MAX Light Rail

| |||

A westbound Type 2 Blue Line train seen crossing the Steel Bridge in Portland | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Locale | Portland, Oregon, U.S. | ||

| Transit type | Light rail | ||

| Number of lines | 5 | ||

| Number of stations | 97 | ||

| Daily ridership | 123,200 (as of 2017)[1] | ||

| Annual ridership | 39,699,760 (as of 2017)[1] | ||

| Website | MAX Light Rail | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | September 5, 1986 | ||

| Operator(s) | TriMet | ||

| Number of vehicles | 145[2] | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 60 mi (96.6 km)[2] | ||

| Track gauge |

4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) (standard gauge) | ||

| Electrification |

750 V DC 825 V DC | ||

| |||

MAX Light Rail (for Metropolitan Area Express), locally referred to as MAX or the MAX, is a light rail system that primarily serves the city of Portland, Oregon, United States. Owned and operated by TriMet, it consists of five lines and 97 stations over 60 miles (96.6 km) of track that connect three of Portland's neighborhoods—North, Northeast, and Southeast—and five suburban communities—Beaverton, Clackamas, Gresham, Hillsboro, and Milwaukie—to downtown Portland. Fed by regional bus services and a commuter rail line, the system had an average weekday ridership of 123,200 in 2017.

The MAX was conceived as a result of freeway revolts that took place in the early 1970s. The construction of its first line, then known as the Banfield light rail project, was completed in 1986. The system has since expanded through subsequent projects, with the Orange Line being its latest extension. From MAX's inception to 2004, about $3 billion was invested in light rail in Portland.[3]

History

Early beginnings

.jpg)

In the mid-1970s, Tri-Met began a study for light rail using funds intended for the canceled Mount Hood Freeway and Interstate 505,[4] which were made available by the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act in 1973.[5] The proposal became known as the Banfield light rail project, named for the Banfield Freeway—a segment of Interstate 84—that part of the alignment followed. The Tri-Met board approved the project in September 1978.[6] Construction of the 15.1-mile (24.3 km) route started in March 1982,[7] and the system opened on September 5, 1986.[8] Of the project's total cost of $214 million (equivalent to $955 million in 2016 dollars), 83 percent was funded by the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (now known as the Federal Transit Administration).[9] Less than two months before opening, Tri-Met adopted the name Metropolitan Area Express, or MAX, for the new system following an employee contest.[10]

As the planning of a second light rail line to the west side gained momentum in the late 1980s, the original MAX line came to be referred to as Eastside MAX, so as to distinguish it from the Westside MAX project.[11] Early proposals called for the westside extension to terminate at 185th Avenue, just west of the border between Hillsboro and Beaverton.[12] Staunch lobbying by Hillsboro and state officials led by Mayor Shirley Huffman pushed the line further west to downtown Hillsboro in 1993.[13] Construction of the 18-mile (29 km) line began in August 1993.[14] The extension opened in two stages: from downtown to Kings Hill/Southwest Salmon Street station in 1997, and then to Hatfield Government Center station, its present western terminus, the following year.[15] The resulting 33-mile (53 km) line began operating as a single, through route on September 12, 1998.[16] It became known as the Blue Line in 2001, after Tri-Met adopted color designations for its separate light rail routes.[17]

South–North proposal

Metro began studying a north–south light rail line in January 1992.[18] Early proposals projected a route to run from Hazel Dell, Washington south to Clackamas Town Center and Oregon City.[19][20] Tri-Met formally named the porposal South–North line to acknowledge Clackamas County's support of the region's past light rail projects.[21] In November 1994, Tri-Met introduced a $475-million ballot measure to fund the line's share in Oregon that received 63-percent support from voters.[21] Clark County voters subsequently rejected Washington's portion in February 1995,[22] prompting Tri-Met to downsize the plan and abandon the Clark County and North Portland segments up to the Rose Quarter.[23] In August 1995, the Oregon House of Representatives approved a $750-million transportation package that included $375 million for the scaled-back light rail line,[24] but opponents forced a statewide vote that defeated it in November 1996.[25]

Following the proposal's defeat, surveys conducted with local leaders in December 1996 revealed that the region remained in support of light rail.[26] A new proposal followed, placing the line between Lombard Street in North Portland and Clackamas Town Center.[27] In early 1997, Metro and Tri-Met proposed building the line without contributions from either Clark County or the state; funding would be sourced from Clackamas County and Portland instead. The proposal drew opposition from Milwaukie residents and forced a campaign that recalled the Milwakie mayor and city council in December 1997. In August 1998, Tri-Met placed another ballot measure to reaffirm voter support for the originally-approved $475-million funds.[21] The measure failed by 52 percent in November 1998, effectively canceling plans to build the proposed line.[28]

