Islamic Cairo

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Cairo Governorate, Egypt |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (v), (vi) |

| Reference | 89 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Area | 523.66 ha (1,294.0 acres) |

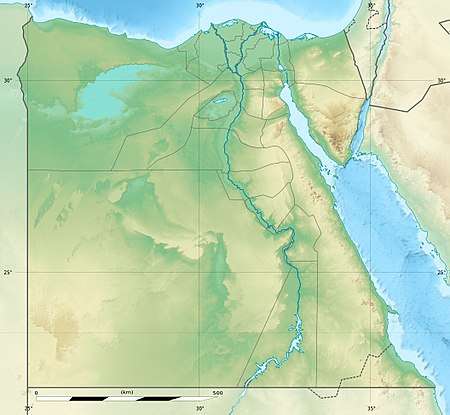

| Coordinates | 30°02′45.61″N 31°15′45.78″E / 30.0460028°N 31.2627167°ECoordinates: 30°02′45.61″N 31°15′45.78″E / 30.0460028°N 31.2627167°E |

Location of Islamic Cairo in Egypt | |

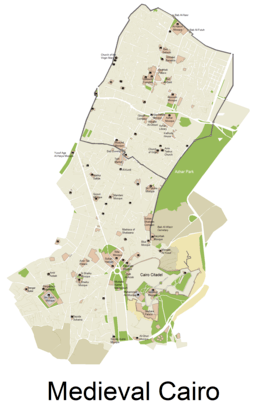

Islamic Cairo (Arabic: قاهرة المعز, Qahirat al-Maez) is a part of central Cairo around the old walled city and around the Citadel of Cairo which is characterized by hundreds of mosques, tombs, madrasas, mansions, caravanserais, and fortifications dating from the Islamic era.[1] In 1979, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) proclaimed Historic Cairo a World Cultural Heritage site, as "one of the world's oldest Islamic cities, with its famous mosques, madrasas, hammams and fountains" and "the new centre of the Islamic world, reaching its golden age in the 14th century."[2]

Historical background

Egypt was conquered by Arab Muslims under 'Amr ibn al-'As in 641. Alexandria was then the capital of Egypt. However, even though the Arabs admired Alexandria's glamor and wealth, they chose to establish a new capital on the east bank of the Nile. That site would not be separated by water from Medina, then the residence of the Caliph. Here, the 'Amr ibn al-'As Mosque was built, the first mosque in Africa. Later rulers added many additional mosques and palaces in the area around 'Amr Mosque.

Islamic Cairo, also referred to as Medieval Cairo or Fatimid Cairo, was founded in 969 as the royal enclosure for the Fatimid caliphs, while the actual economic and administrative capital was in nearby Fustat. Fustat was established by 'Amr ibn al-'As following the conquest of Egypt. Al-Askar, located in what is now Old Cairo, was the capital of Egypt from 750 to 868. Ahmad ibn Tulun established al-Qata'i as the new capital of Egypt, and it remained the capital until 905, when the Fustat once again became the capital. After Fustat was destroyed in 1168/9 to prevent its capture by the Crusaders, the administrative capital of Egypt moved to Cairo, where it has remained ever since. It took four years for the general Jawhar al-Siqilli (the Sicilian) to build Cairo and for the Fatimid Caliph al-Muizz to leave his old capital Mahdia in Tunisia and settle in the new Fatimid capital in Egypt.

After Memphis, Heliopolis, Giza and the Byzantine fortress of Babylon-in-Egypt, Fustat was a new city built as a military garrison for Arab troops. It was the closest central location to Arabia that was accessible to the Nile. Fustat became a regional center of Islam during the Umayyad period. It was where the Umayyad ruler, Marwan II, made his last stand against the Abbasids.

Later, during the Fatimid era, Al-Qahira (Cairo) was officially founded in 969 as an imperial capital just to the north of Fustat. Over the centuries, Cairo grew to absorb other local cities such as Fustat, but the year 969 is considered the "founding year" of the modern city.[3]

In 1250, the slave soldiers or Mamluks seized Egypt and ruled from their capital at Cairo until 1517, when they were defeated by the Ottomans. By the 16th century, Cairo had high-rise apartment buildings where the two lower floors were for commercial and storage purposes and the multiple stories above them were rented out to tenants.[4]

Napoleon's French army briefly occupied Egypt from 1798 to 1801, after which an Albanian officer in the Ottoman army named Muhammad Ali Pasha made Cairo the capital of an independent empire that lasted from 1805 to 1882. The city then came under British control until Egypt was granted its independence in 1922.

