Reform War

| Reform War or Mexican Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Benito Juarez Jesus Gonzalez Ortega Ignacio Zaragoza |

Felix Zuloaga Miguel Miramon Leonardo Marquez | ||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Mexico |

|

|

Spanish rule |

| Timeline |

|

|

The War of Reform (Spanish: Guerra de Reforma) in Mexico, during the Second Federal Republic of Mexico, was the three-year civil war (1857 - 1860) between members of the Liberal Party who had taken power in 1855 under the Plan of Ayutla, and members of the Conservative Party resisting the legitimacy of the government and its radical restructuring of Mexican laws, known as La Reforma. The War of the Reform is one of many episodes of the long struggle between Liberal and Conservative forces that dominated the country’s history in the 19th century. The Liberals wanted to eliminate the political, economic, and cultural power of the Catholic church as well as undermine the role of the Mexican Army. Both the Catholic Church and the Army were protected by corporate or institutional privileges (fueros) established in the colonial era. Liberals sought to create a modern nation-state founded on liberal principles. The Conservatives wanted a centralist government, some even a monarchy, with the Church and military keeping their traditional roles and powers, and with landed and merchant elites maintaining their dominance over the majority mixed-race and indigenous populations of Mexico.

This struggle erupted into a full-scale civil war when the Liberals, then in control of the government after ousting Antonio López de Santa Anna, began to implement a series of laws designed to strip the Church and military—but especially the Church—of its privileges and property. The liberals passed a series of separate laws implementing their vision of Mexico, and then promulgated the Constitution of 1857, which gave constitutional force to their program. Conservative resistance to this culminated in the Plan of Tacubaya, which ousted the government of President Ignacio Comonfort in a coup d'etat and took control of Mexico City, forcing the Liberals to move their government to the city of Veracruz. The Conservatives controlled the capital and much of central Mexico, while the rest of the states had to choose whether to side with the Conservative government of Félix Zuloaga or Liberal government of Benito Juárez.

The Liberals lacked military experience and lost most of the early battles, but the tide turned when Conservatives twice failed to take the liberal stronghold of Veracruz. The government of U.S. President James Buchanan recognized the Juárez regime in April 1859 and the U.S. and the government of Juárez negotiated the McLane-Ocampo Treaty, which if ratified would have given the Liberal regime cash but also granted the U.S. transit rights through Mexican territory. Liberal victories accumulated thereafter until Conservative forces surrendered in December 1860. While the Conservative forces lost the war, guerrillas remained active in the countryside for years after, and Conservatives in Mexico would conspire with French forces to install Maximilian I as emperor during the following French Intervention in Mexico.

Liberals vs. Conservatives in post-Independence Mexico

After the end of the Mexican War of Independence, the country was strongly divided as it tried to recover from more than a decade of fighting. From 1821-57, 50 different governments ruled the country. These included dictatorships, constitutional republican governments and a monarchy.[2]

The political division was roughly divided into two groups, the Liberals and the Conservatives. The Liberal political movements had their beginnings in the secret meetings of the Freemasonry. The secret nature of the society allowed for discreet political discussion. Conservatives favored a strong centralized government, with many wanting a European-style monarchy.[3]

Conservatives favored protecting many of the institutions inherited from the colonial period, including tax and legal exemptions for the Catholic Church and the military. Liberals favored the establishment of a federalist republic based on ideas coming out of the European Enlightenment, and the limiting of the Church’s and military’s privileges. Until the end of the Reform period Mexico’s history would be dominated by these two factions vying for control and fighting against foreign incursions at the same time.[3] The Reform Era of Mexican history is generally defined from 1855-76.[4]

Ascendency of the Liberals in the 1850s

In the 1850s the Liberal ousted Antonio López de Santa Anna under the Plan of Ayutla in 1855, bringing Juan Álvarez of the state of Guerrero to the presidency. Liberals exiled to the U.S. during the late Santa Anna regime, Melchor Ocampo and Benito Juárez returned to Mexico, and other Liberals came to national prominence, including Miguel Lerdo de Tejada and his younger brother, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. This ascendancy came after the loss of about half of Mexico’s national territory to the US in the Mexican–American War. Liberals believed that the entrenched power of the Roman Catholic Church and the military were the source of most of Mexico's problems.[4]

