Isaaq

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Somali, Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Sunni, Sufism) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dir, Darod, Hawiye, Rahanweyn, other Somalis |

The Isaaq (also Isaq, Ishaak, Isaac) (Somali: Reer Sheekh Isaxaaq, Arabic: إسحاق) is a Somali clan.[1] It is one of the major Somali clans, with a large and densely populated traditional territory.[2] Members principally live in Somaliland, the Somali Region of Ethiopia and Djibouti, as well as the Somali region of Kenya, where they are known as the Isahakia community.[3]

The populations of five major cities in Somaliland – Hargeisa, Burao, (second and third largest cities in Somalia respectively)[4] Berbera, Erigavo and Gabiley – are predominantly Isaaq.[5][6]

Overview

According to some genealogical books and Somali tradition, the Isaaq clan was founded in the 13th or 14th century with the arrival of Sheikh Isaaq Bin Ahmed Bin Mohammed Al Hashimi (Sheikh Isaaq) from Arabia, a descendant of Ali ibn Abi Talib in Maydh.[7][8] He settled in the coastal town of Maydh in modern-day northwestern Somaliland, where he married into the local Magaadle clan.[9]

There are also numerous existing hagiologies in Arabic which describe Sheikh Isaaq's travels, works and overall life in modern Somaliland, as well as his movements in Arabia before his arrival.[10] Besides historical sources, one of the more recent printed biographies of Sheikh Isaaq is the Amjaad of Sheikh Husseen bin Ahmed Darwiish al-Isaaqi as-Soomaali, which was printed in Aden in 1955.[11]

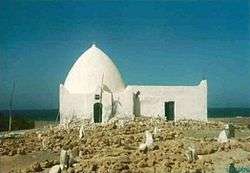

Sheikh Isaaq's tomb is in Maydh, and is the scene of frequent pilgrimages.[10] Sheikh Isaaq's mawlid (birthday) is also celebrated every Thursday with a public reading of his manaaqib (a collection of glorious deeds).[9] His Siyaara or pilgrimage is performed annually both within Somaliland and in the diaspora particularly in the Middle East among Isaaq expatriates.

Distribution

The Isaaq have a very wide and densely populated traditional territory. They live in all 5 regions of Somaliland such as Awdal, Woqooyi Galbeed, Togdheer, Sanaag and Sool. They have large settlements in the Somali region of Ethiopia, mainly on the eastern side of Somali region also known as the Hawd and formerly Reserve Area which is mainly inhabited by the Isaaq sub-clan members. They also have large settlements in both Kenya and Djibouti, making up a large percentage of the Somali population in these 2 countries respectively.[3]

The Isaaq clan constitute the largest Somali clan in Somaliland. The populations of five major cities in Somaliland – Hargeisa, Burao, Berbera, Erigavo and Gabiley – are all predominantly Isaaq.[12] They exclusively dominate the Woqooyi Galbeed region, and the Togdheer region, and form a majority of the population inhabiting the western and central areas of Sanaag region, including the regional capital Erigavo.[13] The Isaaq also have a large presence in the western and northern parts of Sool region as well,[14] with Habar Jeclo sub-clan of Isaaq living in the Aynabo district whilst the Habar Yoonis subclan lives in the eastern part of Xudun district and the very western part of Las Anod district.[15] They also live in the northeast of the Awdal region, with Sa'ad Musse sub-clan of Habar Awal being centred around Lughaya and its environs.

Lineage

Sheikh Isaaq bin Ahmed was one of the Arabian scholars that crossed the sea from Arabia to the Horn of Africa to spread Islam around 12th to 13th century. It is said that sheikh Isaaq is to have been descended of the prohet Muhammad through his daughter Fatima. Thus making the Sheikh belong to the Ashraf.

Some anthropologists specialized in Somali studies dispute this genealogy and place the Isaaq within an indigenous Somali clan framework belonging to either the Dir or Irrir sub-grouping of the Somali clan family.[16][17]

Sheikh Isaaq married two local women in Somalia that bore him eight sons. The descendants of those eight sons comprise the modern Isaaq clan.

