LGBT rights in Cyprus

| LGBT rights in Cyprus | |

|---|---|

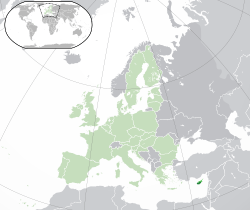

Location of Cyprus (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status |

Legal since 1998, age of consent equalised in 2002 |

| Gender identity/expression | – |

| Military service | Banned. Cyprus has an explicit ban on LGBT people serving in the military[1] |

| Discrimination protections | Sexual orientation and gender identity protections (see below) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Civil unions since 2015 |

| Adoption | Single LGBT persons are allowed to adopt. No adoption for same-sex couples. |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Cyprus may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal in Cyprus and civil unions have been legal since December 2015.

Traditionally, the socially conservative Greek Orthodox Church has had significant influence over public opinion and politics when it comes to LGBT rights. However, ever since Cyprus sought membership in the European Union, it has had to change its human rights legislation, including its laws regarding sexual orientation and gender identity. Attitudes towards members of the LGBT community are also evolving and becoming increasingly more accepting and tolerant.

Law regarding same-sex sexual activity

Although administered by the British Empire from 1878, Cyprus remained officially part of the Ottoman Empire until 1914, when it was annexed by the British Empire following the decision of the Ottoman Turks to side with Germany in the First World War. Even then, Cyprus was not officially claimed by the British Empire until 1925, following recognition of British ownership of the island by the newly created Republic of Turkey through the Treaty of Lausanne, signed by Britain and Turkey in 1923.[2] Up until this time, Ottoman laws were technically in force on the island, albeit administered by local and British colonial officials, and in respect to homosexuality, Ottoman Turkish law had been liberalised in 1858, when it had ceased to be a criminal offence throughout the Ottoman Empire.[3]

Although Britain assumed full legal ownership of Cyprus in 1925, Ottoman law was not formally replaced on the island until 1929, when Ottoman legal tolerance of homosexuality was finally ended, with the incorporation of the British Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 into Cyprus Law. For the first time since 1858, this made male homosexuality a criminal act in Cyprus. Female homosexuality was not recognised or mentioned in the law.

With independence from Britain in 1960, Cyprus retained British colonial law on the island almost in its entirety, with the relevant parts of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 becoming articles 171 to 174 of Chapter 154 of the Cypriot Criminal Code.[4] The articles were first challenged in 1993, when Alexandros Modinos, a Cypriot architect and gay rights activist won a legal court case against the Government of Cyprus, known as Modinos v. Cyprus, at the European Court of Human Rights. The Court ruled that Section 171 of the Criminal Code of Cyprus violated Modinos's right to a private life, protected under the European Convention on Human Rights, an international agreement ratified by Cyprus in 1962.

Despite the legal ruling, Cyprus did not formally revise its Criminal Code to comply with the ruling until 1998, when failing to do so meant losing membership in the European Union. Even then, the age of consent for homosexual conduct was set at eighteen, while that for heterosexual conduct was at sixteen. Aside from the unequal age of consent, the revised Criminal Code also made it a crime to "promote" homosexuality, which was used to restrict the LGBT rights movement.

In 2000, the discriminatory ban on "promoting" homosexuality was lifted, and the age of consent was equalised in 2002. Today, the universal of consent is seventeen years of age.[5] Sexual conduct that occurs in public, or with a minor, is subject to a prison term of five years.

The Cyprus military still bars homosexuals from serving, believing that homosexuality is a mental illness. Gay sexual conduct is also, technically, still a crime under military law; the term is 6 months in a military jail although this is rarely, if ever, enforced.[1]

In Northern Cyprus, Turkish Cypriot deputies passed an amendment on 27 January 2014, repealing a colonial-era law that punished homosexual acts with up to five years. It was the last territory in Europe to decriminalise sexual relations between consenting adult men. In response to the vote, Paulo Corte-Real from the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, a rights advocacy group, said that "We welcome today's vote and can finally call Europe a continent completely free from laws criminalising homosexuality".[6]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

The current law of Cyprus only recognises marriage as a union between one man and one woman. There is no official recognition of same-sex marriages. Since 2015, same-sex couples have been able to have their relationships recognised through civil unions.

