Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict

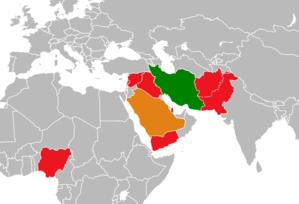

The Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict (sometimes referred to as the Iran–Saudi Arabia Cold War[72] or the Middle East Cold War)[73] is the ongoing struggle for influence in the Middle East and surrounding regions between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.[74] The two countries have provided varying degrees of support to opposing sides in nearby conflicts, including the civil wars in Syria,[75][76][77] Yemen,[78][79] and Iraq.[80] The rivalry also extends to disputes in Bahrain,[81] Lebanon,[82] Qatar,[83] Pakistan,[84][85] Afghanistan,[86][87] Nigeria,[88][89] and Morocco,[90] as well as broader competition in North and East Africa,[89][91] parts of South Asia,[92] Central Asia,[93][87] and the Caucasus.[94]

In what has been described as a cold war, the conflict is waged on multiple levels over geopolitical, economic, and sectarian influence in pursuit of regional hegemony.[1][95] American support for Saudi Arabia and its allies, Russian support for Iran and its allies, and increasing Chinese involvement on both sides have drawn comparisons to the dynamics of the Cold War era, and the proxy conflict has been characterized as a front in what Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev has referred to as the "New Cold War."[96][97][98][99]

History

Iranian Revolution

The proxy conflict can be traced back to the Iranian Revolution in 1979, when the monarchic Imperial State of Iran became an Islamic republic. The revolutionaries called for the overthrow of monarchies and secular governments to be replaced with Islamic republics, much to the alarm of Iran's smaller Sunni-run Arab neighbors Saudi Arabia, Ba'athist Iraq, Kuwait, and the other Persian Gulf states, most of whom were monarchies and all of whom had sizable Shia populations. Islamist insurgents rose in Saudi Arabia in 1979, Egypt and Bahrain in 1981, Syria in 1982, and Lebanon in 1983.

Prior to the Iranian Revolution, the two countries constituted the Nixon Doctrine's "twin pillar" policy in the Middle East.[100] The monarchies, particularly Iran, were allied with the US to ensure stability in the Gulf region and act as a bulwark against Soviet influence during the Arab Cold War between Saudi Arabia and Egypt under Gamal Abdel Nasser. The alliance acted as a moderating influence on Saudi-Iranian relations.[101]

During this period Saudi Arabia styled itself as the leader of the Muslim world, basing its legitimacy in part on its control of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. In 1962 it sponsored the inaugural General Islamic Conference in Mecca, at which a resolution was passed to create the Muslim World League. The organization is dedicated to spreading Islam and fostering Islamic solidarity under the Saudi purview, and has been successful in promoting Islam, particularly the conservative Wahhabi doctrine advocated by the Saudi government.[102] Saudi Arabia also spearheaded the creation of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in 1969.

Saudi Arabia's image as the leader of the Muslim world was undermined in 1979 with the rise of Iran's new theocratic government under Ayatollah Khomeini, who challenged the legitimacy of the Al Saud dynasty and its authority as Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques.[103][104] King Khalid initially congratulated Iran and stated that "Islamic solidarity" could be the basis of closer relations between the two countries, but relations worsened substantially over the next decade. In response to the 1987 Mecca incident in which Shia pilgrims clashed with Saudi security forces during the Hajj, Khomeini stated: "These vile and ungodly Wahhabis, are like daggers which have always pierced the heart of the Muslims from the back...Mecca is in the hands of a band of heretics."[105] Iran also called for the ouster of the Saudi government.[106]

Iran–Iraq War

In 1980, Saddam Hussein attempted to take advantage of revolutionary unrest in Iran and quell the revolution in its infancy. Fearing a possible revolutionary wave that could threaten Iraq's stability and embolden its Shia population, Saddam launched an invasion on 20 September, triggering the Iran–Iraq War which lasted for eight years and killed hundreds of thousands. Saddam had reportedly secured Saudi support for Iraq's war effort during an August 1980 visit he made to Saudi Arabia.[107] This was in addition to financial and military support Iraq received from neighboring leaders in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Kuwait, Jordan, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, in part to hedge Iranian power and prevent the spread of its revolution.