Later extensions

In 1997, Bechtel submitted an unsolicited proposal to design and build the planned extension to Portland International Airport in exchange for development rights to the Portland International Center—later renamed Cascade Station. A public–private partnership, the Airport MAX project commenced in 1999 and opened as the Red Line in September 2001.[29] In 1999, North Portland residents expressed their desire for what remained of the South–North plan, prompting officials to move forward with the Interstate MAX project that broke ground in 2000 and completed in May 2004;[21] it was designated the Yellow Line and initially ran from Expo Center in North Portland to 11th Avenue in downtown Portland, following the Blue and Red line alignment westward from the east end of the Steel Bridge. In 2001, Metro conducted two studies that revisited light rail in Clackamas County: one from Gateway Transit Center to Clackamas Town Center via Interstate 205, and the other from downtown Portland to Milwaukie via the Hawthorne Bridge.[30] Both proposals were approved in 2003.[31][32] The I-205/Portland Mall light rail project began in January 2007 with the reconstruction of the Portland Transit Mall.

Infrastructure

Lines

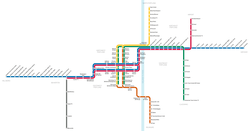

The MAX system currently consists of five lines, each designated by a color.

| Line | Opened | Last extension | Stations | Length | Termini | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Line[33] | September 5, 1986 | 1998 | 51 | 32.7 mi (52.6 km)[34][35] | Hatfield Government Center | Cleveland Avenue |

| Green Line[36] | September 12, 2009 | — | 30 | 15 mi (24.1 km)[37] | PSU South | Clackamas Town Center TC |

| Orange Line[38] | September 12, 2015 | — | 17 | 9.1 mi (14.6 km)[37][39] | Union Station | Southeast Park Avenue |

| Red Line[40] | September 10, 2001 | 2003 | 29 | 19.9 mi (32.0 km)[41] | Beaverton TC | Portland International Airport |

| Yellow Line[42] | May 1, 2004 | 2009 | 17 | 7.6 mi (12.2 km)[37][43] | Expo Center | PSU South |

Stations

The MAX system currently has a total of 97 stations. Of these, 51 stations are served by the Blue Line, 29 by the Red Line, 28 by the Green Line, 17 by the Orange Line, and 17 by the Yellow Line. 32 stations are served by two lines and 8 stations are served by three lines. The system's central stations encompass Pioneer Courthouse on the Portland Transit Mall and Pioneer Courthouse Square. All lines except for the Orange Line pass through the Rose Quarter and cross the Steel Bridge, although conversely the Orange Line is the only MAX line that travels across Tilikum Crossing.[44]

TriMet commissioned Zimmer Gunsul Frasca to design the system's 27 original stations, which earned the firm a Progressive Architecture Award in 1984.[45] MAX stations vary in size, but are generally simple and austere. As is typical of light rail systems, there are no faregates or specially segregated areas. Stations outside of downtown have platforms and entrance halls, while most stations in downtown are little more than streetcar-style stops. Official concessionaires sometimes open coffee shops at stations.

Fares

MAX stations do not have ticket barriers and rely on rider proof-of-payment.[46] On all of its services including the MAX, TriMet employs an automated fare collection system through a stored-value, contactless smart card called Hop Fastpass.[47] A physical Hop card can be purchased from retail stores for $3,[48] while a free, virtual version is available for Android users.[49] Alternatively, chip-embedded, single use tickets can be purchased from ticket vending machines located on or near station platforms.[50] Smartphones with a debit or credit card loaded into Google Pay, Samsung Pay, or Apple Pay can be used as well.[51] Portland Streetcar ticket vending machines also issue 2½-hour tickets and 1-day passes that are valid on the MAX.[52]

Prior to each boarding, riders must tap their fare medium to a card reader found at every station.[48] Fares are flat rate and are capped based on usage.[53] Riders may transfer to other TriMet services, C-Tran, and the Portland Streetcar using Hop Fastpass.[54]

| Rider | 2½-hour ticket | Day Pass | Month Pass† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | $2.50 | $5 | $100 |

| Youth, Honored Citizen | $1.25 | $2.50 | $28 |

| Note: † Available for Hop card and virtual Hop card only. Source: TriMet[54] | |||

