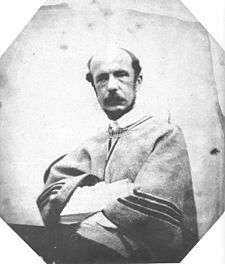

Johann Moritz Rugendas

Johann Moritz Rugendas (29 March 1802 – 29 May 1858) was a German painter, famous for his works depicting landscapes and ethnographic subjects in several countries in the Americas, in the first half of the 19th century. Rugendas is considered "by far the most varied and important of the European artists to visit Latin America"[1] whom Alexander von Humboldt influenced.[2] Rugendas is also the subject of César Aira's 2000 novel, An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter.

Biography

Rugendas was born in Augsburg, then part of the Prince-Bishopric of Augsburg in the Holy Roman Empire, now Germany, into the seventh generation of a family of noted painters and engravers of Augsburg (he was a great grandson of Georg Philipp Rugendas, 1666–1742, a celebrated painter of battles),[3] and studied drawing and engraving with his father, Johann Lorenz Rugendas II (1775–1826). From 1815-17, he studied with Albrecht Adam (1786–1862), and later in the Academy de Arts of Munich, with Lorenzo Quaglio II (1793–1869). When Rugendas was born, Augsburg was a Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire, and after the Napoleonic Wars, it became in 1806 a city in the newly created Kingdom of Bavaria.

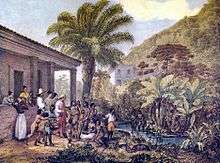

Inspired by the artistic work of Thomas Ender (1793–1875) and the travel accounts in the tropics by German naturalists Johann Baptist von Spix (1781–1826) and Carl von Martius (1794–1868), in the course of the Austrian Brazil Expedition, Rugendas arrived in Brazil in 1822, hired as an illustrator for Baron von Langsdorff's scientific expedition to Brazil. Langsdorff was the consul-general of the Russian Empire in Brazil and had a farm in the northern region of Rio de Janeiro, where Rugendas went to live with other members of the expedition.

In this capacity, Rugendas visited the Serra da Mantiqueira and the historical towns of Barbacena, São João del Rei, Mariana, Ouro Preto, Caeté, Sabará and Santa Luzia. Just before the fluvial phase of the expedition started (a fateful journey to the Amazon), he became alienated from von Langsdorff, left the expedition and was replaced by the artists Adrien Taunay and Hércules Florence. However, Rugendas remained on his own in Brazil until 1825, exploring and recording his many impressions of daily life in the provinces of Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, and quickly the coastal provinces of Bahia and Pernambuco on his journey back to Europe. He produced mostly drawings and watercolors.[4]

On his return to Europe between 1825 and 1828, Rugendas lived successively in Paris, Augsburg and Munich, with the aim of learning new art techniques, such as oil painting. There, he published from 1827 to 1835, with the help of Victor Aimé Huber, his monumental book Voyage Pittoresque dans le Brésil (Picturesque Voyage to Brazil), with more than 500 illustrations, which became one of the most important documents about Brazil in the 19th century.[5]

He studied in Italy, but re-inspired by explorer and naturalist, Alexander Humboldt (1769–1859), Rugendas sought financial support for a much more ambitious project of recording pictorially the life and nature of Latin America; in his words "an endeavor to truly become the illustrator of life in the New World". In 1831 he traveled first to Haiti, and then to Mexico. In Mexico, he did drawings and watercolors of Morelia, Teotihuacan, Xochimilco, and Cuernavaca.[6] He also began to use oil painting, with excellent results. Unfortunately, Rugendas was incarcerated and expelled from the country after he became involved in a failed coup against Mexico's president, Anastasio Bustamante, in 1834.

