, del Río starred in Doña Perfecta, based on the novel by Benito Perez Galdos. For this work she won her second Silver Ariel Award for Best Actress. In 1953 Gavaldón directed her again in the film El Niño y la Niebla (1953). Her portrayal of an overprotective mother with a mental instability attracted critical acclaim and she was honored with her third Silver Ariel Award.[73] In 1952, del Río joined the radio drama El derecho de nacer, based on the same name novel of the Cuban novelist Felix B. Caignet.[74]

In 1954, del Río was slated to appear as the wife of Spencer Tracy's character in the 20th Century Fox film Broken Lance. The U.S. government denied her permission to work in the United States, accusing her of being sympathetic to international Communism. The document signed by her cheering for world peace, as well as her links with figures openly communist (as Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo) and her past relationship with Orson Welles, had been interpreted in the United States as sympathy for the communism.[75] She was replaced in the film by Katy Jurado. She reacted by sending a letter to the U.S. government, stating:

| “ | "I believe that after all this, I have nothing [for which] to reproach myself. I'm a woman who only wants to live in peace with God and with men."[73] | ” |

While her situation was solved in the United States, del Río accepted the proposal of filming in Spain another adaptation of a novel by Benavente, Señora Ama, directed by her cousin, the filmmaker Julio Bracho. Unfortunately the prevailing censorship in the Spanish cinema caused the film was seriously wounded during the editing.[76]

In 1956, her political situation in the United States was resolved. She began to listen with interest to theatrical offerings. Del Río was already thinking that the play Anastacia of Marcelle Maurette, would be a good choice for her debut. [77] To prepare for this new facet of her career, she engaged the services of Stella Adler as her acting coach. Del Río debuted successfully at the theater on the Falmouth Playhouse in Massachusetts on July 6, 1956 and to continue with a tour of seven other theaters throughout New England.[78][79] She took advantage of her return to the United States and granted an interview to Louella Parsons to make clear her political position: "In Mexico we are worried and fighting against communism."[80]

In 1957 she was selected as vice president of the jury of the 1957 Cannes Film Festival. She was the first woman to sit on the jury.[81]

In 1959, Mexican filmmaker Ismael Rodríguez brought del Río and María Félix together in the film La Cucaracha. The meeting of the two actresses, considered the main female stars of Mexican cinema, was a success at the box office.

This same year, she married Lewis Riley in New York after ten years of relationship. They remained together until her death in 1983.[82]

1960–1978: Theater, television and final films

In 1957, she debuted in television in the role of a Spanish lady in the American television series Schlitz Playhouse of Stars, opposite Cesar Romero. The next year she appeared in an episode of The United States Steel Hour.

.jpg)

Del Río and her husband founded their own production company called Producciones Visuales.[83] and they produced together numerous theater projects for the showcase of del Río. Mexican writer Salvador Novo became the translator of her plays. Her first production in Mexico City was Oscar Wilde's Lady Windermere's Fan, which she had made as a film in Argentina several years earlier. She toured Mexico in the play, an enterprise that was both financially and critically successful, and she later took it to Buenos Aires.[84]

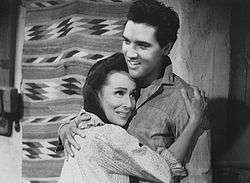

In 1960, del Río returned to Hollywood after 18 years. She was hired by Fox to play the role of mother of Elvis Presley's character in the film Flaming Star, directed by Don Siegel.

In 1964, she appeared in John Ford's Cheyenne Autumn.[85] In 1966, the actress returned to Spain, where she filmed the movie La Dama del Alba, directed by Francisco Rovira Beleta. The next year, she filmed her last Mexican film, Casa de Mujeres. In the same year, the Italian filmmaker Francesco Rosi invited her to be part of the movie More Than a Miracle with Sophia Loren and Omar Sharif. She played Sharif's character's mother.

