LGBT rights in Germany

| LGBT rights in Germany | |

|---|---|

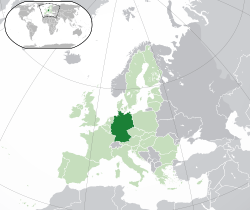

Location of Germany (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status |

Legal since 1968 (East Germany) and 1969 (West Germany) Age of consent equalised and full legalisation in 1994 |

| Gender identity/expression | Transgender persons allowed to change legal gender without required sterilisation and surgery[1] |

| Military service | LGBT people allowed to serve |

| Discrimination protections | Sexual orientation and gender identity protection nationwide; some protections vary by region (see below) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Same-sex marriage since 2017 |

| Adoption | Full adoption rights since 2017 |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights in Germany have evolved significantly over the course of the last decades. During the 1920s and early 1930s, LGBT people in Berlin were generally tolerated by society and many bars and clubs specifically pertaining to gay men were opened.[2] Although same-sex sexual activity between men was already made illegal under Paragraph 175 by the German Empire in 1871, Nazi Germany extended these laws during World War II, which resulted in the persecution and deaths of thousands of homosexual citizens. The Nazi extensions were repealed in 1950 and same-sex sexual activity between men was decriminalised in both East and West Germany in 1968 and 1969, respectively. The age of consent was equalized in unified Germany in 1994.

Same-sex marriage has been legal since 1 October 2017, after the Bundestag passed legislation giving same-sex couples full marital and adoption rights on 30 June 2017.[3] Prior to that, registered partnerships were available to same-sex couples, having been legalised in 2001. These partnerships provided most though not all of the same rights as marriages, and they ceased to be available after the introduction of same-sex marriage. Same-sex stepchild adoption first became legal in 2005 and was expanded in 2013 to allow someone in a same-sex relationship to adopt a child already adopted by their partner.[4] Discrimination protections on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity vary across Germany, but discrimination in employment and the provision of goods and services is banned countrywide. Transgender people have been allowed to change their legal gender since 1980. The law initially required them to undergo surgical alteration of their genitals in order to have key identity documents changed. This has since been declared unconstitutional.[5]

Despite two of the three main political parties in the German Government being socially conservative on the issues of LGBT rights, Germany has frequently been seen as one of the most gay friendly countries in the world.[6][7] Recent polls have indicated that a large majority of Germans support same-sex marriage.[8][9] Another poll in 2013 indicated that 87% of Germans believed that homosexuality should be accepted by society, which was the second highest score in the world (only 39 countries were polled) following Spain (88%).[10] Berlin has been referred to by publications as one of the most gay friendly cities in the world.[11] The former Mayor of Berlin, Klaus Wowereit, is one of the most famous openly gay men in Germany, next to the former Mayor of Hamburg, Ole von Beust, the Federal Minister of Health, Jens Spahn, the deceased former Minister for Foreign Affairs, Guido Westerwelle, the former Federal Ministry of the Environment Barbara Hendricks and comedians Hape Kerkeling, Hella von Sinnen and Lutz van der Horst. Founded in 1981, the Akademie Waldschlösschen, an adult education conference center near Göttingen, has developed into a national networking hub for LGBTI teachers, lawyers, clergy, gay fathers and gay and lesbian student groups at German universities, many in cooperation with TransAktiv and Intersexuelle Menschen e.V..

History of laws regarding same-sex sexual activity

Homosexuality was punishable by death in the Holy Roman Empire from 1532 until its dissolution and in Prussia from 1620 to 1794. The influence of the Napoleonic Code in the early 1800s sparked decriminalisations in much of Germany outside of Prussia. However, in 1871, the year the federal German Empire was formed, Paragraph 175 of the new Penal Code recriminalised homosexual acts. The law was extended under Nazi rule, and convictions multiplied by a factor of ten to about 8,000 per year. Penalties were severe, and 5,000–15,000 suspected offenders were interned in concentration camps, where most of them died.

The Nazi additions were repealed in East Germany in 1950, but homosexual relations between men remained a crime until 1968. West Germany kept the more repressive version of the law, legalising male homosexual activity one year after East Germany, in 1969. The age of consent was equalized in East Germany through a 1987 court ruling, with West Germany following suit in 1989; it is now 14 years (16/18 in some circumstances) for female-female, male-male and female-male activity.