History

From the MAX system's opening until 2012, riding was free in Fareless Square (known as the Free Rail Zone from 2010 to 2012), which included all of downtown and, starting in 2001, part of the Lloyd District. The 37-year-old fare-free zone was discontinued on September 1, 2012, as part of systemwide cost-cutting measures.[55] As part of the same budget cuts, TriMet discontinued its zonal fares, moving to a flat fare system. Zones had been in place since 1986, with higher fares for longer rides, and three fare zones (five until 1988).[55]

Original line and expansions

The MAX system was built in a series of six separate projects, and each line runs over one or more of the previously opened segments. The use of colors to distinguish the separately operated routes was first adopted in 2000 and brought into use in 2001.[17] The 2004-opened Yellow Line originally followed the same routing in downtown Portland as the Red and Blue lines, along First Avenue, Morrison Street and Yamhill Street, but it was shifted to a new alignment along the Portland Transit Mall on August 30, 2009, introducing light rail service along the Mall.[56][57] The Green Line began serving the Mall on September 12, 2009.[56]

| Segment description | Date opened | Line(s) | End points | New stations |

Length | Construction | Cost | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mi) | (km) | ||||||||

| Eastside (Banfield)[58] | September 5, 1986 | All Lines | 31 (27 originally) |

15.1 | 24.3 | March 1982 – September 1986 | $214 million | ||

| Westside[59] | September 12, 1998 | Blue, Red | 20 | 17.6 | 28.3 | July 1993 – September 1998 | $963 million | ||

| Airport[60] | September 10, 2001 | Red | 4 | 5.6 | 9.0 | May 1999 – September 2001 | $125 million | ||

| Interstate Avenue[61] | May 1, 2004 | Yellow | 10 | 5.8 | 9.3 | November 2000 – May 2004 | $350 million | ||

| Portland Transit Mall | August 30, 2009 | Green, Orange, Yellow |

|

14 (7 per direction) | 1.8 | 2.9 | February 2007 – September 2009 | $575.7 million | |

| I-205[62] | September 12, 2009 | Green |

|

8 | 6.5 | 10.5 | |||

| Portland–Milwaukie[63] | September 12, 2015 | Orange | 10 | 7.3 | 11.7 | June 2011 – September 2015 | $1.49 billion | ||

| Total | 97 | 59.7 | 96 | ||||||

Future

Proposed extensions

Red Line Extension to Washington County Fair Complex (Beaverton TC – Fair Complex/Hillsboro Airport):

- Projected opening: 2021

- Route: From the Red Line terminus at Beaverton Transit Center to the Washington County Fair Complex in Hillsboro via existing Blue Line track serving 10 existing stations. On the east side, TriMet would reconfigure the Red Line approach and add a second platform to Gateway Transit Center Station.[64]

Downtown Portland – Tualatin (Lincoln Street/SW 3rd – Bridgeport Village):

- Projected opening: 2025[65]

- Route: From PSU to Tualatin via Tigard along dedicated lanes on Barbur Boulevard.[66] In May 2016, light rail was chosen as the mode over bus rapid transit,[67] with the project expected to cost $2.5 billion.[68] Proposals to serve Marquam Hill/OHSU, Hillsdale, and PCC Sylvania with tunnels were dropped from the plan because they would be costly, have severe construction impacts, and attract few new transit riders.[69] Connecting OHSU to a surface transit line though elevators or escalators is being studied.[70] As of June 2018, the Southwest Corridor project is expected to cost $2.64 to $2.86 billion to construct.[71]

Cancelled extensions

Yellow Line Extension to Vancouver, WA (Expo Center – Marshall Center/Clark College):

- Former projected opening: 2019; length: 2.9 miles (4.7 km); stations: 5

- Route: From Expo Center to Clark College in Vancouver. This Yellow Line extension would have served Hayden Island and Vancouver, and initial planning for it took place in conjunction with the Columbia River Crossing project. Tracks in Vancouver would have been laid out as a northbound and southbound couplet on Broadway and Washington, respectively. This couplet would have merged onto 17th before terminating at Clark College. In February 2010, it was projected that construction could begin in 2014 for the Washington segment, 2015 for the Oregon segment.[72] In March 2014, the extension was canceled along with the Columbia River Crossing after the State of Washington pulled out of the project and the Oregon Legislature voted against the state continuing to fund it solely.[73]

Other extensions

TriMet has indicated that additional extensions have been studied or discussed with Metro and cities in the region.[74][75] These proposed extensions include the following, with light rail being considered along with other alternatives:

- Extension of either the Orange Line from Milwaukie and/or the Green Line from Clackamas Town Center to Oregon City[74]:67

- Extension of the Blue Line from Hillsboro to Forest Grove[74]:67

- Constructing a subway tunnel under downtown Portland[76]

Operations

In parts of the MAX system, particularly in central Portland and Hillsboro, MAX trains run on surface streets. Except on the Portland Transit Mall, trains run in reserved lanes closed to other motorized vehicles. On the Transit Mall, trains operate on the same lanes as TriMet buses (although MAX trains have traffic priority). Elsewhere, MAX runs within its own exclusive right-of-way, in street medians, alongside freeways, and on former freight railroad lines.