Others of her successful theater projects were The Road to Rome (1958), Ghosts (1962), Dear Liar: A Comedy of Letters (1963), La Voyante (1964), The Queen and the Rebels (1967)[86] and The Lady of the Camellias (1968).[87]

She also appeared in the TV shows The Dinah Shore Chevy Show (1960), the TV movie The Man Who Bought Paradise (1965), I Spy and Branded (1966). In 1968, del Río first performed on Mexican television in an autobiographical documentary narrated by her. Her last appearance on television was in a 1970 episode of Marcus Welby, M.D..[88]

In 1978, she appeared in The Children of Sanchez, directed by Hall Bartlett and starring Anthony Quinn. She made a brief appearance playing the grandmother. This was her last film appearance.[66]

Later years

In the late 1950s, she became a main promoter of the Acapulco International Film Review, serving as host on numerous occasions.[89] In 1966, del Río was co-founder of the Society for the Protection of the Artistic Treasures of Mexico with the philanthropist Felipe García Beraza. The society was responsible for protecting buildings, paintings and other works of art and culture in México.[90]

On January 8, 1970, she, in collaboration with other renowned Mexican actresses, founded the union group "Rosa Mexicano", which provided a day nursery for the children of the members of the Mexican Actor's Guild. Del Río was responsible for various activities to raise funds for the project and she trained in modern teaching techniques.[91] She served as the president from its founding until 1981. After her death, the day nursery adopted the official name of Estancia Infantil Dolores del Río (The Dolores del Río Day Nursery), and today remains in existence.[92]

In 1972, she helped found the Cultural Festival Cervantino in Guanajuato. Her deteriorating health led her to cancel two television projects in 1975. The American television series Who'll See the Children? and Mexican telenovela Ven Amigo. In her work in supporting children she became a spokeswoman of the UNICEF in Latin America and records a series of television commercials for the organization.[93] In 1976 she served as president of the jury in the San Sebastian Film Festival.[94]

In 1978 the Mexican American Institute of Cultural Relations and the White House gave Dolores a diploma and a silver plaque for her work in cinema as a cultural ambassador of Mexico in the United States. During the ceremony she was remembered as a victim of McCarthyism.[95]

At the age of 76 del Río appeared on the stage of the Palace of Fine Arts theater the evening of October 11, 1981 for a tribute at the 25th San Francisco International Film Festival.[96] During the ceremony, filmmakers Francis Ford Coppola, Mervyn LeRoy and George Cukor spoke, with Cukor declaring del Rio the "First Lady of American Cinema".[97] This was her last known public appearance.[98] In 1982, she was awarded the George Eastman Award, given by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film.[99]

Personal life

Regardless of their marriages at different times in her life, she was romantically linked with actor Errol Flynn,[100] filmmaker John Farrow,[101] writer Erich Maria Remarque, film producer Archibaldo Burns, and actor Tito Junco.[102]

Her relationship with Orson Welles (1939-1943) ended after four years largely due to his infidelities. Rebecca Welles, the daughter of Welles and Rita Hayworth, expressed her desire to travel to Mexico to meet Dolores. In 1954, Dolores received her at her home in Acapulco. After their meeting, Rebecca said: My father considered Dolores the great love of his life. She is a living legend in the history of my family. According to Rebecca, until the end of his life, Welles felt for del Río, a kind of obsession.[103]

Mexican filmmaker Emilio Fernández was one her admirers. He said that he had appeared as an extra in several films of Dolores in Hollywood just to be near her. The beauty and elegance of del Río had impressed him deeply. Fernández said: I fell in love with her, but she always ignored me. I adored her... really I adored her.[104]

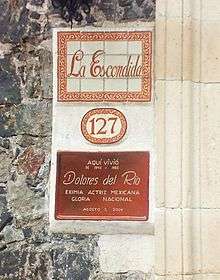

The house of the del Río at Coyoacán called "La Escondida" and also spent their days in Acapulco, both homes became a meeting point for personalities like Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, María Felix, Merle Oberon, John Wayne, Edgar Neville, Begum Om Habibeh Aga Khan, Nelson Rockefeller, the Duke of Windsor and Wallis Simpson, Princess Soraya of Iran and more.[82]

There are many anecdotes about her rivalry with Lupe Vélez. Dolores never understood the quarrel that Vélez kept with her. Dolores inquired to meet her because it hurt to be ridiculed by the Mexican Spitfire . But the prestige of Dolores was known and respected, and Vélez could not ignore this. Vélez wore spectacular costumes, but never reached the del Río's supreme elegance. Velez was popular, had many friends and surrendered fans, but never attended the social circle in Hollywood, where del Río was accepted without reservations. Vélez spoke ill of del Río, but she never mentioned her name in an offensive way. Vélez evidently resented Dolores' success during the years in which both met in Hollywood.[105]

There was media speculation about a strong rivalry between Dolores and María Félix, another diva of the Mexican Cinema.[106] Félix said in her autobiography: "With Dolores I don't have any rivalry. On the contrary. We were friends and we always treated each other with great respect. We were completely different. She [was] refined, interesting, soft on the deal, and I'm more energetic, arrogant and bossy".[107] Félix said in another interview: "Dolores del Río was a great lady. She behaved like a princess. A very intelligent and very funny woman. I appreciate her very much and I have great memories of her".[108]