Progression in East Germany (1949–1990)

East Germany inherited Paragraph 175. Communist gay activist Rudolf Klimmer, modelling himself on Magnus Hirschfeld and his Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, campaigned in 1954 to have the law repealed, but was unsuccessful. His tireless work did prevent any further convictions for homosexuality after 1957.[12]

In the five years following the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, the GDR Government instituted a program of "moral reform" to build a solid foundation for the new socialist republic, in which masculinity and the traditional family were championed, while homosexuality, seen to contravene "healthy mores of the working people", continued to be prosecuted under Paragraph 175. Same sex activity was "alternatively viewed as a remnant of bourgeois decadence, a sign of moral weakness, and a threat to the social and political health of the nation".[13]

In East Germany, Paragraph 175 ceased to be enforced from 1957 but remained on the books until 1968. Officially, homosexuality was decriminalised in East Germany in 1968.[12][14]

According to historian Heidi Minning, attempts by lesbians and gay activists in East Germany to establish a visible community were "thwarted at every turn by the GDR Government and the SED party".

Minning wrote: Police force was used on numerous occasions to break up or prevent public gay and lesbian events. Centralised censorship prevented the presentation of homosexuality in print and electronic media, as well as the import of such materials.[15]

The Protestant Church provided more support than the state, allowing meeting spaces and printing facilities.[16]

Towards the end of the 1980s, just before the collapse of the iron curtain, the East German Government opened a state-owned gay disco in Berlin.[17] On 11 August 1987, the East German Supreme Court affirmed that "homosexuality, just like heterosexuality, represents a variant of sexual behavior. Homosexual people do therefore not stand outside socialist society, and the civil rights are warranted to them exactly as to all other citizens".[13]

In 1988, the German Hygiene Museum in Dresden commissioned the state-owned film studio, DEFA, to make the documentary film Die andere Liebe (The Other Love). It was the first DEFA film about homosexuality and its aim was to convey official state acceptance.[18] In 1989, the German Hygiene Museum also commissioned DEFA to make the GDR's only HIV/AIDS prevention documentary, Liebe ohne Angst (Love Without Fear). This did not focus on homosexuality directly but pointed out that AIDS was not a "gay disease".[19][20]

The 1989 DEFA produced film Coming Out, directed by Heiner Carow, tells the story of an East German man coming to accept his homosexuality, with much of it shot in East Berlin gay bars. It was the only East German feature film on the theme of same-sex desire ever produced.[21] It won a number of awards including a Silver Bear and Teddy Award at 40th Berlin International Film Festival, and awards at the National Feature Film Festival of the GDR.[21][22][23]

Jürgen Lemke is considered one of the most prominent East German gay rights activists and has published a book on the subject (Gay Voices from East Germany, English edition published in 1991). Lemke claimed that the gay community was far more united in the GDR than it was in the West.[24]

West Germany (1949–1990)

West Germany inherited Paragraph 175, which remained on the books until 1969. However, as opposed to East Germany, the churches' influence in West Germany was very strong. Fundamentalist Protestants and the Roman Catholic Church were staunchly opposed to LGBT rights legislation.[25]

As a result of these strong socially conservative influences, the German Christian Democratic Union, the dominant political force in post-war West Germany, tended to ignore or oppose most gay rights issues. While their frequent coalition partners, the Free Democratic Party tended to have a stronger belief in civil liberties, they were, as a smaller party, less likely to alienate the more socially conservative elements in the larger Christian Democratic Union.[25]

During the Cold War era, support for gay rights in Germany was generally restricted to the Free Democratic Party, the Social Democratic Party and, later in the 1980s, the Green Party. At the national level, advancements in gay rights did not begin to happen until the end of the Cold War and the electoral success of the Social Democratic Party. For example, in 1990, the law was changed so that homosexuality and bisexuality were no longer grounds for being discriminated against in the military.[25]

In 1986, the popular soap opera Lindenstraße showed the first gay kiss on German TV. From then on, many other television shows followed this example. Especially the creation of private TV stations in 1984 resulted in a stronger same-sex presence in the media by the end of the decade. The station RTL in particular was very gay-friendly and some TV stars had come out by then.[25]

Annulment of convictions

In 2002, the German Government decided to overturn any convictions for homosexuality made during the Nazi period.[26]

In May 2016, Justice Minister Heiko Maas announced that gay and bisexual men who were convicted of same-sex sexual activity after World War II would have their convictions overturned.[26] Mr Maas said the following in a statement:

We will never be able to eliminate completely these outrages by the state, but we want to rehabilitate the victims. The homosexual men who were convicted should no longer have to live with the taint of conviction.