On 26 November 2015, a civil unions bill was passed by the Parliament with 39 in favour, 12 against and 3 abstentions. The law was published on 9 December 2015, and took effect upon publication.[7][8][9]

Discrimination protections

Since 2004, Cyprus has implemented an anti-discrimination law (the Equal Treatment in Employment and Occupation Law 2004) that explicitly forbids discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in employment. The law was designed to comply with the European Union's Employment Framework Directive of 2000.[10]

In 2013, the Penal Code was amended to include sexual orientation and gender identity, thus criminalising all discrimination against them. In Northern Cyprus, discrimination protections were brought in by a law change on 27 January 2014.[11][12]

In May 2015, Parliament amended the Penal Code, making it a crime to engage in unacceptable behaviour towards LGBT people and commit acts of violence against people based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.[13]

Gender identity and expression

In November 2017, President Nicos Anastasiades met LGBT advocacy group Accept-LGBT Cyprus to discuss issues concerning transgender rights. A bill to allow transgender people to change their legal sex is currently being drafted, with the support of the President and the Justice Minister.[14]

Living conditions

In 1996, a criminal trial against Father Pancratios Meraklis, who was accused of sodomy, caused serious rioting that stopped the proceedings. Meraklis had been regarded as a possible bishop, but was blocked by then Archbishop of Cyprus, Chrysostomos I of Cyprus, who believed Meraklis to be homosexual and that AIDS could be spread through casual conduct.[15] These comments irked public health officials and more open-minded Cyprus citizens.

In 2003, a twenty-eight-year-old Cypriot man was barred from getting a driver's license because he was regarded as "psychologically unstable." The man had been discharged from the military for homosexuality, which the military classifies as a mental illness.[16]

The "gay scene" continues to grow in Cyprus. Bars and clubs are found in 4 cities, including Different, and gay-friendly Kaliwas Lounge in Paphos; Alaloum, Escape, and Jackare in Limassol; SecretsFreedomClub and Vinci gaysauna in Larnaca and gay-friendly establishments such as Novecento, Ithaki and Svoura in Nicosia.

HIV/AIDS

The pandemic first came to Cyprus in 1986, and since then a few hundred people have been living with HIV/AIDS.

The Government regularly tests pregnant women, drug users, National Guard troops and blood donors.[17] In a 2001 report to the United Nations, the Government broadly mentioned various efforts it had undertaken to fight the disease.[18] All non-EU foreigners seeking work and living permit on the island need to take tests for HIV, Hepatitis B & C, Syphilis and Tuberculosis; and if result is positive the permit will not be granted.

LGBT rights movement in Cyprus

In 1987–88, the Cypriot Gay Liberation Movement (AKOK, or Apeleftherotiko Kinima Omofilofilon Kiprou) was created. As the first LGBT rights organisation in the nation, it has been successful in helping to repeal the civilian criminal prohibitions regarding homosexuality.

In 2007, Initiative Against Homophobia was established in Northern Cyprus to deal with the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. On 25 April 2008, the group presented a proposal regarding the revising of criminal law to the head of Parliament, Fatma Ekenoglu.[19] In 2010, representatives of ILGA-Europe presented the proposal to the new head of Parliament, Hasan Bozer. However, no action was taken on the proposal and people continued to be arrested under claims of "unnatural sex". During the well known Sarris court case in October 2011, the Communal Democracy Party (TDP) presented the same proposal to the Parliament with the demand of urgently decriminalising homosexuality in Northern Cyprus. Since March 2012, Initiative Against Homophobia has continued its activities with the name Queer Cyprus Association.

Accept-LGBT Cyprus is the only officially registered organisation in Cyprus dealing with LGBT rights. It fully registered on 8 September 2011. It has the support of many citizens, assisted by various NGOs, the European Parliament and foreign embassies operating in Cyprus. The organisation has also had at times assistance from local municipalities and often had events held under the auspices of local city mayors.[20]

Accept-LGBT Cyprus organised the first ever Cyprus Pride parade on the island on 31 May 2014. The parade was successful with over 4,500 marching or attending the day's events. The group had expected several hundred participants, but were overwhelmed by the event's popularity. The march received extensive political support from almost all parties across the political spectrum, as well as support from former President of Cyprus George Vasiliou, the European Parliament's Office in Cyprus, the European Commission’s Representation in Cyprus and 15 embassies who marched with the parade including ambassadors and embassy staff (Austria, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States). Furthermore, for the first time ever, the embassies of Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United States hoisted a rainbow flag. Cypriot-born, international pop singer Anna Vissi also attended the march. The 81-year-old Alecos Modinos, who won a 1993 European Court of Human Rights case against Cyprus for its laws criminalising homosexuality, headed the procession. Scuffles broke out between a group of Orthodox Christian protesters including clerics who denounced the event they called "shameful", demonstrating outside the Parliament.

