Somali Armed Forces

| Somali Armed Forces | |

|---|---|

|

Xoogga Dalka Soomaaliyeed القوات المسلحة الصومالية | |

Emblem of the Somali Armed Forces | |

| Founded | 1960 |

| Service branches |

Somali National Army[1] Somali Air Force[1] Somali Navy[1] |

| Headquarters | Mogadishu, Somalia |

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-Chief | Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed |

| Minister of Defense | Mohamed Mursal Sheikh Abdurahman |

| Chief of Army | Lt. Gen Abdiwali Hussien Jama[2] Garod[3] |

| Manpower | |

| Military age | 18 |

| Available for military service |

2,260,175 (2010 est.; males) 2,159,293 (2010 est.; females), age 18–49 |

| Fit for military service |

1,331,894 (2010 est.; males) 1,357,051 (2010 est.; females), age 18–49 |

| Reaching military age annually |

101,634 (2010 est.; males) 101,072 (2010 est.; females) |

| Active personnel | 36,000 |

| Reserve personnel | 0 |

| Expenditures | |

| Percent of GDP | 0.9% (2005) |

| Industry | |

| Foreign suppliers |

|

| Related articles | |

| Ranks | Military ranks of Somalia |

The Somali National Armed Forces (SNAF) are the military forces of Somalia, officially known as the Federal Republic of Somalia.[4] Headed by the President as Commander in Chief, they are constitutionally mandated to ensure the nation's sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity.[5] Before the Somali civil war broke out, Somalia had the largest and strongest army in the African continent until the collapse of the central government during 1991.

The SAF was initially made up of the Army, Navy, Air Force and Police Force.[6] In the post-independence period, it grew to become among the larger militaries in Africa.[7] Due to Barre's increasing reliance on his own clans, repressive policies, and the Somali Rebellion, the military had by 1988 begun to disintegrate.[8] By the time President Siad Barre fled in 1991, the armed forces had dissolved.[9] As of January 2014, the security sector is overseen by the Federal Government of Somalia's Ministry of Defence, Ministry of National Security, and Ministry of Interior and Federalism.[10] The Somaliland, Puntland and Galmudug regional governments maintain their own security and police forces.

History

Middle Ages to colonial period

Historically, Somali society conferred distinction upon warriors (waranle) and rewarded military acumen. All Somali males were regarded as potential soldiers, except for the odd religious cleric (wadaado).[11] Somalia's many Sultanates each maintained regular troops. In the early Middle Ages, the conquest of Shewa by the Ifat Sultanate ignited a rivalry for supremacy with the Solomonic dynasty.

Many similar battles were fought between the succeeding Sultanate of Adal and the Solomonids, with both sides achieving victory and suffering defeat. During the protracted Ethiopian-Adal War (1529–1559), Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi defeated several Ethiopian Emperors and embarked on a conquest referred to as the Futuh Al-Habash ("Conquest of Abyssinia"), which brought three-quarters of Christian Abyssinia under the power of the Muslim Adal Sultanate.[12][13] Al-Ghazi's forces and their Ottoman allies came close to extinguishing the ancient Ethiopian kingdom, but the Abyssinians managed to secure the assistance of Cristóvão da Gama's Portuguese troops and maintain their domain's autonomy. However, both polities in the process exhausted their resources and manpower, which resulted in the contraction of both powers and changed regional dynamics for centuries to come. Many historians trace the origins of hostility between Somalia and Ethiopia to this war.[14] Some scholars also argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms such as the matchlock musket, cannons and the arquebus over traditional weapons.[15]

At the turn of the 20th century, the Majeerteen Sultanate, Sultanate of Hobyo, Warsangali Sultanate and Dervish State employed cavalry in their battles against the imperialist European powers during the Campaign of the Sultanates.

In Italian Somaliland, eight "Arab-Somali" infantry battalions, the Ascari, and several irregular units of Italian officered dubats were established. These units served as frontier guards and police. There were also Somali artillery and zaptié (carabinieri) units forming part of the Italian Royal Corps of Colonial Troops from 1889 to 1941. Between 1911 and 1912, over 1,000 Somalis from Mogadishu served as combat units along with Eritrean and Italian soldiers in the Italo-Turkish War.[16] Most of the troops stationed never returned home until they were transferred back to Italian Somaliland in preparation for the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.[17]

In 1914, the Somaliland Camel Corps was formed in the British Somaliland protectorate and saw service before, during, and after the Italian invasion of the territory during World War II.[11]

1960 to 1991

Just prior to independence in 1960, the Trust Territory of Somalia established a national army to defend the nascent Somali Republic's borders. A law to that effect was passed on 6 April 1960. Thus the Somali Police Force's Mobile Group (Darawishta Poliska or Darawishta) was formed. 12 April 1960 has since been marked as Armed Forces Day.[18] British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland, and the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somaliland) followed suit five days later.[19] On 1 July 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic.[20]

After independence, the Darawishta merged with the former British Somaliland Scouts to form the 5,000 strong Somali National Army.[21] The new military's first commander was Colonel Daud Abdulle Hirsi, a former officer in the British military administration's police force, the Somalia Gendarmerie.[11] Officers were trained in the United Kingdom, Egypt and Italy. Despite the social and economic benefits associated with military service, the armed forces began to suffer chronic manpower shortages only a few years after independence.[22]

Merging British and Italian Somaliland caused political controversy. The distribution of power between the two regions and among the major clans in both areas was a bone of contention. In December 1961, a group of British-trained northern non-commissioned officers in Hargeisa revolted after southern officers took command of their units.[23] The rebellion was put down by other northern Noncommissioned officers (NCOs), although dissatisfaction in the north lingered.[24] Adam notes that in the aftermath of this mutiny, first commander of the armed forces General Daud Abdulle Hirsi (Hawiye/Abgaal) placed the most senior northerner, General Ainashe, as head of the army in the north.[25]

The force was expanded and modernized after the rebellion with the assistance of Soviet and Cuban advisors. The Library of Congress writes that '[i]n 1962 the Soviet Union agreed to grant a US$32 million loan to modernise the Somali army, and expand it to 14,000 personnel. Moscow later increased the amount to US$55 million. The Soviet Union, seeking to counter United States influence in the Horn of Africa, made an unconditional loan and fixed a generous twenty-year repayment schedule.'

The army was tested in 1964 when the conflict with Ethiopia over the Somali-inhabited Ogaden erupted into warfare. On 16 June 1963, Somali guerrillas started an insurgency at Hodayo, in eastern Ethiopia, a watering place north of Werder, after Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie rejected their demand for self-government in the Ogaden. The Somali government initially refused to support the guerrilla forces, which eventually numbered about 3,000. However, in January 1964, after Ethiopia sent reinforcements to the Ogaden, Somali forces launched ground and air attacks across the border and started providing assistance to the guerrillas. The Ethiopian Air Force responded with punitive strikes across its southwestern frontier against Feerfeer, northeast of Beledweyne and Galkayo. On 6 March 1964, Somalia and Ethiopia agreed to a cease-fire. At the end of the month, the two sides signed an accord in Khartoum, Sudan, agreeing to withdraw their troops from the border, cease hostile propaganda, and start peace negotiations. Somalia also terminated its support of the guerrillas.[11]

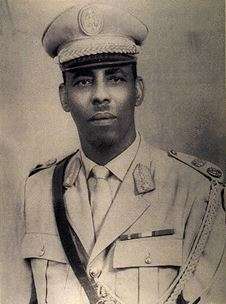

During the power vacuum that followed the assassination of Somalia's second president, Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, the military staged a coup d'état on 21 October 1969 (the day after Shermarke's funeral) and took over office.[26] Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who had succeeded Hersi as Chief of Army in 1965,[11] was installed as President of the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC), the new government of Somalia.[26] The country was renamed the Somali Democratic Republic. In 1971, he announced the regime's intention to phase out military rule.

