Negro Fort

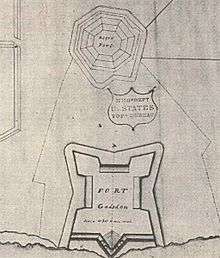

Negro Fort was a fort built by the British in 1814, during the War of 1812, on the Apalachicola River, in a remote part of Spanish Florida. It is part of the Prospect Bluff Historic Sites, in the Apalachicola National Forest, Franklin County, Florida.

The fort was called Negro Fort only after the British left in 1815, its later residents and staff were primarily blacks (free Negroes or fugitive slaves), together with some Choctaws. There were a significant number of maroons already in the area before the fort was built and beginning in 1804 there was for several years a store (trading post) there. The blacks, having worked on plantations, knew how to plant and care for crops, and also to care for domesticated animals, mostly cattle.

When withdrawing in 1815, the local British commander deliberately left the fully armed fort in the hands of the blacks – maroons or their descendants, some of them trained members of the former Colonial Marines – and their Creek allies. As Nicolls hoped, the fort became a center of resistance, near the Southern border of the United States. The site was militarily significant, although without artillery training, the blacks were ultimately unable to defend themselves. It is the largest and most famous instance before the American Civil War in which armed former or fugitive slaves fought whites who sought to return them to slavery. (A much smaller predecessor was Fort Mosé, near St. Augustine.) The fort was destroyed in 1816 at the command of General Andrew Jackson. The attackers used heated shot against the powder magazine and ignited it, blowing up the fort and killing over 270 people immediately. However, the area continued to attract escaped slaves until the construction of Fort Gadsden in 1818.

Negro Fort

The "Negro Fort", as it soon came to be called, became widely known. It offered a safe refuge to anyone who wished to flee from the United States, whether escaped slaves, who were safe once they reached Spanish Florida, or Native Americans. The proslavery press in the United States expressed outrage.[1]:49 This concern was published in the Savannah Journal:

It was not to be expected that an establishment so pernicious to the Southern states, holding out to a part of their population temptations to insubordination, would have been suffered to exist after the close of the war [of 1812]. In the course of last winter, several slaves from this neighborhood fled to that fort; others have lately gone from Tennessee and the Mississippi Territory. How long shall this evil, requiring immediate remedy, be permitted to exist?[2]

Escaped slaves came from as far as Virginia.[3]:178 The Apalachicola, as was true of other rivers of north Florida, was a base for raiders who attacked Georgia plantations, stealing anything portable and helping the slaves escape.

To guard this portion of the U.S. border, in April 1816 the U.S. Army decided to build Fort Scott, on the Flint River, a tributary of the Apalachicola. Supplying the fort, however, was a problem; to take materials overland would have required traveling through unsettled wilderness. The obvious route to supply the Fort was the river. Although technically this was Spanish territory, Spain had neither the resources nor the inclination to protect this remote area.

Put differently, the new Fort Scott meant that supplies in or men in or out went right in front of the Negro Fort. The boats carrying supplies for the new fort, the Semelante and the General Pike, were escorted by gunboats sent from Pass Christian. The defenders of the Fort ambushed sailors gathering fresh water, killing 3, and capturing one (who was subsequently burned alive); only one escaped.[4] When the U.S. boats attempted to pass the Fort on April 27 they were fired upon. [5][6] This event provided a casus belli for destroying Negro Fort.

Jackson requested permission to attack, and started preparations. Ten days later, Andrew Jackson ordered Brigadier General Edmund P. Gaines at Fort Scott to destroy Negro Fort. The U.S. expedition included Creek Indians from Coweta, who were induced to join by the promise that they would get salvage rights to the fort if they helped in its capture. On July 27, 1816, following a series of skirmishes, the U.S. forces and their Creek allies launched an all-out attack under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Duncan Clinch, with support from a naval convoy commanded by Sailing Master Jarius Loomis.

