LGBT rights in France

| LGBT rights in France | |

|---|---|

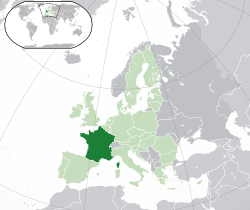

Location of Metropolitan France (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status |

Legal since 1791, age of consent (re)equalised in 1982 |

| Gender identity/expression | Transgender people allowed to change legal gender without surgery |

| Military service | LGBT people allowed to serve openly |

| Discrimination protections | Sexual orientation and gender identity protections (see below) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships |

Civil Solidarity Pact since 1999/2009 Same-sex marriage since 2013 |

| Adoption | LGBT individuals and same-sex couples allowed to adopt |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) rights in France have been seen as traditionally liberal.[1] Although same-sex sexual activity was a capital crime that often resulted in the death penalty during the Ancien Régime, all sodomy laws were repealed in 1791 during the French Revolution. However, a lesser known indecent exposure law that often targeted homosexuals was introduced in 1960 before being repealed twenty years later.

The age of consent for same-sex sexual activity was altered more than once before being equalised in 1982 under then–President of France François Mitterrand. After granting same-sex couples domestic partnership benefits known as the civil solidarity pact, France became the thirteenth country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage in 2013. Laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity were enacted in 1985 and 2012, respectively. Transgender individuals are allowed to change their legal gender and in 2009 France became the first country in the world to declassify transgenderism as a mental illness. Since 2017, transgender people have been allowed to change their legal gender without undergoing surgery or receiving any medical diagnosis.[2]

France has frequently been named one of the most gay friendly countries in the world.[2] Recent polls have indicated that a majority of the French support same-sex marriage and in 2013,[3] another poll indicated that 77% of the French population believed homosexuality should be accepted by society, one of the highest in the 39 countries polled.[4] Paris has been named by many publications as one of the most gay friendly cities in the world, with Le Marais, Quartier Pigalle and Bois de Boulogne being said to have a thriving LGBT community and nightlife.[5]

Law regarding same-sex sexual activity

Sodomy laws

Before the French Revolution, sodomy was a serious crime. Jean Diot and Bruno Lenoir were the last homosexuals burned to death on 6 July 1750.[6] The first French Revolution decriminalised homosexuality when the Penal Code of 1791 made no mention of same-sex relations in private. This policy on private sexual conduct was kept in the Penal Code of 1810, and followed in nations and French colonies that adopted the Code. Still, homosexuality and cross-dressing were widely seen as being immoral, and LGBT people were still subjected to legal harassment under various laws concerning public morality and order. Some homosexuals from the regions of Alsace and Lorraine, which were annexed by Nazi Germany in 1940, were persecuted and interned in concentration camps.

Higher age of consent

An age of consent was introduced on 28 April 1832. It was fixed to 11 years for both sexes, and later raised to 13 years in 1863. On 6 August 1942, the Vichy Government introduced a discriminative law in the Penal Code: article 334 (moved to article 331 on 8 February 1945[7] by the Provisional Government of the French Republic) increased the age of consent to 21 for homosexual relations and 15 for heterosexual ones. The age of 21 was then lowered to 18 in 1974, which had become the age of legal majority.[8] This law remained valid until 4 August 1982, when it was repealed under President François Mitterrand to equalise the age of consent at 15 years of age,[9] despite the vocal opposition of Jean Foyer in the French National Assembly.[10]

Indecent exposure

A less known discriminative law was adopted in 1960, inserting into the Penal Code (article 330, 2nd alinea) a clause that doubled the penalty for indecent exposure for homosexual activity. This ordonnance[11] was intended to repress pimping. The clause against homosexuality was adopted due to a wish of Parliament, as follows:

This ordonnance was adopted by the executive after it was authorised by Parliament to take legislative measures against national scourges such as alcoholism. Paul Mirguet, a Member of the National Assembly, felt that homosexuality was also a scourge, and thus proposed a sub-amendment, therefore known as the Mirguet amendment, tasking the Government to enact measures against homosexuality, which was adopted.[12][13]

Article 330 alinea 2 was repealed in 1980 as part of an act redefining several sexual offenses.[14]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

Civil solidarity pacts (PACS), a form of registered domestic partnership, were enacted in 1999 for both same-sex and unmarried opposite-sex couples by the Government of Lionel Jospin. Couples who enter into a PACS contract are afforded most of the legal protections, rights, and responsibilities of marriage. The right to adoption and artificial insemination are, however, denied to PACS partners (and are largely restricted to married couples). Unlike married couples, they were originally not allowed to file joint tax returns until after 3 years, though this was repealed in 2005.[15]