After her death, actor Vincent Price used to sign his autographs as "Dolores del Río". When asked why, the actor replied: "I promised Dolores on her deathbed that I would not let people forget about her."[109]

Death

In 1978, she was diagnosed with osteomyelitis, and in 1981 she was diagnosed with Hepatitis B following a contaminated injection of vitamins.[82] She also suffered of arthritis.[82] In 1982, del Río was admitted to Scripps Hospital, La Jolla, California, where hepatitis led to cirrhosis.[110]

On 11 April 1983, Dolores del Río died from liver failure at the age of 78, in Newport Beach, California.[111] It is said that the day she died, an invitation to attend the Oscars was sent to her.[82][110] After dying, she was cremated and her ashes were moved from the United States to Mexico where they were interred at the Dolores Cemetery in Mexico City, Mexico,[82] specifically on The Rotunda of Illustrious Persons.[112]

Image

Dolores del Río always projected a special elegance with her beauty, more than just a Latin Bombshell such as another actresses like Lupe Velez. Del Rio's intrinsic elegance was apparent even offscreen.[113] Del Río strongly identified with her Mexican heritage despite her growing fame and her transition to "modernity." She also felt strongly about being able to play Mexican roles and bemoaned the fact that she was not cast in them. She never relinquished her Mexican citizenship and said in 1929 (at the height of her popularity) that she wanted "to play a Mexican woman and show what life in Mexico really is. No one has shown the artistic side –nor the social".[114]

Dolores del Río was considered one of the prototypes of female beauty in the 1930s. In 1933, the American film magazine Photoplay conducted a search for "the most perfect female figure in Hollywood", using the criteria of doctors, artists and designers as judges. The "unanimous choice" of these selective arbiters of female beauty was del Río. The question posed by the search for the magazine and the methodology used to find "the most perfect female figure" reveal a series of parameters that define femininity and feminine beauty at that particular moment in the US history.[115][116] Larry Carr (author of the book More Fabulous Faces) said del Río's appearance in the early 1930s influenced Hollywood. Women imitated her style of dress and makeup. A new kind of beauty occurs, and Dolores del Río, was the forerunner.[117] She is also considered the pioneer of the two piece swimsuit.[82]

According to filmmaker Josef von Sternberg, stars such as del Río, Marlene Dietrich, Carole Lombard and Rita Hayworth helped him to define his concept of the glamour in Hollywood.[118]

When del Río returned to Mexico, she radically changed her image. In Hollywood, she had lost ground to the modernity of the faces. In Mexico, she had the enormous fortune that the filmmaker Emilio Fernandez emphasized Mexican indigenous features. She did not come to Mexico as the "Latina bombshell from Hollywood," transforming her makeup to highlight her indigenous features. Del Río defined the change that her appearance suffered in her native country: "I took off my furs and diamonds, satin shoes and pearl necklaces; all swapped by the shawl and bare feet."[119]

Joan Crawford said, on a visit to Mexico in 1963,

Dolores became, and remains, as one of the most beautiful stars in the world.[120]

Marlene Dietrich said of del Río,

Dolores del Río was the most beautiful woman who ever set foot in Hollywood.[121][122][123]

George Bernard Shaw once said,

The two most beautiful things in the world are the Taj Mahal and Dolores del Río.[124]

Fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli said,

I have seen many beautiful women in here, but none as complete as Dolores del Río![125]

Diego Rivera said,

The most beautiful, the most gorgeous of the west, east, north and south. I'm in love with her as 40 million Mexicans and 120 million Americans that can't be wrong.[126]

Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes said,

Garbo and Dietrich were women turned into goddesses. Del Rio was a goddess about being a woman.[127]

Photographer Jerome Zerbe said,

Dolores del Río and Marlene Dietrich are the most beautiful women I've ever photographed.[128]

The fashion designer Orry-Kelly reminisced about the first time he dressed del Rio,

I draped her naked body in jersey. She wanted no underpinnings to spoil the line. When I finished draping her she became a Greek goddess as she walked close to the mirror and said, it is beautiful. Gazing into the mirror she said in a half-whisper, Jesus, I am beautiful. Narcissistic? Probably yes, but she was right. She looked beautiful.[129]

German writer Erich Maria Remarque, who compared her beauty with Greta Garbo, described that a perfect woman would be a merger between the two actresses.[130]