Secretary of State John Quincy Adams justified the attack and subsequent seizure of Spanish Florida by Andrew Jackson as national "self-defense", a response to Spanish helplessness and British complicity in fomenting the "Indian and Negro War." Adams produced a letter from a Georgia planter complaining about "brigand Negroes" who made "this neighborhood extremely dangerous to a population like ours." Southern leaders worried that the Haitian Revolution or a parcel of Florida land occupied by a few hundred blacks could threaten the institution of slavery.

On July 20, Clinch and Creek allies left Fort Scott to assault Negro Fort but stopped short of firing range realizing that artillery (gunboats) would be needed.

Battle of Negro Fort

The Battle of Negro Fort was the first major engagement of the Seminole Wars period and marked the beginning of General Andrew Jackson's conquest of Florida.[7]

Three leaders of the fort had come with Nicolls (since departed) from Pensacola. They were: Garçon ("boy"), 30, a carpenter and former slave in Spanish Pensacola, valued at 750 pesos ;[3]:181 Prince, 26, a master carpenter valued at 1,500 pesos, who had received wages and an officer's commission from the British in Pensacola;[3]:157 and Cyrus, 26, also a carpenter, and literate.[3]:181 Prince may be the military commander of the same name at the head of 90 free blacks brought from Havana to assist the Spanish defense in St. Augustine during the Patriot War of 1812.*

As the U.S. expedition drew near the fort on July 27, 1816, black militiamen had already been deployed and began skirmishing with the column before regrouping back at their base. At the same time the gunboats under Master Loomis moved upriver to a position for a siege bombardment. Negro Fort was occupied by about 330 people during the time of battle. At least 200 were maroons, armed with ten cannons and dozens of muskets. Some were former Colonial Marines.[8] They were accompanied by thirty or so Seminole and Choctaw warriors under a chief. The remaining were women and children, the families of the black militia.[7][5]

Before beginning an engagement General Gaines first requested a surrender. Garçon, the leader of the fort, a former Colonial Marine, refused. Garçon told Gaines that he had orders from the British military to hold the post and at the same time raised the Union Jack and a red flag to symbolize that no quarter would be given. The Americans considered the Negro Fort to be heavily defended; after they formed positions around one side of the post, the Navy gunboats were ordered to start the bombardment. Then the defenders opened fire with their cannons, but they had not been trained by the British to handle artillery, and thus were not effective.[7][5]

It was daytime when Master Jarius Loomis ordered his gunners to open fire. After five to nine rounds were fired to check the range, the first round of hot shot cannonball, fired by Navy Gunboat No. 154, entered the Fort's powder magazine. The ensuing explosion was massive, and destroyed the entire Fort. Almost every source states all but about 60 of the 334 occupants of the Fort were instantly killed, and others died of their wounds shortly after, including many women and children.[9] A more recent scholar says the number killed was "probably no more than forty", the remainder having fled before the attack.[10]:288 The explosion was heard more than 100 miles (160 km) away in Pensacola. Just afterward, the U.S. troops and the Creeks charged and captured the surviving defenders. Only three escaped injury; two of the three, an Indian and a Negro, were executed at Jackson's orders.[9] General Gaines later reported that

The explosion was awful and the scene horrible beyond description. You cannot conceive, nor I describe the horrors of the scene. In an instant lifeless bodies were stretched upon the plain, buried in sand or rubbish, or suspended from the tops of the surrounding pines. Here lay an innocent babe, there a helpless mother; on the one side a sturdy warrior, on the other a bleeding squaw. Piles of bodies, large heaps of sand, broken glass, accoutrements, etc., covered the site of the fort... Our first care, on arriving at the scene of the destruction, was to rescue and relieve [kill] the unfortunate beings who survived the explosion.

Garçon, the black commander, and the Choctaw chief, among the few who survived, were handed over to the Creeks, who shot Garçon and scalped the chief. African-American survivors were returned to slavery. There were no white casualties from the explosion.

