Remedios Varo

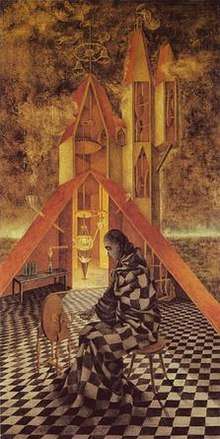

| Remedios Varo | |

|---|---|

Useless Science or the Alchemist, 1955 | |

| Born |

Remedios Varo Uranga 16 December 1908 Anglés, Spain |

| Died |

8 October 1963 (aged 54) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Surrealism |

Remedios Varo Uranga (16 December 1908 – 8 October 1963) was a Spanish surrealist artist.

Born in Anglès (north of Catalonia), Spain in 1908, she studied at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid. Varo spent her formative years between France and Barcelona and was greatly influenced by the surrealist movement. While still married to her first husband Gerardo Lizarraga, Varo met her second partner, the French surrealist poet Benjamin Péret, in Barcelona. During the Spanish Civil War she fled to Paris with Péret leaving Lizarraga behind (1937). She was forced into exile from Paris during the German occupation of France and moved to Mexico City at the end of 1941 when the Mexican president, Lázaro Cardenas, made it a policy to welcome Spanish and European refugees. She died in 1963, at the height of her career, from a heart attack, in Mexico City.

Personal life

She was born María de los Remedios Alicia Rodriga Varo y Uranga in Anglès, a small town in the province of Girona, north of Spain in 1908.[1] Her birth helped her mother get over the death of another daughter, which is the reason behind the name.[2]

Varo’s father, Rodrigo Varo y Zajalvo, was a hydraulic engineer, and the family traveled the Iberian Peninsula and into North Africa for work.[3] To keep Remedios busy during these long trips, her father had her copy the technical drawings of his work with their straight lines, radii, and perspectives, which she reproduced faithfully. He encouraged independent thought and supplemented her education with science and adventure books, notably the novels of Alexandre Dumas, Jules Verne, and Edgar Allan Poe. As she grew older, he provided her with text on mysticism and philosophy. Those first few years of her life left an impression on her that would later show up in motifs like machinery, furnishing, artifacts, and Romanesque and Gothic architecture unique to Anglès. Varo’s mother, Ignacia Uranga Bergareche, was born to Basque parents in Argentina. She was a devout Catholic and commended herself to the patron saint of Anglès, the Virgin of Los Remedios, promising to name her first daughter after the saint.[1][2]

Varo was given the basic education deemed proper for young ladies of a good upbringing at a convent school - an experience that fostered her rebellious tendencies. Varo took a critical view of religion and rejected the religious ideology of her childhood education and instead clung to the liberal and universalist ideas that her father instilled in her.[1]

Varo had two brothers Rodrigo and Luis. The latter died in 1936 fighting with the Nationalist side.

The family moved to Madrid and Varo entered the Escuela de Bellas Artes (1924). In 1930 she married a young painter named Gerardo Lizarraga in San Sebastián. She married Lizarraga in order to gain autonomy from her family and to continue her career as a painter given that in traditional 1930's Spain, women were only able gain that autonomy from their parents through marriage.[4] The couple left Spain for Paris to be nearer to where much of Europe’s art scene was.[1][2]

After a year, Lizarraga got a job in Spain and the couple moved to Barcelona, at the time the European centre of the artistic avant-garde. Towards 1937 Varo met political activist and artist Esteban Francés and leaving her husband behind, moved to France with both Péret and Francés, escaping from the political unrest caused by the onset of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Varo never divorced Lizarraga and had different partners/lovers throughout her life, but she also remained friends with all of them, in particular with husband Lizarraga and Péret. Varo shared a studio in Paris with Peret and Frances.

Despite the social circles, they lived in poverty, with Varo having to copy and even forge paintings in order to get by.[2] At the beginning of World War II, Péret was imprisoned for his political beliefs and she along with him as his partner. A few days after Varo was freed, the Germans entered Paris, and she was forced to join other French refugees. Peret was freed soon after, and the two managed to obtain documents to allow them to escape the war to Mexico.[2] On 20 November 1941 Varo, along with Peret and Rubinstein, boarded the Serpa Pinto in Marseilles to flee war-torn Europe. As a result of this terror she faced, many stated that as an adult Varo was scarred by these events.