In 1972, the National Security Court, headed by admiral Mohamed Gelle Yusuf, ordered the execution of Siad Barre's fellow coup instigators, Major General Mohamed Aynanshe Guleid (who had become the Vice President), Brigadier General Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Lieutenant Colonel Abdulkadir Dheel Abdulle.[27]

The U.S. Army Area Handbook wrote in 1976:[28]

In mid-1976 the military command structure was simple and direct. Major General Samantar was not only commander of the National Army – and therefore commander of the organizationally subordinated navy and air force- but also secretary of state for defence and a vice president of SRC and thus a member of the major decision-making body of the government. Holding the two highest.. posts, he stood alone in the command structure between the army and President Siad, the head of state. When in July 1976 the SRC relinquished its power to the newly appointed SSRP, Samantar retained the portfolio of the Ministry of Defense. The country's real power appeared to be in the SSRP's Politburo, of which Samantar became a vice president. Before the military coup, command channels ran directly from the commander of the National Army to army sector commanders who exercised authority over military forces.. in the field, and by 1986 combat units had been reorganized along Soviet lines. There is no indication that either the chain of command to lower echelons or the organisation of combat units has changed significantly since the coup.

In July 1976, the International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated the army consisted of 22,000 personnel, 6 tank battalions, 9 mechanised infantry battalions, 5 infantry battalions, 2 commando battalions, and 11 artillery battalions (5 anti-aircraft).[29] Two hundred T-34 and 50 T-54/55 main battle tanks had been estimated to have been delivered. The IISS emphasised that 'spares are short and not all equipment is serviceable.' The U.S. Army Area Handbook for Somalia, 1977 edition, agreed that the army comprised six tank and nine mechanised infantry battalions, but listed no infantry battalions, the two commando battalions, and 10 total artillery (five field and five anti-aircraft) battalions. (Kaplan et al., DA Pam 550-86, Second Edition, 1977, p. 315)

Three divisions (the 21st, 54th, and 60th)[30] were formed, and later took part in the Ogaden War. While the IISS did not list them in July 1976, there is evidence that they were formed as early as 1970 or earlier: Mohamud Muse Hersi has been listed by somaliaonline.com as commander of the 21st Division from 1970 to 1972,[31] and Muse Hassan Sheikh Sayid Abdulle as commander 26th Division in 1970–71.

Under the leadership of General Abdullah Mohamed Fadil, Abdullahi Ahmed Irro and other senior Somali military officials formulated a plan of attack for what was to become the Ogaden War in Ethiopia.[32] This was part of a broader effort to unite all of the Somali-inhabited territories in the Horn region into a Greater Somalia (Soomaaliweyn).[33] At the start of the offensive, the SNA consisted of 35,000 soldiers,[34] and was vastly outnumbered by the Ethiopian forces. Somali national army troops seized the Godey Front on 24 July 1977, after the 60th Division defeated the Ethiopian 4th Infantry Division.[35] Godey's capture allowed the Somali side to consolidate its hold on the Ogaden, concentrate its forces, and advance further to other regions of Ethiopia.[36] The invasion reached an abrupt end with the Soviet Union's sudden shift of support to Ethiopia, followed by almost the entire communist world siding with the latter. The Soviets halted supplies to Barre's regime and instead increased the distribution of aid, weapons, and training to Ethiopia's newly communist Derg regime. General Vasily Ivanovich Petrov was assigned to restructure the Ethiopian Army.[37] The Soviets also brought in around 15,000 Cuban troops to assist the Ethiopian military. By 1978, the Somali forces were pushed out of most of the Ogaden, although it would take nearly three more years for the Ethiopian Army to gain full control of Godey.[36]

Following the 1977–78 Ogaden campaign, Abudwak became the base for the SNA's 21st Division.[38]

The shift in support by the Soviet Union motivated the Barre regime to seek allies elsewhere. It eventually settled on Russia's Cold War arch-rival, the United States, which had been courting the Somali government for some time. The U.S. eventually gave extensive military support. Following the disastrous Ogaden War, Barre's government began arresting government and military officials under suspicion of participation in the abortive 1978 coup d'état.[32][39] Most of the people who had allegedly helped plot the putsch were summarily executed.[40] However, several officials managed to escape abroad where they formed the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), the first of various dissident groups dedicated to ousting Barre's regime by force.[41] Among these opposition movements were the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM) and Somali Democratic Alliance (SDA), a Gadabuursi group which had been formed in the northwest to counter the Somali National Movement (SNM) Isaaq militia.[42]

The armed forces continued to expand after the 1977-8 war. The army expanded to 96,000 in 1980, of which combat forces made up 60,000. Thereafter the army grew to 115,000 and eventually to 123,000 by 1984/85.[43]

In 1981 one of three corps headquarters for the ground forces was situated at Hargeisa in the northwestern Woqooyi Galbeed region. Others were believed to be garrisoned at Gaalkacyo in the north-central Mudug region and at Beled Weyne in the south-central Hiiraan region. The ground forces were tactically organized into seven divisions. Allocated among the divisions were three mechanized infantry brigades, ten anti-aircraft battalions, and thirteen artillery battalions.[6]

In 1984, the government attempted to solve the manpower shortage problem by instituting obligatory military service.[22] Men of eighteen to forty years of age were to be conscripted for two years. Opposition to conscription and to the campaigns against guerrilla groups resulted in widespread evasion of military service. As a result, during the late 1980s the government normally met manpower requirements by impressing men into military service. This practice alienated an increasing number of Somalis, who wanted the government to negotiate a peaceful resolution of the conflicts that were slowly destroying Somali society.

However, as the 1980s wore on, Siad Barre increasingly used clanism as a political resource.[44] Barre filled the key positions in the army and security forces with members of three Darood clans closely related to his own reer: the Marehan, Dulbahantes, and Ogaadeens.[45] Adam says that '..As early as 1976, when Colonel Omar Mohamed Farah was asked to train and command a tank brigade stationed in Mogadishu, he found that out of about 540 soldiers, at least 500 were from the Marehan clan. The whole tank division was headed by a Marehan officer, Umar Haji Masala.'[46] Compagnon wrote in 1992: "Colonels and generals were part of the president's personal patronage network; they had to remain loyal to him and his relatives, whether they had command or were temporarily in the cabinet."[47] As a result, by 1990 many Somalis looked upon the armed forces as Siad Barre's personal army. This perception eventually destroyed the military's reputation as a national institution. The critical posts of commander of the 2nd Tank Brigade and 2nd Artillery Brigade in Mogadishu were both held by Marehan officers, as were the posts of commander of the three reserve brigades in Hargeisa in the north.[48]

By 1987 the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency estimated the army was 40,000 strong (with Ethiopian army strength estimated at the same time as 260,000).[49] The President, Mohamed Siad Barre, held the rank of Major General and acted as Minister of Defence. There were three vice-ministers of national defence. From the SNA headquarters in Mogadishu four sectors were directed: 26th Sector at Hargeisa, 54th Sector at Garowe, 21st Sector at Dusa Mareb, and 60th Sector at Baidoa. Thirteen divisions, averaging 3,300 strong, were divided between the four sectors – four in the northernmost and three in each of the other sectors. The sectors were under the command of brigadiers (three) and a colonel (one). Mohammed Said Hersi Morgan has been reported as 26th Sector commander from 1986 to 1988. Walter S. Clarke seemed to say that Barre's son [Maslah Siad] was commanding the 77th Sector in Mogadishu in November 1987.[50]

By the mid-1980s, more resistance movements supported by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration had sprung up across the country. Barre responded by ordering punitive measures against those he perceived as locally supporting the guerillas, especially in the northern regions. The clampdown included bombing of cities, with the northwestern administrative center of Hargeisa, a Somali National Movement (SNM) stronghold, among the targeted areas in 1988.[51]

Compagnon writes that:[52]

From the summer of 1988 onwards, there was a combination of political repression against targeted clans and private use of violence by predatory units and individuals of the former 'national' armed forces – already in the process of disintegration – who used their power to rape, kill, and loot freely. The ..distinction between private illegitimate violence and public coercion disappeared. Many former military men later joined the clan militias or the armed gangs.