The Creek salvaged 2,500 muskets, 50 carbines, 400 pistols, and 500 swords from the ruins of the fort, increasing their power in the region. The Seminole, who had fought alongside the blacks, were conversely weakened by the loss of their allies. The Creek participation in the attack increased tension between the two tribes.[11] Seminole anger at the U.S. for the fort's destruction contributed to the breakout of the First Seminole War a year later.[12]

Spain protested the violation of its soil, but according to historian John K. Mahon, it "lacked the power to do more."[13]

Aftermath

The largest group of survivors, including blacks from the surrounding plantations who were not at the Fort, took refuge further south, in Angola.[14]:232–233[10]:283–285 Some other refugees founded Nicholls Town in the Bahamas.[14]:129

Garçon was executed by firing squad because of his responsibility for the earlier killing of the watering party, and the Choctaw Chief was handed over to the Creeks, who scalped him. Some survivors were taken prisoner and placed into slavery under the claim that Georgia slaveowners had owned the ancestors of the prisoners.[15] Neamathla, a leader of the Seminole at Fowltown, was angered by the death of some of his people at Negro Fort so he issued a warning to General Gaines that if any of his forces crossed the Flint River, they would be attacked and defeated. The threat provoked the general to send 250 men to arrest the chief in November 1817 but a battle arose and it became an opening engagement of the First Seminole War.[5]

Anger over the destruction of the fort stimulated continued resistance during the First Seminole War.[14]:235

Memory of Negro Fort fades

With white American settlement, the memory of Fort Blount as the Negro Fort faded, from some combination of cultural discontinuity, with the Indian, free black, Maroon, Spanish, and British population displaced by incomers, and discomfort with the idea of free blacks and runaways as a serious military threat. Modern maps rarely mention Negro Fort; the site until 2016 was called Fort Gadsden Historic Site, but Fort Gadsden had a less dramatic history. None of the four historic markers at the site mentions Negro Fort. (It is mentioned on the information kiosk at the site.) The Union Jack (British flag) flies over the site; the Colonial Marines, at least, felt they were British subjects. (See Treaty of Nicolls' Outpost.) Markers call it "British post", and nothing is mentioned as to the ethnicity of the fortress's defendants, except that, as blacks and "Indians", they were not "Americans". The concern is the impression their broken bodies made on the victors:

British Fort Magazine

It is hard to imagine the horrible scene that greeted the first Americans to stand here on the morning of July 27, 1816. The remains of the 270 persons killed in the magazine explosion lay scattered about. They also found an arsenal of ten cannons, 2,500 muskets and over 150 barrels of black powder. Some original timbers from the octagonal magazine were uncovered here by excavations.

See also

References

- ↑ Carlisle, Rodney P.; Carlisle, Loretta (2012). Forts of Florida. A Guidebook. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813040127.

- ↑ "Fort Negro [sic] (Fort Gadsden)". 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, Gene Allen (2013). The Slaves' Gamble. Choosing Sides in the War of 1812. Palgrave MacMillen. ISBN 9780230342088.

- ↑ Boyd, Mark F. (October 1937). "Events at Prospect Bluff on the Appalachicola River, 1808-1818". Florida Historical Quarterly. 16 (2): 79–80.

- 1 2 3 4 "AfricanHeritage.com". africanheritage.com.

- ↑ Casualties: U. S. Navy and Marine Corps Personnel Killed and Wounded in Wars, Conflicts, Terrorist Acts, and Other Hostile Incidents Archived June 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Naval Historical Center, United States Navy.

- 1 2 3 Cox, Dale (2014). "Attack on the Fort at Prospect Bluff". exloresouthernhistory.com. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ↑ Cox, Dale (2018). "The Fort at Prospect Bluff (July 11, 1816)". exploresouthernhistory.com. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- 1 2 Federal Writers' Project (1939), Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 489

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - 1 2 Saunt, Claudio (1999). A New Order of Things. Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521660432.

- ↑ Mahon, 23.

- ↑ Mahon, 24.

- ↑ Mahon, 23-24.

- 1 2 3 Millett, Nathaniel (2013). The Maroons of Prospect Bluff and Their Quest for Freedom in the Atlantic World. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813044545.

- ↑ National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, British Fort, Aboard the Underground Railroad, retrieved December 22, 2017

External links

- USDA Forest Service (2011). Historic Fort Gadsden. The Archeology Channel. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- "North America's Largest Act of Slave Resistance", a 2015 lecture by Nathaniel Millett