Where the tracks run in a street median, such as the majority of the Yellow Line and the section of the Blue Line along Burnside Avenue between Gateway Transit Center and Ruby Junction, intersections are generally controlled by traffic signals which give trains preemption. Where the tracks occupy a completely separate right-of-way, the tracks are protected by automated grade crossing gates. A three-mile (4.8 km) section consists of two tunnels below Washington Park. While this section has only one station, it is 260 feet (79 m) below ground level, making it the deepest transit station in North America[77] and one of the deepest in the world.

Because of Portland's relatively small 200-foot (61 m) downtown blocks, trains operate with only one or two cars (technically, the single-car "trains" are in fact not trains). The MAX cars are about 90 feet (27.4 m) long, so a stopped train consisting of more than two cars would block intersections. All service is typically operated with two-car trains, except for certain trips during late-night hours. During the first few years of Red Line and Yellow Line service, those lines normally used single cars on a portion of their service, but as ridership has grown and additional light rail cars have been acquired, those lines now normally use all two-car trains. The 2009-introduced MAX Mall Shuttle, which provided supplementary service along the Portland Transit Mall on weekday afternoons only, normally always used a single car;[56] it was discontinued in June 2011.[78]

The trains operate on direct current and utilize two voltages, 750 V DC nominal on sections west of NE 9th Avenue & Holladay Street and 825V DC nominal on the remainder. The two systems are electrically isolated.[79]

Trains run every 15 minutes from early in the morning until late at night, even on weekends. The Blue Line runs every 10 minutes during rush hour. Headways between trains are shorter in the central section of the system, where lines overlap. Actual schedules vary by location and time of day. At many stations, a live readerboard shows the destination and time-to-arrival of the next several trains, using data gathered by a vehicle tracking system.

Arrival information screens are in place at all stations on the Green Line and Transit Mall, with reader boards on the Yellow Line and some Red Line stations. These show arrival countdowns for trains and information about any service disruptions. After a $180,000 grant from the Federal Transit Administration, TriMet began adding digital displays to Blue and Red Line stations in 2013, initially on the west side, and then on the east side.[80] All MAX stations are expected to be fitted with screens by 2016.

Rolling stock

There are currently five models of MAX light rail vehicles, designated by TriMet as "Type 1", "Type 2", "Type 3", "Type 4" and "Type 5". All of the different types are used on all of the MAX lines.

Type 1

The Type 1 cars were manufactured by a joint venture between La Brugeoise et Nivelles and Bombardier Corporation before the latter acquired the former, and featured a raised floor with steps at the doors. These cars are based on a La Brugeoise et Nivelles design used in Rio de Janeiro Line 2.[81] The first vehicle was completed at the factory in late 1983[82] and arrived in Portland in 1984.[83] The Type 1 cars were delivered without air-conditioning, but it was added to all cars during a retrofit in 1997–98.

For their first 30 years, until 2016, the Type 1 cars had roll-type, printed destination signs. The Type 1 were the only MAX cars whose rollsigns were hand-cranked. Because of the time-consuming process to change the signs, only the sign on the exposed end of the car was changed to the correct destination. The side signs only listed the designated route color (such as "Blue Line") rather than a destination, and the sign on the coupled end of each car in a two-car train was left blank. A two-year program that began in October 2014[84] and was completed in September 2016 gradually replaced all of the rollsigns in the Type 1 cars (as well as those in the Types 2 and 3) with digital, LED-type destination signs.[85]

All Type 1 stock are currently undergoing a refurbishing. Once completed, all cars will be equipped with new HVAC systems and new brake resistors. Updating the rail-cars was chosen over replacing them due to cost.[86] The Type 1 cars are the only ones that lack a regenerative braking capability.[79]

Type 2

With the partial opening of Westside MAX in 1997, TriMet's "Type 2" light rail vehicles were introduced. The Siemens model SD660 (originally SD600, but retroactively redesignated SD660 in 1998[87]) have a low-floor design, a first for light rail vehicles in North America,[88][89] digital readerboards and a slightly more open floor plan. The floor is nearly level with the platforms, and small ramps called "bridge plates" extend (on request) from two of the four doors, enabling passengers in wheelchairs to roll on and off of the vehicle easily. These permitted the elimination of wheelchair lifts that had been located at every station and were time-consuming to use.[90] High-floor Type 1 cars are now always paired with a low-floor Type 2 or 3 car so that each train is wheelchair-accessible.