She initially considered Mexico a temporary haven, but except for a year spent in Venezuela, she would reside in Mexico for the rest of her life.[5]

Formative years

The very first works of Varo's, a self-portrait and several portraits of family members, date to 1923 when she was studying for a baccalaureate at the School of Arts and Crafts.

In 1924, aged 15, she enrolled at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, in Madrid, the alma mater of Salvador Dalí and other renowned artists.[6] Varo got her diploma as a drawing teacher in 1930.[1] She also exhibit in a collective exhibition organised by the Unión de Dibujantes de Madrid. At school, surrealistic elements were already apparent in her work, as it had arrived in Spain from France, and she took an early interest in it.[2] While in Madrid, Varo had her initial introduction to Surrealism through lectures, exhibitions, films, and theater. She was a regular visitor to the Prado Museum and took particular interest in the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, most notably The Garden of Earthly Delights, as well as other artists, such as Francisco de Goya.

Early career

As a young woman Varo had no doubts that she was meant to be an artist. After spending a year in Paris, Varo moved to Barcelona and formed her first artistic circle of friends, which included Josep-Lluis Florit, Óscar Domínguez, and Esteban Francés.[2] Varo soon separated from her husband and shared a studio with Francés in a neighborhood filled with young avant-garde artists. The summer of 1935 marked Varo’s formal invitation into Surrealism when French surrealist Marcel Jean arrived in Barcelona. That same year, along with Jean and his artist friends, Dominguez and Francés, Varo took part in various surrealist games such as cadavres exquis that was meant to explore the subconscious association of participants by pairing different images at random. These cadavres exquis, meaning exquisite corpses, perfectly illustrated the principle André Breton wrote in his Surrealist manifestos. Varo soon joined a collective of artists and writers, called the Grupo Logicofobista, who had an interest in Surrealism and wanted to unite art together with metaphysics, while resisting logic and reason. Varo exhibited with this group in 1936 at the Galería Catalonia although she recognized they were not pure Surrealists.[1]

During her time in Barcelona she worked as a publicist with company J. Walter Thompson.

Career

Europe

It was through Peret that Remedios Varo met André Breton and the Surrealist circle, which included Leonora Carrington, Dora Maar, Roberto Matta, Wolfgang Paalen, and Max Ernst among others. Shortly after arriving in France, Varo took part in the International Surrealist exhibitions in Paris and in Amsterdam in 1938. She drew vignettes for the Dictionnaire abregé du surrealisme and the magazines Trajectoire du Rêve, Visage du Monde and Minotaure featured her work. In late 1938, she participated in a collaborative series, Jeu de dessin communiqué (The Game of Communicated Drawing), of works with Breton and Peret. The series was much like a game. It began with an initial drawing, which was shown to someone for 3 seconds, and then that person tried to recreate what they had been shown. The cycle continued with their drawing and so on. Apparently, this led to very interesting psychological implications that Varo later used in her paintings many times.

Compared to her time in Mexico, she produced very little work while working in Paris. This may have been due to her status as a femme enfant and the way women were never taken seriously as surrealist artists. She said, reflecting on her time in Paris, “Yes, I attended those meetings where they talked a lot and one learned various things; sometimes I participated with works in their exhibitions; I was not old enough nor did I have the aplomb to face up to them, to a Paul Eluard, a Benjamin Peret, or an Andre Breton. I was with an open mouth within this group of brilliant and gifted people. I was together with them because I felt a certain affinity. Today I do not belong to any group; I paint what occurs to me and that is all.”[7]

Mexico

.jpg)

.jpg)

In Mexico, she met regularly with other European artists such as Gunther Gerzso, Kati Horna, José Horna, and Wolfgang Paalen. In Mexico, she met native artists such as Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, but her strongest ties were to other exiles and expatriates, notably the English painter Leonora Carrington and the French pilot and adventurer, Jean Nicolle. However, because Mexican muralism still dominated the country’s art scene, surrealism was not generally well received. She worked as an assistant to Marc Chagall with the design of the costumes for the production of the ballet Aleko, which premiered in Mexico City in 1942.[1]

