Berbera

| Berbera Barbara بربرة | |

|---|---|

| City | |

_(2).jpg) _(2).jpg) _(2).jpg)   | |

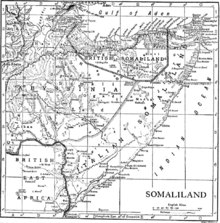

Berbera Location in Somaliland | |

| Coordinates: 10°26′08″N 045°00′59″E / 10.43556°N 45.01639°ECoordinates: 10°26′08″N 045°00′59″E / 10.43556°N 45.01639°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Sahil |

| District | Berbera |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Abdishakur Iddin [1] |

| Elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Population (2015)[2] | |

| • Total | 300,070 |

| Demonym(s) | Berberawi |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

Berbera (Somali: Barbara, Arabic: بربرة) is a coastal city and capital of Sahil region of Somaliland and the former capital of Somaliland.[3][4]

In antiquity, Berbera was part of a chain of commercial port cities along the Somali seaboard. It later served as the capital of the British Somaliland protectorate from 1884 to 1941, when it was replaced by Hargeisa. In 1960, the British Somaliland protectorate gained independence as the State of Somaliland and united five days later with the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somalia) to form the Somali Republic.[5][6] Located strategically on the oil route, the city has a deep seaport, which serves as the region's main commercial harbour.

History

Antiquity

During the antiquity times. Berbera was part of the Somali city-states that in engaged in a lucrative trade network connecting Somali merchants with Phoenicia, Ptolemic Egypt, Greece, Parthian Persia, Saba, Nabataea and the Roman Empire. Somali sailors used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.[7]

Berbera preserves the ancient name of the coast along the southern shore of the Gulf of Aden. It is thought to be the city Malao described as 800 stadia beyond the city of the Avalites, described in the eighth chapter of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, which was written by a Greek merchant in the first century AD. In the Periplus it is described as

an open roadstead, sheltered by a spit running out from the east. Here the natives are more peaceable. There are imported into this place the things already mentioned, and many tunics, cloaks from Arsinoe, dressed and dyed; drinking-cups, sheets of soft copper in small quantity, iron, and gold and silver coin, not much. There are exported from these places myrrh, a little frankincense, (that known as far-side), the harder cinnamon, duaca, Indian copal and macir, which are imported into Arabia; and slaves, but rarely.[8]

Middle ages

Duan Chengshi, a Chinese Tang dynasty scholar, described in his written work of AD 863 the slave trade, ivory trade, and ambergris trade of Bobali, which is thought to be Berbera. The great city was also later mentioned by the Islamic traveller Ibn Sa'id as well as Ibn Battuta in the thirteenth century.[9]

%2C_Woqooyi_Galbeed%2C_Berbera_(1).jpg)

Berbera was a powerful and well built city that served as a major harbor port for various of powerful Somali Kingdoms in the Middle Ages like the early Adal Kingdom, Ifat Sultanate and Adal Sultanate.[10] It also made Zeila the regional capital due to the latter's strategic location on the Red Sea.

Early modern period

One certainty about Berbera over the following centuries was that it was the site of an annual fair, held between October and April, which Mordechai Abir describes as "among the most important commercial events of the east coast of Africa."[11] The major Somali clan of Isaaq in Somaliland, caravans from Harar and the Hawd, and Banyan merchants from Porbandar, Mangalore and Mumbai gathered to trade. All of this was kept secret from European merchants, writes Abir: "Banyan and Arab merchants who were concerned with the trade of this fair closely guarded all information which might have helped new competitors; and actually through the machinations of such merchants Europeans were not allowed to take part in the fair at all."[12] Lieutenant C. J. Cruttenden, who wrote a memoir describing this portion of the Somali coast dated 12 May 1848, provided an account of the Berbera fair and an account of the only visible traces of man at the site: "an aqueduct of stone and chunam, some nine miles [15 km] in length", which had once emptied into a presently dry reservoir adjacent to the ruins of a mosque. He explored part of its course from the reservoir past a number of tombs built of stones taken from the aqueduct to reach a spring, above which lay "the remains of a small fort or tower of chunam and stone ... on the hill-side immediately over the spring." Cruttenden noted that in "style it was different to any houses now found on the Somali coast", and concluded with noting the presence in "the neighbourhood of the fort above mentioned [an] abundance of broken glass and pottery ... from which I infer that it was a place of considerable antiquity; but, though diligent search was made, no traces of inscriptions could be discovered."[13]