Y-DNA

Forensic genetic testing of Isaaq clan members inhabiting Djibouti found that all of the individuals belonged to the E-V32 subclade of the paternal haplogroup E1b1b1.[18] Most Isaaq in Djibouti belong to the Habar Awal subclan.[19][20]

History

The Isaaq clan played a prominent role in the Abyssinian-Adal war (1529–1543, referred to as the "Conquest of Abyssinia") in the army of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi,[21] I. M. Lewis noted that only the Habar Magadle division (Ayoub, Garhajis, Habar Awal and Arab) of the Isaaq were mentioned in chronicles of that war written by Shihab Al-Din Ahmad Al-Gizany known as Futuh Al Habash.[22]

I. M. Lewis states:[23]

The Marrehan and the Habar Magadle [Magādi] also play a very prominent role (...) The text refers to two Ahmads's with the nickname 'Left-handed'. One is regularly presented as 'Ahmad Guray, the Somali' (...) identified as Ahmad Guray Xuseyn, chief of the Habar Magadle. Another reference, however, appears to link the Habar Magadle with the Marrehan. The other Ahmad is simply referred to as 'Imam Ahmad' or simply the 'Imam'.This Ahmad is not qualified by the adjective Somali (...) The two Ahmad's have been conflated into one figure, the heroic Ahmed Guray (...)

The first of the tribes to reach Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi were Habar Magādle of the Isaaq clan with their chieftain Ahmad Gurey Bin Hussain Al-Somali,[24] the Somali commander was noted to be one of Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi's "strongest and most able generals".[25] The Habar Magādle clan were highly appreciated and praised by the leader Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi for their bravery and loyalty.[26]

After the collapse of Adal Sultanate the Isaaq clan established successor states that split into 3 Sultanates known as Garhajis Sultanate, Habar Awal Sultanate and Habar Jeclo Sultanate. These 3 Sultanates exerted a strong centralized authority during its existence, and possessed all of the organs and trappings of an integrated modern state: a functioning bureaucracy, a hereditary nobility, titled aristocrats, a state flag, as well as a professional army.[27][28] These sultanates also maintained written records of their activities, which still exist.[29]

The Isaaq clan played a prominent role in the Dervish movement, with Sultan Nur Aman of the Habar Yoonis being fundamental in the inception of the movement. Sultan Nur was the principle agitator that rallied the dervish behind his anti-French Catholic Mission campaign that would become the cause of the dervish uprise.[30] Haji Sudi of the Habar Jeclo was the highest ranking Dervish after Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, he died valiantly defending the Taleh fort during the RAF bombing campaign.[31][32][33] The sub-clans that were highly known for joining the Dervish movement were respectively from the Habar Yoonis, Habar Jeclo, Eidagale and Arap clans. The Isaaq clans were able to purchase advanced weapons and successfully resist both British Empire and Ethiopian Empire for many years.[34]

The Isaaq clan along with other northern Somali tribes were under British Somaliland protectorate administration from 1884 to 1960. On gaining independence the Somaliland protectorate decided to form a union with Italian Somalia. The Isaaq clan spearheaded the greater Somalia quest from 1960 to 1991. However, after the collapse of the Somali Democratic Republic in 1991 the Isaaq dominated Somaliland declared independence from Somalia as a separate nation.[35]

Clan tree

In the Isaaq clan-family, component clans are divided into two uterine divisions, as shown in the genealogy. The first division is between those lineages descended from sons of Sheikh Isaaq by a Harari woman – the Habar Habuusheed – and those descended from sons of Sheikh Isaaq by a Somali woman of the Magaadle sub-clan of the Dir – the Habar Magaadle. Indeed, most of the largest clans of the clan-family are in fact uterine alliances hence the matronymic "Habar" which in archaic Somali means "mother".[36] This is illustrated in the following clan structure.[37]

A. Habar Magaadle

- Ismail (Garhajis)

- Ayub

- Muhammad (Arap)

- Abdirahman (Habar Awal)

B. Habar Habuusheed

- Ahmed (Tol-Ja’lo)

- Muuse (Habar Jeclo)

- Ibrahiim (Sanbuur)

- Muhammad (‘Ibraan)

There is clear agreement on the clan and sub-clan structures that has not changed for centuries the oldest recorded genealogy of a Somali in Western literature was by Sir Richard Burton in 1853 regarding his Isaaq host the Sultan of Zeila Sharmarka Ali Saleh,[38] the most famous nineteenth century Somali.