Civil unions/domestic partnerships conducted under laws in foreign countries are only recognised for a few countries. Registered civil partnerships in the United Kingdom are not recognised – the only solution currently available for a couple in a civil partnership to gain PACS rights in France is to dissolve their civil partnership and then establish a PACS. Registered partnerships from the Netherlands, by contrast, are already recognised. This does not, however, allow for dual citizenship, which is reserved for married couples. For example, a French citizen who enters into a registered partnership with a Dutch citizen in the Netherlands, and therefore assumes Dutch nationality, automatically loses their French citizenship.

.svg.png)

On 14 June 2011, the National Assembly of France voted 293–222 against legalising same-sex marriage.[16] Deputies of the majority party Union for a Popular Movement voted mostly against the measure, while deputies of the Socialist Party mostly voted in favor. Members of the Socialist Party stated that legalisation of same-sex marriage would become a priority should they gain a majority in the 2012 elections.[17] On 7 May 2012, François Hollande won the election. In October, a new marriage bill was introduced by the French Government.[18] On 2 February 2013, the National Assembly approved Article 1 of the bill, by 249 votes against 97.[19] On 12 February 2013, the National Assembly approved the bill as a whole in a 329–229 vote and sent it to the country's Senate.[20] The majority of the ruling Socialist Party voted in favor of the bill (only 4 of its members voted no) while the majority of the opposition party UMP voted against it (only 2 of its members voted yes).[21]

On 4 April 2013, the Senate started the debate on the bill and five days later it approved its first article in a 179–157 vote.[22] On 12 April, the Senate approved the bill with minor amendments. On 23 April, the National Assembly approved the amended bill by a vote of 331 to 225, thus extended marriage and adoption rights to same-sex couples, making France the 13th country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage.[1]

However, a challenge to the law by the conservative UMP party was filed with the Constitutional Council following the vote.[23][24] On 17 May 2013, the Council ruled that the law is constitutional.[25] On 18 May 2013, President Francois Hollande signed the bill into law,[26] which was officially published the next day in the Journal officiel.[27] The first official same-sex ceremony took place on 29 May in the city of Montpellier.[28]

Adoption and parenting

Same-sex couples have been legally able to adopt children since May 2013, when the same-sex marriage law took effect. The first joint adoption by a same-sex couple was announced on 18 October 2013.[29][30]

As of 2018, lesbian couples do not have access to assisted reproductive technology. "Procréation médicalement assistée" (PMA) is only available to heterosexual couples in France. A poll in 2012 showed that 51% of the French population supported allowing lesbian couples to access it.[31] The French Socialist Party also supports it.[32] In June 2017, a spokesperson for French President Emmanuel Macron stated that the Government intends to legislate to allow assisted reproduction for lesbian couples. This followed a report by an independent ethics panel in France which recommended that PMA law be revised to include lesbian couples and single people.[33] Marlène Schiappa, the Minister for Gender Equality, has said that a bill to allow lesbian couples and single women to access assisted reproduction will likely pass the Parliament in 2018.[34] In 2017, a poll indicated that 64% of the French people supported the extension of assisted reproduction to lesbian couples.[35] In July 2018, MP Guillaume Chiche introduced a bill to legalise assisted reproduction for lesbian couples and single women.[36][37]

On 5 July 2017, the Court of Cassation ruled that a child born to a surrogate mother abroad can be adopted by the partner of his or her biological father. However, the court refused a request that the two parents listed on the foreign birth certificate be automatically recognised.[38]

Discrimination protections

In 1985, national legislation was enacted to prohibit sexual orientation based discrimination in employment, housing and other public and private provisions of services and goods.[2] In July 2012, the French Parliament added sexual identity to the protected grounds of discrimination in French law. The phrase sexual identity was used synonymous with gender identity despite some criticism from ILGA-Europe, who nevetheless still considered it an important step.[39][40] On 18 November 2016, a new law amended article 225-1 of the French Penal Code and replaced "sexual identity" with "gender identity".[41]

Discrimination in schools

In March 2008, Xavier Darcos, Minister of Education, announced a policy fighting against all forms of discrimination, including homophobia, in schools, one of the first in the world. It was one of 15 national priorities of education for the 2008–2009 school year.