American support for Iraq during the war had profound effects on Iran. The United States' defense of Saddam and its role in blocking investigations into Iraq's use of chemical weapons on Iranian soldiers and civilians convinced Iran to further pursue its own unconventional weapons program. The government has also used American hostility to justify foreign and domestic policies, including its nuclear program and crackdowns on internal dissent.[108]

Apart from the Iran–Iraq War, Iran and Saudi Arabia engaged in tense competition elsewhere, supporting opposing armed groups in the Lebanese Civil War, the Soviet–Afghan War, and other conflicts. After the Cold War, Iran and Saudi Arabia continued to support different groups and organizations along sectarian lines such as in Afghanistan, Yemen, and Iraq.[109][110][111]

Arab Spring and Arab Winter

The current phase of the conflict began in 2011 when the Arab Spring sparked a revolutionary wave across the Middle East and North Africa, leading to revolutions in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen, and the outbreak of civil war in Libya and Syria. In response, Saudi Arabia called for the formation of a Gulf Union to deepen ties among the member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), a political and economic bloc founded in 1981. The proposal reflected the Saudi government's preoccupation with preventing potential uprisings by disenfranchised minorities in the Gulf monarchies as well as its regional rivalry with Iran.[112] The union would have centralized Saudi influence in the region by giving it greater control over military, economic, and political matters affecting member states. With the exception of Bahrain, members rejected the proposed federation, as Oman, Qatar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates were wary that it would lead to Saudi dominance.[113]

Due to the decreasing importance of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict as a wedge issue and mutual tensions with Iran, GCC states have sought strengthened economic and security cooperation with Israel, who is involved in its own proxy conflict with Iran.[114] Saudi Arabia has also become increasingly concerned about the United States' commitment as an ally and security guarantor. The American foreign policy pivot to Asia, its lessening reliance on Saudi oil, and the potential of rapprochement with Iran have all contributed to a more assertive Saudi foreign policy.[2] In 2015 Saudi Arabia formed the intergovernmental Islamic Military Alliance to Fight Terrorism (IMAFT) in December 2015 with the stated goal of combating terrorism. The coalition currently comprises 41 member states, all of which are led by Sunni-dominated governments. Shia-led Iran, Iraq, and Syria are notably excluded, something which has drawn concerns that the initiative is part of the Saudi effort to isolate Iran.[115][116]

The onset of the Arab Winter exacerbated Saudi concerns about Iran as well as its own internal stability. This prompted Riyadh to take greater action to maintain the status quo, particularly within Bahrain and other bordering states, with a new foreign policy described as a "21st century version of the Brezhnev Doctrine."[117][118] Iran took the opposite approach in hopes of taking advantage of regional instability by expanding its presence in the Shia crescent and creating a land corridor of influence stretching from Iraq to Lebanon, done in part by supporting Shia militias in the war against ISIL.[119][120]

While they all share concern over Iran, the Sunni Arab governments both within and outside of the GCC have long disagreed on political Islam. Saudi Arabia's Wahhabi religious establishment and its top-down bureaucracy differ from some of its allies such as Qatar, which promotes populist Sunni Islamist platforms similar to that of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey. Qatar has also drawn criticism from neighboring Sunni countries for its support of controversial transnational organizations like the Muslim Brotherhood, which as of 2015 is considered a terrorist organization by the governments of Bahrain, Egypt, Russia, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.[121] The United Arab Emirates, on the other hand, supports anti-Islamist forces in Libya, Egypt, Yemen and other countries, and is focused more on domestic issues, similar to Egypt under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. These differences make it unlikely that the Sunni world could unite against both Iran and terrorism, despite shared opposition.[122] Since King Salman came to power in 2015, Saudi Arabia has increasingly moved from its traditional Wahhabist ideological approach to a nationalist one, and has adopted a more aggressive foreign policy.[123]

The complex nature of economic and security concerns, ideological division, and intertwined alliances has also drawn comparisons to pre-World War I Europe.[124] The conflict also shares similarities with the Arab Cold War between Egypt and Saudi Arabia in the 1950s and 1960s. Influence was judged by each state's ability to affect the affairs of neighboring countries, non-state actors played significant roles, and disunity in both camps led to tactical alliances between states on opposing sides.[73][125]

2016

The 2015 Mina stampede in Mecca during the annual Hajj pilgrimage further inflamed tensions. Tehran blamed the Saudi government for the tragedy and accused them of incompetence, which Riyadh rejected.[126][127][128] In May 2016 Iran suspended participation in the upcoming Hajj.[129] In September, Saudi Arabia launched a 24-hour Persian language satellite channel to broadcast the Hajj proceedings from 10 to 15 September. Ayatollah Khamenei accused Riyadh of politicizing the Hajj tragedy and argued that Saudi Arabia should not be running the pilgrimage.[130][131]

On 2 January 2016, 47 people were put to death in several Saudi cities, including prominent Shiite cleric Nimr al-Nimr. Protesters of the executions responded by demonstrating in Iran’s capital, Tehran. That same day a few protesters would eventually ransack the Saudi Embassy in Tehran and later set it ablaze.[132] Police donned riot gear and arrested 40 people during the incident.[133][134][135] In response, Saudi Arabia, along with its allies, Bahrain, Sudan, Djibouti, Somalia, and the Comoros cut diplomatic ties with Iran.[136][137] Iran's foreign ministry responded by saying the Saudis were using the incident as a pretext for fueling tensions.[138]