She worked at other jobs including in publicity for pharmaceutical company Bayer and decorating for Clar Decor. In 1947, Péret returned to Paris, and Varo traveled to Venezuela, living there for two years.[1] She returned to Mexico and began her third and last important relationship with Austrian refugee Walter Gruen, who had endured concentration camps before escaping Europe. Gruen believed fiercely in Varo, and he gave her the economic and emotional support that allowed her to fully concentrate on her painting.[2] In 1955, Varo had her first individual exhibition at the Galería Diana in Mexico City, which was well received. One reason for this was that Mexico had opened up to other artistic trends. Buyers were put on waiting lists for her work. Even Diego Rivera was supportive. Her second showing was as the Salón de la Arte de Mujer in 1958. In 1960, her representative, Juan Martín, opened his own gallery and showed her work there, and opened a second in 1962, at the height of her career. Only a year after that opening, she died.[1][2] Her work is well known in Mexico, but not as commonly known throughout the rest of the world.[8]

She has said about working in Mexico, “for me it was impossible to paint among such anxiety. In this country I have found the tranquility that I have always searched for.”[7]

Major influences

Artistic influences

Renaissance art inspired harmony, tonal nuances, unity, and narrative structure in Varo’s paintings. The allegorical nature of much of Varo's work especially recalls the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, and some critics, such as Dean Swinford, have described her art as "postmodern allegory," much in the tradition of Irrealism.

Varo was influenced by styles as diverse as those of Francisco Goya, El Greco, Picasso, and Braque. While André Breton was a formative influence in her understanding of Surrealism, some of her paintings bear an uncanny resemblance to the Surrealist creations of the modern Greek-born Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico.

While there is little overt influence of Mexican art on her work, Varo and the other surrealists were captivated by the seemingly porous borders between the marvelous and the real in Mexico.[7]

Varo's painting The Lovers served as inspiration for some of the images used by Madonna in the music video for her 1995 single "Bedtime Story".

Philosophical influences

_Remedios_Varo_-_Ascensin_Al_Monte_Anlogo_(5579572452).jpg)

She considered surrealism as an "expressive resting place within the limits of Cubism, and as a way of communicating the incommunicable".[2]

Even though Varo was critical of her childhood religion, Catholicism, her work was influenced by religion. She differed from other Surrealists because of her constant use of religion in her work.[3] She also turned to a wide range of mystic and hermetic traditions, both Western and non-Western for influence. She was influenced by her belief in magic and animistic faiths. She was very connected to nature and believed that there was strong relation between the plant, human, animal, and mechanical world. Her belief in mystical forces greatly influenced her paintings.[6] Varo was aware of the importance of biology, chemistry, physics and botany, and thought it should blend together with other aspects of life.[6] Her fascination for science, including Einstein's theory or relativity and Darwinian evolution, has been noted by admirers of her art.[9]

She turned with equal interest to the ideas of Carl Jung as to the theories of George Gurdjieff, P. D. Ouspensky, Helena Blavatsky, Meister Eckhart and the Sufis, and was as fascinated with the legend of the Holy Grail as with sacred geometry, witchcraft,[10] alchemy and the I Ching. In 1938 and 1939 Varo joined her closest companions Frances, Roberto Matta and Gordon Onslow Ford in exploring the fourth dimension, basing much of their studies off of Ouspensky's book Tertium Oganum. The books Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy by Grillot de Givry and The History of Magic and the Occult by Kurt Seligmann were highly valued in Breton's Surrealist circle. She saw in each of these an avenue to self-knowledge and the transformation of consciousness.

She was also greatly influenced by her childhood journeys. She often depicted out of the ordinary vehicles in mystifying lands. These works echo her family travels in her childhood.[3]

Also, the Surrealist movement tended to degrade women. Some of Varo's art elevated women, while still falling under Surrealism. But it was not necessarily her intention for her work to address problems in gender inequality. But, her art and actions challenged the traditional patriarchy, and it was mainly Wolfgang Paalen who encouraged her in this with his theories about the origins of civilization in matriarchal cultures and the analogies between pre-classic Europe and pre-Mayan Mexico.[3][11]

Relationship with Leonora Carrington and Kati Horna

All refugees that were forced to flee from Europe to Mexico City after World War two, Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Kati Horna formed a bond that would immensely affect their lives and work. They all lived in proximity to each other in Colonia Roma.