From 1834-44 he travelled to Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru and Bolivia, and finally went back to Rio de Janeiro, in 1845. Well-accepted and feted by the court of Emperor Dom Pedro II, he executed portraits of several members of the royal court and participated in an artistic exposition. At the age of 44, in 1846, Rugendas departed for Europe.[7]

Depicting black people in Brazil

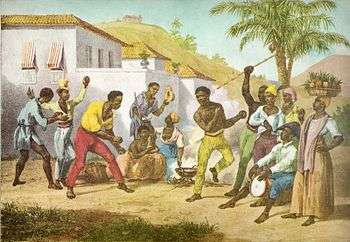

From 1822-1825, as part of the Langsdorff expedition, Johann Moritz Rugendas depicted black people living in Brazil. Along with other ethnographic artists who worked in Brazil, like Jean-Batiste Debret, and François-August Biard, Rugendas is part of the tropical romanticism. This movement challenged the dichotomy between nature and civilization and considered places like colonial Brazil a harmonious environment to racial mixing.[8]

Tropical romanticism was one of the elements that influenced the representations of black people made by Rugendas. According to Freitas, one type of illustration Rugendas used was the bust of black people of varied origins. This type of illustration details the physical characteristics of black men and women focusing on hairstyles, adornments, marks and scars, and types of nose, lips, and eyes, demonstrating the ethnographic purpose of these drawings. In the same lithograph, the artist depicts four or five busts of men and women to compare differences and similarities among nations of origin, but also to identify different degrees of civilization. He identified more savage people depicting them with skin marks and deformities and normally without clothes.[9] On the other hand, criollos were represented wearing clothes and jewelry which meant a step forward toward civilization if compared with black Africans. Rugendas celebrated black people born in Brazil, who were more polished and benevolent than Africans.[10]

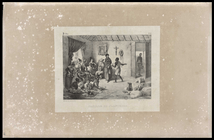

The second type of representation in which Rugendas depicted black people was the painting of scenes. These images presented activities of urban work such as street commerce, water transportation, and laundry. The main focus was in the activity and the landscape rather than in detailing variation between blacks of different origins. For this reason, a generic type of black was represented in these scenes. In other words, the differential traces that were highlighted in the busts were neutralized in the pictures of scenes. The work performed by black people was represented by Rugendas as a civilizing element that allowed black people to develop themselves and to have social mobility.[11]

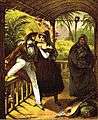

Rugendas, by influence of Alexander von Humboldt, considered environmental conditions as determinant factors to human development and thus believed that the lack of education and civilizing elements in Africa contributed to the inferiority of the African race. Also by influence of Humboldt, who was an abolitionist, Rugendas disapproved Brazilian slavery system and defended a gradual and progressive emancipation.[10] The historian Robert Slenes defended that Rugendas had a political agenda that worked together with his ethnographic work. To Slenes, the artist had a compromise with a conservative Christian reformism, characteristic of French abolitionist movement. Although Rugendas defended the gradual emancipation, the artist understood Brazilian slavery as a new life for Africans, who got the chance to the Christian experience.[12] In some images, for example the "Enterro de um Negro na Bahia," Rugendas identified the dead body of a "black man with another corpse: the suffering Christ the ‘Savior’ honored by the city’s name."[12] There are other images where elements of Catholicism are present such as "Mercado de Negros" and "Familia de Agricultores", the latter one of the few images Rugendas represents black people in private environments.

Petrônio Domingues defends that the artistic work of foreigner painters and ethnographers in the nineteenth-century Brazil had a deep impact in the built of racial imaginary. The romantic point of view on how slavery worked in Brazil contributed to creation of the myth of racial democracy.[13] Outside Brazil, the images Rugendas produced had relative success, for he published a book with his travel log and a collection of one hundred pictures, called “Viagem Pitoresca através do Brazil,” in Portuguese, “Voyage Pittoresque dans le Brésil”, in French, and “Malerische Reise in Brasilien”, in German. Moreover, the nineteenth century experienced the spreading of travel books and the development of lithographs.[14] Rugendas’ images helped to spread the idea of racial harmony inside and outside Brazil.