The following listing is taken from the World Bank's Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics from 2005 and the United Kingdom's Home Office publication, Somalia Assessment 2001.[39][40]

- Isaaq

- Habar Awal

- Issa Muuse

- Sa’ad Muuse

- Garhajis

- Habar Yoonis

- Eidagale

- Arap

- Ayub

- Habar Jeclo

- Muuse Abokor

- Mohamed Abokor

- Samane Abokor

- Toljecle

- Sanbuur

- Imraan

- Habar Awal

One tradition maintains that Isaaq had twin sons: Ahmed or Arap, and Ismail or Gerhajis.[41]

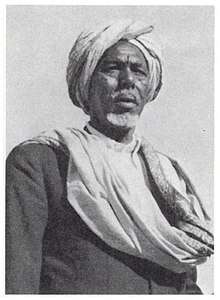

Nineteenth century Isaaq notables

- Sharmaarke Ali Saleh 1797–1861, governor of Berbera, Zeila and Tajoura 1833–1861.[42][43][44][45]

Sultan Abdurahman Deria of the Habr Awal Isaaq receiving honours from Queen Elizabeth II in Aden

Sultan Abdurahman Deria of the Habr Awal Isaaq receiving honours from Queen Elizabeth II in Aden

Little is known how Sharmaarke took over the administration of Berbera. But by 1843 when Lieutenant. Curttenden visited Somaliland Sharmaarke was the governor of Berbera. A decade earlier when Frederic Forbes visited Berbera in 1833 Sharmaarke was already well established on the Somali coast.

" In 1842 the Sheriff of Mocha subjected himself and his possession including Zeila, to the Porte; he was made Ottoman pasha of western Arabia, and Zeila theoretically returned to Turkey. On the spot however, the situation was more complex for in 1843 Haji Sharmaarke from Berbera sized Zeila, imprisoned the Shariff's garrison and offered to put the port under British protection ; the government of India rejected the offer on the ground that Aden was merely a depot for coals and that any intervention in the affairs of the African coast would be expensive and unprofitable and might excite the jealousy of other European powers. Sharmaarke's object seems to have been to make himself ruler of the Somali coast; finding that the British would not serve his purpose he apparently submitted as a governor of Zeila to the Turks who dismissed Shariff's Hussain and occupied Mocha in 1849. He intrigued with the Turks to get Berbera placed under the Turkish flag, but with no result.".[46]

“The Governor of Zaila, El Hajj Shermarkay bin Ali Salih, is rather a remarkable man. He is sixteenth, according to his own account, in descent from Ishak El Hazrami, the saintly founder of the great Garhajis and Awal tribes. Originally the Nacoda, or Captain of the native craft, he has raised himself, chiefly by British influence, to the chieftainship of his tribe (a clan of the Habr Garhajis). As early as May 1825, he received from Captain Bagnold, then our Resi- dent at Mocha, a testimonial and a reward for a severe sword wound in the left arm, received whilst defending the lives of English seamen. He went afterwards to Bombay, where he was treated with consideration; and about fifteen years ago he succeeded the Sayyid Mohamud El Barr as Governor of Zaila and its dependencies, under the Ottoman Pasha in Western Arabia.“The climate of Zaila is cooler than that of Aden, and the site being open all round, it is not so unhealthy. Mand spare roomand enclosed by the town walls. Zaila commands the adjacent harbour of Tajurrah, and is by position and northern part of Aussa (the ancient capital of Adel)and Harar, and of southern Abyssinia. It sends caravans northwards to the Dankali, and south-westwards throand the Easa and Gadabursi tribes, as far as Efat and Gurague. It is visited by Kafilas from Abyssinia, and the different races of Bedouins extending from the hills to and sea-board. The exports are valuable slaves, ivory, hides, honey, clarified butter and gums: the coast aboundsthe sponge, coral, and small pearls, which Arab divers coabout in the fair season. In the harbour I found about native craft, large and small; of these, ten belonged to the Governor. They trade with Berbera, Arabia, and Western India and are navigated by “Rajpoot” or "Hindoo pilots."[47]

- Aden Ahmed Dube "Gabay Xoog" circa 1821–1916.

One of the greatest Somali nineteenth century poet. A composer of over 300 poems spanning a period of over 60 years. His poetry can be summarized as a history in verse of all major tribal politics of the 19th century in northern Somali regions, his poetic duel with Somali poets such Hassan Dalab and Raghe Ugaz in addition to numerous Sufi poetry composed at end of his life is among his classics.[48][49]

Isaaq people

- Abdillahi Suldaan Mohammed Timacade, known as 'Timacade', a famous poet during the pre- and post-colonial periods

- Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur,Last Somali National Movement chairman and First President of Somaliland

- Abdirahim Abbey Farah, former United Nations Under-Secretary General

- Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi, Speaker of the House of Representatives of Somaliland and the Chairman of Wadani political party.