When she appeared swimming naked in Bird of Paradise, Orson Welles said that del Río represented the highest erotic ideal with her performance in the film.[43]

In 1952, she was awarded the Neiman Marcus Fashion Award, and was called "The best-dressed woman in America."[131]

In art and literature

Del Río was painted by important Mexican artists such as Diego Rivera, Miguel Covarrubias and José Clemente Orozco.[132]

Poet Salvador Novo wrote her a sonnet and translated all her stage plays. She inspired Jaime Torres Bodet's novel La Estrella de Día (Star of the Day), published in 1933, which chronicles the life of an actress named Piedad. Vicente Leñero was inspired by del Río to write his book, Señora. Carlos Pellicer also wrote her a poem in 1967.[133] In 1982, del Río and Maria Félix were parodied in the novel Orchids in the Moonlight: Mexican Comedy by Carlos Fuentes .[134]

Rosa Rolanda also made a portrait of her in 1938.[135] In 1941, she was painted by Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco. Other artists were reflected her in their works were Miguel Covarrubias,[136] John Carroll[97] and Adolfo Best Maugard.[137]

In 1970, the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura, the Mexico's Screen Actors Guild, the Humane Society of the Artistic Treasures of Mexico and the Motion Picture Export Association of America paid her a tribute titled Dolores del Rio in the Art in which her main portraits and a sculpture by Francisco Zúñiga were exhibited.[138]

Del Río was the model of the statue of Evangeline, the heroine of Longfellow's romantic poem located in St. Martinville, Louisiana. The statue was donated by del Río, who played Evangeline in the 1929 film.[139]

In her will, del Río stipulated that all her artworks were donated to the National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature of Mexico, for display in various museums in Mexico City, including the National Museum of Art, the Museum of Art Carillo Gil and the Home-Studio of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.[140]

Legacy and memorials

—Del Río commenting about her role as a Mexican woman in Hollywood.

Del Río was the first Mexican actress to succeed in Hollywood. The others have been Lupe Velez, Katy Jurado, and in recent years Salma Hayek[143] and Lupita Nyong'o.[144] Her career had a great impact on the trajectories of the Latinas in Hollywood who followed her. Stars like Salma Hayek, Jennifer Lopez, Eva Mendes and Penelope Cruz follow the steps forged by Dolores del Rio.

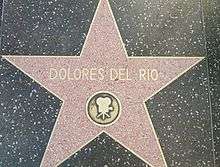

- She has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1630 Vine Street in recognition of her contributions to the motion picture industry.

- Dolores del Río also has a statue at Hollywood-La Brea Boulevard in Los Angeles, designed by Catherine Hardwicke built to honor the multi-ethnic leading ladies of the cinema together with Mae West, Dorothy Dandridge and Anna May Wong.

- Del Río has also a mural painted on the east side of Hudson Avenue just north of Hollywood Boulevard painted by the Mexican-American artist Alfredo de Batuc.[145]

- Del Río is one of the entertainers displayed in the mural "Portrait of Hollywood", designed in 2002 by the artist Eloy Torrez in the Hollywood High School.[146][147]

- Del Río's memory is honored in three monuments in Mexico City. The first is a statue located in the second section of Chapultepec Park.[148] The other two are busts. One is located in the Parque Hundido.[149] and the other is in the nursery that bears her name.

- In Durango, Mexico, her hometown, an avenue is named after her, Blvd. Dolores del Río.[150]

- Chester Gould, the creator of Dick Tracy, took Dolores del Río as inspiration to create Texie Garcia, one of Tracy's main enemies.

- She appeared in vintage footage in the Woody Allen's film Zelig (1983).[151]

- Since 1983, the society Periodistas Cinematográficos de México (Mexican Film Journalists) (PECIME) has been giving the Diosa de Plata (Dolores del Río) Award for the best dramatic female performance.

- In 2005, on what was believed to be the centenary of her birth (she was actually born in 1904), her remains were moved to the Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres in Mexico City.[153]

- On 3 August 2017, the 113th anniversary of her birth, Google released a Google Doodle created by Google artist Sophie Diao honoring Del Río.[154]

After her death, her photo archive was given to the Center for the Study of History of Mexico CARSO by Lewis Riley.