Military exercises between the United States and the Siad Barre regime continued during the 1980s. 'Valiant Usher '86' took place during the U.S. fiscal year of 1986, but actually in late 1985, and the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit participated in Exercise Eastern Wind in August 1987 in the area of Geesalay.[53] U.S. Army elements conducted training with the Somali 31st Commando Brigade at Baledogle Airfield outside Mogadishu in 1989.[54]

As of 1 June 1989, the International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated that the Army comprised four corps and 12 division headquarters.[55] At the time, the military had decreased considerably in size.[56] The IISS noted that these formations 'were in name only; below establishment in units, men, and equipment. Brigades were of battalion size.'[55] Units and formations listed in 1990 within six military sectors included the twelve divisions, four tank brigades, 45 mechanized and infantry brigades, 4 commando brigades, 1 surface-to-air missile brigade, 3 field artillery brigades, 30 field battalions, and one air defence artillery battalion.[57]

On 12-13 November 1989, a group of Hawiye officers and men belonging to the 4th Division at Galkayo, in Mudug, mutinied. General Barre's son, Maslah, lead a force of Marehan clansmen to suppress the mutiny. Punishment was meted out to local Hawiye villages.[58] In mid-November 1989, rebel forces briefly captured Galkayo. They reportedly seized significant quantities of military equipment at the 4th Division Headquarters, including tanks, 30 mobile anti-aircraft guns and rocket launchers. However, the rebels were unable to take most of this equipment so they incinerated it. Government forces thereafter launched massive reprisals against civilians residing in the regions corresponding with the 21st, 54th, 60th and 77th military sectors. The impacted towns and villages included Gowlalo, Dagaari, Sadle-Higlo, Bandiir Adley, Galinsor, Wargalo, Do'ol, Halimo, Go'ondalay and Galkayo.[59]

By mid 1990, USC insurgents had captured most of the towns and villages surrounding Mogadishu (Adam 1998, 389). On 8 November 1990, USC forces launched attack on the government garrison at Bulo-Burte, killing the commander. From 30 December 1990, there was a major upsurge in local violence in Mogadishu, and continuous fighting between government troops and USC insurgents. The next four weeks were marked by increasing rebel gains. On 27 January 1991, Siad Barre fled the capital for Kismayo.[60]

The various rebel movements eventually succeeded in ousting the government altogether in the ensuing civil war that reached a climax in January 1991. Amid the chaos that surrounded Barre's flight from the capital, what remained of the Somali armed forces dissolved. In 1992, the UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo via United Nations Security Council Resolution 733 in order to stop the flow of weapons to feuding militia groups.[61] Much equipment was left in situ, deteriorating, and was sometimes discovered and photographed by intervention forces in the early 1990s.

Transitional period

It was reported on 7 November 2001, that Transitional National Government (TNG) military forces had seized control of Marka in Lower Shabelle.[62] From 2002, Ismail Qasim Naji served as the TNG military chief.[63] He was given the rank of Major General. The TNG's new army, made up of 90 women and 2,010 men, was equipped on 21 March 2002 with guns and armed wagons surrendered to the TNG by private parties in exchange for money, according to TNG officials. TNG president Abdulkassim Salat Hassan instructed the recruits to use the weaponry to "pacify Mogadishu and other parts of Somalia by fighting bandits, anarchists and all forces that operate for survival outside the law." But the TNG controlled only one part of Mogadishu; rival warlords controlled the remainder.[64] Some TNG weapons were stolen and looted in late 2002.[65] During this time, the TNG was opposed militarily and politically by the rival Somalia Reconciliation and Restoration Council (SRRC).

Eventually the leadership of the SRRC and the TNG were reconciled, and the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) was formed in 2004 by Somali politicians in Nairobi. Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed from Puntland was elected as President.[66][67] The TFG later moved its temporary headquarters to Baidoa.[66] President Yusuf requested that the African Union deploy military forces in Somalia. However, as the AU lacked the resources to do so, Yusuf brought in his own militia from Puntland. Along with the U.S. funding the ARPCT coalition, this alarmed many in south-central Somalia, and recruits flocked to the ascendant Islamic Courts Union (ICU).[68]

A battle for Mogadishu followed in the first half of 2006 in which the ARPCT confronted the ICU.[69] However, with local support, the ICU captured the city in June of the year. It then expanded its area of control in south-central Somalia over the following months, assisted militarily by Eritrea.[68] In an effort at reconciliation, TFG and ICU representatives held several rounds of talks in Khartoum under the auspices of the Arab League. The meetings ended unsuccessfully due to uncompromising positions retained by both parties.[66] Hardline Islamists subsequently gained power within the ICU, prompting fears of a Talibanization of the movement.[70]

In December 2006, Ethiopian troops entered Somalia to assist the TFG against the advancing Islamic Courts Union,[71] initially winning the Battle of Baidoa. On 28 December 2006, the allied forces recaptured the capital from the ICU.[72] The offensive helped the TFG solidify its rule.[69] Ethiopian and TFG forces forced the ICU from Ras Kamboni between 7–12 January 2007. They were assisted by at least two U.S. air strikes.[73] On 8 January 2007, for the first time since taking office, President Ahmed entered Mogadishu from Baidoa as the TFG moved its base to the national capital.[74] President Ahmed brought his Puntland army chief with him, and Abdullahi Ali Omar became Somali chief of army on 10 February 2007.[75]

On 20 January 2007, with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1744, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) was formally authorised, making it possible to securely assure the government's presence in Mogadishu.[76] Seven hundred Ugandan troops, earmarked for AMISOM, were landed at Mogadishu airport on 7–8 March 2007.[77]

In Mogadishu, Hawiye residents resented the Islamic Courts Union's defeat.[78] They distrusted the TFG, which was at the time dominated by individuals from the Darod clan, believing that it was dedicated to the advancement of Darod interests in lieu of the Hawiye. Additionally, they feared reprisals for massacres committed in 1991 in Mogadishu by Hawiye militants against Darod civilians, and were dismayed by Ethiopian involvement.[79] Critics of the TFG likewise charged that its federalist platform was part of a plot by the Ethiopian government to keep Somalia weak and divided.[80] During its first few months in the capital, the TFG was initially restricted to key strategic points, with the large northwestern and western suburbs controlled by Hawiye rebels.[81] In March 2007, President Ahmed announced plans to forcibly disarm militias in the city.[79] According to the ISA, a coalition of local insurgents led by Al-Shabaab subsequently launched a wave of attacks against the TFG and Ethiopian troops.[82] The allied forces in return mounted a heavy-handed response.[83]

All of the warring parties were responsible for widespread violations of the laws of war, as civilians were caught in the ensuing crossfire. Insurgents reportedly deployed militants and established strongholds in heavily populated neighborhoods, launched mortar rounds from residential areas, and targeted public and private individuals for assassination and violence.[82] TFG forces alleged to have failed to efficaciously warn civilians in combat zones, impeded relief efforts, plundered property, in some instances engaged in murder and violence, and mistreated detainees during mass arrests.[82][84] According to HRW, the implicated TFG forces included military, police and intelligence personnel, as well as the private guards of senior TFG officials. Victims were often unable to identify TFG personnel, and confused militiamen aligned with TFG officials with TFG police officers and other state security personnel.[84]

In May 2007, U.S. diplomats spoke with the TFG's Ambassador to Ethiopia. Among the topics of conversation were Somali security forces, and Ambassador Abdulkarim Farah said that the TFG had trained nearly 7,000 militia in Baledogle who were now patrolling throughout Somalia, from Kismayo to Puntland.[85] Another 3,500 militia were undergoing training. Farah said that on 18 May he planned to his hometown of Beledweyne to establish a militia training camp there, at the instruction of President Yusuf. Farah estimated that approximately 60 per cent of the militia were Darod, 30 per cent were Hawiye, and the remaining 10 per cent were from other clans; the majority of security forces in Mogadishu were Darod. He said that the TFG had not sought to exclude Darod from the militia, and attributed the imbalance to Hawiye having primarily supported the Council of Islamic Courts (CIC).

In December 2008, the International Crisis Group reported:[86]

Yusuf has built a largely subservient and loyal apparatus by putting his fellow Majerteen clansmen in strategic positions. The National Security Agency (NSA) under General Mohamed Warsame ("Darwish") and the so-called "Majerteen militia" units in the TFG army operate in parallel and often above other security agencies. Their exact number is hard to ascertain, but estimates suggest about 2,000.[87] They are well catered for, well armed and often carry out counter-insurgency operations with little or no coordination with other security agencies. In the short term, this strategy may appear effective for the president, who can unilaterally employ the force essentially as he pleases. However, it undermines morale in the security services and is a cause of their high desertion rates.

Much of the problem building armed forces was the lack of functioning TFG government institutions:[88]

Beyond the endemic internal power struggles, the TFG has faced far more serious problems in establishing its authority and rebuilding the structures of governance. Its writ has never extended much beyond Baidoa. Its control of Mogadishu is ever more contested, and it is largely under siege in the rest of the country. There are no properly functioning government institutions.