- Abdullahi Qarshe, Somali musician, poet and playwright; known as the "Father of Somali music"

- Abdul Majid Hussein, Economist, Former Permanent Representative of Ethiopia to the United Nations, 2001–2004. Leader of Ethiopian Somali Democratic League (ESDL) party in the Somali Region of Ethiopia from 1995 to 2001.

- Ahmed Hasan Awke, Somali journalist and broadcaster. He was a veteran of the BBC World Service, the Voice of America, Somaliland National TV, Horn Cable Television, Radio Mogadishu and Universal TV among also being the presidential spokesman of Siad Barre during his Military Junta.[51]

- Ahmed Guray, commander of the Isaaq Habar Magadle troops during the Abyssinian-Adal war.[24]

- Abdurrahman Mahmoud Aidiid, He is the current Mayor of Hargeisa, the capital of the autonomous Somaliland region in northwestern Somalia.

- Ahmad Girri bin Husain, Right hand partner of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi and a high ranking Adal Sultanate general who lead a large army against the Abyssinian empire.[24]

- Ahmed Yusuf Yasin, was the Vice-President of Somaliland from 2002 until 2010. and the second chairman of UDUB party.

- Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud, Former President of Somaliland from June 2010 to December 2017, fourth and longest-serving Chairman of the Somali National Movement, and former Chairman of the Kulmiye Party

- Amina Moghe Hersi (b. 1963), Award-winning Somali entrepreneur who has launched several multimillion-dollar projects in Kampala, Uganda

- Ali Abdi Farah, Former Minister of Communication and Culture in Djibouti

- Ali Feiruz, popular musician in Djibouti and Somalia

- Bashir Yussuf, Somali religious leader

- Edna Adan Ismail, first female Foreign Minister of Somaliland, has been called "The Muslim Mother Teresa" for her charity work and activism for women and girls

- Elmi Boodhari, famous Somali poet and pioneer in the genre of Somali love poems.

- Faysal Ali Warabe, Chairman of the For Justice and Development party of Somaliland (UCID).

- Fowsiyo Yusuf Haji Adan, former Foreign Minister of Somalia and MP in Federal Parliament

- Gaarriye (born Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac; 1949 – 30 September 2012), poet

- Hadrawi, poet and philosopher; author of Halkaraan; also known as the "Somali Shakespeare"

- Haji Sudi, One of the founders of the Somali Dervish movement

- Hanan Ibrahim, gender activist and first Somali British to be awarded Member of British Empire (MBE) for community work in UK

- Hussein Arab Isse, the Minister of Defence and the Deputy Prime Minister of Somalia from 20 July 2011 to 4 November 2012

- Hussain Bisad, is one of the tallest men in the world, at 2.32 m (7 ft 7 1⁄2 in). He has the largest hand span of anyone alive

- Ibrahim Dheere, Considered to be the first Somali billionaire and richest Somali person in the world with an estimated net worth of 1.8 billion US Dollars.[52]

- Ismail Mahmud Hurre, foreign minister of the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia from mid-2006 to early 2007

- Ismail Ali Abokor, former Vice-President of the Somali Democratic Republic[53]

- Jamal Ali Hussein, Somali Economist, Politician and Former Presidential Candidate of UCID party.

- Jama Mohamed Ghalib, former Police Commissioner of the Somali Democratic Republic, Secretary of Interior, Minister of Labor and Social Affairs, Minister of Local Government and Rural Development, Minister of Transportation, and Minister of Interior.

- Jama Musse Jama (b. 1967), prominent Somali ethnomathematician and author.

- Mo Farah, British 4 time Olympic gold medalist and the most decorated athlete in British athletics history.[54]

- Mohammed Abdillahi Kahin 'Ogsadey', A Somali business tycoon based in Ethiopia, where he established MAO Harar Horse, the first African corporation to export coffee and amassed a net worth of approximately $3 Billion Ethiopian Birr.[55]

- Mohamed Hasan Abdullahi, former Chief of Staff of the Somaliland Armed Forces

- Mohamed Omar Arte, former Deputy Prime Minister of Somalia.

- Mohammed Ahmed, Somali-Canadian long-distance runner and Olympian

- Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal, former Prime Minister of Somalia July 1960, July 1967– November 1969; former President of Somaliland from May 1993 to May 2002.