The first low-floor light rail vehicle was delivered in 1996[91] and first used in service on August 31, 1997.[90] The new vehicles also came equipped with air-conditioning, a feature originally lacking from the Type 1 vehicles.[88] The initial order of 39 Type 2 vehicles was expanded, in stages, to a total of 52 vehicles.[92]

Some of the later models of light rail vehicles had automatic passenger counters retrofitted; in these models, they are on the floor of the doorways.

In 2001–02, TriMet modified the interior of the Type 2 cars to add space for bicycles. Eight seats per vehicle were removed and replaced—in four places per car—with hooks from which a bicycle can be hung.[93] All later cars have been delivered from the manufacturer with these bike hooks already installed. In 2014–2016, the rollsign-type destination signs in these cars and the almost-identical Type 3 cars were gradually replaced with digital signs in a two-year conversion program.[85]

Type 3

The second series of Siemens SD660 cars, TriMet's "Type 3" MAX light rail vehicle, are outwardly identical to the Type 2 cars in design, the primary difference being various technical upgrades. Siemens installed an improved air-conditioning system, more ergonomic seats and automatic passenger counters using photoelectric sensors above the doorways. The Type 3 cars were the first to wear the transit agency's newer (2002-adopted) paint scheme. Purchased for the opening of the Yellow Line in May 2004, delivery of the Type 3 series began in February 2003, and the vehicles began to enter service in September 2003.[94]

Type 4

Twenty-two new Siemens S70 low-floor cars, designated Type 4, were purchased in conjunction with the I-205 and Portland Mall MAX projects. They feature a more streamlined design than previous models, have more seating and are lighter in weight and therefore more energy-efficient. They can only operate in pairs, since each car has just one operator's cab, at the "A" end (the "B" end has additional passenger seating). At about 95 feet (28.96 m) long, they are about three feet longer than Type 2 and Type 3 cars, which were 92 feet (28.04 m).[95] The Type 4 MAX cars began to enter service in August 2009.[96]

The Type 4 cars were the first to use LED-type destination signs. On the rollsign-type destination signs used—until 2016[85]—on the Type 1, 2 and 3 cars the designated route color (blue, green, red, or yellow) was shown as a colored background under white or black text, while in the LED signs the route color is indicated by a colored square at the left end of the display, and all text is orange lettering against a black background.[56] In October 2014, TriMet began a two-year program to gradually replace all rollsigns in its MAX fleet with LED signs, affecting a total of 105 cars (and four signs per car).[84] The conversion program was completed in September 2016 (with the last use of a rollsign in service being on August 19).[85]

Type 5

The second series of Siemens S70 cars, TriMet's "Type 5" MAX vehicle, were purchased in conjunction with the Portland–Milwaukie (MAX Orange Line) project, but are used on all lines in the system. These vehicles include some improvements over the Type 4 cars, including a less-cramped interior seating layout[97] and improvements to the air-conditioning system and wheelchair ramps.[98] TriMet placed the order for the Type 5 cars with Siemens in April 2012 and they began to be delivered in September 2014. The first two cars entered service on April 27, 2015,[99] and all but the last two had entered service by the time the Orange Line opened in September 2015.[100] The fleet numbers for the Type 5 cars are 521–538[101] (at the time the first cars were built, fleet numbers 511–514 were in use for the Vintage Trolley cars).

| Image | Designation | Car numbers | Manufacturer | Model No. | First used | No. of Seats/ Overall Capacity | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_-_Portland%2C_Oregon.jpg) | Type 1 | 101–126 | Bombardier | none | 1986 | 76/166 | 26 |

| Type 2 | 201–252 | Siemens | SD660 | 1997 | 64/166 | 52 |

| Type 3 | 301–327 | Siemens | SD660 | 2003 | 64/166 | 27 |

_(mulDA0008a).jpg) | Type 4 | 401–422 | Siemens | S70 | 2009 | 68/172[95] | 22 |

| Type 5 | 521–538 | Siemens | S70 | 2015 | 72/186[98] | 18 |

Notes on capacities:

- The capacities given are for a single car; a two-car train has double the capacity.

- The Type 2 cars originally had 72 seats, but eight seats were later removed, to make space for bicycles.[93]

- All of these capacity figures are based on "normal" loading conditions (defined as 4 standing passengers per square meter by industry standards[102]); under so-called "crush" loading conditions (6-8 standees per m2), all of these cars are capable of carrying many more passengers than stated here.