Notable sites

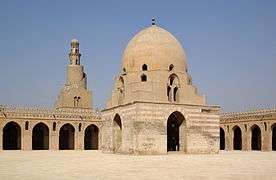

While the first mosque in Egypt was the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Fustat, the Mosque of Ibn Tulun is the oldest mosque to retain its original form and is a rare example of Abbasid architecture, from the classical period of Islamic civilization. It was built in 876–879 AD in a style inspired by the Abbasid capital of Samarra in Iraq.[5] It is one of the largest mosques in Cairo and is often cited as one of the most beautiful.[6][7]

After Cairo was founded to the northeast of Fustat in 959 AD by the victorious Fatimid army, the Fatimids built a separate palatial city which contained their palaces and institutions of government. It was enclosed by a circuit of walls, which were rebuilt in stone in the late 11th century AD by the vizir Badr al-Gamali,[8] parts of which survive today at Bab Zuwayla in the south and Bab al-Futuh and Bab al-Nasr in the north.

One of the most important and lasting institutions founded in the Fatimid period was the Mosque of al-Azhar, founded in 970 AD, which competes with the Qarawiyyin in Fes for the title of oldest university in the world.[9] Today, al-Azhar University is the foremost center of Islamic learning in the world and one of Egypt's largest universities with campuses across the country.[9] The mosque itself retains significant Fatimid elements but has been added to and expanded in subsequent centuries, notably by the Mamluk sultans Qaitbay and al-Ghuri and by Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda in the 18th century.

Other extant monuments from the Fatimid era include the large Mosque of al-Hakim, the al-Aqmar mosque, Juyushi Mosque, Lulua Mosque, and the Mosque of Salih Tala'i.

The most prominent architectural heritage of medieval Cairo, however, dates from the Mamluk period, from 1250 to 1517 AD. The Mamluk sultans and elites were eager patrons of religious and scholarly life, commonly building religious or funerary complexes whose functions could include a mosque, madrasa, khanqah (for Sufis), water distribution centers (sabils), and mausoleum for themselves and their families.[10] Among the best-known examples of Mamluk monuments in Cairo are the huge Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan, the Mosque of Amir al-Maridani, the Mosque of Sultan al-Mu'ayyad (whose twin minarets were built above the gate of Bab Zuwayla), the Sultan Al-Ghuri complex, the funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay in the Northern Cemetery, and the trio of monuments in the Bayn al-Qasrayn area comprising the complex of Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun, the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad, and the Madrasa of Sultan Barquq. It is said that a lot of the columns found in mosques were taken from the Coptic churches because of their beautiful artistic carvings and placed in mosques.

The Mamluks, and the later Ottomans, also built wikalas or caravanserais to house merchants and goods due to the important role of trade and commerce in Cairo's economy.[11] The most famous example still intact today is the Wikala al-Ghuri, which nowadays also hosts regular performances by the Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe.[12] The famous Khan al-Khalili (see below) is a commercial hub which also integrated caravanserais (also known as khans).

Islamic Cairo is also the location of several important religious shrines such as the al-Hussein Mosque (whose shrine is believed to hold the head of Husayn ibn Ali), the Mausoleum of Imam al-Shafi'i (founder of the Shafi'i madhhab, one of the primary schools of thought in Sunni Islamic jurisprudence), the Tomb of Sayyida Ruqayya, the Mosque of Sayyida Nafisa, and others.[13]

Preservation status

Much of this historic area suffers from neglect and decay, in this, one of the poorest and most overcrowded areas of the Egyptian capital.[14] In addition, as reported in the Al-Ahram Weekly, thefts at Islamic monuments inside the Darb Al-Ahmar threaten their long-term preservation.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ e.g. O'Neill, Zora et al. 2012. Lonely Planet: Egypt (11th edition).

- ↑ UNESCO, Decision Text, World Heritage Centre, retrieved 21 July 2017

- ↑ Irene Beeson (September–October 1969). "Cairo, a Millennial". Saudi Aramco World. pp. 24, 26–30. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ↑ Mortada, Hisham (2003). Traditional Islamic principles of built environment. Routledge. p. viii. ISBN 0-7007-1700-5.

- ↑ Williams, Caroline. 2008 (6th ed.). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, pp. 50–54.

- ↑ Williams, Caroline. 2008 (6th ed.). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, p 50.

- ↑ O'Neill, Zora et al. 2012. Lonely Planet: Egypt (11th edition), p. 87.

- ↑ Raymond, André. 1993. Le Caire. Fayard, p. 62.

- 1 2 Williams, Caroline. 2008 (6th ed.). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, p. 169.

- ↑ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2007. Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and its Culture. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- ↑ Raymond, André. 1993. Le Caire. Fayard, pp. 90–97.

- ↑ O'Neill, Zora et al. 2012. Lonely Planet: Egypt (11th edition), p. 81.

- ↑ Williams, Caroline. 2008 (6th ed.). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- ↑ Ancient Cairo: Preserving a Historical Heritage, Qantara, 2006.

- ↑ Unholy Thefts Archived 2013-06-05 at the Wayback Machine. Al-Ahram Weekly, Nevine El-Aref, 26 June - 2 July 2008 Issue No. 903.

External links