Also in December 2008, Human Rights Watch described the Somali National Army as the 'TFG's largely theoretical professional military force.' It said that 'where trained TFG military forces appear, 'they were identified by their victims as Ethiopian-trained forces, often acting in concert with ENDF (Ethiopian National Defense Force) forces or under the command of ENDF officers.'[89] HRW also said that 'Human Rights Watch's own research has uncovered a pattern of violent abuses by TFG forces including widespread acts of murder, rape, looting, assault, arbitrary arrest and detention, and torture. Those responsible include police, military, and intelligence personnel as well as the personal militias of high-ranking TFG officials.'[89]

HRW went on to say: 'The TFG has deployed a confusing array of security forces and armed militias to act on its behalf. Victims of the widespread abuses in which these forces have been implicated often have trouble identifying whether their attackers were TFG police officers, other TFG security personnel, or militias linked to TFG officials. Furthermore, formal command-and-control structures are to a large degree illusory. TFG security forces often wear multiple hats, acting on orders from their formal superiors one day, as clan militias another day, and as autonomous self-interested armed groups the next.'[89]

In April 2009, donors at a UN-sponsored conference pledged over $250 million to help improve security. The funds were earmarked for AMISOM and supporting Somalia's security, including the build-up of a security force of 6,000 members as well as an augmented police force of 10,000 men.[90] In June 2009, the Somali military received 40 tonnes worth of arms and ammunition from the U.S. government to assist it in combating the insurgency.[91]

In November 2010, a new technocratic government was elected to office. In its first 50 days in office, the new administration completed its first monthly payment of stipends to government soldiers.[92] It was the first of many Somali administrations to announce plans for a full biometric register for the security forces. While it aimed to complete the biometric register within four months, little further was reported. By August 2011, AMISOM and Somali forces had managed to capture all of Mogadishu from Al-Shabaab.[93]

In October 2011, following a weekend preparatory meeting between Somali and Kenyan military officials in the town of Dhobley,[94] the Kenya Defence Forces launched an attack across the border against Al-Shabaab, aiming for Kismayo.[95][96] In early June 2012, Kenyan troops were formally integrated into AMISOM.[97]

In January 2012, Somali government forces and their AMISOM allies launched offensives on Al-Shabaab's last foothold on the northern outskirts of Mogadishu.[98] The following month, Somali forces fighting alongside AMISOM seized Baidoa from the insurgent group.[99] By June 2012, the allied forces had also captured El Bur,[100] Afgooye,[101] and Balad.[102] Progress by the Kenya Army from the border towards Kismayo was slow, but Afmadow was also reported captured on 1 June 2012.[103]

Creation of Federal Government

The Federal Government of Somalia was established in August/September 2012. On 6 March 2013, United Nations Security Council Resolution 2093 was passed. The resolution lifted the purchase ban on light weapons for a provisional period of one year, but retained restrictions on the procurement of heavy arms such as surface-to-air missiles, howitzers and cannons.[61]

On 13 March 2013, Dahir Adan Elmi was appointed Chief of Army at a transfer ceremony in Mogadishu, where he replaced Abdulkadir Sheikh Dini. Abdirisaq Khalif Hussein was appointed as Elmi's new Deputy Chief of Army.[104]

In August 2013, Federal Government of Somalia officials and Jubaland regional representatives signed an agreement in Addis Ababa brokered by the Government of Ethiopia, which said that all Jubaland security elements will be integrated into the Somali National Army. The Juba Interim Administration would control the regional police.[105]

In November 2013, the United Nations Support Office for AMISOM (UNSOA) was directed to support the SNA across South Central Somalia. They were to better supply a force of 10,900 Somalis to fight al-Shabaab forces.[106] The SNA force would initially be trained by the AMISOM contingents. On the passing of specific UN requirements,[107] designated SNA battalions would then participate in joint operations with AMISOM. UNSOA's support during the period comprised food supplements, shelter, fuel, water and medical support.[108]

In early March 2014, Somali security forces and AMISOM troops launched another operation against Al-Shabaab in southern Somalia.[109] According to Prime Minister Abdiweli Sheikh Ahmed, the government subsequently launched stabilization efforts in the newly liberated areas, which included Rab Dhuure, Hudur, Wajid and Burdhubo. However, there were continuing concerns that not enough was being done to revitalise and secure the newly liberated areas. By 26 March, the allied forces had liberated ten towns within the month, including Qoryoley and El Buur.[110][111] UN Special Representative for Somalia Nicholas Kay described the military advance as the most significant and geographically extensive offensive since AU troops began operations in 2007.[112]

In August 2014, the Somali government launched Operation Indian Ocean.[113] On 1 September 2014, a U.S. drone strike carried out as part of the broader mission killed Al-Shabaab leader Moktar Ali Zubeyr.[114] U.S. authorities hailed the raid as a major symbolic and operational loss for Al-Shabaab, and the Somali government offered a 45-day amnesty to all moderate members of the militant group.[115]

In October 2014, Federal Government officials signed an agreement in Garowe with Puntland, which said that the Federal and Puntland authorities will work to form an integrated national army.[116] In April 2015, another bilateral treaty stipulated that Puntland would contribute 3,000 troops to the Somali National Army.[117] In May 2015, President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud and the heads of the Puntland, Jubaland and Interim South West Administrations signed a seven-point agreement in Garowe authorizing the immediate deployment of 3,000 troops from Puntland for the Somali National Army.[118] The leaders also agreed to integrate soldiers from the other regional states into the SNA.[119]

In 2016 The Economist reported that the SNA did not exist as a cohesive force due to high rates of desertions and many soldiers being primarily loyal to clan leaders rather than the government.[120]

Somali National Army from 2008

Training and facilities

.jpg)

In November 2009, the European Union announced its intention to train two Somali battalions (around 2,000 troops), which would complement other training missions and bring the total number of better-trained Somali soldiers to 6,000.[121] The two battalions were expected to be ready by August 2011.[122] In April 2011, 1,000 recruits completed training in Uganda as a part of the agreement with the EU.[123]

Powerful vested interests and corrupt commanders were, as of February 2011, the largest obstacle to reforming the army. Some newly delivered weaponry was sold by officers. The International Crisis Group also said that AMISOM's efforts at assisting in formalizing the military's structure and providing training to the estimated 8,000 SNA soldiers were problematic. Resistance continued to the establishment of an effective chain of command, logical military formations and a credible troop roster. Although General Mohamed Gelle Kahiye, the respected former army chief, attempted to instill reforms, he was marginalized and eventually dismissed.[124]

In August 2011, as part of the European Union Training Mission Somalia (EUTM Somalia), 900 Somali soldiers graduated from the Bihanga Military Training School in the Ibanda District of Uganda.[125][126] 150 personnel from the EU took part in the training process, which trained around 2,000 Somali troops per year.[126] In May 2012, 603 Somali army personnel completed training at the facility. They were the third batch of Somali nationals to be trained there under the auspices of EUTM Somalia.[127] In total, the EU mission had trained 3,600 Somali soldiers, before permanently transferring all of its advisory, mentoring and training activities to Mogadishu in December 2013.[128]

In September 2011, President Sharif Sheikh Ahmed laid down the foundation for a new military camp for the army in the Jazeera District of Mogadishu. The $3.2 million construction project was funded by the EU and was expected to take six months to complete.[129]

In June 2013, Egyptian engineers arrived to build new headquarters for the Somalia Ministry of Defence.[130]

In February 2014, EUTM Somalia began its first "Train the Trainers" programme at the Jazeera Training Camp in Mogadishu. 60 Somali National Army soldiers that had been previously trained by EUTM in Uganda would take part in a four-week refresher course on infantry techniques and procedures, including international humanitarian law and military ethics. The training would be conducted by 16 EU trainers. Following the course's completion, the Somali soldiers would be qualified as instructors to then train SNA recruits, with mentoring provided by EUTM Somalia personnel.[131] A team of EUTM Somalia advisors also started offering strategic advice to the Somali Ministry of Defence and General Staff. Additionally, capacity building, advice and specific mentoring with regard to security sector development and training are envisioned for 2014.[132]