The Liberals' challenge to the Catholic Church's hegemony in Mexico came about in stages even before the 1850s. State-level measures adopted since the 1820s and the reform measures of during the regime of Valentín Gómez Farías led conservatives to defend Mexico's Catholic identity, including integration of Church and State. This included Catholic newspapers such as La Cruz and conservative groups that strongly attacked Liberal policies and ideology. This ideology had roots in the European Enlightenment, which sought to reduce the role of the Catholic Church in society. The Reforms began in the 1830s and 1840s coalesced into the principal laws of the Reform era, which were passed in two phases, from 1855–57 and then from 1858–60. The 1857 Constitution of Mexico was promulgated near the end of the first phase. More Reform laws were passed from 1861–63 and after 1867 when the Liberals emerged victorious after two civil wars with Conservative opponents.[5]

The Liberal Reform

The success of the Plan of Ayutla brought rebel Juan Álvarez to the Mexican presidency. Alvarez was a "puro" and appointed other radical Liberals to important posts, including Benito Juárez as Minister of Justice, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada as Minister of Development and Melchor Ocampo as Minister of Foreign Affairs. The first of the Liberal Reform Laws were passed in 1855. The Juárez Law, named after Benito Juárez, restricted clerical privileges, specifically the authority of Church courts,[6] by subordinating their authority to civil law. It was conceived of as a moderate measure, rather than abolishing church courts altogether. However, the move opened latent divisions in the country. Archbishop Lázaro de la Garza (es) in Mexico City condemned the Law as an attack on the Church itself, and clerics went into rebellion in the city of Puebla in 1855–56.[7] Other laws attacked the privileges traditionally enjoyed by the military, which was significant since the military had been instrumental in putting and keeping Mexican governments in office since Emperor Agustín de Iturbide in the 1820s.[6]

The next Reform Law was called the Lerdo law, after Miguel Lerdo de Tejada. Under this new law the government began to confiscate Church land.[6] This proved to be considerably more controversial than the Juárez Law. The purpose of the law was to convert lands held by corporate entities such as the Church into private property, favoring those who already lived on it. It was thought that this would encourage development and the government could raise revenue by taxing the process.[7] Lerdo de Tejada was the Minister of Finance and required that the Church sell much of its urban and rural land at reduced prices. If the Church did not comply, the government would hold public auctions. The Law also stated that the Church could not gain possession of properties in the future. However, the Lerdo law did not apply only to the Church. It stated that no corporate body could own land. Broadly defined, this would include ejidos, or communal land owned by Indian villages. Initially, these ejidos were exempt from the law, but eventually Indian communities suffered an extensive loss of land.[6]

By 1857 additional anti-clerical legislation, such as the Iglesias law (named after José María Iglesias), regulated the collection of clerical fees from the poor and prohibited clerics from charging for baptisms, marriages or funeral services.[8] Marriage became a civil contract, although no provision for divorce was authorized. Registry of births, marriages and deaths became a civil affair, with President Benito Juárez registering his newly-born son in Veracruz. The number of religious holidays was reduced and several holidays to commemorate national events introduced. Religious celebrations outside churches was forbidden, use of church bells restricted and clerical dress was prohibited in public.[9]

One other significant Reform Law was the Law for the Nationalization of Ecclesiastical Properties, which would eventually secularize nearly all of the country's monasteries and convents. The government had hoped that this law would bring in enough revenue to secure a loan from the US, but sales would prove disappointing from the time it was passed all the way to the early 20th century.[9]

As these laws were being passed, Congress debated a new Constitution. Delegates were concerned with the precedents established by the first of the Reform Laws and the issue of whether Mexico would have a central, authoritarian government or a federal republic. In the end, the Constitution of 1857 established a centralist component.[6] Since the constitution did not establish the Catholic Church as the official and exclusive religious institution, it was a major step in the separation of church and state.[9]

Civil war

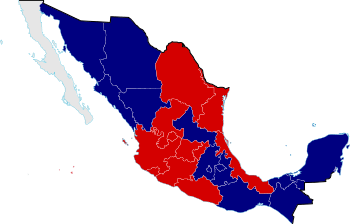

| Map |

|---|

|

|

Each of the Reform Laws met strong resistance from Conservatives, the Church and the military, culminating in military action and war. After the Juárez Law, General Tomás Mejía (1820 – 1867) rebelled against the Liberal government in the defense of the Catholic identity of Mexico in the Sierra Gorda region of Querétaro. Mejía would conduct operations against Liberal forces for the next eight years.[7]