Varo and Carrington had previously met while living in Paris through Andre Breton. Although Horna did not meet the other two until they were all in Mexico City, she was already familiar with the work of Varo and Carrington after being given a few of their paintings by Edward James, a British poet and patron of the surrealist movement.

All three would attend the meetings of followers of the Russian mystics Peter Ouspensky and George Gurdjieff.[12] They were inspired by Gurdjieff’s study of the evolution of consciousness and Ouspensky’s idea of the possibility of four dimensional painting. Though deeply influenced by the idea of the Russian mystics, the women often ridiculed the practices and behavior of those in the circle.

After becoming friends, Varo and Carrington began writing collaboratively and wrote two unpublished plays together: El santo cuerpo grasoso and Lady Milagra - the latter unfinished. Using a technique similar to that of the game called Cadavre Exquis, they took turns writing small segments of text and put them together. Even when not writing together, they were often working collaboratively, often drawing from the same sources of inspiration and using the same themes in their paintings. Despite the fact that their work is extremely similar, there is one major difference: Varo’s painting is about line and form, while Carrington's work is about tone and color. Varo and Carrington would stay extremely close friends for 20 years, until Varo’s death in 1963.[13]

Interpretations of Varo's artwork

Varo often painted images of women in confined spaces, achieving a sense of isolation. Later in her career, her characters developed into her emblematic androgynous figures with heart-shaped faces, large almond eyes, and the aquiline noses that represent her own features. Varo often depicted herself through these key features in her paintings, regardless of the figure's gender.[6]

Varo’s legacy

In 1963 Varo died of a heart attack. Breton commented that the death made her "the sorceress who left too soon."[1] Her mature paintings, fraught with arguably feminist meaning, are predominantly from the last few years of her life. Varo’s partner for the last 15 years of her life, Walter Gruen, dedicated his life to cataloguing her work and ensuring her legacy. The paintings of androgynous characters that share Varo’s facial features, mythical creatures, the misty swirls and eerie distortions of perspective are characteristic of Varo’s unique strain of surrealism. Varo has painted images of isolated, androgynous, auto-biographical figures to highlight the captivity of the true woman. While her paintings have been interpreted as more surrealist canvases that are the product of her passion for mysticism and alchemy, or as auto-biographical narratives, her work carries implications far more significant.[8]

In 1971 the posthumous retrospective exhibition organised by the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City, drew the largest audiences in its history - larger than those for Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco.[8]

More than fifty of her works were displayed in a retrospective exhibition in 2000 at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC.[14]

Currently the ownership of 39 of her paintings, first loaned and then given by Gruen to Mexico City's Museum of Modern Art in 1999, is in dispute. Varo's niece Beatriz Varo Jiménez of Valencia, Spain, claims Gruen had no rights to those works. Gruen, now 91, claims he inherited no works from Varo, who died intestate. Varo never divorced the husband she married in Spain in 1930: a court denied Gruen's request in 1992 to be given inheritance rights as the artist's common-law husband. He and his wife, Alexandra, whom he married in 1965, acquired all the paintings given to the museum on the open market after Varo's death and are therefore his to give. He said he gave the only painting in Varo's studio at the time of her death, Still Life Reviving, to the artist's mother. The work was auctioned at Sotheby's New York in 1994 for $574,000.

