Mosque of Ibn Tulun

| Mosque of Ibn Tulun | |

|---|---|

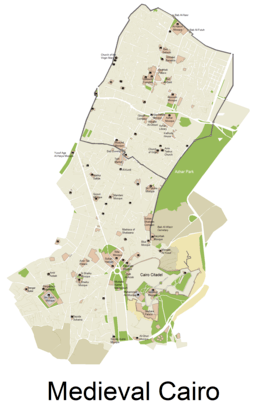

Minaret and ablution fountain (sabil) of the Ibn Tulun Mosque | |

Shown within Egypt | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Cairo, Egypt |

| Geographic coordinates | 30°01′44″N 31°14′58″E / 30.02889°N 31.24944°ECoordinates: 30°01′44″N 31°14′58″E / 30.02889°N 31.24944°E |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Year consecrated | 884 |

| Architectural description | |

| Architectural type | Mosque |

| Architectural style | Abbasid |

| Founder | Ahmed ibn Tulun |

| Completed | 879 |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 2 |

| Minaret(s) | 1 |

| Materials | brick |

The Mosque of Ibn Tulun (Arabic: مسجد إبن طولون, translit. Masjid Ibn Ṭūlūn) is located in Cairo, Egypt. It is the oldest mosque in the city surviving in its original form, and is the largest mosque in Cairo in terms of land area.

Construction history

The mosque was commissioned by Ahmad ibn Tulun, the Turkic Abbassid governor of Egypt from 868–884 whose rule was characterized by de facto independence. The historian al-Maqrizi lists the mosque's construction start date as 876 AD,[1] and the mosque's original inscription slab identifies the date of completion as AH 265 (878/879).

The mosque was constructed on a small hill called Gebel Yashkur, "The Hill of Thanksgiving." One local legend says that it is here that Noah's Ark came to rest after the Deluge, rather than at Mount Ararat.[2]

The grand congregational mosque was intended to be the focal point of Ibn Tulun's capital, al-Qata'i, which served as the center of administration for the Tulunid dynasty. Originally the mosque backed onto Ibn Tulun's palace, and a door next to the minbar allowed him direct entry to the mosque. Al-Qata'i was razed in the early 10th century AD, and the mosque is the only surviving structure.

The mosque was constructed in the Samarran style common with Abbasid constructions. It is constructed around a courtyard, with one covered hall on each of the four sides, the largest being on the side of the qibla, or direction of Mecca. The original mosque had a fountain (fauwara[3]) in the middle of the sahn, covered a gilt dome supported by ten marble columns, and round it were 16 marble columns and a marble pavement. Under the dome there was a great basin of marble 4 cubits in diameter with a jet of marble in the centre. A distinctive sabil with a high drum dome was added in the central courtyard at the end of the thirteenth century by Mamluk Sultan Lajin instead of the "fauwara".

Minaret

There is significant controversy over the date of construction of the minaret, which features a helical outer staircase similar to that of the famous minaret in Samarra. It is also told that using these stairs one can climb up on a horse. Legend has it that Ibn Tulun himself was accidentally responsible for the design of the structure: supposedly while sitting with his officials, he absentmindedly wound a piece of parchment around his finger. When someone asked him what he was doing, he responded, embarrassed, that he was designing his minaret. Many of the architectural features, however, point to a later construction, in particular the way in which the minaret does not connect well with the main mosque structure, something that would have been averted had the minaret and mosque been built at the same time. Architectural historian Doris Behrens-Abouseif asserts that Sultan Lajin, who restored the mosque in 1296, was responsible for the construction of the current minaret.[4]

Prayer niches

There are six prayer niches (mihrab) at the mosque, five of which are flat as opposed to the main concave niche.

- The main niche is situated in the centre of the qibla wall and is the tallest of the six. It was redecorated under Sultan Lajin and contains a top of painted wood, the shahada in a band of glass mosaics and a bottom of marble panels.[4]

- The same qibla wall features a smaller niche to the left of the main niche. Its stalactite work and naskhi calligraphy indicate an early Mamluk origin.[4]

- The two prayer niches on the piers flanking the dikka are decorated in the Samrarran style, with one niche containing a unique medallion with a star hanging from a chain. The Kufic shahada inscriptions on both niches do not mention Ali and were thus made before the Shi'a Fatimids came to power.[4]

- The westernmost prayer niche, the mihrab of al-Afdal Shahanshah, is a replica of an original kept at Cairo's Museum of Islamic Art. It is ornately decorated in a style with influences from Persia. The Kufic inscription mentions the Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir, on whose orders the niche was made, as well as the Shi'a shahada including Ali as God's wali after declaring the oneness of God and the prophethood of Muhammad.[4]

- On the pier to the left are the remains of a copy of al-Afdal's mihrab. It differs, however, by referring to Sultan Lajin instead of al-Mustansir, and a lack of Ali's name.[4]

- Prayer niches

Main prayer niche.

Main prayer niche. Dikka flanked by two pre-Fatimid prayer niches.

Dikka flanked by two pre-Fatimid prayer niches..jpg) Al-Afdal's mihrab in honour of al-Mustansir.

Al-Afdal's mihrab in honour of al-Mustansir.- The partially damaged "copy" on the left pier.

Outside the mosque

During the medieval period, several houses were built up against the outside walls of the mosque. Most were demolished in 1928 by the Committee for the Conservation of Arab Monuments, however, two of the oldest and best-preserved homes were left intact. The "house of the Cretan woman" (Bayt al-Kritliyya) and the Beit Amna bint Salim, were originally two separate structures, but a bridge at the third floor level was added at some point, combining them into a single structure. The house, accessible through the outer walls of the mosque, is open to the public as the Gayer-Anderson Museum, named after the British general R.G. 'John' Gayer-Anderson, who lived there until 1942.

Restoration

The mosque has been restored several times. The first known restoration was in 1177 under orders of the Fatimid vizier Badr al-Jamali. Sultan Lajin's restoration of 1296 added several improvements. The mosque was most recently restored by the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities in 2004.

In popular culture

Parts of the James Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me were filmed at the mosque. The mosque is featured in the game Serious Sam 3: BFE, forming a significant part of the game's third level.

See also

References

- ↑ al-Maqrīzī, Khiṭaṭ, II, pp. 265 ff.

- ↑ R.G. 'John' Gayer-Anderson Pasha. "Legends of the House of the Cretan Woman." Cairo and New York: American University in Cairo Press, 2001. pp. 33–34. and Nicholas Warner. "Guide to the Gayer-Anderson Museum in Cairo." Cairo: Press of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, 2003. p. 5.

- ↑ YEOMANS, RICHARD (2006). The Art & Archticture Of Islamic Cairo. 8 Southern Court; South Street Reading RG1 4QS, UK: Garnet publishing Limited. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-85964-154-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1989). "Early Islamic Architecture in Cairo". Islamic Architecture in Cairo: an Introduction. Cairo: American University in Cairo. pp. 47–57.

Works cited

- Warner, Nicholas (2005). The Monuments of Historic Cairo: a map and descriptive catalogue. Cairo: American University in Cairo.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mosque of Ibn Tulun. |

- Ibn Tulun Mosque - entry on Archnet, with full bibliography