In February 2014, Chief of Staff Brigadier General Dahir Adan Elmi announced that Somalia's Ministry of Defence began holding military training inside the country for the first time, with Somali instructors now teaching courses to units that joined the armed forces. He also indicated that SNA leaders had created new numbered units for the army, and that the soldiers were slated to have their respective name and unit placed on their uniform. Additionally, Elmi stated that the military had implemented a new biometric registration system, wherein each recently trained and armed soldier is photographed and fingerprinted.[133] By the end of 2014, 17,000 national army soldiers and police officers had registered for the new biometric remuneration system.[134] 13,829 SNA soldiers and 5,134 Somali Police Force officials were biometrically registered in the system as of May 2015.[135]

In July 2014, the governments of the United States and France announced that they would start providing training to the Somali National Army.[136] According to U.S. Defense Department officials, American military advisers are also stationed in Somalia.[137]

In September 2014, 20 Somali federal soldiers began training courses in Djibouti, which were organized by the government of Djibouti.[138]

In September 2014, a Somali government delegation led by Prime Minister Abdiweli Sheikh Ahmed attended an international conference in London hosted by the British government, which centered on rebuilding the Somali National Army and strengthening the security sector in Somalia. Ahmed presented to the participants his administration's plan for the development of Somalia's military, as well as fiscal planning, human rights protection, arms embargo compliance, and ways to integrate regional militias. The summit also aimed to increase financial support for the Somali military. British Prime Minister David Cameron in turn indicated that the meeting sought to outline a long-term security plan to strengthen Somalia's army, police and judiciary.[139]

In March 2015, the Federal Cabinet agreed to establish a new commission tasked with overseeing the nationalization and integration of security forces in the country.[140] In April 2015, the Commission on Regional Militia Integration presented its plan for the formal integration of regional forces, with UNSOM providing support and strategic advice.[135]

In April 2015, the federal Ministry of Defence launched its new Guulwade Plan (Victory Plan), which provides a roadmap for long-term development of the military. It was formulated with technical support from UNSOM. The framework stipulates that international partners are slated to provide capacity-building as well as assistance for joint operations to 10,900 Somali national army troops, with these units drawn from various regions in the country.[135]

As of April 2015, UNSOM coordinates international security sector assistance for the SNA in accordance with the Somali federal government's priority areas. It also provides advice on recruitment of female officers, strictures on age appropriate military personnel, legal frameworks vis-a-vis the defence institutions, and a development strategy for the Ministry of Defence. Beginning in the month, the US government also funded the payment of 9,495 army allowances.[135]

In May 2015, President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud officially opened a new military training camp in Mogadishu. Construction of the center began in 2014 in conjunction with the government of the United Arab Emirates. Situated in the Hodan district, it is one of several new military academies in the country.[141]

As of May 2015, the federal government in conjunction with UNSOM was working toward establishing a comprehensive, international standards and obligations-compliant ammunition and weapons management system. To this end, capacity-building for the physical management of arms and bookkeeping was being developed, and new storage facilities and armouries for weapons and explosives were being constructed.[135]

Strength and units

In August 2011, the TFG announced the creation of a new Special Force. Consisting of 300 trained soldiers, the unit was initially mandated with protecting relief shipments and distribution centers in Mogadishu. Besides helping to stabilize the city, the protection force is also tasked with combating banditry and other vices.[142]

In March 2013 there were six trained brigades around Mogadishu, two of which were deployed at the time. Each brigade includes three to six battalions of around 1000 soldiers apiece, or 18,000 to 36,000 troops in total. Of these, an estimated 6,000 to 12,000 soldiers are currently in service.[143]

The six SNA brigades around Mogadishu were as of July 2013 largely composed of officers from various Hawiye sub-clans, with some Marehan-Darod and minorities also present in certain units. Of the brigades, five primarily consisted of Abgaal, Murosade and Hawadle soldiers. In February 2013 the 2nd Brigade was under the command of Brigadier General Abdullahi Osman Agey. The 3rd Brigade over the same period comprised 840 fighters, most of whom belong to the Hawiye-Habar Gidir/Ayr clan. The unit was around 30% to 50% smaller in size than the other five brigades that are garrisoned in the larger Banaadir region. Led by General Mohamed Roble Jimale 'Gobale', it occupied an area outside of Mogadishu and Merka and along the Afgoye corridor. The Monitoring Group reported that many 3rd Brigade fighters had been drawn from around 300-strong militias controlled by Yusuf Mohamed Siyaad 'Indha Adde', a close associate of Jimale and the former Eritrean-backed chief of defence for the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia-Asmara. However, Siyaad was by then no longer part of the SNA's official military structures.[144]

As of May–June 2014, the army reportedly consists of an estimated 20,000 soldiers. Of these, the majority are men, with around 1,500 female SNA officials.[145]

The Fifth Brigade was identified in reporting about a New Zealand UN advisor.[146] Later, on 9 June 2014, Garowe Online referred to the Fifth and Sixth Brigades of the SNA, in Lower Shabelle.[147] The 5th and 6th Brigades have fought against Al-Shabaab including in Mogadishu and Afgoye. With a post-training drop-out rate of around 10%, the vast majority of the EUTM-trained soldiers have continued to serve in the Somalia national security forces after their initial period of training abroad. Overall, the Somali armed forces' combat capability has strengthened due in part to having both more combat experience and international support, including training, leadership and planning facilitation.[148]

In February 2014, the Federal Government concluded a six-month training course for the first Commandos, Danab ("Lightning"), since 1991.[149] Training had been carried out by Bancroft Global Development, a U.S. private military contractor, paid by AMISOM which is then reimbursed by the U.S. State Department. The aim was to create a mixed-clan unit. The Commandos will be headquartered at the former Balli Dogle air base (Walaweyn District, Lower Shabelle).[149] The training of the first Danab unit had begun in October 2013, and included 150 soldiers. As of July 2014, training of the second unit was underway. According to General Elmi, the special training is geared toward both urban and rural environments, and is aimed at preparing the soldiers for guerrilla warfare and all other types of modern military operations. Elmi said that a total of 570 Commandos are expected to have completed training by U.S. security personnel by the end of 2014.[137]

Agreements

Somalia has signed military cooperation agreements with Turkey in May 2010,[150] February 2014,[151] and January 2015.[152]

In February 2012, Somali Prime Minister Abdiweli Mohamed Ali and Italian Defence Minister Gianpaolo Di Paola agreed that Italy would assist the Somali military as part of the National Security and Stabilization Plan (NSSP),[153] an initiative designed to strengthen and professionalize the national security forces.[154] The agreement would include training soldiers and rebuilding the Somali army.[153] In November 2014, the Federal Parliament approved a new defense and cooperation treaty with Italy, which the Ministry of Defence had signed earlier in the year. The agreement includes training and equipping of the army by Italy.[155]

In November 2014, Somalia signed a military cooperation agreement with the United Arab Emirates.[156]

Turkey signed an agreement with Somalia in early 2016, to open a military base in Somalia, at which Turkish Armed Forces officers will train Somali soldiers and troops from other African countries to fight against Al-Shabaab. The base was established in the capital Mogadishu. Over 1,500 Somali troops were to be trained by 200 Turkish personnel. The Turkish army is also planning to build a military school in Somalia to train officers.[157]

Army equipment

Army equipment, 1981

The following were the Somali National Army's major weapons in 1981:[6]

Army equipment, 1989

Previous arms acquisitions included the following equipment, much of which was unservicable ca. June 1989:[55] 293 main battle tanks (30 Centurion from Kuwait[158] 123 M47 Patton, 30 T-34, 110 T-54/55 from various sources). Other armoured fighting vehicles included 10 M41 Walker Bulldog light tanks, 30 BRDM-2 and 15 Panhard AML-90 armored cars (formerly owned by Saudi Arabia). The IISS estimated in 1989 that there were 474 armoured personnel carriers, including 64 BTR-40/BTR-50/BTR-60, 100 BTR-152 wheeled armored personnel carriers, 310 Fiat 6614 and 6616s, and that BMR-600s had been reported. The IISS estimated that there were 210 towed artillery pieces (8 M-1944 100 mm, 100 M-56 105 mm, 84 M-1938 122 mm, and 18 M198 155 mm towed howitzers). Other equipment reported by the IISS included 82 mm and 120 mm mortars, 100 Milan and BGM-71 TOW anti-tank guided missiles, rocket launchers, recoilless rifles, and a variety of Soviet air defence guns of 20 mm, 23 mm, 37 mm, 40 mm, 57 mm, and 100 mm calibre.