The book The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon features a scene in which the main character recalls crying in front of a painting by Varo titled, Bordando el Manto Terrestre.[15]

Selected list of works

- 1935 El tejido de los sueños (Fabric of Dreams)

- 1942 Gruta mágica (Magical Grotto)

- 1947 Paludismo (wrongly known as Libélula) (Malaria (anopheles mosquito, Anopheles gambiae))

- 1947 El hombre de la guadaña (muerte en el mercado) (The Man with the scythe (death in the market))

- 1947 La batalla (The Battle)

- 1947 Wahgwah

- 1947 Amibiasis o los vegetales (Amebiasis or Plant)

- 1955 Useless Science or the Alchemist

- 1955 Ermitaño meditando (Meditating Hermit)

- 1955 La revelación o el relojero[16]

- 1955 Trasmundo (Transworld)

- 1955 The Lovers

- 1955 El flautista (The Piper)

- 1955 Solar Music'[8]

- 1956 El paraíso de los gatos (Paradise of cats)

- 1956 To the Happiness of Women

- 1956 Les feuilles mortes (Dead Leaves)

- 1956 Harmony'[8]

- 1957 Creation of the Birds

- 1957 Women’s Tailor

- 1957 Caminos tortuosos (Winding Roads)

- 1957 Reflejo lunar (Moon Reflection)

- 1957 El gato helecho (Fern Cat)

- 1958 Celestial Pabulum[8]

- 1959 Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River'[8][17]

- 1959 Catedral vegetal

- 1959 Encounter

- 1959 Unexpected Presence"[8]

- 1960 Hacia la torre (Towards the Tower)

- 1960 Mimesis[8][18]

- 1960 Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst's Office'[8]

- 1960 Visit to the Plastic Surgeon’s

- 1961 Vampiro (Vampire)

- 1961 Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle

- 1961 Hacia Acuario (Towards Aquarius)

- 1962 Vampiros vegetarianos - sold for $3,301,000 in May 2015[19][20]

- 1962 Fenómeno (Phenomenon)

- 1962 Spiral Transit

- 1963 Naturaleza muerta resucitando (Still Life Resurrecting)

- 1963 Still Life Reviving'[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Arias-Jirasek, Rita, ed. (2008). Women Artists of Modern Mexico: Mujeres artistas en el México de la modernidad/Frida’s Contemporaries:Las contemporáneas de Frida (in English and Spanish). Alejandro G. Nieto, Christina Carlos and Veronica Mercado. Chicago/Mexico City: Frida National Museum of Mexican Art/museo Mural Diego Rivera. p. 165. ISBN 9781889410050.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lupina Lara Elizondo. Visión de México y sus Artistas Siglo XX 1901-1950. Mexico City: Qualitas. pp. 216–219. ISBN 9685005583.

- 1 2 3 4 Hayne, Deborah J. (Summer 1995). "The Art of Remedios Varo: Issues of Gender Ambiguity and Religious Meaning". Woman's Art Journal. 16 (1): 27. doi:10.2307/1358627. JSTOR 1358627.

- ↑ "Biografía – Remedios Varo Remedios Varo". remedios-varo.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- ↑ Kaplan, Janet A. (1988). Unexpected Journeys: The Art and Life of Remedios Varo. Abbeville Press. ISBN 9780896597976.

- 1 2 3 4 Kaplan, Janet A. (Fall 1980). "Remedios Varo: Voyages and Visions". Woman's Art Journal. 1 (2): 13. doi:10.2307/1358078. JSTOR 1358078.

- 1 2 3 Kaplan, Janet (1980-01-01). "Remedios Varo: Voyages and Visions". Woman's Art Journal. 1 (2): 13–18. doi:10.2307/1358078. JSTOR 1358078.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kaplan, Janet A. (Spring 1987). "Remedios Varo". Feminist Studies. 13 (1): 38–48. doi:10.2307/3177834. JSTOR 3177834.

- ↑ Angier, Natalie (2000-04-11). "Scientific Epiphanies Celebrated on Canvas". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ↑ González, María José (2018). "On the True exercise of Witchcraft" in the Work of Remedios Varo, in Surrealism, Occultism and Politics. New York: Routledge. pp. 194–209. ISBN 978-1-138-05433-2.

- ↑ Wolfgang Paalen, Le plus ancien visage du Nouveau Monde, in: Cahiers d´Art, Paris 1952.

- ↑ Arcq, Teresa (2008). Five Keys to the Secret World of Remedios Varo. Mexico City: Artes de México,. pp. 21–87.

- ↑ Raaij, Stefan van (2010). Surreal friends: Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Kati Horna. Burlington, VT: Farnham: Lund Humphries. ISBN 978-1848220591.