The British explorer Richard Burton made two visits to this port, and his second visit was marred by an attack on his camp by several hundred Somali spearmen the night of 19 April 1855, and although Burton was able to escape to Aden, one of his companions was killed.[14] Burton, recognizing the importance of the port city wrote:

In the first place, Berberah is the true key of the Red Sea, the centre of East African traffic, and the only safe place for shipping upon the western Erythraean shore, from Suez to Guardafui. Backed by lands capable of cultivation, and by hills covered with pine and other valuable trees, enjoying a comparatively temperate climate, with a regular although thin monsoon, this harbour has been coveted by many a foreign conqueror. Circumstances have thrown it as it were into our arms, and, if we refuse the chance, another and a rival nation will not be so blind."[15]

It was not long before these words proved prescient.

In 1874–75, the Egyptians obtained a firman from the Ottomans by which they secured claims over the city. At the same time, the Egyptians received British recognition of their nominal jurisdiction as far east as Cape Guardafui.[16] In actuality, however, Egypt had little authority over the interior and their period of rule on the coast was brief, lasting only a few years (1870–84).[17]

British Somaliland

In 1888, after signing successive treaties with the various Sultans of the Isaaq's Clans, the British established a protectorate in the region referred to as British Somaliland.[18] The British garrisoned the protectorate from Aden and administered it from their British India colony until 1898. British Somaliland was then administered by the Foreign Office until 1905 and afterwards by the Colonial Office.

Generally, the British did not have much interest in the resource-barren region, In fact Winston Churchill once visited Berbera in 1907 when he was Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies he noted that protectorate be abandoned, since it was unproductive, inhospitable, and the people were very hostile to the occupation, he also stated that the governor's residence "was unfit for a decent English dog".[19] The stated purposes of the establishment of the protectorate were to "secure a supply market, check the traffic in slaves, and to exclude the interference of foreign powers." [20] The British principally viewed the protectorate as a source for supplies of meat for their British Indian outpost in Aden through the maintenance of order in the coastal areas and protection of the caravan routes from the interior.[21][22] Colonial administration during this period did not extend administrative infrastructure beyond the coast,[23] and contrasted with the more interventionist colonial experience of Italian Somalia.[24]

In August 1940, during the East African Campaign, British Somaliland was briefly occupied by Italy after a large invasion force defeated British colonial troops at the Battle of Tug Argan. During this period, the British rounded up soldiers and governmental officials to evacuate them from the territory through Berbera. In total, 7,000 people, including civilians, were evacuated.[25] The Somalis serving in the Somaliland Camel Corps were given the choice of evacuation or disbandment; the majority chose to remain and were allowed to retain their arms.[26] In March 1941, the British forces recaptured the protectorate during Operation Appearance after a six-month occupation. The first WW2 Australian POWs were taken hostage here in 1940.

The British Somaliland protectorate gained its independence on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland,[27][28] before uniting as planned five days later with the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somalia) to form the Somali Republic.[6][27]

Modern

_(2).jpg)

In the post-independence period, Berbera was administered as the part of the North-Western province of the Somali Republic. After the collapse of the Somali central government and the ouster of the Dictatorship of General Siad Barre in 1991, Somali National Movement (SNM), which was an insurgent movement fighting to remove the yoke of the Barre's dictatorship from the Northern region of the Somali Republic declared the national independence of Somaliland Republic. A slow process of infrastructural reconstruction subsequently began in Berbera and other towns in the region.

Geography

Location and habitat

_(2).jpg)

Berbera is located in coastal region of Somaliland Republic. An old port city, it has the only sheltered harbour on the southern side of the Gulf of Aden. The landscape around town, along with Somaliland's coastal lowlands, is semi-arid land.

Popular local beaches, such as Bathela and Batalale, have earned the city the nickname Beach City.