- Mohamed Abdullahi Omaar, former Foreign Minister of Somalia

- Mohammed Ahamed, Norwegian-Somalian association footballer currently playing in the Tippeligaen for Tromsø IL. He plays as a Center Forward

- Mohamed Hasan Abdullahi, former Chief of Staff of Somaliland Armed Forces

- Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame 'Hadrawi', poet and philosopher; author of Halkaraan; also known as the "Somali Shakespeare"

- Mohamed Mooge Liibaan, Mooge is regarded by many Somalis to be one of the greatest Somali musicians to have ever lived

- Muhammad Hawadle Madar, former Prime Minister of Somalia from 3 September 1990 to 24 January 1991.

- Muse Bihi Abdi, Current President of Somaliland since December 2017, and a former fighter pilot for the then Somali Air Force who took part in the Ogaden War; providing air support to the then-21st Division of the Somali Army. Later joined the rebel Somali National Movement (SNM)

- Musa Haji Ismail Galal, a Somali writer, scholar, linguist, historian and polymath

- Nuh Ismail Tani, current Chief of Staff of the Somaliland Armed Forces

- Rageh Omaar, Somali-British journalist and writer. He used to be a BBC world affairs correspondent, In September 2006, he moved to a new post at Al Jazeera English, and as of 2017 is currently with ITV News

- Sultan Nur, Sultan of the Habr Yunis and one of the founders of the Somali Dervish movement

- Umar Arteh Ghalib, former Prime Minister of Somalia 1991–1993. Brought Somalia into the Arab League in 1974 during his term Foreign Minister of Somalia from 1969 to 1977. Former president of UN Security Council, teacher and poet

Abusite founder of daallo airline and former minister of religious affairs in Somalia

References

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9fAjtruUXjEC&pg=PA102&dq=isaaq+noble&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiy3pWd7arZAhXmLsAKHVPFAu0Q6AEIJzAA#v=onepage&q=isaaq%20noble&f=false

- ↑ Ethnic Groups (Map). Somalia Summary Map. Central Intelligence Agency. 2002. Retrieved 2012-07-30. Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection – N.B. Various authorities indicate that the Isaaq is among the largest Somali clans , .

- 1 2 Gitonga, By Antony. "Community takes over 'ancestral land'". The Standard. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- ↑ Tekle, Amare (1994). Eritrea and Ethiopia: From Conflict to Cooperation. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 9780932415974.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=M6NI2FejIuwC&pg=PA137&dq=erigavo+isaaq+clan+population&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiY9qDunbXPAhWMDywKHf0CBHwQ6AEIJjAC#v=onepage&q=erigavo%20isaaq%20clan%20population&f=false

- ↑ Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Somalia: Information on the ethnic composition in Gabiley (Gebiley) in 1987–1988, 1 April 1996, SOM23518.E [accessed 6 October 2009]

- ↑ Rima Berns McGown, Muslims in the diaspora, (University of Toronto Press: 1999), pp. 27–28

- ↑ I.M. Lewis, A Modern History of the Somali, fourth edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2002), p. 22

- 1 2 I.M. Lewis, A Modern History of the Somali, fourth edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2002), pp. 31 & 42

- 1 2 Roland Anthony Oliver, J. D. Fage, Journal of African history, Volume 3 (Cambridge University Press.: 1962), p.45

- ↑ I. M. Lewis, A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p.131.

- ↑ Somaliland: With Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia By Philip Briggs. Google Books.

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Report on the Fact-finding Mission to Somalia and Kenya (27 October – 7 November 1997)". Refworld. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ↑ https://www.york.ac.uk/media/prdu/documents/publications/Beyond%20Fragility-a%20conflict%20and%20education%20analysis%20of%20the%20Somali%20context.pdf

- ↑ https://www.ecoi.net/file_upload/1226_1457606427_easo-somalia-security-feb-2016.pdf

- ↑ J., Abbink, (2009). The total Somali clan genealogy. African Studies Centre. OCLC 650591939.

- ↑ GILKES, P. (1996-10-01). "Blood and Bone: The call of kinship in Somalia society". African Affairs. 95 (381): 628–629. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007787. ISSN 0001-9909.

- ↑ Iacovacci, Giuseppe; et al. (2017). "Forensic data and microvariant sequence characterization of 27 Y-STR loci analyzed in four Eastern African countries". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 27: 123–131. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.12.015. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000, Guido Ambroso". UNHCR. Retrieved 2018-09-23.

- ↑ Imbert-Vier, Simon (2011). Tracer des frontières à Djibouti: des territoires et des hommes aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 9782811105068.

- ↑ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 9780852552803.