Selected filmography

- Joanna (1925)

- What Price Glory? (1926)

- Resurrection (1927)

- The Loves of Carmen (1927)

- Ramona (1928)

- Evangeline (1929)

- Bird of Paradise (1932)

- Flying Down to Rio (1933)

- Wonder Bar (1934)

- Madame Du Barry (1934)

- In Caliente (1935)

- Journey Into Fear (1943)

- Wild Flower (1943)

- María Candelaria (1943)

- Las Abandonadas (1944)

- Bugambilia (1944)

- La Otra (1946)

- The Fugitive (1947)

- The Unloved Woman (1949)

- Doña Perfecta (1951)

- El Niño y la niebla (1953)

- La Cucaracha (1959)

- Flaming Star (1960)

- Cheyenne Autumn (1964)

- More Than a Miracle (1967)

- The Children of Sanchez (1978)

Notes

- ↑ this (see 1919 travel manifest at Ancestry.com (subscription required)) gives her age as 15; accessed 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Hall, Linda (2013). Dolores del Río: Beauty in Light and Shade. Stanford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780804786218. Film International: The First Latina to Conquer Hollywood Archived 2014-06-25 at the Wayback Machine., Filmint.nu; accessed July 19, 2016.

- ↑ The Face of Deco: Dolores Del Rio Archived 2016-01-07 at the Wayback Machine., Screendeco.wordpress.com, May 18, 2012.

- ↑ Terán, Luis (1999). "Katy Jurado: A Proudly Mexican Hollywood Star". SOMOS: 84, 85.

- ↑ Dolores del Río biodata Archived 2015-07-26 at the Wayback Machine., TCM.com; accessed July 19, 2016.

- ↑ Zolov, Eric (2015). Iconic Mexico: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo. New York: ABC-CLIO,. p. 260. ISBN 9781610690447. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Overview for Dolores Del Rio". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 2015-07-26.

- ↑ Hall (2013), pp. 2, 15

- ↑ Latina/o stars in U.S. eyes: the making and meanings of film and TV stardom. Books.google.co.uk. 2009. ISBN 9780252076510. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ Ramón, David (1997). Dolores del Río vol. 1 :Un cuento de hadas. México: Editorial Clío. p. 10. ISBN 968-6932-36-4.

- ↑ Torres, José Alejandro (2004). Los Grandes Mexicanos: Dolores del Río (in Spanish). México: Grupo Editorial Tomo, S.A. de C.V. p. 11. ISBN 978-9706669971.

- ↑ "Mexican Revolution of 1910". latinoartcommunity.org. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ "Asúnsolo Morán, María". Enciclopediagro.org. 24 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- 1 2 Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 11.

- ↑ colegio francés

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 12.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Franco Dunn, Cinta (2003). Grandes Mexicanos Ilustres: Dolores del Río (Great Illustrious Mexicans: Dolores del Río). México: Promo Libro. p. 11. ISBN 84-492-0329-5.

- 1 2 Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 16.

- ↑ "Dolores del Río". cinemexicano.mty.itesm.mx. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015.

- ↑ Torres (2004), pg. 22

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 25

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 26

- ↑ Franco Dunn (2003), pg. 24

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 27

- ↑ Ramón 1997, vol. 1, pg. 28

- ↑ "No Other Woman (1928)". IMDb. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ Ramón 1997, vol. 1, pg. 33

- ↑ "Ramona (1928) Trivia". IMDb. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 34

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1 pp. 36-37

- ↑ Evangeline (Broadway at the Park Theatre) Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine., IBDb.com; accessed 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 36

- ↑ Torres (2004), pg. 32

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 46

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 39

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pp. 43-45

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, p. 56

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 46

- 1 2 3 Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 47

- ↑ Sex in Cinema Archived 22 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Dolores Del Rio: Bird of Paradise (1932)". 12 May 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- ↑ filmint.nu

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 48

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 49

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 54

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pp. 53–54

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pp. 51–52

- ↑ Ramón (1997),vol. 1, pp. 54–55

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pp. 54–55

- ↑ Monsivais, Carlos (1995). "Dolores del Río: El Rostro del Cine Mexicano (Dolores del Río: The Face of the Mexican Cinema)". SOMOS: 35.

- ↑ "Dolores del Rio in Hollywood". Austinfilm.org. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 57

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 61

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 59

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 61

- ↑ Ramón 1997, vol. 1, pg. 61

- ↑ Ramón, David (1997). Dolores del Río vol. 2 :Volver al origen. México: Editorial Clío. p. 10. ISBN 968-6932-37-2.

- ↑ "Curiosidades de Dolores del Río". Mexico.mx (in Spanish). 6 April 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ↑ Festival de Cannes – Official Selection 1946 Archived 3 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Tuñón, Julia (2003). The Cinema of Latin America. Wallflower Press. pp. 45–46.

- ↑ "Bugambilia (1944)". cinemexicano.mty.itesm.mx. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016.