In recent years, King Salman made significant changes in domestic policy to address growing unemployment and economic uncertainty.[139] Such economic pressures further affected the regional dynamic in 2016. Russia, who has long maintained ties with Iran, has also sought closer ties to Saudi Arabia. In September 2016, the two nations conducted informal talks about cooperating on oil production. Both have been heavily affected by the collapse of oil prices and considered the possibility of an OPEC freeze on oil output. As part of the talks, Russian President Vladimir Putin recommended an exemption for Iran, whose oil output has steadily increased following the lifting of international sanctions in January 2016. He stated that Iran deserves the opportunity to reach its pre-sanction levels of output.[140][141] In what was seen as a significant compromise, Saudi Arabia offered to reduce its oil production if Iran capped its own output by the end of 2016.[142]

Extremist movements throughout the Middle East have also become a major division between Iran and Saudi Arabia. During the Cold War, Saudi Arabia funded extremist militants in part to bolster resistance to the Soviet Union at the behest of the United States, and later to combat Shia movements supported by Iran. The support had the unintended effect of metastasizing extremism throughout the region. The Saudi government now considers extremist groups like ISIL and the Al-Nusra Front to be one of the two major threats to the kingdom and its monarchy, the other being Iran.[143] In a New York Times op-ed, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif agreed that terrorism was an international threat and called on the United Nations to block funding of extremist ideologies using Iran's WAVE initiative as a framework. However, he placed the blame on Saudi Arabia and its sponsorship of Wahhabism for instability in the Middle East. He argued that Wahhabism was the fundamental ideology shared among terrorist groups in the Middle East, and that it has been "devastating in its impact." He went so far as to proclaim "Let us rid the world of Wahhabism" and asserted that, despite arguments otherwise, Wahhabism was the true cause of the Iran–Saudi Arabia rivalry.[144]

The election of Donald Trump in the United States in 2016 prompted uncertainty from both countries about future US policy in the Middle East, as both were targets of criticism during his campaign. The Saudi government anticipated that the Trump administration would adopt a more hawkish stance than the Obama administration on Iran, which would potentially benefit Riyadh.[145] Iran feared the return of economic isolation, and President Hassan Rouhani made efforts to establish further international economic participation for the country by signing oil deals with Western companies before Trump took office.[146]

2017

In May 2017, Trump declared a shift in US foreign policy toward favoring Saudi Arabia at Iran's expense, marking a departure from President Obama's more reconciliatory approach. This move came days after the re-election of Rouhani in Iran, who defeated conservative candidate Ebrahim Raisi. Rouhani's victory was seen as a popular mandate for liberal reforms in the country.[147]

Several incidents in mid-2017 further heightened tensions. In May 2017, Saudi forces laid siege on Al-Awamiyah, the home of Nimr al-Nimr, in a clash with Shia militants.[148] Dozens of Shia civilians were reportedly killed. Residents are not allowed to enter or leave, and military indiscriminately shells the neighborhoods with artillery fire and snipers are reportedly shooting residents.[149][150][151] In June, the Iranian state-owned news agency Press TV reported that the president of a Quran council and two cousins of executed Nimr al-Nimr were killed by Saudi security forces in Qatif.[152][153] During the subsequent crackdown the Saudi government demolished several historical sites and many other buildings and houses in Qatif.[154] On 17 June, Iran announced that the Saudi coast guard had killed an Iranian fisherman.[155][156] Soon after, Saudi authorities captured three Iranian citizens who they claimed were IRGC members plotting a terrorist attack on an offshore Saudi oilfield.[157] Iran denied the claim, saying that those captured are regular fishermen and demanding their immediate release.[158]

In the wake of the June 2017 Tehran attacks committed by ISIL militants, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps issued a statement blaming Saudi Arabia, while Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir said there was no evidence that Saudis were involved.[159] Later Iranian official Hossein Amir-Abdollahian stated that Saudi Arabia is the prime suspect behind the Tehran attacks.[160] The commander of IRGC, Major General Mohammad Ali Jafari, claimed that Iran has intelligence proving Saudi Arabia's, Israel's, and the United States' involvement in the Tehran attack.[161] Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei later accused the United States of creating ISIL and of joining Saudi Arabia in funding and directing ISIL in addition to other terrorist organizations.[162]

In October 2017, the government of Switzerland announced an agreement in which it would represent Saudi interests in Iran and Iranian interests in Saudi Arabia. The two countries had severed relations in January 2016.[163]

Several major developments occurring in November 2017 drew concerns that that proxy conflict might escalate into a direct military confrontation between Iran and Saudi Arabia.[72][164] On 4 November the Royal Saudi Air Defense intercepted a ballistic missile over Riyadh International Airport. Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir asserted that the missile was supplied by Iran and launched by Hezbollah militants from territory held by Houthi rebels in Yemen. Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman called it "direct military aggression by the Iranian regime" and said that it "may be considered an act of war against the kingdom."[165] Also on 4 November, the Prime Minister of Lebanon resigned, sparking a political crisis seen as part of a Saudi effort to counteract Iran's influence in the country. Bahrain also blamed a 10 November explosion on its main oil pipeline on Iran.[166]