Climate

_(2).jpg)

Berbera features a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). It has long, very hot summers and short, hot winters, as well as very little rainfall. Average high temperatures consistently exceed 40 °C (104 °F) (104 °F) during nearly four months of summertime (June, July, August and September). Daytime heat on summer nights is high, with average low temperatures of around 30 °C (86 °F) (86 °F). During the coolest months of the year, average high temperatures remain above 29 °C (84 °F) (84.2 °F) and average low temperatures also surpass 20 °C (68 °F) (68 °F). Although precipitation is low, the relative humidity is very high throughout the year and the atmosphere is simultaneously moist. The combination of the desert heat and the excessive moisture make apparent temperatures reach extremely high levels. Annual average rainfall is minimal, with only 52 millimetres (2.0 inches) (2.05 in) of precipitation. There are between 5 and 8 rainy days on average annually. Bright sunshine likely occur during about 84% of the total daytime hours and average annual cloudiness is very low.

| Climate data for Berbera | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.3 (95.5) |

35.0 (95) |

35.0 (95) |

42.2 (108) |

47.3 (117.1) |

49.1 (120.4) |

47.7 (117.9) |

46.7 (116.1) |

46.0 (114.8) |

41.7 (107.1) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.1 (97) |

49.1 (120.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27.9 (82.2) |

29.2 (84.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

35.7 (96.3) |

42.8 (109) |

42.9 (109.2) |

41.9 (107.4) |

39.7 (103.5) |

33.1 (91.6) |

30.0 (86) |

28.6 (83.5) |

34.5 (94.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.0 (77) |

25.0 (77) |

26.1 (79) |

28.3 (82.9) |

31.1 (88) |

33.5 (92.3) |

36.1 (97) |

35.6 (96.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.0 (86) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.3 (70.3) |

21.6 (70.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.1 (88) |

29.3 (84.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

22.2 (72) |

21.6 (70.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.9 (66) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.2 (72) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.0 (68) |

17.8 (64) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.1 (61) |

15.0 (59) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 8 (0.31) |

2 (0.08) |

5 (0.2) |

12 (0.47) |

8 (0.31) |

1 (0.04) |

1 (0.04) |

2 (0.08) |

1 (0.04) |

2 (0.08) |

5 (0.2) |

5 (0.2) |

52 (2.05) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 5.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 73 | 49 | 44 | 45 | 51 | 72 | 74 | 76 | 67 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 80 | 80 | 80 | 83 | 83 | 87 | 80 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 80 | 83 |

| Source #1: Arab Meteorology Book (average temperatures, humidity and precipitation),[29] Deutscher Wetterdienst (precipitation days, 1908–1950 and extremes)[30] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Food and Agriculture Organization: Somalia Water and Land Management (percent sunshine)[31] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

As of 2015, Berbera city has an estimated population of 300,070 residents.[32] It is inhabited by people from the Issa Musse sub-clan of the Isaaq Somali ethnic group,.[33]

Education

There are 10 primary schools operating in Berbera city totaling 3,641 student. The broader Berbera district has 49 schools serving 6,310 student.[34]

Economy

A number of products are exported through the Port of Berbera, including sheep, gum arabic, frankincense, and myrrh. Its seaborne trade is chiefly with Aden in Yemen, 240 kilometres (150 miles) to the north.[35] Additionally, goods from Ethiopia are also exported through the facility.[36] The seaside boasts watersport tourist activity such as scuba diving, snorkeling, surfing and coral reefs.[37]

Transportation

Berbera is the terminus of roads from Hargeisa and Burco. The city has one of Somaliland's major class seaports, the Port of Berbera.[38] It historically served as a naval and missile base for the Somali government. Following a 1972 agreement between the Siad Barre administration and the USSR, the port's facilities were patronized by the Soviets.[39] The Berbera seaport was later expanded for U.S. military use, after the Somali authorities strengthened ties with the American government.[40]

For air transportation, the city is served by the Berbera Airport. It has an extensive 4,140-metre (13,580-foot) runway.[41]

References

- ↑ "Somaliland and DP World celebrate 30-year concession for $442 million Port of Berbera (Somaliland) – Asoko Insight". Asoko Insight. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ "Population data" (PDF). docs.unocha.org. 2005.