Former Vintage Trolley service

In addition to regular MAX service, the Portland Vintage Trolley operated on the MAX system from 1991 until 2014, on most weekends, serving the same stops. This service, which operated for the last time in July 2014,[103][104] used 1991-built replicas of 1904 Portland streetcars. Until 2009, the Vintage Trolley service followed a section of the original MAX line, between the Galleria/Library stations and Lloyd Center, but in September 2009 the service moved to the newly opened MAX alignment along the transit mall, running from Union Station to Portland State University,[56][105] and remained on that route in subsequent seasons. In 2011, the service was reduced to only seven or eight Sundays per year,[106] and in July 2014 it was discontinued entirely, with the sale of the two remaining faux-vintage cars to a group planning a streetcar line in St. Louis.[103][104]

See also

References

- 1 2 "TriMet Service and Ridership Statistics" (PDF). TriMet. October 5, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- 1 2 "TriMet At-A-Glance". TriMet. January 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ↑ Ozawa, Connie P., ed. (2004). The Portland Edge: Challenges and Successes in Growing Communities. Island Press. p. 19. ISBN 1-55963-695-5.

- ↑ Selinger 2015, p. 30.

- ↑ Selinger 2015, p. 20.

- ↑ Hortsch, Dan (September 27, 1978). "Tri-Met board votes to back Banfield light-rail project". The Oregonian. p. F1.

- ↑ Federman, Stan (March 27, 1982). "At ground-breaking: Festivities herald transitway". The Oregonian. p. A12.

- ↑ Koberstein, Paul (September 7, 1986). "Riders swamp light rail as buses go half-full and schedules go by the way". The Oregonian. p. A1.

- ↑ Federman, Stan (September 5, 1986). "All aboard! MAX on track; ride free". The Oregonian. p. A1.

- ↑ Anderson, Jennifer (May 5, 2006). "Stumptown Stumper". Portland Tribune. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Banfield Light Rail Eastside MAX Blue Line" (PDF). TriMet. July 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ United States. Federal Transit Administration (1994). Hillsboro Extension of the Westside Corridor Project, Washington County: Environmental Impact Statement (Report). Federal Transit Administration. p. P1–P5. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ↑ Hamilton, Don (February 23, 2000). "Shirley Huffman, fiery lobbyist, earns praise; Hard work and a sharp phone call put light-rail trains into downtown Hillsboro". The Oregonian. p. E2.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon (August 8, 1993). "Groundbreaking ceremonies set to launch project". The Sunday Oregonian. "Westside Light Rail: Making Tracks" (special section), p. R1.

- ↑ O'Keefe, Mark (September 1, 1997). "New MAX cars smooth the way for wheelchairs". The Oregonian. p. B12.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon; Hamilton, Don (September 9, 1998). "Go west young MAX". The Oregonian. p. C1.

- 1 2 Stewart, Bill (September 21, 2000). "Local colors roll out: Tri-Met designates the Blue, Red and Yellow lines". The Oregonian. pp. E1, E10.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon (March 7, 1993). "Decisions to be made soon on north–south light rail". The Oregonian. p. C4.

- ↑ Leeson, Fred (February 13, 1994). "Planners narrowing options for north–south light-rail line". The Oregonian. p. C5.

- ↑ McCarthy, Dennis (September 15, 1994). "Light-rail service? On to Oregon City!". The Oregonian. p. D2.

- 1 2 3 4 Selinger 2015, p. 80.

- ↑ Stewart, Bill (February 8, 1995). "Clark County turns down north–south light rail". The Oregonian. p. A1.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon; Stewart, Bill (March 1, 1995). "MAX may skip Clark County, N. Portland". The Oregonian. p. B1.

- ↑ Green, Ashbel S.; Mapes, Jeff (August 4, 1995). "Legislature is finally working on the railroad". The Oregonian. p. A1.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon; Hunsenberger, Brent (November 7, 1996). "Tri-Met still wants that rail line to Clackamas County". The Oregonian. p. D1.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon (December 12, 1996). "Survey revives light-rail plan". The Oregonian. p. B1.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon (February 12, 1997). "South–north light-rail issue keeps on going". The Oregonian. p. A1.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon (November 7, 1998). "South–north line backers find themselves at a loss after election day defeat". The Oregonian. p. B1.

- ↑ Selinger, Philip (2015). "Making History: 45 Years of Transit in the Portland Region" (PDF). TriMet. p. 82. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ↑ Rose, Joseph (May 8, 2001). "New MAX plan tries the double-team approach". The Oregonian. p. D1.