On 24 November 2017, Dubai's security chief Lieutenant General Dhahi Khalfan blamed the 2017 Sinai attack on Al-Jazeera and called for bombing of the network by a Saudi-led coalition.[167] In late November 2017, IRGC commander Jafari said revolutionary Islamic paramilitary forces had formed across the Middle East and surrounding regions to counter the influence of ultraconservative militant jihadi groups and Western powers.[168]

2018

Saudi Arabia under King Salman has adopted a more assertive foreign policy, particularly reflected in the country's intervention in Yemen in 2015 and its involvement in Lebanon in 2017. This has continued with the June 2017 appointment of Mohammad bin Salman as Crown Prince, who has been considered the power behind the throne for years.[169][170][171] The Crown Prince has referred to Iran, Turkey, and Islamic extremist groups as a "triangle of evil," and compared Supreme Leader Khamenei to Adolf Hitler.[172][173] The populist, anti-Iranian rhetoric comes at a time of uncertainty over potential fallout from Mohammad bin Salman's consolidation of power, and he has used the rivalry as a means to strengthen Saudi nationalism despite the country's domestic challenges.[123]

As part of the Saudi Vision 2030 plan, Mohammad bin Salman is pursuing American investment to aid efforts to diversify Saudi Arabia's economy away from oil.[174][173] The reforms also include moving the country away from Wahhabi conservatism, which the Crown Prince discussed in 2017: "What happened in the last 30 years is not Saudi Arabia. What happened in the region in the last 30 years is not the Middle East. After the Iranian revolution in 1979, people wanted to copy this model in different countries, one of them is Saudi Arabia. We didn't know how to deal with it. And the problem spread all over the world. Now is the time to get rid of it."[175]

Both Israel and Saudi Arabia supported the US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal.[174][176] In anticipation of the withdrawal, Iran indicated it would continue to pursue closer ties to Russia and China, with Ayatollah Khamenei stating in February 2018: "In foreign policy, the top priorities for us today include preferring East to West."[177] The unilateral decision by the United States drew concerns of increased tensions with Russia and China, both of which are parties to the nuclear agreement.[176] It also heightened tensions in the Middle East, raising the risk of a larger military conflict breaking out involving Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Iran.[178][179]

The United States reinstated sanctions against Iran in August 2018 despite opposition from European allies.[180] The Trump administration also pushed for a military alliance with Sunni Arab states to act as a bulwark against Iran. The plan in consideration would establish a "Middle East Strategic Alliance" with six GCC states in addition to Jordan and Egypt.[181]

Involved parties

Iranian supporters and proxies

Hezbollah

Shi'ite separatists in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabian supporters and proxies

Gulf Cooperation Council

The Gulf Cooperation Council, an alliance of Sunni Arab States of the Gulf region including Saudi Arabia, has often been described as a Saudi headed alliance to counter Iran, which engaged pro-Saudi interests in Bahrain.[182]

People's Mujahedin of Iran

MEK, a long existing rebel Iranian group has received an increasing support from Saudi Arabia.[183][184]

Kurdish insurgents

Saudi Arabia has allegedly provided support to the Kurdish militants within the KDPI and PAK through its consulate in Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraqi Kurdistan.[185]

Jaish al-Udl

The rebel group Jaish ul-Adl, active in the Sistan and Baluchestan region of Iran, was accused by Iranian authorities of receiving Saudi support.[17]

Others

Israel

The speaker of Iran's parliament, Ali Larijani, stated that Saudi Arabia gave "strategic" intelligence information to Israel during the 2006 Lebanon War.[186] In May 2018, Israeli defense minister Avigdor Lieberman supported greater discussion between Israel, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, stating "It's time for the Middle East to [...] have an axis of moderate countries," opposed to the network of Iranian allies and proxies.[187] As of 2018, several sources described alleged intelligence ties between Saudi Arabia and Israel as a "covert alliance", with a joint interest to counter Iran in the region.[188] The New York Times remarked that such cooperation was made more difficult by controversy over Israel's attitude towards Palestinians.[189]

Palestine

In 2016, Al-Monitor mentioned an alleged meeting of the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas with the head of MEK Maryam Rajavi with Saudi backing.[190]

Jordan

United States

France

Pakistan

Other involved parties

Qatar

Qatar–Saudi Arabia relations have been strained since the beginning of the Arab Spring.[191] Qatar has been a focus of controversy in the Saudi-Iranian rivalry due to Saudi Arabia's longstanding concern about the country's relationship with Iran and Iranian-backed militant groups.[192]

In June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Egypt, the Maldives, Mauritania, Mauritius, Sudan, Senegal, Djibouti, Comoros, Jordan, the Tobruk-based Libyan government, and the Hadi-led Yemeni government severed diplomatic relations with Qatar and blocked their airspace and sea routes, in addition to Saudi Arabia blocking the only land crossing. The reasons cited were Qatar's relations with Iran, Al-Jazeera's coverage of other GCC states and Egypt, and Qatar's alleged support of Islamist groups.[193][194] Qatar was also expelled from the anti-Houthi coalition.[195] Qatar's defense minister Khalid bin Mohammed Al Attiyah called the blockade akin to a bloodless declaration of war, and Qatar's finance minister Ali Sharif Al Emadi stated that Qatar was rich enough to withstand the blockade.[196][197]