- ↑ Félix, María (1994). Todas mis Guerras. Clío. p. 84. ISBN 9686932089.

- ↑ Chandler, Charlotte (2006). The Girl Who Walked Home Alone: Bette Davis, A Personal Biography. Simon and Schuster. p. 324. ISBN 9780743289054.

- 1 2 Dolores del Río on IMDb

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pg. 28

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pg. 30

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pg. 33

- 1 2 Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pg. 38

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pp. 35–36

- 1 2 Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pg. 45

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pp. 42–43

- ↑ "The First Latina to Conquer Hollywood". Filmint.nu. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pp. 44-45

- ↑ Hall (2013), pp. 265

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Hall (2013), p. 266

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, p. 56

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pp. 49–50

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nidia Martínez de León (10 April 2018). "35 años sin la estrella mexicana Dolores del Río". Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pp. 16

- ↑ Hall (2013), pg. 267

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pp. 14–15

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pp. 25–27–28

- ↑ "Dolores del Río, la belleza y el talento mexicano que se ganó a Hollywood". Europa Press (in Spanish). 3 August 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pp. 32–35

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pg. 58.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pg. 20

- ↑ Ramón (1997),vol. 3, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pp. 49–50; vol. 3, pp. 37–39

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, p. 46

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pg. 48

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pp. 50–51

- ↑ "GREAT MOMENTS - San Francisco Film Festival". history.sffs.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- 1 2 "SU PIEL, LA CERCANIA DEL INCIENSO; SUS OJOS, LA HERIDA LIQUIDA DE LA OBSIDIANA: CARLOS FUENTES - Proceso" (in Spanish). Proceso. 16 April 1983. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 2, pp. 49–50; vol. 3, pg. 54

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pg. 60

- ↑ McNulty, Thomas (2011). Errol Flynn: The Life and Career. McFarland. p. 32. ISBN 9780786468980.

- ↑ "Secret Marriage Denial". The Barrier Miner. Broken Hill, NSW: National Library of Australia. 25 October 1932. p. 1. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Raquel, Peguero (3 August 2004). "Dolores del Río: su vida, un cuento de hadas" (in Spanish). El Universal. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pg. 11

- ↑ Franco Dunne (2003), pg. 79

- ↑ Moreno, Luis (2002). Rostros e Imagenes. Editorial Celuloide. pp. 138, 141. ISBN 9789709338904.

- ↑ Ramón (1997),vol. 2, pp. 51–52

- ↑ Félix, María (1994). Todas mis Guerras. Clío. p. 84. ISBN 9686932089.

- ↑ María Félix speaks about Dolores del Río in an interview Archived 8 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Youtube.com; accessed 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Price (2014), pg. 372

- 1 2 Ramón (1997),vol. 2, pp. 58–59

- ↑ Javier García Java (11 April 2018). "Hoy se cumplen 35 años del fallecimiento de la actriz Dolores del Río". El Sol de México (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ↑ Cesar, Romero (21 March 2018). "Panteón Civil de Dolores y Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres". Go app! mx (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Franco Dunn, Cinta (2003), pp. 21-22

- ↑ Carr. (1979) p. 32

- ↑ Hershfield (2000), pg. 9

- ↑ Gray, Emma (22 April 2013). "Dolores del Rio, Mexican Movie Star, Was Photoplay's 'Best Figure In Hollywood' In 1931 (PHOTOS)". huffingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ↑ Carr (1978), pg. 229

- ↑ Lazaro Sarmiento (2013-04-16). "''Buena suerte viviendo: Dolores del Río" (in Spanish). Lazarosarmiento.blogspot.mx. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ Poniatowska, Elena (1995). "Dolores del Río: The Face of the Mexican Cinema". SOMOS: 24.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pp. 19-20

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 1, pg. 53

- ↑ Riva, Maria (1994). Marlene Dietrich. Ballantine Books. pp. 489, 675. ISBN 0-345-38645-0.

- ↑ Hall (2013), pg. 4

- ↑ "Dolores del Rio: Muses, Cinematic Women". theredlist.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016.

- ↑ SOMOS:Dolores del Río: El Rostro del Cine Mexicano. Editorial Televisa. 1995. p. 26.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "Dos o tres episodios mexicanos de Orson Welles" (in Spanish). Nexos. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- ↑ "SU PIEL, LA CERCANIA DEL INCIENSO; SUS OJOS, LA HERIDA LIQUIDA DE LA OBSIDIANA: CARLOS FUENTES - Proceso" (in Spanish). proceso.com.mx. 16 April 1983. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ↑ "Artes e Historia México". Arts-history.mx (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 August 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Orry-Kelly, Women He's undressed" Archived 15 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Theodoracopulos, Taki (9 March 2007). "All Quiet on the K Street Front – Taki's Magazine". Takimag.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ↑ Idalia, María. "Dolores del Río se retira del cine" Cinema Reporter no. 290, pg. 11 (1948).