In October 2016, the German Government announced the introduction of a draft law to pardon around 50,000 men for the prosecutions they endured due to their sexual orientation.[27] On 22 March 2017, the Germany Cabinet officially approved the bill.[28] The bill, which also foresees compensation of €3,000 (£2,600) for each conviction, plus €1,500 (£1,300) for every year of jail time, then had to obtain parliamentary approval.[29] On 22 June 2017, the Bundestag (German Parliament) unanimously passed the bill to implement the scheme to rehabilitate gay and bisexual men.[30] The bill then went back to the Bundesrat for final approval, and was signed into law by the President on 17 July 2017.[31]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

Same-sex couples have been legally recognized in Germany since 2001. That year, registered life partnerships (effectively, a form of civil union) were instituted, giving same-sex couples rights and obligations in areas such as inheritance, alimony, health insurance, immigration, hospital and jail visitations, and name change. Subsequently, the Constitutional Court repeatedly ruled in favor of same-sex couples in registered partnerships, requiring the Bundestag to make incremental changes to the partnership law. In one case, the European Court of Justice ruled that refusing a widow's pension to the same-sex partner of a deceased person is direct discrimination if the partnership was comparable to marriage (see same-sex unions in the European Union).[32]

Even though a majority of the political parties in the Bundestag supported legalising same-sex marriage, attempts to follow through with the proposal were repeatedly blocked by CDU/CSU, the largest parliamentary party and the dominant party in the government coalitions since 2005. This changed on the final sitting day of the Bundestag before the 2017 summer break, when the junior party in the coalition, the Social Democratic Party, brought on a bill to legalise same-sex marriage and adoption which had previously passed the Bundesrat in September 2015.[33] German Chancellor Merkel moderated her stance on the issue by allowing members of the CDU/CSU to follow their personal conscience rather than the party line, which freed up moderate members who have long been in favour of same-sex marriage to vote for it.[34] On 30 June 2017,[35] the SPD, Die Linke and the Greens as well as 75 moderate members of the CDU/CSU formed a majority in the Bundestag to pass the bill by 393 votes to 226.[36] The law came into effect three months after promulgation, on 1 October 2017.[37]

The first same-sex weddings in Germany were celebrated on 1 October 2017.[38] Berlin couple Karl Kreile and Bodo Mende, a couple for 38 years,[39] were the first same-sex couple to exchange their vows under the new law and did so at the town hall of Schöneberg, Berlin.[39]

Adoption and parenting

In 2004, the registered partnership law (originally passed in 2001) was amended, effective on 1 January 2005, to give registered same-sex couples limited adoption rights (stepchild adoption only) and reform previously cumbersome dissolution procedures with regard to division of property and alimony. In 2013, the Supreme Constitutional Court ruled that if one partner in a same-sex relationship has adopted a child, the other partner has the right to become the adoptive mother or father of that child as well; this is known as "successive adoption".[40] The same-sex marriage law, passed in June 2017, gave same-sex couples full adoption rights.[41][37] On 10 October 2017, a court in Berlin's Kreuzberg district approved the first application for joint adoption of a child by a same-sex couple.[42]

There is no legal right to assisted reproduction procedures for lesbian couples, such as artificial insemination and in vitro fertilisation, but such practices are not explicitly banned either. The German Medical Association is against explicit legalisation and directs its members not to perform such procedures. Since this directive is not legally binding, however, sperm banks and doctors may work with lesbian clients if they wish. This makes it harder for German lesbian couples to have children than in some other countries, but it is becoming increasingly popular. In addition, lesbian parents are not both automatically recognized on their child(ren)'s birth certificates, as one of the partners has to adopt the child(ren) of the other partner, whether biological or adopted. A bill initiated by Alliance 90/The Greens in June 2018 to rectify this inequality is pending in the Bundestag.[43][44][45]

Military service

LGBT people are not banned from military service.