Equipment donations, 2012–2013

In May 2012, over thirty-three vehicles were donated by the U.S. government to the SNA. The vehicles include 16 Magirus Trucks, 4 Hilux Pickups, 6 Land Cruiser Pickups, 1 Water Tanker, and 6 Water Trailers.[159] On 9 April 2013, the U.S. government approved the provision of defense articles and services by the American authorities to the Somali Federal Government.[160] It handed over 15 vehicles to the new Commandos in March 2014.[161]

In April 2013, Djibouti presented the SNA with 15 armoured military vehicles. The equipment was part of a larger consignment of 25 military trucks and 25 armoured military vehicles.[162]

The same month, the Italian government handed over 54 armored and personnel carrier vehicles to the army at a ceremony in Mogadishu.[163]

As of April 2015, the Ministry of Defence's Guulwade Plan identifies the equipment and weaponry requirements of the army.[135]

Army Weaponry And Equipment c. 2017

Somali Air Force

The Somali Air Force (SAF) was originally named the Somali Air Corps (SAC), and was established with Italian aid in the early 1960s. It emerged from the Italian "Corpo di Sicurezza della Somalia" that existed between 1950 and 1960, during the trusteeship period just prior to independence. The SAF's original equipment included eight North American P-51D Mustang and Douglas C-47s which remained in service until 1968. The air force operated most of its aircraft from bases near Mogadishu, Hargeisa and Galkayo. An air defence force equipped with Soviet surface-to-air missiles and anti-aircraft guns was in existence by 1991–92.[173]

By January 1991 the air force was in ruins.[9] In 2012, Italy offered to help rebuild the air force.

According to CQ Press' Worldwide Government Directory with Intergovernmental Organizations, Somalia's reconstituted air force as of 2013 is led by Maj. Gen. Nur Ilmi Adawe.[1]

Somali Navy

The Somali Navy was formed after independence in 1960. Prior to 1991, it participated in several joint exercises with the United States, Great Britain and Canada. It disintegrated during the beginning of the civil war in Somalia, from the late 1980s.[11] In the 2000s (decade), the central government began the process of re-establishing the Somali Navy.[174]

On 30 June 2012, the United Arab Emirates announced a contribution of $1 million toward enhancing Somalia's naval security. Boats, equipment and communication gear necessary for the rebuilding of the coast guard would be bought. A central operations naval command was also planned to be set up in Mogadishu.[175]

Leadership

Minister of Defence

| Name | Tenure | Affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Abdirashid Abdullahi Mohamed | 27 March 2017 – present | Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) |

| Abdulkadir Sheikh Dini | 27 January 2015 – 27 March 2017 | Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) |

| Mohamed Sheikh Hassan | 17 January 2014 – 27 January 2015 | Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) |

| Abdihakim Mohamoud Haji-Faqi | 4 November 2012 – 17 January 2014 | Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) |

| Hussein Arab Isse | 20 July 2011 – 4 November 2012 | Transitional Federal Government (TFG) |

| Abdihakim Mohamoud Haji-Faqi | 12 November 2010 – 20 July 2011 | Transitional Federal Government (TFG) |

| Mohamed Abdi Mohamed | 21 February 2009 – 12 November 2010 | Transitional Federal Government (TFG) |

| Aden Abdullahi Nur | 1986–1988 | Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP) |

| Muhammad Ali Samatar | 1980–1986 | Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP) |

Chief of Army

| Name | Took command | Left command |

|---|---|---|

| Maj. Gen Ismail Qasim Naji | 14 April 2005[176] | 10 February 2007[75] |

| Maj. Gen Abdullahi Ali Omar | 10 February 2007[75] | 21 July 2007[177] |

| Brig. Gen Salah Hassan Jama | 21 July 2007[177] | 11 June 2008[178] |

| Maj. Gen Said Dheere Mohamed | 11 June 2008[178] | 15 May 2009[179] |

| Maj. Gen Yusuf Osman Dhumal | 15 May 2009[179] | 10 December 2009[180] |

| Brig. Gen Mohamed Gelle Kahiye | 6 December 2009[180] | 18 September 2010[181] |

| Brig. Gen Ahmed Jimale Gedi | 18 September 2010 | 28 March 2011 |

| Maj. Gen Abdulkadir Sheikh Dini | 28 March 2011[182] | 13 March 2013[183] |

| Brig. Gen Dahir Adan Elmi | 13 March 2013[183] | 3 September 2015 |

| Maj. Gen Mohamed Adam Ahmed | 24 September 2015 | 5 April 2017[183] |

| Brig. Gen Ahmed Mohamed Jimale | 5 April 2017 | Current[184] |

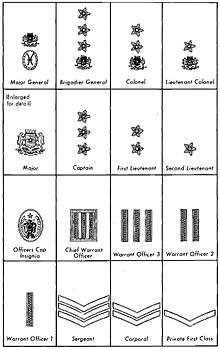

Military ranks

In July 2014, General Dahir Adan Elmi announced the completion of a review of the Somali National Army ranks. The SNA in conjunction with the Ministry of Defense is also slated to standardize the martial ranking system and eliminate any unauthorized promotions as part of a broader reform.[185]

As of 1977, Somalia's army ranks were as follows:[6]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Martino, John (2013). Worldwide Government Directory with Intergovernmental Organizations 2013. CQ Press. p. 1462. ISBN 1-4522-9937-4.

- ↑ "Somalia's president declares country a war zone, replaces military and chiefs – Toronto Star". Toronto Star. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2018/4/23/somali-military-faction-raid-uae-backed-army-camp

- ↑ "The Federal Republic of Somalia – Provisional Constitution" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ↑ "The Federal Republic of Somalia – Provisional Constitution". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2013. Chapter 14, Article 126(3).

- 1 2 3 4 "Somalia: A Country Study – Chapter 5: National Security" (PDF). Library of Congress. c. 1981. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012.

- ↑ See discussion in Abdullah A. Mohamoud, State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa : the case of Somalia (1960–2001). West Lafayette, Ind. : Purdue University Press, c2006

- ↑ Daniel Compagnon, 'Political decay in Somalia: From Personal Rule to Warlordism Archived 9 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine.,' Refuge, Vol 12, No. 5, November–December 1992, 9.

- 1 2 Nina J. Fitzgerald, Somalia: issues, history, and bibliography, (Nova Publishers: 2002), p.19.

- ↑ "SOMALIA PM Said 'Cabinet will work tirelessly for the people of Somalia'". Midnimo. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Library of Congress Country Study, Somalia, The Warrior Tradition and Development of a Modern Army Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine., research complete May 1992.

- ↑ Saheed A. Adejumobi, The History of Ethiopia, (Greenwood Press: 2006), p.178

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, inc, Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2005), p.163

- ↑ David D. Laitin and Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State (Boulder: Westview Press, 1987).

- ↑ Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare: Renaissance to revolution, 1492–1792 By Jeremy Black pg 9

- ↑ W. Mitchell. Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Whitehall Yard, Volume 57, Issue 2. p. 997.

- ↑ William James Makin. War Over Ethiopia. p. 227.

- ↑ "Puntland Forces mark 50th anniversary of Somali Armed". Garowe Online. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p. 835

- ↑ "The dawn of the Somali nation-state in 1960". Buluugleey.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ↑ A transcript of a Reuters report of 26 June 1960 says that, during the independence ceremony for Somaliland "..Nearly 1,000 British-trained Somaliland Scouts were then handed over to the Prime Minister by Brigadier O. G. Brooks, the Colonel Commandant." http://www.slnnews.com/2015/06/somaliland-independence-26th-june-1960-the-world-press/ {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160426094602/http://www.slnnews.com/2015/06/somaliland-independence-26th-june-1960-the-world-press/ |date=26 April 2016 }}

- 1 2 Library of Congress Country Study, Somalia, Manpower, Training, and Conditions of Service Archived 9 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. (Thomas Ofcansky), research complete May 1992.

- ↑ Michael Walls and Steve Kibble, "Beyond Polarity: Negotiating a Hybrid State in Somaliland", Africa Spectrum, 2010.

- ↑ Library of Congress Country Studies Somalia, Problems of National Integration Archived 11 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine., Library of Congress, research completed May 1992.

- ↑ Adam 1998, 382.

- 1 2 Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "Coup d'Etat", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, retrieved 21 October 2009

- ↑ Mohamed Haji (Ingiriis), http://www.hiiraan.com/op4/2010/dec/17095/somalia_from_finest_to_failed_state_part_iii.aspx Archived 30 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine.. See also Abdirashid A. Ismail, Somali State Failure, Players, Incentives AND INSTITUTIONS, Helsinki.