- ↑ Tomás, Delclós (13 April 1983). "Muere Dolores del Río, la actriz mexicana que enamoró a Hollywood". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pp. 26-27

- ↑ Dolores del Río: El Rostro del Cine Mexicano, Revista SOMOS México, 1994, ed. Televisa, pp. 70–72

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pg. 36

- ↑ Jornada, La. "Covarrubias veía el mundo como una acumulación de culturas: Juan Coronel - La Jornada". www.jornada.unam.mx (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ↑ "Dolores del Río, el esplendor de un rostro" (in Spanish). loscabosnews.com.mx. May 2, 2016. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ↑ Ramón (1997), vol. 3, pg. 38

- ↑ Williams, Cecil B. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1964, pp. 155–56.

- ↑ Dolores del Río: La Mexicana Divina, Revista SOMOS México, 2002, ed. Televisa, pg. 71

- ↑ "From Hollywood and back: Dolores del Río, a transnational star". Archived from the original on 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Carr. (1979) pg. 42

- ↑ Reyes, Luis (1994), pg. 19

- ↑ "Lupita Nyong'o Ended Kenya and Mexico's Mini-Feud Over Her Nationality". Archived from the original on 25 March 2017.

- ↑ "Alfredo de Batuc". Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Deoima, Kate. Hollywood High School Archived 15 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine., About.com; retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ↑ Johnson, Reed. A marriage as a work of art; Eloy Torrez paints with intensity. Margarita Guzman assists with a sense of calm. But it was her brush with death that helped him see his work in a new light. Archived 4 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine." Los Angeles Times, 12 October 2003, pg. E48. Sunday Calendar, Part E, Calendar Desk; retrieved 23 March 2010. "HOLLYWOOD HIGH: Eloy Torrez and his mural on an east-facing wall of the..."

- ↑ Fandino, Cesar (14 October 2011). "Estatua de Dolores del Río" (in Spanish). Flickr. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "El Universal DF – Develan busto de Dolores del Río en Parque Hundido". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Blvd dolores del rio Durango". Yotellevo.mx. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- ↑ "Zelig (1983)". IMDb. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ "RKO 281 (1999 TV Movie)". IMDb. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ México, El Universal, Compañia Periodística Nacional. "Dolores del Río, a la Rotonda". Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ↑ "Google honors actress Dolores del Rio with new Doodle". Archived from the original on 3 August 2017.

References

- Beltrán, Mary (2009). Latina/o stars in U.S. eyes: the making and meanings of film and TV stardom. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252076510.

- Carr, Larry (1979). More Fabulous Faces: The Evolution and Metamorphosis of Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn, Dolores del Río, Carole Lombard and Myrna Loy. Doubleday and Company. ISBN 0-385-12819-3.

- Chandler, Charlotte (2006). The Girl Who Walked Home Alone: Bette Davis, A Personal Biography. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743289054.

- Félix, María (1993). Todas mis Guerras. Clío. ISBN 9686932089.

- Franco Dunn, Cinta (2003). Grandes Mexicanos Ilustres: Dolores del Río (Great Illustrious Mexicans: Dolores del Río). Promo Libro. ISBN 84-492-0329-5.

- Hall, Linda (2013). Dolores del Río: Beauty in Light and Shade. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804786218.

- Hershfield, Joanne (2000). The invention of Dolores del Río. University of Minnesota. ISBN 0-8166-3410-6.

- McNulty, Thomas (2004). Errol Flynn: The Life and Career. McFarland. ISBN 9780786417506.

- Moreno, Luis (2002). Rostros e Imagenes (Faces and Images). Editorial Celuloide. ISBN 9789709338904.

- Noble, Andrea (2005). Mexican National Cinema. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415230100.

- Price, Victoria (2014). Vincent Price: A Daughter's Biography. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781497649408.

- Ramón, David (1997). Dolores del Río vol. 1: Un cuento de hadas (Dolores del Río vol. 1: A Fairy Tale). Editorial Clío. ISBN 968-6932-36-4.

- Ramón, David (1997). Dolores del Río vol. 2: Volver al origen (Dolores del Río vol. 2: Return to the Origin). Editorial Clío. ISBN 968-6932-37-2.