The Bundeswehr maintained a "glass ceiling" policy that effectively banned homosexuals from becoming officers until 2000. First Lieutenant Winfried Stecher, an army officer demoted for his homosexuality, had filed a lawsuit against former Defense Minister Rudolf Scharping. Scharping vowed to fight the claim in court, claiming that homosexuality "raises serious doubts about suitability and excludes employment in all functions pertaining to leadership". However, before the case went to trial, the Defense Ministry reversed the policy. While the German Government declined to issue an official explanation for the reversal, it was widely believed that Scharping was overruled by former Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and former Vice-Chancellor Joschka Fischer. Nowadays, according to general military orders given in the year 2000, tolerance towards all sexual orientations is considered to be part of the duty of military personnel. Sexual relationships and acts amongst soldiers outside service times, regardless of the sexual orientation, are defined to be "irrelevant", regardless of the rank and function of the soldier(s) involved, while harassment or the abuse of functions is considered a transgression, as well as the performance of sexual acts in active service.[46] Transgender persons may also serve openly in the German Armed Forces.[47]

Discrimination protections

In the fields of employment, goods and services, education and health services, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity is illegal throughout Germany.

Some state constitutions have anti-discrimination laws that include sexual orientation and gender identity, including the constitutions of Berlin (since 1995), Brandenburg (since 1992), Bremen (since 2001), Saarland (since 2011) and Thuringia (since 1993), and Saxony-Anhalt in the public sector since 1997.[48][49][50]

As a signatory to the Treaty of Amsterdam, Germany was required to amend its national anti-discrimination laws to include, among others, sexual orientation. It failed to do so for six years, due to discussions about the scope of the proposed laws. Some of the proposals were debated because they actually surpassed the requirements of the Treaty of Amsterdam (namely, extending discrimination protection for all grounds of discrimination to the provision of goods and services); the final version of the law, however, has been criticised as not fully complying with some parts of the Treaty, especially with respect to the specifications about the termination of work contracts through labor courts. The Bundestag finally passed the Equal Treatment Act on 29 June 2006; the Bundesrat voted on it without discussion on 7 July 2006. Having come into force on 18 August 2006, the law bans discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics in employment, education, health services and the provision of goods and services.[51]

Hate speeches on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity are banned in Germany.[52] German law prohibits incitement to hatred based on membership to a certain social or ethnic group.

Positions of political parties

The conservative parties Alternative for Germany (AfD), Christian Democratic Union and Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) are mostly opposed to full LGBT rights, yet support most basic rights such as civil unions. All other major parties, the Social Democratic Party (SPD), The Left, Alliance '90/The Greens and the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) support LGBT rights, including same-sex marriage.

However, CDU/CSU has been the senior coalition party in government since 2005. During the past coalitions with the SPD (2005-2009, 2013-present) and the FDP (2009-2013), the CDU/CSU generally blocked advances proposed by the other parties.

Gender identity and expression

Since 1980, the Gesetz über die Änderung der Vornamen und die Feststellung der Geschlechtszugehörigkeit in besonderen Fällen has stated that transgender persons may change their legal sex following sex reassignment surgery and sterilization.[48][53] In January 2011, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that these two requirements were unconstitutional.[54][5]

Intersex rights

Since 2013, German law has allowed children born with atypical sexual anatomy to have their gender left blank instead of being categorised as male or female. The Swiss activist group Zwischengeschlecht criticised this law, arguing that "if a child’s anatomy does not, in the view of physicians, conform to the category of male or the category of female, there is no option but to withhold the male or female labels given to all other children".[55] The German Ethics Council and the Swiss National Advisory Commission also criticised the law, saying that "instead of individuals deciding for themselves at maturity, decisions concerning sex assignment are made in infancy by physicians and parents".[56]

In November 2017, the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) ruled that civil status law must allow a third gender option.[57] This means that intersex people will have another option besides being listed as female or male or having a blank gender entry.[58] The Government presented its proposal on the matter in August 2018.[59] Intersex individuals will be able to register themselves as "divers" on official documents.[60]

Conversion therapy

Conversion therapy has a negative effect on the lives of LGBT people, and can lead to low self-esteem, depression and suicide ideation. It is opposed by every medical organisation in Germany.[61]

In 2008, the German Government declared itself completely opposed to the pseudoscientific practice.[62] A petition to call on the Health Ministry to ban it was launched in July 2018, and had collected about 60,000 signatures by mid-August 2018.