- ↑ Kaplan et al, Area Handbook for Somalia, Second Edition, 1977, p.315

- ↑ IISS Military Balance 1976–77, p.44

- ↑ Abdullahi Yusuf Irro once commanded the 60th.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- 1 2 Ahmed III, Abdul. "Brothers in Arms Part I" (PDF). WardheerNews. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ Lewis, I.M.; The Royal African Society (October 1989). "The Ogaden and the Fragility of Somali Segmentary Nationalism". African Affairs. 88 (353). doi:10.2307/723037. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ↑ Gebru Tareke, "The Ethiopia-Somalia War", p. 638.

- ↑ Urban, Mark (1983). "Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978". The RUSI Journal. 128 (2): 42–46. doi:10.1080/03071848308523524.

- 1 2 Gebru Tareke, "From Lash to Red Star: The Pitfalls of Counter-Insurgency in Ethiopia, 1980–82", Journal of Modern African Studies Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., 40 (2002), p. 471

- ↑ Lockyer, Adam. "Opposing Foreign Intervention's Impact on the Course of Civil Wars: The Ethiopian-Ogaden Civil War, 1976–1980" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ IRIN Special Report on Central Somalia Archived 4 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine., 13 May 1999.

- ↑ ARR: Arab report and record, (Economic Features, ltd.: 1978), p.602.

- ↑ New People Media Centre, New people, Issues 94–105, (New People Media Centre: Comboni Missionaries, 2005).

- ↑ Nina J. Fitzgerald, Somalia: issues, history, and bibliography, (Nova Publishers: 2002), p.25.

- ↑ Ciisa-Salwe, Cabdisalaam M. (1996). The collapse of the Somali state: the impact of the colonial legacy. HAAN Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 1-874209-91-X.

- ↑ Hutchful, Eboe; Bathily, Abdoulaye (1998). "Chapter 10: Somalia: Personal Rule, Military Rule and Militarism". The Military and Militarism in Africa. CODESRIA. p. 373. ISBN 2-86978-069-9. Hussein M. Adam, the chapter author, cites interviews with Colonel Abdullahi Kahim, Toronto, 1 and 3 August 1992. Kahim served as director of finance and administration in the Ministry of Defence from 1977–87.

- ↑ Compagnon, 1992, 9.

- ↑ Compagnon, 1992, 9, see also 'Somalia: Military Politics,' Africa Confidential, 27, No. 22, 26 October 1986, 1–2.

- ↑ Hussain M. Adam, op. cit., 1998, 383, citing interview with Colonel Farah.

- ↑ Daniel Compagnon, 'Political decay in Somalia: From Personal Rule to Warlordism,' Refuge, Vol 12, No. 5, November–December 1992, 9, cited in Mohamoud, 2006, p.127

- ↑ 'Somalia: Military Politics,' Africa Confidential, 27, No. 22, 26 October 1986, 1–2.

- ↑ Defense Intelligence Agency, 'Military Intelligence Summary, Vol IV, Part III, Africa South of the Sahara', November 1987, 12

- ↑ Walter S. Clarke, Background Information for Operation Restore Hope, Strategic Studies Institute, p. 27.

- ↑ "Somalia – Government". Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ Daniel Compagnon, 'Political decay in Somalia: From Personal Rule to Warlordism,' Refuge, Vol 12, No. 5, November–December 1992, 9

- ↑ United States Marine Corps, Restoring Hope in Somalia with the Unified Task Force Archived 30 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine., 63.

- ↑ "Bring-Backs From Somalia Deployment – SPOILS OF WAR". usmilitariaforum.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 IISS Military Balance 1989–90, Brassey's for the IISS, 1989, 113.

- ↑ "History and Development of the Armed Forces". loc.gov. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Helen Chapin Metz, Library of Congress Country Study, Somalia, Army Mission, Organization, and Strength, research complete May 1992.

- ↑ Clarke, Background Information, Strategic Studies Institute, 29.

- ↑ "Human Rights Watch" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Walter S. Clarke, Background Information for Restore Hope, Chronology, Strategic Studies Institute, 31-32.

- 1 2 "UN eases oldest arms embargo for Somalia". Australian Associated Press. 6 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ "Government military takes control of Marka". IRIN. 7 November 2001. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "The Lives of 18 American Soldiers Are Not Better Than Thousands of Somali Lives They Killed, Somalia's TNG Prime Minister Col. Hassan Abshir Farah says". Somalia Watch. 22 January 2002. Archived from the original on 3 January 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ↑ Dan Connell, Middle East Report, "War Clouds Over Somalia," 22 March 2002, at http://www.merip.org/mero/mero032202 Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "somalilandtimes.net". somalilandtimes.net. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Background and Political Developments". AMISOM. Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ Wezeman, Pieter D. "Arms flows and conflict in Somalia" (PDF). SIPRI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- 1 2 Interpeace, 'The search for peace: A history of mediation in Somalia since 1988 Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.,' Interpeace, May 2009, 60–61.

- 1 2 "Ethiopian Invasion of Somalia". Globalpolicy.org. 14 August 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ Ken Menkhaus, 'Local Security Systems in Somali East Africa Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.,' in Andersen/Moller/Stepputat (eds.), Fragile States and Insecure People,' Palgrave, 2007, 67.

- ↑ "Somalia". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ↑ "Profile: Somali's newly resigned President Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed". Xinhua News Agency. 29 December 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ↑ International Crisis Group, Somalia: To Move Beyond the Failed State, Africa Report N°147 – 23 December 2008, 26.

- ↑ Majtenyi, Cathy (8 January 2007). "Somali President in Capital for Consultations". VOA. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Somalia's army commander sacked as new ambassadors are appointed". Shabelle Media Network. 10 April 2007. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ Williams, Paul D. "Into the Mogadishu maelstrom: the African Union mission in Somalia." International Peacekeeping 16.4 (2009): 516.

- ↑ More Ugandan troops arrive in Mogadishu Archived 20 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Xinhua News Agency via People's Daily Online, 8 March 2007.

- ↑ "Power vacuum in Somalia as factions fight". Garowe Online. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- 1 2 McGregor, Andrew (26 April 2007). "The Leading Factions Behind the Somali Insurgency" (PDF). Terrorism Monitor. V (8): 1–4. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ Menkhaus, Ken. "Somalia: What Went Wrong?". The Rusi Journal. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ Cedric Barnes, and Harun Hassan, "The rise and fall of Mogadishu's Islamic Courts Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.." Journal of Eastern African Studies 1, no. 2 (2007), 158.

- 1 2 3 "Somalia comes full circle". ISA. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ Leggiere, Phil. "Somalia: The Next Challenge – Homeland Security Today". Center for American Progress. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- 1 2 ""So Much to Fear" – Human Rights Abuses by Transitional Federal Government Forces". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ↑ U.S. State Department (18 May 2007). "Somali Ambassador to Ethiopia Highlights Need for Power-Sharing with Hawiye (07ADDISABABA1507)". Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017 – via Wikileaks.

- ↑ International Crisis Group, 'Somalia: To move beyond the failed state,' Crisis Group Africa Report 147, 23 December 2008, 22.

- ↑ Crisis Group footnote is 'Crisis Group interviews, Mogadishu, Baidoa, April 2008.'

- ↑ International Crisis Group, 'Somalia: To move beyond the failed state,' Crisis Group Africa Report 147, 23 December 2008, 43.

- 1 2 3 Human Rights Abuses by Transitional Federal Government Forces Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. in 'So Much to Fear: War Crimes and Devastation in Somalia'

- ↑ "Removed: news agency feed article". The Guardian. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Reuters, US gives Somalia about 40 tons of arms, ammunition Archived 29 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Security Council Meeting on Somalia". Somaliweyn.org. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014.

- ↑ Independent Newspapers Online (10 August 2011). "Al-Shabaab 'dug in like rats'". Independent Online. South Africa.