During a press release, Accept-LGBT Cyprus President Costa Gavrielides expressed his surprise and joy at the turnout, but also his annoyance with the civil unions bill not being submitted to Parliament, despite news of a possible April vote.[21] The bill finally passed in November 2015.

The event was preceded by the Cyprus Pride Festival, which took place between 17 May 2014 (International Day Against Homophobia) and 31 May 2014. The first day of the event a Rainbow Walk took place to the north of Nicosia with the collaboration of Accept-LGBT Cyprus and the Turkish Cypriot organisation Queer Cyprus Association, amongst others.

In Northern Cyprus, in 2008, Shortbus Movement, consisting of human rights activists, was founded. It takes action to support LGBT rights in Northern Cyprus. The group secured financial support from the European Commission Office in Cyprus and the European Parliament. It has also organised many activities to empower and mobilise members of LGBT community, by increasing awareness through sharing related information, providing informational, educational, psychological and legal services to the LGBTI community and organising and/or supporting LGBTI, gender equality and human rights thematic cultural events.

Other LGBT events and activities, providing awareness of LGBT people, have been held in Paphos and Geroskipou.[22]

Public opinion

Most Cyprus citizens are members of the Orthodox Church of Cyprus, which opposes LGBT rights. In 2000, a Major Holy Synod had to be convened to investigate rumours that Bishop Athansassios of Limassol had engaged in a homosexual relationship while a novice monk. The charges were eventually dropped.[23]

A 2006 survey showed that 75% of Cypriots disapproved of homosexuality, and many thought that it can be "cured".[24] A 2006 E.U. poll revealed that only 14% of Cypriots were in favour of same-sex marriage, with 10% also in favour of adoption.[25]

However, the situation has seen a rapid turnaround in just a few years, with a 2014 survey finding that 53.3% of Cypriot citizens thinking that civil unions should be made legal.[26]

The 2015 Eurobarometer found that 37% of Cypriots thought that same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe, 56% were against.[27]

Human rights reports

2017 United States Department of State report

In 2017, the United States Department of State reported the following, concerning the status of LGBT rights in Cyprus:

- Freedom of Expression, Including for the Press

"Freedom of Expression: The law criminalizes incitement to hatred and violence based on race, color, religion, genealogical origin, national or ethnic origin, or sexual orientation. Such acts are punishable by up to five years’ imprisonment, a fine of up to 10,000 euros ($12,000), or both. In 2015 police examined 11 complaints of verbal assault and/or hate speech based on ethnic origin, religion, sexual orientation, and color. Authorities opened criminal prosecutions in five cases that are currently pending trial."[28]

- Acts of Violence, Discrimination, and Other Abuses Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

"Antidiscrimination laws exist and prohibit direct or indirect discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Antidiscrimination laws cover employment and the following activities in the public and private domain: social protection, social insurance, social benefits, health care, education, participation in unions and professional organizations, and access to goods and services. An LGBTI NGO noted in February that equality and antidiscrimination legislation remained fragmented and failed to adequately address discrimination against LGBTI persons. NGOs dealing with LGBTI matters claimed that housing benefits favored “traditional” families. Hate crime laws criminalize incitement to hatred or violence based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

Despite legal protections, LGBTI individuals faced significant societal discrimination. As a result, many LGBTI persons were not open about their sexual orientation or gender identity, nor did they report homophobic violence or discrimination. There were reports of employment discrimination against LGBTI applicants (see section 7.d.)."[28]

- Discrimination with Respect to Employment and Occupation

"Laws and regulations prohibit direct or indirect discrimination with respect to employment or occupation on the basis of race, national origin or citizenship, sex, religion, political opinion, gender, age, disability, and sexual orientation. The government did not effectively enforce these laws or regulations. Discrimination in employment and occupation occurred with respect to race, gender, disability, sexual orientation, and HIV-positive status. Penalties provided by the law were sufficient to deter violations.