Blood donation

Bone marrow donation has been allowed since December 2014.[63]

In June 2016, German health ministers announced that the ban on gay and bisexual men donating blood would be lifted, replacing it with a one-year deferral period. The proposal to lift the ban was championed by Monika Bachmann, Saarland's Health Minister.[64]

Since summer 2017, gay and bisexual men have been allowed to donate blood, provided they haven't had sex for twelve months.[65]

Openly gay and lesbian politicians

There are several prominent German politicians who are openly gay. Among them are Berlin's former Mayor Klaus Wowereit (having outed himself with the famous words "Ich bin schwul – und das ist auch gut so!" [English: "I am gay – and that's a good thing!"]) and Johannes Kahrs (from the SPD); Volker Beck, Kai Gehring, Ulle Schauws, Gerhard Schick, Anja Hajduk (from the Green Party); Harald Petzold (The Left); Jens Spahn, Stefan Kaufmann (from the CDU); Bernd Fabritius (from the CSU); Michael Kauch and Guido Westerwelle, former federal Foreign Minister and former head of the liberal Free Democratic Party. In addition, Hamburg's former Mayor Ole von Beust (Christian Democratic Union) didn't deny anything when his father outed him but considered it a private matter; after leaving office he began talking about his homosexuality. In July 2007, Karin Wolff, then Minister of Education for Hesse, came out as a lesbian.[66] In December 2013, Barbara Hendricks (SPD), the Federal Minister for the Environment in the Third Merkel Cabinet, came out as lesbian. In 2012, Michael Ebling (SPD) became the Mayor of Mainz. In 2013 and 2015, Sven Gerich (SPD) and Thomas Kufen (CDU) became the openly gay mayors of Wiesbaden and Essen, respectively.

Public opinion

A 2013 Pew Research Center poll indicated that 87% of Germans believed that homosexuality should be accepted by society, which was the second highest in the world (only 39 countries were polled) following Spain (88%).[10]

Nevertheless, 46% of 20,000 German LGBT people said they had experienced discrimination because of their sexual orientation and gender identity in the past year per the 2013 results of a survey by EU's Fundamental Rights Agency (47% was the EU average). Two-thirds of respondents said they concealed their sexual orientation at school and in public life and a fifth felt discriminated at work.[67]

In May 2015, PlanetRomeo, an LGBT social network, published its first Gay Happiness Index (GHI). Gay men from over 120 countries were asked about how they feel about society’s view on homosexuality, how they experience the way they are treated by other people and how satisfied are they with their lives. Germany was ranked 14th with a GHI score of 68.[68]

A 2017 poll found that 83% of Germans supported same-sex marriage, 16% were against.[69] For comparison, the 2015 Eurobarometer found that 66% of Germans thought that same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe, 29% were against.[70]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws concerning gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples (e.g. unregistered cohabitation, life partnership) | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Stepchild adoption of an adopted child | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Recognition of adoption for single people regardless of sexual orientation | |

| Automatic parenthood on birth certificates for children of same-sex couples | |

| LGBT people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Third gender option | |

| Access to IVF for lesbian couples | |

| Conversion therapy banned by law | |

| Homosexuality declassified as an illness | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

(*) Some states have their own anti-discrimination laws that include sexual orientation and gender identity.

See also

References

- ↑ "Prerequisites for the statutory recognition of transsexuals according to § 8.1 nos. 3 and 4 of the Transsexuals Act are unconstitutional" (PDF).