The Fédération Indépendante et Démocratique Lycéenne (FIDL) (Independent and Democratic Federation of High School Students) – the first high school student union in France – has also launched campaigns against homophobia in schools and among young people.

Hate crime laws

On 31 December 2004, the National Assembly approved an amendment to existing anti-discrimination legislation, making homophobic, sexist, racist, xenophobic etc. comments illegal. The maximum penalty of a €45,000 fine and/or 12 months imprisonment has been criticised by civil liberty groups such as Reporters Without Borders as a serious infringement on free speech. But the conservative Government of President Jacques Chirac pointed to a rise in anti-gay violence as justification for the measure. Ironically, an MP in Chirac's own UMP party, Christian Vanneste, became the first person to be convicted under the law in January 2006 although this conviction was later cancelled by the Court of Cassation after a refused appeal.[42]

The law of December 2004 created the Haute autorité de lutte contre les discriminations et pour l'égalité (High Authority against Discrimination and for Equality). Title 3 and Articles 20 and 21 of the law amended the law of 29 July 1881 on freedom of the press to make provisions for more specific offenses including injury, defamation, insult, incitement to hatred or violence, or discrimination against a person or group of persons because of their gender, sexual orientation or disability.

When a physical assault or murder is motivated by the sexual orientation of the victim, the law increases the penalties that are normally given.

Gender identity and expression

Transsexual persons are allowed to change their legal sex. In 2009, France became the first country in the world to remove transsexualism from its list of diseases.[43] Transsexualism is part of the ALD 31 and treatment is funded by Sécurité Sociale.[44]

Discrimination on the basis of gender identity (sexual identity) has been banned since 2012.[39][40] In 2016, the term "sexual identity" was replaced by "gender identity".[41]

On 6 November 2015, a bill to allow transgender people to legally change their gender without the need for sex reassignment surgery and forced sterilisation was approved by the French Senate.[45] On 24 May 2016, the National Assembly approved the bill.[45][46][47] MP Pascale Crozon, who introduced the bill, reminded MPs before the vote about the long, uncertain and humiliating procedures by which transgender people must go through to change their gender on their vital records. Due to differing texts, a joint session was established. On 12 July 2016, the National Assembly approved a modified version of the bill which maintained the provisions outlawing psychiatrist certificates and proofs of sex reassignment surgery, while also dropping the original bill's provision of allowing self-certification of gender.[48] On 28 September, the French Senate discussed the bill.[49] The French National Assembly then met on 12 October in a plenary session to approve the bill once more and rejected amendments proposed by the French Senate which would have required proof of medical treatment.[50][51] On 17 November, the Constitutional Council ruled that the bill is constitutional.[52][53] It was signed by the President on 18 November 2016, published in the Journal officiel the next day,[54] and took effect on 1 January 2017.[55]

Intersex rights

Intersex people in France have some of the same rights as other people, but with significant gaps in protection from non-consensual medical interventions and protection from discrimination. In response to pressure from intersex activists and recommendations by United Nations Treaty Bodies, the Senate published an inquiry into the treatment of intersex people in February 2017. An individual, Gaëtan Schmitt, is currently taking legal action to obtain "neutral sex" ("sexe neutre") classification.[56] On 17 March 2017, the President of the Republic, François Hollande, described medical interventions to make the bodies of intersex children more typically male or female as increasingly considered to be mutilations.[57]

LGBT rights movement in France

LGBT rights organisations in France include Act Up Paris, SOS Homophobie, Arcadie, FHAR, Gouines rouges, GLH, CUARH, and L'Association Trans Aide, ( Trans Aid Association, established in September 2004) and Bi'cause (bisexual).

Military service

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals are allowed to serve openly in the French Armed Forces.[58][59]

Blood donation

A circulaire from the Directorate General of Health, which dates back to 20 June 1983 at the height of the HIV epidemy, banned men who have sex with men (MSM) from donating blood. However, it was recalled by the ministerial decree on 12 January 2009.[60]

On 3 April 2015, a deputy member of the Union of Democrats and Independents, Arnaud Richard, presented an amendment against the exclusion of MSM, which was eventually adopted later in the same month.[61]

In November 2015, Minister of Health Marisol Touraine announced that gay and bisexual men in France can donate blood after 1 year of abstinence. This policy was implemented and went into effect on 10 July 2016.[62][63]

Public opinion

The Mayor of Paris between 2001 and 2014, Bertrand Delanoë, publicly revealed his homosexuality in 1998, before his first election in 2001.