Death

He died on 29 May 1858 in Weilheim an der Teck, Germany, King Maximilian II of Bavaria having acquired most of his works in exchange for a life pension. His painting "Columbus taking Possession of the New World" (1855) is on view at the Neue Pinakothek, in Munich.

See also

Gallery

Costumes in Rio, 1823

Costumes in Rio, 1823 Slave hunter, 1823

Slave hunter, 1823 Indians in a farm, 1824

Indians in a farm, 1824 Capoeira or the Dance of War, 1835

Capoeira or the Dance of War, 1835 Fête de Sainte Rosalie, Patrone des nègres, 1835

Fête de Sainte Rosalie, Patrone des nègres, 1835 Customs on central Valparaíso.

Customs on central Valparaíso. Johann Moritz Rugendas.

Johann Moritz Rugendas.

References

- ↑ Mary Jo Miles, "Johann Moritz Rugendas" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, p. 619. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ↑ Sigrid Achenbach. Kunst um Humboldt: Reisestudiern aus Mittel- un Südamerika von Rugendas, Bellerman un Hildebrandt im Berliner Kupferstichkabinett. Berlin: Kupferstichkabinett Statliche Musee 2009.

- ↑ Lody, Raul Giovanni da Motta (2004). Cabelos de axé: identidade e resistência. Senac. p. 54. ISBN 85-7458-162-3.

- ↑ Diener, Costa, "Rugendas e o Brasil"

- ↑ Miles, "Rugendas" p. 619.

- ↑ Miles, "Johann Moritz Rugendas", p. 619.

- ↑ Miles, "Rugendas", p. 619.

- ↑ Araujo, Ana Lucia. Brazil through French Eyes: A Nineteenth-Century Artist in the Tropics. University of New Mexico Press, 2015. p.35-6.

- ↑ Freitas, Iohana Brito de. Cores e Olhares no Brasil Oitocentista: os Tipos de Negros de Rugendas e Debret. Masters thesis. Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2009. p.65.

- 1 2 Diener, Pablo, Maria De Fátima G Costa, and Johann Moritz Rugendas. Rugendas e o Brasil. São Paulo, SP: Capivara, 2002. p.144.

- ↑ Freitas, Iohana Brito de. Cores e Olhares no Brasil Oitocentista: os Tipos de Negros de Rugendas e Debret. Masters thesis. Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2009. p.68.

- 1 2 Slenes, Robert W. "African Abrahams, Lucretias and Men of Sorrows: Allegory and Allusion in the Brazilian Anti-slavery Lithographs (1827-1835) of Johann Moritz Rugendas," Slavery & Abolition 23, no.2, (2002): 147.

- ↑ Domingues, Petrônio. "O Mito da Democracia Racial e a Mestiçagem no Brazil (1889-1930)." Diálogos Latinoamericanos, no. 10 (2005), 119.

- ↑ Thomas, Sarah. “On the spot: Traveling artists and abolitionism,1770–1830," Atlantic Studies 8, no.2, (2011): 218.

Further reading

- Ades, Dawn, Art in Latin America. 1989.

- Diener, P.: Rugendas, 1802-1858. Wissner; Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Augsburg and Santiago de Chile, 1997. A massive catalogue of works in Spanish and Portuguese.

- Diener, P.; COSTA, M. de F. (org.). Rugendas e o Brasil. Obra completa. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Capivara, 2012.

- Lemos, Carlos. The Art of Brazil 1983.

- Miles, Mary Jo. "Johann Moritz Rugendas" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, p. 619. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Milla Batres, Carlos. Juan Mauricio Rugendas: El Perú Romántico del siglo XIX. Lima: Milla Batres 1975.

- Juan Mauricio Rugendas en Mexico (1831-1834) : un pintor en la senda de Alejandro de Humboldt ; exposición del Instituto Ibero-Americano, Patrimonio Cultural Prusiano, Berlin. Berlin : Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut, 2002.

External links