- ↑ Ginn, H. Lucas (12 October 1995). "Gay Culture Flourished In Pre-Nazi Germany". Update, Southern California's gay and lesbian weekly newspaper. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Germany's Bundestag passes bill on same-sex marriage". Deutsche Welle. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "German court expands adoption rights of gay couples". Reuters. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- 1 2 "ERT Notes Steps Taken Around the World Recognising the Gender Identity of Gender Variant Persons". Equal Rights Trust. 14 December 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Rebecca Baird-Remba (23 March 2013). "World's Most Gay Friendly Countries". Business Insider. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "The 20 most and least gay-friendly countries in the world". GlobalPost. 26 June 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Enquête sur la droitisation des opinions publiques européennes" [Survey of the European public about changes in law] (PDF). IFOP Département Opinion et Stratégies d'Entreprise (in French). Institut français d'opinion publique. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ Same-Sex Marriage Citizens in 16 Countries Assess Their Views on Same-Sex Marriage for a Total Global Perspective Archived 14 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "The Most Gay-Friendly Country in the World is... - Spain, followed by Germany, Czech Republic, and Canada, new study finds". Newser.com. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

- ↑ Marcus Field (17 September 2008). "The ten best places in the world to be gay". The Independent. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

Berlin. It may have taken 75 years, but the German capital once again enjoys the kind of open gay scene that Christopher Isherwood described so evocatively in his 1939 memoir Goodbye to Berlin. Perhaps the painful period of Nazi rule and division makes the city even more attractive to people with alternative lifestyles - you have to be unconventional to want to live here. The magnificently restored 19th-century buildings, the grand boulevards and the famous park and woodlands make the perfect backdrop for queer culture. A former mayor of Berlin is gay, the Kit Kat club still exists, and Europe's first exclusively gay old people's home - the Asta Nielsen Haus - opened in the city this year.

- 1 2 Manfred Herzer, J. Edgar Bauer (Hrsg.): Hundert Jahre Schwulenbewegung, Verlag rosa Winkel, 1998, ISBN 3-86149-074-9, S. 55.

- 1 2 Take a look inside the burgeois terror of gay life behind the Berlin Wall

- ↑ Communist East Germany’s awful track record on homosexuality

- ↑ WHO IS THE 'I' IN "I LOVE YOU"?: THE NEGOTIATION OF GAY AND LESBIAN IDENTITIES IN FORMER EAST BERLIN, GERMANY

- ↑ Homosexuality in East Germany (retrospective account, 1994)

- ↑ James Kirchick (15 February 2013). "Documentary Explores Gay Life in East Germany". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ The Other Love (Die andere Liebe) on DEFA Library website. Retrieved 6 July 2018

- ↑ Love Without Fear (Liebe ohne Angst) on DEFA Library website. Retrieved 7 July 2018

- ↑ Liebe ohne Angst on the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum. eMuseum database. Retrieved 7 July 2018

- 1 2 Wagner, Brigitte B. (ed.) (2014) DEFA after East Germany, pp. 229-232. London: Camden House.

- ↑ Berlinale: 1990 Prize Winners. Retrieved 7 July 2018

- ↑ Teddy Award - Coming Out. Retrieved 7 July 2018

- ↑ Being Gay in Germany: An Interview with Jürgen Lemke

- 1 2 3 4 Whisnant, Clayton. Male Homosexuality in West Germany: Between Persecution and Freedom, 1945–69. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2013

- 1 2 "Germany anti-gay law: Plan to rehabilitate convicted men". BBC News. 13 May 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Meka Beresford (8 October 2016). "Germany to pay out 30 million euros in compensation to men convicted under historic gay sex laws". Pink News. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Germany to quash 50,000 gay convictions". 22 March 2017 – via www.bbc.com.

- ↑ Lizzie Dearden (22 March 2017). "Germany to officially pardon 50,000 gay men convicted under Nazi-era law". Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Germany to quash convictions of 50,000 gay men under Nazi-era law". The Guardian. AFP. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Consensual Homosexual Acts (Criminal Rehabilitation) Act

- ↑ "EU backs gay man's pension rights". BBC News. 1 April 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Nick Duffy (26 September 2016). "Germany's Bundesrat passes equal marriage bill despite Merkel's opposition". Pink News. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Der Riss unterm Konfettiregen". Die Zeit. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "German Parliament Paves Way For Same-Sex Marriage". MSNBC. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Germany's Bundestag passes bill on same-sex marriage". Deutsche Welle. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- 1 2 "German president signs gay marriage bill into law". Deutsche Welle. 21 July 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Germany's first same-sex "I do"'s as marriage equality dawns". Reuters. 30 September 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- 1 2 "Germany gay marriage: Couple are first to marry under new law". BBC News. 1 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Germany strengthens gay adoption rights". Deutsche Welle. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Germany's Bundestag passes bill on same-sex marriage". Deutsche Welle. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Gay couple becomes first in Germany to adopt child". Deutsche Welle. 10 October 2017.