The bloc sought a guarantee that Qatar will in the future align in all matters with other Gulf states, discuss all of its decisions with them, and provide regular reports on its activity (monthly for the first year, quarterly for the second, and annually for the following ten years). They also demanded the deportation of all political refugees who live in Qatar to their countries of origin, freezing their assets, providing any desired information about their residency, movements, and finances, and revoking their Qatari citizenship if naturalized. They also demanded that Qatar be forbidden from granting citizenship to any additional fugitives.[198][199] Upon Qatar's rejection of these demands, the countries involved announced that the blockade would remain in place until Qatar changed its policies.[200][201] On 24 August 2017, Qatar announced that they would restore full diplomatic relations with Iran.[202]

Russia

Russia has been aligned with Iran and Syria for years. It intervened in Syria to provide support for the Assad government and to target rebel groups, working together with Iran and using Iranian air bases to stage air strikes.[203] It also joined Iran, Iraq, and Syria in forming a joint intelligence-sharing coalition as part of the fight against ISIL.[204] The alliance coincided with the US-led coalition created a year earlier to fight ISIL. The competing military actions were seen as part of a larger proxy conflict between the United States and Russia.[205][206][207]

China

In a conversation with King Salman in March 2018, Chinese President Xi Jinping expressed interest in increased strategic cooperation with Saudi Arabia. Although it has traditionally stayed out of the conflict despite relying on the region for oil, China has recently played both sides, and has had ties with Tehran for years.[98][99] Although it has warm relations with the Assad government, China has not gotten directly involved in the Syrian Civil War, instead supporting the Russian-led peace process and investing in Syria's reconstruction.[208] China's increased involvement in the region has come at a time when Xi Jinping has sought to expand China's global influence.[209]

Involvement in regional conflicts

Syrian Civil War

Syria has been a major theater in the proxy conflict throughout its ongoing civil war, which began in 2011. Iran and the GCC states have provided varying degrees of military and financial support to opposing sides, with Iran backing the government and Saudi Arabia supporting rebel militants.

Syria is an important part of Iran's sphere of influence, and the government under Bashar al-Assad has long been a major ally. During the early stages of the Arab Spring, Supreme Leader Khamenei initially expressed support for the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, characterizing them as an "Islamic awakening" akin to its own revolution in 1979. When protests broke out in Syria, Iran changed its position and condemned them, comparing the uprising to its own presidential election protests in 2009 and accusing the United States and Israel of being behind the unrest.[210]

The war threatens Iran's position, and Saudi Arabia and its allies have sided with Sunni rebels in part to weaken Iran. For years Iranian forces have been involved on the ground, with soldiers in Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps facing heavy casualties.[211] In 2014, with no end in sight to the conflict, Iran increased its ground support for the Syrian Army, providing elite forces, intelligence gathering, and training. Iran also backs pro-Assad Hezbollah fighters.[212] Although Iran and Saudi Arabia agreed in 2015 to participate in peace talks in Vienna in participation with United States Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, the talks ultimately failed.[213]

Saudi Arabia countered Russia's intervention in Syria by increasing its support for the rebels and supplying American-made anti-tank TOW missiles, a move which slowed initial progress made by Russian and Syrian forces.[214]

Yemeni Civil War

Yemen has been called one of the major fronts in the conflict as a result of the revolution and subsequent civil war.[215][216] Yemen had for years been within the Saudi sphere of influence. The decade-long Houthi insurgency in Yemen stoked tensions with Iran, with accusations of covert support for the rebels. A 2015 UN report alleged that Iran provided the Houthi rebels with money, training, and arms shipments beginning in 2009.[217] However, the degree of support has been subject to debate, and accusations of greater involvement have been denied by Iran.[218][219][220] The 2014–2015 coup d'état was viewed by Saudi leadership as an immediate threat, and as an opportunity for Iran to gain a foothold in the region. In March 2015, a Saudi-led coalition of Arab states, including all GCC members except Oman, intervened and launched airstrikes and a ground offensive in the country, declaring the entire Saada Governorate a military target and imposing a naval blockade.[221]

The United States intervened in October 2016 after missiles were fired at a US warship, which was in place to protect oil shipments along the sea lane passing through the Mandeb Strait. The US blamed the rebels and responded by targeting radar sites with missile strikes along the Red Sea coast. In response, rebels called the strikes evidence of American support for the Saudi campaign.[222][223]

Iraqi Civil War

While the majority of Muslims in Iraq are Shia, the country has been ruled for decades by Sunni-dominated governments under the Ottoman Empire, the British-installed Hashemites, and the Ba'athists. Under the rule of Saddam Hussein, Iraq was hostile to both Iran and Saudi Arabia and acted as a counterbalancing regional power. The American-led invasion in 2003 caused a power vacuum in the region. With the antagonistic Ba'athist regime removed, Iran sought a more friendly Shia-dominated government and supported sympathetic rebel factions as part of an effort to undermine the coalition, which Iran feared would install a government hostile to its interests.[224]