- ↑ "Kenya launches offensive in Somalia". National Post. 16 October 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Somalia government supports Kenyan forces' mission". Standardmedia.co.ke. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Joint Communique – Operation Linda Nchi

- ↑ "Kenya: Defense Minister appointed as acting Internal Security Minister". Garowe Online. 19 June 2012. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ↑ "Al-Shabaab Evicted from Mogadishu". Somalia Report. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Ethiopian forces capture key Somali rebel stronghold". Reuters. 22 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ "Ethiopian troops seize main rebel town in central Somalia". modernghana.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Somali al-Shabab militant stronghold Afgoye 'captured'". BBC. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ "Somali forces capture rebel stronghold". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ "Somalia forces capture key al-Shabab town of Afmadow". BBC. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Shabelle.net, Somalia changes its top military commanders Archived 17 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Somalia: Jubaland gains recognition after intense bilateral talks in Ethiopia". Garowe Online. 28 August 2013. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "Support to Somali National Army (SNA)". UNSOA. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ "Resolution 2124". unscr.com. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ "Briefing to the UN Security Council by Ambassador Nicholas Kay, Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) for Somalia, 11 March 2014". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ "Somalia: Federal Govt, AMISOM troops clash with Al Shabaab". Garowe Online. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ "SOMALIA: The capture of Qoryooley is critical for the operations to liberate Barawe, Amisom head says". Raxanreeb. 22 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "SOMALIA: Elbur town falls for Somali Army and Amisom". Raxanreeb. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ↑ "Somalia, AU troops close in on key Shebab base". Agence France-Presse. 22 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "SOMALIA: President says Godane is dead, now is the chance for the members of al-Shabaab to embrace peace". Raxanreeb. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ "Pentagon Confirms Death of Somalia Terror Leader". Associated Press. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ "US confirms death of Somalia terror group leader". Associated Press. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ "Somalia: Puntland clinches deal with Federal Govt". Garowe Online. 14 October 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "Somalia: Puntland to contribute 3000 soldiers to Nat'l Army, another deal signed". Garowe Online. 12 April 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Somalia leaders call for Brussels pledges review at Garowe Conference". Garowe Online. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ "Communiqué on FGS and regional states meeting in Garowe". Goobjoog. 2 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ "Most-failed state". The Economist. 10 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters. "EU to provide 100 troops for training Somali force". Reuters. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ http://shabelle.net/article.php?id=6246

- ↑ "Sunatimes.com – East Africa Investigative Media". sunatimes.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ International Crisis Group, Somalia: The Transitional Government on Life Support Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine., Africa Report 170, 20 February 2011, p.16

- ↑ "900 newly trained Somali soldiers dispatched from Ugandan military school". Bar-Kulan. 2 September 2011.

- 1 2 "Special Forces in Mogadishu". Hiiraan Online. 7 September 2011.

- ↑ IRIN News, 14 May 2012, via Africa Research Bulletin-PSC, 1–31 May 2012, p.19287C.

- ↑ "EU military training programme launches in Somalia". Sabahi. 26 February 2014.

- ↑ "President Sharif Opens Military Camp in Capital". SomaliaReport. 16 September 2011.

- ↑ "Egypt to help re-build Somali Ministry of Defence". Sabahi. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ "EUTM Somalia starts its training activities in Mogadishu". EUTM Somalia. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ "Mission description". EUTM Somalia. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ "Somali National Army commander: Reviving army will take time". Sabahi. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ "Somalia's Year of Delivery". Goobjoog. 31 January 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Report of the Secretary – General on Somalia – S /2015/331". United Nations Security Council. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ↑ "US and France agrees to train Somali National army". Buraan News. 11 July 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- 1 2 Dan Joseph, Harun Maruf (31 July 2014). "US-Trained Somali Commandos Fight Al-Shabab". VOA. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ "Djibouti to train federal government forces". Goobjoog. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "An international conference in London on Somali security". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia. 19 September 2014. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "Somali Cabinet Ministers agree financial management committee to work temporarily". Goobjoog. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ "Somali president officially opens new military training centre in Mogadishu". Goobjoog. 12 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ Khalif, Abdulkadir (14 August 2011). "Somalia to set up aid protection force". Africa Review. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Kwayera, Juma (9 March 2013). "Hope alive in Somalia as UN partially lifts arms embargo". Standard Digital. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ↑ "Report S/2013/440 of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea pursuant to Security Council resolution 2060 (2012): Eritrea" (PDF). UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea. Retrieved 26 June 2014. , page 19, para. 50–51 & footnote 44.

- ↑ Guled, Abdi (30 May 2014). "Female soldiers increasingly joining military ranks in Somalia". The Daily Star. Associated Press. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ "Magazine". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Somalia: Rival Soldiers in Deadly Battle Again As PM Calls for Calm Archived 1 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine., http://allafrica.com/stories/201406100182.html/Garoweonline.com, 9 June 2014.

- ↑ Claes Nilsson, Johan Norberg. "European Union Training Mission Somalia – A Mission Assessment" (PDF). European Union Training Mission Somalia. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- 1 2 Mohyaddin, Shafi’i (8 February 2014). "Somalia trains its first commandos after the collapse of the central government". Hiiraan Online. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ "Turkey-Somalia military agreement approved". Today's Zaman. 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ "SOMALIA: Ministry of Defense signs an agreement of military support with Turkish Defense ministry". Raxanreeb. 28 February 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ "Press Release: Erdogan's Somalia Visit". Goobjoog. 25 January 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- 1 2 "PM meets Italian Defence minister, IFAD director and addressed Rome 3 students". Laanta. 2 February 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Press Release: AMISOM offers IHL training to senior officials of the Somali National Forces". AMISOM. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "SOMALIA: Parliament approves Somalia's military treaty with Italy". Raxanreeb. 4 November 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "UAE, Somalia sign military cooperation agreement". Kuwait News Agency. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ "Arms Trade Register". SIPRI. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ "PRESS RELEASE: AMISOM hands over military vehicles to the Somali National Army". AMISOM. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ "U.S. eases arms restrictions for Somalia". United Press International. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "SOMALIA: U.S donates military vehicles to newly trained Somali Commandos". Raxanreeb. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ↑ "Djibouti donates armoured vehicles to Somalia". Sabahi. 5 April 2013. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Italy Hands over Military Consignment to Somali Government". Goobjoog. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Military Balance 2017

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Jones, Richard D. Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane's Information Group; 35 edition (27 January 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

- 1 2 AfricaNews. "Several soldiers killed in al Shabaab attack on Somali army base – Africanews". africanews.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Daawo Sawirada: Qaabka ay Ciidamada Puntland ula wareegen Qandala". caasimada.net. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Salaami CALİ (29 April 2016). "somali military power 2016". Retrieved 4 April 2018 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Charbonneau, Louis. "Exclusive: Somalia army weapons sold on open market – U.N. monitors". Reuters. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ https://www.armyrecognition.com/images/stories/africa/somalia/ranks_uniforms/uniforms/pictures/Somalia_Somali_army_soldiers_military_combat_field_uniforms_002.jpg

- ↑ "Somali daily News – Meydadka Askar Itoobiyaan ah oo lagu soo bandhigay Gobolka Galgaduud+SAWIRO". shinganinews.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Turkish Firms Receive Orders to Manufacture 45000 Locally-made MPT-76 Rifles". defenseworld.net. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Somalia, A Country Study, 1992/3, 205.

- ↑ "Somalia to Make Task Marine Forces to Secure Its Coast". Shabelle Media Network. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ "UAE committed to contribute US$1 million to support Somali naval security capabilities, says Gargash". UAE Interact. 30 June 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Somali cabinet fills key posts". Al Jazeera. 14 April 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- 1 2 "Peaceful day for Somalia reconciliation conference" Archived 11 April 2013 at Archive.is garoweonline.com

- 1 2 "Somalia's Interim President Appoints New Chief of Staff for the Armed Forces" Archived 4 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. hiiraan.com

- 1 2 "Somali president names new military chief amid insurgent push" topnews.in

- 1 2 "Somalia fires heads of police force and military" Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. reuters.com

- ↑ "Somali president fires top commanders" Archived 4 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. hiiraan.com

- ↑ "Salad Gabeyre Kediye Was a Brigadier General in the Somali Military and a Revolutionary". Banaadir Weyne. 2 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Somalia changes its top military commanders". Shabelle Media Network. 13 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ https://english.aawsat.com/khalid-mahmoud/world-news/somalia-president-changes-military-leadership-declares-war-terror

- ↑ "Somalia: Military Chief warns counterfeit military ranks". Raxanreeb. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

References

- Defense Intelligence Agency, 'Military Intelligence Summary, Vol IV, Part III, Africa South of the Sahara', November 1987

- International Crisis Group, Somalia: The Transitional Government on Life Support, Africa Report 170, 20 February 2011.