- ↑ Leeson, Fred (March 27, 2003). "TriMet board agrees to plan for southeast light-rail lines". The Oregonian. p. C2.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Laura (April 18, 2003). "Metro gives final OK to MAX lines". The Oregonian. p. D6.

- ↑ "MAX Blue Line Map and Sechdule". TriMet. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ↑ Morgan, Steve (November 1998). "US Vice-President Gore launches Portland's new Westside route". Tramways & Urban Transit. UK: Ian Allan Publishing. ISSN 1460-8324.

- ↑ TriMet Staff (November 26, 2014). "I'm running the entire MAX Blue Line in a 'TriMet ultramarathon'". TriMet. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ "MAX Green Line Map and Sechdule". TriMet. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Pantell, Susan (December 2009). "Portland: New Green Line Light Rail Extension Opens". Light Rail Now. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ "MAX Orange Line Map and Sechdule". TriMet. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Portland–Milwaukie MAX Orange Line" (PDF). TriMet. July 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ↑ "MAX Red Line Map and Sechdule". TriMet. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ↑ "Airport MAX Red Line" (PDF). TriMet. July 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ "MAX Yellow Line Map and Sechdule". TriMet. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ↑ "Interstate MAX Yellow Line Project History". TriMet. 2004. Archived from the original on June 3, 2004. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ↑ Rail System Map with transfers (PDF) (Map). TriMet. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ↑ Murphy, Jim (November 1986). "Portland transit system inaugurated". Progressive Architecture. Vol. 67. p. 25+.

- ↑ Rose, Joseph (March 20, 2015). "Fare turnstiles coming to Portland-Milwaukie MAX stations". The Oregonian. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ↑ "NXP helps the Portland-Vancouver Metro region move intelligence to the cloud with the new Hop Fastpass™ Transit Card used on Buses, the Light Rail and Streetcars". NXP Blog. October 9, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- 1 2 Altstadt, Roberta (February 8, 2018). "Major retailers continue selling paper tickets as Hop Fastpass™ rollout continues". TriMet News. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ↑ Altstadt, Roberta (April 16, 2018). "Portland's Virtual Hop Fastpass™ transit card now available to all Google Pay users". TriMet News. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ↑ Altstadt, Roberta (May 16, 2018). "Hop Fastpass™ fare system takes more leaps forward with ticket machine, retail store transitions". TriMet News. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ↑ Lum, Brian (August 22, 2017). "You Can Now Use Hop With Just Your Phone". How We Roll, TriMet. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Streetcar Fares". Portland Streetcar Inc. Retrieved September 3, 2012.

- ↑ Njus, Elliot (July 10, 2017). "Hop Fastpass: The pros and cons of TriMet's new e-fare system". The Oregonian. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- 1 2 "Hop fares". TriMet. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- 1 2 Bailey Jr., Everton (August 30, 2012). "TriMet boosts most fares starting Saturday; some routes changing". The Oregonian. Retrieved September 3, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Morgan, Steve (2010). "Expansion for Portland's MAX: New routes and equipment". Passenger Train Journal. White River Productions, Inc. 33 (1 – First quarter 2010): 38–40.

- ↑ "New MAX line opens downtown". Portland Tribune. August 28, 2009. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Eastside MAX Blue Line Project History". TriMet. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Westside MAX Blue Line Project History". TriMet. Archived from the original on March 31, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Airport MAX Red Line Project History". TriMet. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Interstate MAX Yellow Line Project History". TriMet. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "MAX Green Line Project History". TriMet. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Portland-Milwaukie Light Rail Project" (PDF). TriMet. June 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ↑ Howard, John (October 26, 2017). "TriMet considering expansion of MAX Red Line to county fairgrounds". Portland Tribune. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ↑ Beebe, Craig (May 10, 2016). "Leaders decide: Light rail for Portland to Bridgeport Village, no PCC tunnel". Metro News. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Southwest Corridor Plan". Metro. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Njus, Elliot (May 9, 2016). "Committee picks light rail for SW Corridor transit project". The Oregonian. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ↑ Haas, Ryan (November 8, 2016). "Tigard Voters Saying Yes To Light Rail Plan". Oregon Public Broadcasting. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ↑ Tims, Dana (July 14, 2015). "No deep tunnel for OHSU: Southwest Corridor plan". The Oregonian. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ Beebe, Craig (July 13, 2015). "Southwest Corridor leaders drop Marquam Hill/Hillsdale tunnels, leave door open on Sylvania option". Metro News. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ Mesh, Aaron (June 13, 2018). "The Price Tag on Light Rail to Bridgeport Village Has Grown by Nearly a Billion Dollars". Willamette Week. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Columbia River Crossing information packet". ODOT, WSDOT. February 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ↑ Manning, Jeff (March 7, 2014). "Columbia River Crossing: ODOT to pull plug, bridge project is dead". The Oregonian. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Transit Investment Plan FY 2012" (PDF). TriMet. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ↑ Rivera, Dylan (September 5, 2009). "MAX Green Line signals decades of rail growth". The Oregonian. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ↑ Njus, Elliot (June 14, 2017). "City planners float idea of subway tunnel through downtown Portland". The Oregonian. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Westside Light Rail MAX Blue Line extension (fact sheet)" (PDF). TriMet. November 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ↑ Rose, Joseph (June 3, 2011). "TriMet will make several seasonal bus line adjustments Sunday". The Oregonian. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- 1 2 "One Breakpoint is Enough: Traction Power Simulation in Portland" (PDF). Transportation Research Board. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ↑ Blevins, Drew (July 23, 2013). "We're adding arrival screens at more Blue and Red Line MAX stations". How We Roll. TriMet. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ↑ http://vfco.brazilia.jor.br/TU/MetroRio/Trem-VLT-Cobrasma-Pre-Metro-Rio-RJ.shtml