Saudi Arabia remained more passive during the occupation of Iraq, taking caution to preserve its relations with the United States by avoiding any direct support of Sunni insurgent groups. Riyadh supported the Bush administration's commitment to stay in the country, as it limited Iran's influence.[225] The edicts issued in May 2003 by Coalition Provisional Authority Administrator Paul Bremer to exclude members of the Ba'ath Party from the new Iraqi government and to disband the Iraqi Army undermined the occupation effort. The orders empowered various insurgent factions and weakened the new government's functional capabilities, leaving Iraq vulnerable to future instability.[226]

Following the United States withdrawal from Iraq in December 2011, the country drifted further into Iran's sphere of influence. The instability that resulted from the Iraqi Civil War and the rise of ISIL threatened the existence of the Iraqi regime and led to an Iranian intervention in 2014. Iran mobilized Shia militia groups to halt and ultimately push back the advancing Sunni insurgency[227], though the resurgence of ISIL in Iraq remains more than a possibility.[228]

The Iraqi government remains particularly influenced by Iran, and consults with it on most matters.[229] As of 2018 Iran has become Iraq's top trading partner, with an annual turnover of approximately $12 billion USD compared to the $6 billion USD in trade between Iraq and Saudi Arabia. In addition to fostering economic ties, Tehran furthered its influence by aiding the Iraqi government in its fight against the push for independence in Iraqi Kurdistan.[230] Saudi Arabia has responded by strengthening its ties to the Kurdistan Regional Government, seeing it as a barrier to the expansion of Iranian influence in the region, while also adopting a soft power approach to improve relations with the Iraqi government.[231][232]

Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, former Ba'athist official and leader of the Naqshbandi Army insurgent group, has repeatedly praised Saudi efforts to constrain Iranian clout in Iraq.[233][234]

Recently, Saudi Arabia has developed a close relationship with Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, the leader of the Sadrist Movement and the Peace Companies militia.[235]

Bahraini uprising

Saudi Arabia and Iran have sought to extend their influence in Bahrain for decades. While the majority of Muslims in Bahrain are Shia, the country is ruled by the Sunni Al Khalifa family. Iran claimed sovereignty over Bahrain until 1970, when Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi abandoned claims after negotiations with the United Kingdom.[236] The Iranian Revolution led to resumed interest in Bahraini affairs. In 1981, the front organization Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain led a failed coup attempt to install a Shia theocratic regime led by Hadi al-Modarresi. Since then, the government has accused Iran of supporting terrorist plots within its borders.[237]

Sunni states have long feared that Iran might stir up unrest among regional Shia minority populations, especially in Bahrain. The Al Khalifa regime's stability depends heavily on Saudi support. The island is connected to Saudi Arabia by the 25 kilometer King Fahd Causeway, and its proximity to Saudi Arabia's oil-rich, majority Shia Eastern Province is viewed by Riyadh as a security concern. Any political gains by the Shia in Bahrain are seen by the Saudis as gains for Iran.[238]

In response to the Arab Spring in 2011, the GCC regimes sought to maintain their legitimacy through social reform, economic handouts, and violent repression. Member states also distributed a share of their combined oil wealth to Bahrain and Oman to maintain stability.[239] Saudi-led GCC forces quickly intervened in support of the Al Khalifa regime to put down the anti-government uprising in Bahrain.

The Bahraini government publicly blamed Iran for the protests, but an independent commission established by King Hamad rejected the claim, instead highlighting human rights abuses committed in the crackdown.[240][71] The protests, along with the Iran nuclear deal, strained Bahrain's relationship with the United States. Bahrain has sought closer ties with Russia as a result, but this has been limited due to Saudi Arabia's alliance with the US.[241]

Following the onset of the Arab Winter, Bahrain accused Iran of orchestrating several domestic incidents as part of a campaign to destabilize the country. Tehran denied all allegations and accused the government of Bahrain of blaming its own internal problems on Iran after every incident.[166] In August 2015, authorities in Bahrain arrested five suspects over a bombing in Sitra. Officials linked the attacks to the Revolutionary Guard and Hezbollah, although Iran denied any involvement.[242] In January 2016, Bahrain joined Saudi Arabia in cutting diplomatic ties with Tehran following the attacks on Saudi diplomatic missions in Iran.[243] In November 2017, Bahrain called an explosion on its main oil pipeline "terrorist sabotage" linked to Iran, drawing a rebuke from Tehran. Saudi Arabia also referred to the incident as an "attack on the pipeline."[166]

Lebanese arena

In 2008, Saudi Arabia proposed creating an Arab force backed by US and NATO air and sea power to intervene in Lebanon and destroy Iranian-backed Hezbollah, according to a US diplomatic cable released by WikiLeaks. According to the cable Saudi argued that a Hezbollah victory against the Siniora government "combined with Iranian actions in Iraq and on the Palestinian front would be a disaster for the US and the entire region."[244][245]