In December 2006, an Ipsos-MORI Eurobarometer survey conducted showed: 62% supported same-sex marriage, while 37% were opposed; 55% believed gay and lesbian couples should not have parenting rights, while 44% believed same-sex couples should be able to adopt.[64]

In June 2011, an Ifop poll found that 63% of respondents were in favour of same-sex marriage, while 58% supported adoption rights for same-sex couples.[3] In 2012, an Ifop poll showed that 90% of the French perceived homosexuality like one way as another to live their sexuality.[65]

A 2013 Pew Research Center opinion survey showed that 77% of the French population believed homosexuality should be accepted by society, while 22% believed it should not.[4] Younger people were more accepting: 81% of people between 18 and 29 believed it should be accepted, 79% of people between 30 and 49 and 74% of people over 50.

In May 2015, PlanetRomeo, an LGBT social network, published its first Gay Happiness Index (GHI). Gay men from over 120 countries were asked about how they feel about society’s view on homosexuality, how do they experience the way they are treated by other people and how satisfied are they with their lives. France was ranked 21st, just above South Africa and below Australia, with a GHI score of 63.[66]

A 2017 Pew Research Center poll found that 73% of French people were in favour of same-sex marriage, while 23% were opposed.[67]

Overseas departments and territories

Same-sex marriage is legal in all of France's overseas departments and territories. Despite this, acceptance of homosexuality and same-sex relationships tends to be lower than in metropolitan France, as residents are in general more religious, and religion plays a bigger role in public life. In some of these territories, homosexuality is occasionally perceived as "foreign" and "practiced only by the white population".[68] The first same-sex marriages in Saint Martin and French Polynesia caused public demonstrations against such marriages.[69][70]

Of the 27 overseas deputies in the French Parliament, 11 (2 from Mayotte, 3 from Réunion, 1 from French Guiana, 1 from Guadeloupe, 1 from Martinique, 2 from New Caledonia and 1 from Saint Pierre and Miquelon) voted in favor of same-sex marriage, 11 (2 from Guadeloupe, 3 from Martinique, 3 from French Polynesia, 2 from Réunion and 1 from Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy) voted against, 1 (from French Guiana) abstained and 3 (1 each from Réunion, Guadeloupe and Wallis and Futuna) were not present during the vote.[71]

The group Let's go (French Creole: An Nou Allé) is a LGBT organization active in the French Caribbean. Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy are famous internationally for their beaches and tourist attractions, which include gay bars, discos, saunas and beaches.[72]

LGBT people in New Caledonia are widely accepted, and enjoy a large nightlife and dating scene.[73] Similarly, Réunion is known for being welcoming to LGBT people and has been described as a "gay-friendly haven in Africa". In 2007, the local tourism authorities launched a "gay-welcoming" charter in tour operators, hotels, bars and restaurants. There are famous gay beaches in Saint-Leu and L'Étang-Salé.[74] Mayotte, on the other hand, is majoritarily Muslim. This influences public perception of the LGBT community, and there have been reports of family rejections, harassment and discrimination on the island.[68] Nevertheless, the first same-sex marriage in Mayotte, the first in a majoritarily Muslim jurisdiction, was performed in September 2013 with little fanfare.[75]

The gay scene is more limited in French Guiana, though local LGBT people have reported a "growing sense of acceptance", which many attribute to French Guiana's closely knit families and communities.[76]

While French Polynesia tends to be more socially conservative, it has become more accepting and tolerant of LGBT people in recent years. In 2009, the first LGBT organization was founded in the territory, and the first LGBT event was also held that same year.[77] Furthermore, French Polynesian society has a long tradition of raising some boys as girls to play important domestic roles in communal life (including dancing, singing and house chores). Such individuals are known as the māhū, and are perceived by society as belonging to a third gender. This is similar to the fa'afafine of Samoa and the whakawāhine of New Zealand. The Tahitian term rae rae, on the other hand, refers to modern-day transsexuals who undergo medical operations to change gender. Māhū and rae rae are not to be confused, as the former is a cultural and traditional recognized Polynesian identity, while the latter encompassess contemporary transgender identity.[78]