Opposition to the Lerdo Law and the 1857 Constitution culminated in a takeover of Mexico City by Conservative forces. This operation was called the Plan of Tacubaya. When the military took control of Mexico City, then president Ignacio Comonfort agreed to the Plan’s terms, but Benito Juárez, then president of the Supreme Court, defended the 1857 Constitution. Juárez was arrested.[10] Comonfort was subsequently forced to resign and Gen. Félix Zuloaga was put in his place. After arriving in Mexico City, Zuloaga’s supporters closed Congress and arrested liberal politicians, preparing to write a new constitution for the country.[11]

The Plan of Tacubaya deeply divided the country, with each state deciding whether to support the Liberals' 1857 Constitution or the Conservatives' takeover of Mexico City. Juárez escaped prison and fled to the city of Querétaro.[10] He was recognized as the Liberals' interim president. As Zuloaga and the army took over more of the central part of Mexico, Juárez and his government were forced to the city of Veracruz. From there the Liberal government had control over the state of Veracruz and a number of allied states in the north and central-west. The Liberal government would be located in Veracruz from 1858-61.[12]

Full hostilities between Liberal and Conservative forces raged from 1858-60. The Conservatives controlled Mexico City, but not Veracruz. Twice in 1860 Conservative forces under Gen. Miguel Miramón tried to take the city but failed. From there Juárez directed the opposition movement, from which the Liberals obtained supplies and money through duties received in the port city.[13]

At the beginning of the war Liberal leaders and armies lacked the military experience of the Conservatives, who were backed by Mexico’s official military. However, as hostilities continued, Liberal forces gained experience and obtained aid from the US that would eventually enable victories for the Liberal side. On March 6 of that year, two ships previously acquired by the Conservative government were prevented from entering the city by a US naval force, acting in support of the Liberal faction of Benito Juarez. The force fleet attacked the Mexican ships and arrested their crews, eventually kidnapping Mexican marines and taking them to New Orleans.[14] This incident is known as the Battle of Anton Lizardo. In the same year Conservative forces were defeated in Oaxaca and Guadalajara. In December 1860 Gen. Miramón surrendered outside of Mexico City. Liberal forces reoccupied the capital on 1 January 1861, with Benito Juárez joining them a week later.[13] Despite the Liberals regaining control of the capital, bands of Conservative guerrillas operated in rural areas. Miramón went into exile to Cuba and Europe. However, Gen. Márquez remained active and Mejía operated from his stronghold in the Sierra Gorda until the end of the French Intervention in Mexico.[15]

The Juárez government up to the French Intervention

Juárez’s interim presidency was confirmed by his election in March 1861. However, the Liberals' celebrations of 1861 were short-lived. The war had severely damaged Mexico’s infrastructure and crippled its economy. While the Conservatives had been defeated, they would not disappear and the Juárez government had to respond to pressures from these factions. One of these concessions was amnesty to captured Conservative guerrillas who were still resisting the Juárez government, even though these same guerrillas were executing captured Liberals, one of whom was Melchor Ocampo. Juárez also faced external pressures from countries such as Great Britain, Spain and France owing to the large amounts indebted to them by Mexico.[16] Conservative factions in Mexico, who still wanted a European-style monarchy, would eventually conspire with the French government to install Mexico’s second emperor during the French Intervention in Mexico.[16][17]

See also

- La Reforma

- Constitution of 1857

- French intervention in Mexico

- Mexican–American War

- Pastry War

- List of wars involving Mexico

Battles in the Reform War:

Notes

- ↑ "Juárez es apoyado por tropas de EU en Guerra de Reforma" [Juarez is aided by U.S. troops in the War of Reform] (in Spanish). Mexico: El Dictamen. 2012-10-08. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02.

- ↑ Kirkwood 2000, p. 107

- 1 2 Kirkwood 2000, p. 109

- 1 2 Kirkwood 2000, p. 100

- ↑ Hamnett 1999, p. 160

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kirkwood 2000, p. 101

- 1 2 3 Hamnett 1999, p. 162

- ↑ Kirkwood 2000, pp. 101–102

- 1 2 3 Hamnett 1999, pp. 163–164

- 1 2 "La Guerra de Reforma, Historia de México" [The Reform War, History of Mexico] (in Spanish). Mexico: Explorando Mexico. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ Kirkwood 2000, p. 102

- ↑ Hamnett 1999, p. 163

- 1 2 Kirkwood 2000, p. 103

- ↑ "Juárez es apoyado por tropas de EU en Guerra de Reforma" [Juarez is aided by U.S. troops in the War of Reform] (in Spanish). Mexico: El Dictamen. 2012-10-08. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02.

- ↑ Hamnett 1999, p. 165

- 1 2 Kirkwood 2000, p. 104

- ↑ Hamnett 1999, p. 166

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reform War. |