In February 2016 Saudi Arabia and the UAE banned their citizens from visiting Lebanon and suspended military aid due to possible Iranian influence and Lebanon's refusal to condemn the attack on Saudi embassy.[246][247]

Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigned on 4 November 2017. The situation was seen as a power play by Saudi Arabia to increase its influence in Lebanon and counterbalance Iran's victories in Iraq and Syria.[248][249] In a televised speech from Saudi Arabia, Hariri criticized Hezbollah and blamed Iran for causing "disorder and destruction" in Lebanon. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah responded by accusing Hariri of resigning on Riyadh's orders.[250]

War in Afghanistan

The rivalry has contributed to the ongoing instability in Afghanistan. Afghanistan shares historical ties with Iran, and is strategically important to Saudi Arabia. After the Cold War, Saudi policy shifted from fighting the spread of communism to containing Iranian influence in South and Central Asia.[87]

Saudi Arabia was one of three countries to officially recognize the Sunni Taliban government in 1996, along with its allies Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates. During the Afghan Civil War, Iran and Saudi Arabia supported opposing militant factions. Iran assisted the Shia Hizb-i-Wahdat, while Saudi Arabia provided financial support to the Wahhabist Ittihad-i Islami.[251]

In 2001, the invasion of Afghanistan and the removal of the Taliban in the wake of the September 11 attacks benefited Iran, which had previously been on the brink of war with the group. The regime change removed Iran's primary threat along its eastern borders, and the removal of Saddam Hussein two years later further bolstered its position, allowing it to refocus its efforts on other areas, especially Syria and Yemen.[252] In the ensuing years, Iran sought to expand its influence over Afghanistan. It provided limited support to the Taliban as a potential means of increasing leverage with the Afghan central government and creating a deterrent to conflict with the United States, although the support waned amid growing backlash in Afghanistan against perceived Iranian interference.[253] Iran has also sought to expand soft influence by building pro-Iranian schools, mosques, and media centers, and by maintaining close ties with Afghanistan's Tajik and Hazara populations.[253]

Pakistani sectarian violence

Since 1989 Pakistan has been dealing with sectarian conflict. The population is predominantly Sunni and has about 10-15% of Shia adherents.[254]

Pakistan is economically dependent on Saudi Arabia and a key strategic ally. The country's economic stability relies heavily on foreign workers who send money home. The largest amount comes from the 1.5 million Pakistanis working in Saudi Arabia who sent home about $5.5 billion USD in remittances in 2017.[255] Saudi Arabia has invested in the country's nuclear weapons projects, and believes it could use Pakistan to quickly obtain nuclear weapons at will.[256] Riyadh also sees the province of Balochistan as a potential means of stirring ethnic unrest in neighboring Iran.[257]

In 2015, Pakistan declared its neutrality in the conflict in Yemen after Saudi solicitations for military support. It ultimately provided some degree of covert support, joining Somalia in sending proxy forces to aid the Saudi-led campaign against Houthi rebels.[45] In 2016, Saudi Arabia sought closer ties with Pakistan as part of its "look east" policy of expanding its reach to East and South Asia.[258]

In February 2018, Saudi Arabia, acting on behalf of the GCC, joined China and Turkey in opposing a US-led initiative to place Pakistan on an international terror-financing watch list through the Financial Action Task Force. This move came days after Pakistan pledged to send 1,000 troops to the Gulf kingdoms for what it described as an advisory mission.[255]

Iran has been accused of influencing young Pakistani Shias to act as proxies to further Iranian interests in Pakistan. The Iranian government has been suspected of militarizing Shia loyalists amongst Pakistan's local population and promoting sectarian sentiments to further achieve its goals.[259] Many Pakistani Shias have also been suspected of traveling to parts of the Middle East including Syria and Lebanon to fight on behalf of the Iranian government.[260][261][262]

Nuclear programs of Iran and Saudi Arabia

Although both Iran and Saudi Arabia signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in 1970 and 1988 respectively, a potential nuclear arms race has been a concern for years. Both governments claim that their programs are for peaceful purposes, but foreign governments and organizations have accused both of taking steps to obtain nuclear weapons capabilities.

Iran's ongoing nuclear program began in the 1950s under the Shah in cooperation with the United States as part of the Atoms for Peace program. The cooperation continued until the Iranian Revolution in 1979.[263] Sanctions have been in place since then, and were expanded in 2006 with the passage of United Nation Security Council Resolution 1737 and Resolution 1696 in response to Iran's uranium enrichment program.