In both Saint Pierre and Miquelon and Wallis and Futuna, the gay scene is very limited, due mostly to their small populations. Nontheless, in both territories, homosexuality tends to be accepted and there is little controversy surrounding the issue.[79][80] Wallis and Futuna, like French Polynesia, also has a traditional third gender population: the fakafafine.[81]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws concerning gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples (e.g. unregistered cohabitation, life partnership) | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Automatic parenthood on birth certificates for children of same-sex couples | |

| LGBT people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Access to IVF for lesbian couples | |

| Homosexuality declassified as an illness | |

| Transsexuality declassified as an illness | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

See also

References

- 1 2 French parliament allows gay marriage despite protests Reuters, 23 April 2013

- 1 2 3 Rainbow Europe: France

- 1 2 "Yagg". Tetu.com. 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- 1 2 "The 20 most and least gay-friendly countries in the world". GlobalPost. 26 June 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "Paris The city of Proust and Piaf is a natural environment for a flourishin". The Independent. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "Comment rejoindre l'association Les "Oublié(e)s" de la Mémoire". Devoiretmemoire.org. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Ordonnance 45–190

- ↑ "Loi n°74-631 du 5 juillet 1974 FIXANT A 18 ANS L'AGE DE LA MAJORITE" (in French). Legifrance. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "Fac-similé JO du 05/08/1982, page 02502" (in French). Legifrance. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Proceedings of the National assembly, 2nd sitting of 20 December 1981

- ↑ "Fac-similé JO du 27/11/1960, page 10603" (in French). Legifrance. 27 November 1960. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Olivier Jablonski. "1960 sous amendement Mirguet". Semgai.free.fr. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "Constitution Du 4 Octobbre 1958" (PDF). Archives.assemblee-nationale.fr. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "Loi n°80-1041 du 23 décembre 1980 RELATIVE A LA REPRESSION DU VIOL ET DE CERTAINS ATTENTATS AUX MOEURS" (in French). Legifrance. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ (in French) L'enfant dans le couple homosexuel - Avocat adoption et filiation

- ↑ "French parliament rejects gay marriage bill". Chinadaily.com.cn. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "French parliament rejects same-sex marriage bill". France 24. Agence France-Presse. 14 June 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ "Same-sex marriage bill to be introduced in France this October". Pinknews.co.uk. 26 August 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "France's parliament approve gay marriage article". BBC News. 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "France's parliament passes gay marriage bill – World – CBC News". Cbc.ca. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "Le projet de loi sur le mariage homosexuel adopté par l'Assemblée". Lemonde.fr. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ (in French) Le Sénat adopte l'article qui ouvre le mariage aux homosexuels

- ↑ "France gay marriage faces constitution threat but activists upbeat". Gay Star News. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "French lawmakers approve same-sex marriage bill". CNN International. 24 April 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ↑ Communiqué de presse – 2013-669 DC – Loi ouvrant le mariage aux couples de personnes de même sexe, Constitutional Council of France, retrieved on 17 May 2013

- ↑ Hugh Schofield (2013-05-18). "BBC News – France gay marriage: Hollande signs bill into law". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-11-21.

- ↑ (in French) LOI n° 2013-404 du 17 mai 2013 ouvrant le mariage aux couples de personnes de même sexe

- ↑ "French couple ties the knot in first same-sex wedding". CNN.com. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Sarah Begley (18 October 2013). "First Gay Adoption Approved in France". Time Magazine.

- ↑ LeMonde.fr (18 October 2013). "Première adoption des enfants du conjoint dans une famille homoparentale ("First time adoption of stepchildren in a same-sex family")". Le Monde.

- ↑ (in French) POUR OU CONTRE LA PROCRÉATION MÉDICALEMENT ASSISTÉE DANS LA LOI AUTORISANT LE MARIAGE HOMOSEXUEL ?

- ↑ (in French) La PMA, victime de l'opposition au mariage homosexuel ?

- ↑ "France to legislate on assisted reproduction: spokesman". Reuters. 28 June 2017.

- ↑ "France eyes legalizing assisted reproduction for gay women in 2018". Reuters. 12 September 2017.

- ↑ "PMA pour toutes: les Français largement favorables". Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ (in French) PMA pour toutes. Un député LREM annonce une proposition de loi

- ↑ (in French) PMA pour toutes : un député LREM espère une adoption "avant la fin 2018"

- ↑ "French high court grants new rights to gay parents - France 24". 5 July 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- 1 2 "France adds "sexual identity" to the protected grounds of discrimination / Latest news / News / Home / ilga". ILGA Europe. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- 1 2 Le Corre, Maëlle (25 July 2012). "L'"identité sexuelle" devient un motif de discrimination dans le code pénal" (in French). Yagg.