- ↑ "Issue 270". Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "The Transitional Federal Charter of the Somali Republic" (PDF). University of Pretoria. 1 February 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ Cahoon, Ben. "Somalia". www.worldstatesmen.org.

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p.835

- ↑ Journal of African History pg.50 by John Donnelly Fage and Roland Anthony Oliver

- ↑ The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, ch. 8

- ↑ I.M. Lewis, "The Somali Conquest of the Horn of Africa", Journal of African History, 1 (1960), p. 217

- ↑ I.M. Lewis, A Modern History of the Somali, fourth edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2002), p. 21

- ↑ w. Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: The Era of the Princes; The Challenge of Islam and the Re-unification of the Christian Empire (1769-1855). London: Longmans. p. 16.

- ↑ Abir, Era of the Princes, p. 17

- ↑ C. J. Cruttenden, "Memoir on the Western or Edoor Tribes, Inhabiting the Somali Coast of N.-E. Africa, with the Southern Branches of the Family of Darrood, Resident on the Banks of the Webbe Shebeyli, Commonly Called the River Webbe," Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 19 (1849), pp. 54, 56

- ↑ Lewis, A Modern History, p. 36

- ↑ Richard Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa, Preface

- ↑ E. H. M. Clifford, "The British Somaliland-Ethiopia Boundary", Geographical Journal, 87 (1936), p. 289

- ↑ I.M. Lewis, A Modern History of the Somali, fourth edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2002), p.43 & 49

- ↑ Hugh Chisholm (ed.), The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 25, (At the University press: 1911), p.383.

- ↑ Samatar, Abdi Ismail The state and rural transformation in Northern Somalia, 1884–1986, Madison: 1989, University of Wisconsin Press, p. 31

- ↑ Samatar p. 31

- ↑ Samatar, p. 32

- ↑ Samatar, Unhappy masses and the challenge of political Islam in the Horn of Africa, Somalia Online retrieved 10-03-27

- ↑ Samatar, The state and rural transformation in Northern Somalia, p. 42

- ↑ McConnell, Tristan (15 January 2009). "The Invisible Country". Virginia Quarterly Review. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Playfair (1954), p. 178

- ↑ Wavell, p. 2724

- 1 2 "Somaliland Marks Independence After 73 Years of British Rule" (fee required). The New York Times. 1960-06-26. p. 6. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ↑ "How Britain said farewell to its Empire". BBC News. 2010-07-23.

- ↑ "Appendix I: Meteorological Data" (PDF). Springer. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Berbera / Somalia" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ↑ "Long term mean monthly sunshine fraction in Somalia". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 2016-10-05. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ "Regions, districts, and their populations: Somalia 2005".

- ↑ Center for Creative Solutions (May 31, 2004), Ruin and Renewal: The Story of Somaliland, Hargeisa: Center for Creative Solutions, archived from the original on April 8, 2011, retrieved September 21, 2010,

The ‘Iise Muuse clan for whom Berbera and its environs are their traditional area of settlement saw it differently. Retrieved on 2011-12-15.

- ↑ "2011/2 Primary School Census Statistics Yearbook" (PDF).

- ↑ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Armed Services. Special Subcommittee to Inspect Facilities at Berbera, Somalia. (1975). Report of the Special Subcommittee to Inspect Facilities at Berbera, Somalia, to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, Ninety-fourth Congress, first session, July 15, 1975. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office.

- ↑ "Ethiopia, Somaliland envisage exploiting Barbara port", Ethiopian News Agency, 29 July 2009 (accessed 1 November 2009)

- ↑ Somalia attractions, Berbera Seaside retrieved 29 November 2013

- ↑ "Istanbul conference on Somalia 21 – 23 May 2010 - Draft discussion paper for Round Table "Transport infrastructure"" (PDF). Government of Somalia. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Hanhimäki, Jussi M. (2013). The Rise and Fall of Détente: American Foreign Policy and the Transformation of the Cold War. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 1612345867.

- ↑ Intercontinental Press Combined with Inprecor, Volume 20, Issues 25-37. Intercontinental Press. 1982. p. 674.

- ↑ Schmitz, Sebastain (2007). "By Ilyushin 18 to Mogadishu". Airways. 14 (7): 12–17. ISSN 1074-4320.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Berbera. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Berbera. |