- ↑ "‘Roomy, good-looking’ light-rail cars please Tri-Met official" (November 27, 1983). The Sunday Oregonian, p. B5.

- ↑ "First car for light rail delivered" (April 11, 1984). The Oregonian, p. C4.

- 1 2 Tramways & Urban Transit magazine, March 2015, p. 121. UK: LRTA Publishing.

- 1 2 3 4 Tramways & Urban Transit magazine, November 2016, p. 440. UK: LRTA Publishing.

- ↑ Longeteig, Andrew (June 19, 2015). "Our Oldest MAX Trains are Getting Makeovers". HowWeRoll. TriMet. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ↑ Tramways & Urban Transit magazine, October 1998, p. 397. UK: Ian Allan Publishing/Light Rail Transit Association. ISSN 1460-8324.

- 1 2 Oliver, Gordon (April 15, 1993). "Tri-Met prepares to purchase 37 low-floor light-rail cars". The Oregonian, p. D4.

- ↑ Vantuono, William C. (July 1993). "Tri-Met goes low-floor: Portland's Tri-Met has broken new ground with a procurement of low-floor light rail vehicles. The cars will be North America's first low-floor LRVs." Railway Age, pp. 49–51.

- 1 2 O'Keefe, Mark (September 1, 1997). "New MAX cars smooth the way for wheelchairs". The Oregonian, p. B12.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon (August 1, 1996). "MAX takes keys to cool new model". The Oregonian, p. D1.

- ↑ Oliver, Gordon (September 26, 1997). "Tri-Met expands light-rail car order". The Oregonian, p. B6.

- 1 2 Stewart, Bill (August 20, 2001). "MAX will add racks for bikes, not bags". The Oregonian.

- ↑ Tramways & Urban Transit magazine, November 2003, p. 428. UK: Ian Allan Publishing/Light Rail Transit Association.

- 1 2 "MAX: The Next Generation". TriMet. Archived from the original on March 4, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ↑ Redden, Jim (August 6, 2009). "TriMet puts new light-rail cars on track". Portland Tribune. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ↑ Rose, Joseph (July 31, 2012). "TriMet asks cramped MAX riders to help design next-generation train's seating". The Oregonian. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- 1 2 "PMLR Type 5 LRV Fact Sheet" (PDF). TriMet. March 2015. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ↑ Tramways & Urban Transit magazine, July 2015, p. 289. UK: LRTA Publishing. ISSN 1460-8324.

- ↑ Tramways & Urban Transit magazine, November 2015, p. 450. UK: LRTA Publishing. ISSN 1460-8324.

- ↑ Tramways & Urban Transit magazine, June 2012, p. 235. UK: LRTA Publishing. ISSN 1460-8324.

- ↑ "Glossary section, Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual, 2nd Edition (TCRP Report 100)" (PDF). Transportation Research Board. October 2003. pp. 9 ("car weight designations"). Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- 1 2 "Vintage Trolley Has Ceased Operation". Portland Vintage Trolley website. September 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- 1 2 "Portland double-track is brought into use". Tramways & Urban Transit. LRTA Publishing. November 2014. p. 454.

- ↑ "Vintage Trolley 2012 Schedule on the Portland Mall". Portland Vintage Trolley website. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ↑ Tramways & Urban Transit, April 2011, p. 152. LRTA Publishing Ltd.

Work cited

- Selinger, Philip (2015). "Making History: 45 Years of Transit in the Portland Region" (PDF). TriMet. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to MAX light rail. |