- 1 2 "Ein Jahr Ehe für alle". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. 1 October 2018.

- 1 2 Höhne, Valerie (27 September 2018). "Vor über einem Jahr wurde die "Ehe für alle" beschlossen. Sind nun also alle gleichgestellt? Gibt es keine Diskriminierung". Der Spiegel.

- 1 2 "Neue Familien". Queer.de. 30 September 2018.

- ↑ Cf. two orders of 2000: German Military Forces (Bundeswehr) (2000). "Anlage B 173 zu ZDv 14/3" (PDF) (in German). Working Group 'Homosexuals in the Bundeswehr'. Retrieved 8 October 2017. ; and Inspector General of the German Military Forces (Bundeswehr) (2000). "Führungshilfe für Vorgesetzte – Sexualität" (PDF) (in German). Working Group 'Homosexuals in the Bundeswehr'. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Lesley Clark (14 October 2014). "Transgender military personnel openly serving in 18 countries to convene in DC". Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Rainbow Europe". rainbow-europe.org. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Diskriminierungsverbot in die Bremische Landesverfassung" [Constitution of Bremen prohibits discrimination] (in German). Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ ""Sexuelle Identität" soll Teil der saarländischen Landesverfassung warden" ["Sexual identity" is to be part of the Saarland constitution] (in German). 25 February 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Antidiskriminierungsstelle - Publikationen - AGG in englischer Sprache". antidiskriminierungsstelle.de. 28 August 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Strafgesetzbuch: Volksverhetzung

- ↑ "TSG - Gesetz über die Änderung der Vornamen und die Feststellung der Geschlechtszugehörigkeit in besonderen Fallen" [TSG - Act on the modification of the first names and the determination of the sex affiliation in special cases]. www.gesetze-im-internet.de (in German). Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "German Constitutional Court declares compulsory surgeries unconstitutional". tgeu.org. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Ellen K. Feder (7 November 2013). "Germany Has an Official Third Gender". The Atlantic. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Intersexuality Deutscher Ethikrat Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Civil Status Law Must Allow a Third Gender Option

- ↑ Gemany officially recognising 'third sex' other than male and female The Independent, 8 November 2017

- ↑ Regierung will Option für drittes Geschlecht schaffen

- ↑ Regierung will Option für drittes Geschlecht schaffen, Die Zeit, 15 August 2018

- ↑ Gay conversion therapy gaining European followers

- ↑ (in German) Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Volker Beck (Köln), Josef Philip Winkler, Hans-Christian Ströbele, weiterer Abgeordneter under der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN

- ↑ "Häufige Fragen". www.dkms.de. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Stefanie Gerdes (30 June 2016). "Germany's health ministers demand gay blood ban be lifted". Gay Star News. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- 1 2 "Homosexuelle Männer dürfen Blut spenden - nach einem Jahr Enthaltsamkeit". Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "CDU-Ministerin liebt eine Heilpraktikerin" [CDU minister loves healer]. Bild (in German). 3 July 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ EU Study Finds Widespread Homophobia in Europe Der Spiegel May 17, 2013

- ↑ The Gay Happiness Index. The very first worldwide country ranking, based on the input of 115,000 gay men Planet Romeo. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "CSU plans family-centered campaign, as Germans warm to gay marriage". 2 April 2017. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Special Eurobarometer 437 Archived 22 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "BUNDESGERICHTSHOF BESCHLUSS vom 10. Dezember 2014 in der Personenstandssache" (PDF). Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ German Wikipedia on the Equal Treatment Act (website version as of 6 November 2006)

- ^ Jennifer V. Evans. The moral state: Men, mining, and masculinity in the early GDR, German History, 23 (2005) 3, 355–370

- ^ Heidi Minning. Who is the 'I' in "I love you"?: The negotiation of gay and lesbian identities in former East Berlin, Germany. Anthropology of East Europe Review, Volume 18, Number 2, Autumn 2000

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT in Germany. |

- Lesben- und Schwulenverband in Deutschland (LSVD) — The Lesbian and Gay Federation of Germany (in German)

- lgbti.de — LGBTI Initiative for certification and sealing (in German)

- Queer – Schwul informiert — LGBT news from Germany and around the world (in German)