- Ramón, David (1997). Dolores del Río vol. 3: Consagración de una Diva (Dolores del Río vol. 3: Consecration of a Diva). Editorial Clío. ISBN 968-6932-38-0.

- Revista Somos: Dolores del Río: El Rostro del Cine Mexicano (Dolores del Río: The Face of the Mexican Cinema). Editorial Televisa S.A de C.V. 1995.

- Revista Somos: Dolores del Río: La Mexicana Divina (Dolores del Río: The Divine Mexican). Editorial Televisa S.A de C.V. 2002.

- Revista Somos: Katy Jurado: Estrella de Hollywood orgullosamente mexicana (Katy Jurado: Proudly Mexican Hollywood Star). Editorial Televisa S.A de C.V. 1999.

- Reyes, Luis, Rubie, Peter (1994). Hispanics in Hollywood: An Encyclopedia of Film and Television. Garland. ISBN 0815308272.

- Riva, Maria (1994). Marlene Dietrich. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-38645-0.

- Torres, José Alejandro (2004). Los Grandes Mexicanos: Dolores del Río (The Greatest Mexicans: Dolores del Río). Grupo Editorial Tomo, S.A. de C.V.

- Tuñón, Julia (2003). The Cinema of Latin America. Wallflower Press. ISBN 9780231501941.

- Zolov, Eric (2015). Iconic Mexico: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610690447.

Further reading

- Agrasánchez Jr., Rogelio (2001). Bellezas del cine mexicano/Beauties of Mexican Cinema. Archivo Fílmico Agrasánchez. ISBN 968-5077-11-8.

- Bodeen, DeWitt (1976). From Hollywood: The Careers of 15 Great American Stars. Oak Tree. ISBN 0498013464.

- E. Fey, Ingrid., Racine, Karen (2000). Strange Pilgrimages: Exile, Travel, and National Identity in Latin America, 1800-1990s: "So Far from God, So Close to Hollywood: Dolores del Río and Lupe Vélez in Hollywood, 1925–1944,". Wilmington, Delaware, Scholarly Resources. ISBN 0-8420-2694-0.

- Lacob, Adrian (2014). Film Actresses Vol.23 Dolores del Rio, Part 1. On Demand Publishing, LLC-Create Space. ISBN 9781502987686.

- Lopez, Ana M. (1998). "From Hollywood and Back: Dolores del Rio, a Trans (national) Star." Studies in Latin American Popular Culture 17. ISSN 0730-9139.

- Mendible, Myra (2010). From Bananas to Buttocks: The Latina Body in Popular Film and Culture. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-77849-X.

- Nericcio, William (2007). Tex[t]-Mex: Seductive Hallucinations of the "Mexican" in America. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71457-2.

- Parish, James Robert (2002). Hollywood divas: the good, the bad, and the fabulous. Contemporary Books. ISBN 9780071408196.

- Parish, James Robert (2008). The Hollywood beauties. Arlington House. ISBN 9780870004124.

- Ramón, David (1993). Dolores del Río: Historia de un rostro (Dolores del Río: Story of a Face). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CCH Dirección Plantel Sur. ISBN 9789686717099.

- Rivera Viruet, Rafael J.; Resto, Max (2008). Hollywood: Se Habla Español. Terramax Entertainment. ISBN 0-981-66500-4.

- Rodriguez, Clara E. (2004). Heroes, Lovers, and Others: The Story of Latinos in Hollywood. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-33513-9.

- Ruíz, Vicki; Sánchez Korrol, Virginia (2006). Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. 1. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34681-9.

- Shipman, David (1995). The Great Movie Stars: The Golden Years. Little Brown and Co. ISBN 0-316-78487-7.

- Taibo, Paco Ignacio (1999). Dolores del Río: mujer en el volcán (Dolores del Río: Woman in the Volcano). GeoPlaneta, Editorial, S. A. ISBN 9789684068643.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dolores del Río. |

- Dolores del Río on IMDb

- Dolores del Río at AllMovie

- Dolores del Río at the TCM Movie Database

- Dolores del Río at the Cinema of Mexico site of the ITESM (in Spanish)

- Dolores del Río profile, Virtual-History.com

- Dolores del Río at Find a Grave

- The Dolores del Rio mural 1990 by artist Alfredo de Batuc, 6529 Hollywood Boulevard + Hudson St, Los Angeles, California

- Dolores del Rio statue on Hollywood-La Brea Boulevard

- Photographs of Dolores del Rio