- ↑ Congdon, Kristen; Hallmark, Kara Kelley (2002). Artists from Latin American Cultures: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 292. ISBN 9780313315442. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ Pynchon, Thomas (1966). the crying of lot 49. Philadelphia: Lippincott. pp. 20–21. ISBN 9788424502041.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "Mimetismo, 1960. – Remedios Varo Remedios Varo". remedios-varo.com. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ "'My highlight of the year' — Vampiros Vegetarianos by Remedios Varo". christies.com.

Further reading

- Arias-Jirasek, Rita, ed. (2008). Women Artists of Modern Mexico: Mujeres artistas en el México de la modernidad /Frida’s Contemporaries:Las contemporáneas de Frida (in English and Spanish). Alejandro G. Nieto, Christina Carlos and Veronica Mercado. Chicago/ Mexico City: National Museum of Mexican Art /Museo Mural Diego Rivera. ISBN 9781889410050.

- Rosa J. H. Berland (2010). "Remedios Varo's Mexican Drawings". The Journal of Surrealism in the Americas. Arizona State University. 4 (1): 31–42.

- Rosa J. H. Berland, Remedios Varo: The Spanish Work. New Perspectives on the Spanish Avant-garde (1918-1936), Rodopi, Amsterdam, 2015

- Janet A. Kaplan, Unexpected Journeys: The Art and Life of Remedios Varo (New York: Abbeville, 1988), p. 164.

- Varos, Remedios (1997). Cartas, sueños y otros textos. Mexico: Universidad Autonoma de Tlaxcala. p. 13. ISBN 968-411-394-3.

- Ricardo Ovalle et al. (1994). Remedios Varo: Catálogo Razonado = Catalogue Raisonné. Ediciones Era, 342 pp. ISBN 968-411-363-3.

- O’Rawe, Ricki. ‘Ruedas metafísicas: “Personality” and “Essence” in Remedios Varo’s Paintings’. Hispanic Research Journal. 15.5 (2014): 445–62. https://dx.doi.org/10.1179/1468273714Z.000000000100

- O'Rawe, R. & Quance, R.A., (2016). Crossing the Threshold: Mysticism, Liminality, and Remedios Varo’s Bordando el manto terrestre (1961–62). Modern Languages Open. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.138

- Hayne, Deborah J. "The Art of Remedios Varo: Issues of Gender Ambiguity and Religious Meaning." Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1995), pp. 26–32. Woman’s Art Inc. (Accessed 10.2307/1358627). https://www.jstor.org/stable/1358627.

- Kaplan, Janet A. (Spring 1987). "Remedios Varo". Feminist Studies. 13 (1): 38–48. doi:10.2307/3177834. JSTOR 3177834.

- Kaplan, Janet A. (Fall 1980). "Remedios Varo: Voyages and Visions". Woman's Art Journal. 1 (2): 13. doi:10.2307/1358078. JSTOR 1358078.

- Zamora, Lois Parkinson (Spring 1992). "The Magical Tables of Isabel Allende and Remedios Varo". Comparative Literature. Duke University Press/University of Oregon, accession 10.2307/1770341. 44 (2): 113–143. JSTOR 1770341.

- "Remedios Varo". National Museum of Women in the Arts. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- de Orellana, Margarita ed. Five Keys to the Secret World of Remedios Varo. México City: Artes de México, 2008.

- Kaplan, Janet. "Remedios Varo: Voyages and Visions." Women's Art Journal 1.2 (1981): 13-18.

- Angier, Natalie. “Scientific Epiphanies Celebrated on Canvas.” The New York Times, 11 Apr. 2000, www.nytimes.com/2000/04/11/science/scientific-epiphanies-celebrated-on-canvas.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Remedios Varo. |

- Remedios Varo on Wikiart.org

- Biography

- Remedios Varo Bibliography

- Remedios Varo: Major Works

- Remedios Varo—A Compendium of Online Galleries, Biographies, Articles, and Miscellany

- Chronology of Remedios Varo

- Comprehensive Gallery of paintings by Remedios Varo (Language: Spanish)

- Association des amis de Benjamin Péret (Language: French)

- National Museum of Women in the Arts, Remedios Varo Artist Profile