A survey published in the International Journal of Manpower in 2014 suggested that LGBTI job applicants faced significant bias compared with heterosexual applicants. The survey found that gay male applicants, who made their sexual orientation clear on their job application, were 39 percent less likely to get a job interview than equivalent male applicants who did not identify themselves as gay. Employers were 42.7 percent less likely to grant a job interview to openly lesbian applicants than to equivalent heterosexual female applicants."[28]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment only | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples (e.g. civil unions.) | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| LGBT people allowed to serve in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Conversion therapy banned on minors | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

See also

References

- 1 2 Helena Smith (26 January 2002). "Cyprus divided over gay rights". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Xypolia, Ilia (2011). "'Cypriot Muslims among Ottomans, Turks and British" (PDF). Bogazici Journal. 25 (2): 109–120. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Ishtiaq Hussain, The Tanzimat: Secular reforms in the Ottoman Empire (London: Faith Matters, 2011 p.10 URL link

- ↑ Robert T. Francoeur and Raymond J. Noonan (eds.), The Continuum Complete International Encyclopedia of Sexuality (London: Continuum, 2003) 294

- ↑ "Cyprus". ageofconsent.com. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Afanasieva, Dasha (2014-01-27). "Northern Cyprus becomes last European territory to decriminalize gay sex". Uk.reuters.com. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ↑ ΕΠΙΣΗΜΗ ΕΦΗΜΕΡΙΔΑ ΤΗΣ ΚΥΠΡΙΑΚΗΣ ΔΗΜΟΚΡΑΤΙΑΣ ΠΑΡΑΡΤΗΜΑ ΠΡΩΤΟ ΝΟΜΟΘΕΣΙΑ - ΜΕΡΟΣ Ι Αριθμός 4543 Τετάρτη ,9 Δεκεμβρίου 2015: Αριθμός 184(Ι) του 2015 ΝΟΜΟΣ ΠΟΥ ΠΡΟΝΟΕΙ ΓΙΑ ΤΗ ΣΥΝΑΨΗ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΗΣ ΣΥΜΒΙΩΣΗΣ, pp. 14-32

- ↑ Τέθηκε σε ισχύ η πολιτική συμβίωση στην Κύπρο

- 1 2 "Civil unions become law - Cyprus". InCyprus. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ↑ Implementation of Anti-discrimination directives into national law, European Union

- ↑ Owen Bowcott (2014-01-27). "Northern Cyprus votes to legalise gay sex". theguardian.com. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ↑ "Cyprus: Penal code amended to protect against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity". PinkNews. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ↑ House votes to criminalise homophobia

- ↑ President meets Accept LGBT, Cyprus Mail, 30 November 2017

- ↑ planetout.com – Meraklis Admits AIDS, Not Gay Archived 13 November 2003 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ queerday.com – Gay Cyprus man can't get driver's license Archived 10 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ cyprus-mail.com – HIV/AIDS incidence low in Cyprus Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ User (27 June 2001). "United Nations". United Nations. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Initiative Against Homophobia. "Proposal of Criminal law presented by Initiative Against Homophobia". www.queercy.org. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ Towards Inclusion: Healthcare, Education and the LGBT Community

- ↑ "Greek Cypriots in first gay pride parade". GMA Network. 2014-01-06.

- ↑ Support for LGBT community in Paphos growing, Cyprus Mail, 23 March 2018

- ↑ Cyprus synod seeks end to scandal over 'gay' bishop The Telegraph, 15 November 2000

- ↑ Overview on being gay in Cyprus Gay Cyprus Online

- ↑ Eight EU Countries Back Same-Sex Marriage Angus Reid Global Monitor

- ↑ Storm of protest over Archbishop’s anti-gay comments

- ↑ Special Eurobarometer 437 Archived 17 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 CYPRUS 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT

- ↑ Jean Callaghan and Franz Kernic, Armed Forces and International Security: Global Trends and Issues (, 2003 p.218 URL link