- 1 2 LOI n° 2016-1547 du 18 novembre 2016 de modernisation de la justice du XXIe siècle, 18 November 2016, retrieved 2017-11-05

- ↑ "Cour de cassation, criminelle, Chambre criminelle, 12 novembre 2008, 07–83.398, Publié au bulletin" (in French). Legifrance. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "France: Transsexualism will no longer be classified as a mental illness in France / News / Welcome to the ILGA Trans Secretariat / Trans / ilga – ILGA". Trans.ilga.org. 16 May 2009. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "Qu'est-ce qu'une affection de longue durée ?". Ameli.fr. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- 1 2 "AMENDEMENT N°282". Assemblée Nationale. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ Le Corre, Maëlle (19 May 2016). "L'Assemblée nationale adopte l'amendement visant à faciliter le changement d'état civil pour les personnes trans" (in French). Yagg.

- ↑ "Transsexuels: simplification du changement d'état civil votée par l'Assemblée nationale". Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ Fae, Jane (13 July 2016). "Transgender people win major victory in France". Gay Star News.

- ↑ (in French) Séance du 28 septembre 2016 (compte rendu intégral des débats)

- ↑ "It's official – France adopts a new legal gender recognition procedure! - ILGA-Europe". ilga-europe.org. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ (in French) Première séance du mercredi 12 octobre 2016

- ↑ (in French) Décision n° 2016-739 DC du 17 novembre 2016

- ↑ (in French) Le Conseil constitutionnel valide le projet de loi J21

- ↑ (in French) LOI n° 2016-1547 du 18 novembre 2016 de modernisation de la justice du XXIe siècle (1)

- ↑ (in French) J21 : La loi de modernisation de la Justice entre en vigueur

- ↑ Cavelier, Jeanne (2017-03-21). "Vincent Guillot : " Il faut cesser les mutilations des enfants intersexes en France "". Le Monde.fr. ISSN 1950-6244. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ↑ Ballet, Virginie (March 17, 2017). "Hollande prône l'interdiction des chirurgies sur les enfants intersexes". Libération.

- ↑ "Countries that Allow Military Service by Openly Gay People" (PDF). Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ (in French) Une militaire transgenre doit prouver son changement de sexe «irréversible»

- ↑ "Ministerial decree of 2009, Jan 12th fixing blood donor selection criteria". Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ "«Les homosexuels pourront donner leur sang, c'est un symbole fort»". Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ "France to lift ban on gay men giving blood, health minister says - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". mobile.abc.net.au. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ CNN, Susannah Cullinane and Saskya Vandoorne,. "France lifts ban on gay men as blood donors - CNN". Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ "French Public Endorse Gay Marriage". 365gay.com. 14 December 2006. Archived from the original on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ↑ "Les Français et la perception de l'homosexualité" (PDF). Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ The Gay Happiness Index. The very first worldwide country ranking, based on the input of 115,000 gay men Planet Romeo

- ↑ Religion and society, Pew Research Center, 29 May 2018

- 1 2 La haine anti-LGBT, plus virulente en Outre-mer que dans l'Hexagone, selon un rapport

- ↑ (in French) Polynésie française : le premier mariage gay dérange

- ↑ (in French) Saint-Martin. Un premier mariage gay pour la presque Friendly Island

- ↑ Mariage pour tous: le vote des députés d'Outre-mer

- ↑ Gay Life in French West Indies (Gaudeloupe, Martinique, Saint Barts, Saint Martin)

- ↑ Gay friendly destination

- ↑ Réunion: a gay-friendly stop in the Indian Ocean

- ↑ (in French) Mayotte: premier mariage gay célébré

- ↑ Mariage pour tous, la Guyane semble plus tolérante

- ↑ Tahiti découvre l'homosexualité

- ↑ RaeRae and Mahu: third polynesian gender

- ↑ Vivre gay à Wallis et Futuna?

- ↑ (in French) Premier mariage pour tous célébré à la Mairie de Saint-Pierre

- ↑ Migration, urbanisation et émergence des transgenres wallisiennes dans la ville de Nouméa

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT in France. |

Further reading

- Claudina Richards, The Legal Recognition of Same-Sex Couples: The French Perspective, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 51, No. 2 (Apr. 2002), pp. 305–324

- Gunther, Scott Eric (2009). The Elastic Closet A History of Homosexuality in France, 1942-present. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-59510-1.