- ↑ The Galla in Northern Somaliland, I. M. Lewis, p. //dspace-roma3.caspur.it/bitstream/2307/4913/1/The%20Galla%20in%20northern%20Somaliland.pdf;jsessionid=F28E001218E0DFF229E2CBFF6E361652

- ↑ Morin, Didier (2004). Dictionnaire historique afar: 1288–1982 (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 9782845864924.

- 1 2 3 "مخطوطات > بهجة الزمان > الصفحة رقم 17". makhtota.ksu.edu.sa. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ↑ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 9780852552803.

- ↑ "مخطوطات > بهجة الزمان > الصفحة رقم 16". makhtota.ksu.edu.sa. Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- ↑ Horn of Africa, Volume 15, Issues 1–4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.

- ↑ Michigan State University. African Studies Center, Northeast African studies, Volumes 11–12, (Michigan State University Press: 1989), p.32.

- ↑ Sub-Saharan Africa Report, Issues 57–67. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 1986. p. 34.

- ↑ Foreign Department-External-B, August 1899, N. 33-234, NAI, New Delhi, Inclosure 2 in No. 1. And inclosure 3 in No. 1.

- ↑ Sun, Sand and Somals – Leaves from the Note-Book of a District Commissioner.By H. Rayne,

- ↑ Correspondence respecting the Rising of Mullah Muhammed Abdullah in Somaliland, and consequent military operations,1899–1901.pp.4–5.

- ↑ Official history of the operations in Somaliland, 1901–04 by Great Britain. War Office. General Staff Published 1907.p.56

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=pybXAAAAMAAJ&q=Isaaq+dervish&dq=Isaaq+dervish&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwicseHo86zZAhVEW8AKHfiqCh0Q6AEIVjAJ

- ↑ "History". Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=yoMBQCr4LysC&redir_esc=y

- ↑ I. M. Lewis, A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p. 157.

- ↑ "From fine to a failed state". Africa Review. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ↑ Worldbank, Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics, January 2005, Appendix 2, Lineage Charts, p. 55 Figure A-1

- ↑ Country Information and Policy Unit, Home Office, Great Britain, Somalia Assessment 2001, Annex B: Somali Clan Structure Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine., p. 43

- ↑ Laurence, Margaret (1970). A Tree for Poverty: Somali Poetry and Prose. Hamilton: McMaster University. p. 145. ISBN 1-55022-177-9.

Then Magado, the wife of Ishaak had only two children, baby twin sons, and their names were Ahmed, nick-named Arap, and Ismail, nick-named Garaxijis .

- ↑ The Visit of Frederick Forbes to the Somali Coast in 1833 R Bridges. Int J Afr Hist Stud 19 (4), 679–691. 1986.

- ↑ Travels in Southern Abyssinia Through The Country of Adal to the Kingdom of Shoa. by Charles Johnston, Volume 1. 1844

- ↑ First footsteps in East Africa : or, An exploration of Harar by Burton, Richard Francis, Sir, 1821–1890; Burton, Isabel, Lady, Published 1894

- ↑ Marston, Thomas E. Britain's Imperial Role in the Red Sea Area, 1800–1878. Hamden: Conn., Shoe String Press, 1961.

- ↑ Britain's imperial Role....pp.108–9. Ibid, p .149 ibid, p.161

- ↑ Britain's imperial Role....pp.108–9. Ibid, p .149 ibid, p.161

- ↑ Bollettino della Società geografica italiana By Società geografica italiana. 1893.

- ↑ Somalia e Benadir: viaggio di esplorazione nell'Africa orientale. Prima traversata della Somalia, compiuta per incarico della Societá geografica italiana. Luigi Robecchi Bricchetti. 1899. The Somalis in general have a great inclination to poetry; a particular passion for the stories, the stories and songs of love.

- ↑ Bollettino della Società geografica italiana. ... 1893 (ser.3, vol. 5). p.372

- ↑ http://www.somalilandinformer.com/somaliland/somaliland-prominent-somali-journalist-ahmed-hasan-awke-passes-away-in-jigjiga/

- ↑ http://www.somalilandinformer.com/somaliland/breaking-ibrahim-dheere-tycoon-passes-away-in-djibouti/

- ↑ Mohamed Yusuf Hassan, Roberto Balducci (ed.) (1993). Somalia: le radici del futuro. Il passaggio. p. 33. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "Mo Farah's family cheers him on from Somaliland village". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ "Somali Entrepreneurs". Salaan Media. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2018.