Saudi Arabia has considered several options in response to the Iranian program: acquiring its own nuclear capability as a deterrent, entering into an alliance with an existing nuclear power, or pursuing a regional nuclear-weapon-free zone agreement.[264] It is believed that Saudi Arabia has been a major financier of Pakistan's integrated nuclear program since 1974, a project begun under former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. In 2003 it was reported that Saudi Arabia had taken the "strategic decision" to acquire "off-the-shelf" atomic weapons from Pakistan, according to senior American officials.[265] In 2003, The Washington Times reported that Pakistan and Saudi Arabia had entered a secret agreement on nuclear cooperation to provide the Saudis with nuclear weapons technology in return for access to cheap oil for Pakistan.[266]

Following several years of negotiations for a nuclear deal framework between Iran and the P5+1 countries, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was signed in 2015. The deal raised concerns for Saudi Arabia, which saw it as a step toward reducing Iran's international isolation and potentially exacerbating the proxy conflict.[267] However, Riyadh did not publicly denounce the deal at the time as Israel did.[268] In 2018, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman stated that Saudi Arabia would move to obtain nuclear weapons if Iran's program is successful.[269] He led a delegation to the United States to meet with Trump administration officials to discuss mutual concerns, including a potential US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear agreement.[174] In April 2018, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu gave a televised speech accusing Iran of covertly continuing the AMAD Project in violation of the JCPOA.[270]

President Trump announced on 8 May 2018 that the United States would unilaterally withdraw from the JCPOA and reinstate previous sanctions against Iran in addition to imposing new sanctions.[176] In anticipation of the decision, Iranian President Rouhani stated that Iran would remain in the deal if the remaining parties did the same, but was otherwise vague on how the country would respond to the US decision.[271]

See also

References

- 1 2 Joyner, Alfred (4 January 2016). "Iran vs Saudi Arabia: The Middle East cold war explained". International Business Times. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- 1 2 Poole, Thom (20 October 2017). "Iran and Saudi Arabia's great rivalry explained". BBC News. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ "Bahrain: Widespread Suppression, Scant Reforms". Human Rights Watch. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ Henderson, Simon (12 June 2014). "The Battle for Iraq Is a Saudi War on Iran". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Wintour, Patrick (7 June 2017). "Qatar: UAE and Saudi Arabia step up pressure in diplomatic crisis". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ Chulov, Martin (4 January 2016). "Saudi Arabia cuts diplomatic ties with Iran after execution of cleric". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Bahrain cuts diplomatic ties with Iran". Al Jazeera. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia and Gulf allies warn against Lebanon travel". BBC News. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Daoud, David (March 2015). "Meet the Proxies: How Iran Spreads Its Empire through Terrorist Militias". The Tower Magazine (24). Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Hashim, Ahmed Salah (29 January 2016), "Saudi-Iranian Rivalry and Conflict: Shia Province as Casus Belli?" (PDF), RSIS Commentary, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (22), retrieved 18 August 2016

- ↑ Abedin, Mahan (26 October 2006). "Saudi Shi'ites: New light on an old divide". Asia Times. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ Goulka, Jeremiah; Hansell, Lydia; Wilke, Elizabeth; Larson, Judith (2009). "The Mujahedin-e Khalq in Iraq: a policy conundrum" (PDF). RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-4701-4.

- ↑ Mousavian, Seyed Hossein (21 July 2016). "From Iran to Nice, We Must Confront All Terrorism to End Terrorism". Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Karami, Arash (2 August 2016). "Were Saudis behind Abbas-MEK meeting?". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Iddon, Paul (28 July 2016). "Erbil is not another front in the Saudi-Iran regional proxy war". Rudaw. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ↑ Dehghanpisheh, Babak (4 September 2016). "To Iranian eyes, Kurdish unrest spells Saudi incitement". Reuters. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- 1 2 Merat, Arron (28 March 2014). "Iran calls for return of abducted border guards held in Pakistan". The Telegraph. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ http://www.irna.ir/en/News/83040635

- ↑ https://www.alwatanvoice.com/arabic/news/2015/07/03/738470.html

- ↑ Jansen, Michael (23 August 2016). "China enters fray in Syria on Bashar al-Assad's side". The Irish Times. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ http://www.businessinsider.com.au/iraq-joins-assads-side-in-syrian-war-2013-3

- ↑ See:

- "Report: Iran, North Korea Helping Syria Resume Building Missiles". Nuclear Threat Initiative. 28 January 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Ryall, Julian (6 June 2013). "Syria: North Korean military 'advising Assad regime'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- "North Korea violating sanctions, according to UN report". The Telegraph. 3 July 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ https://arabic.cnn.com/middleeast/2016/05/07/algeria-syria-relationship-analysis-0

- ↑ https://www.masress.com/almesryoon/450013

- ↑ http://elaph.mobi/Web/News/2015/10/1048301.html

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/31/victory-for-assad-looks-increasingly-likely-as-world-loses-interest-in-syria

- 1 2 Van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (12 June 2015). "The Rise of Jaysh al-Fateh in Northern Syria". Terrorism Monitor. Vol. XIII no. 12. Jamestown Foundation. p. 3.

- 1 2 Porter, Gareth (28 May 2015). "Gulf allies and 'Army of Conquest'". Al-Ahram Weekly.

- ↑ Maclean, William; Finn, Tom (26 November 2016). "Qatar will help Syrian rebels even if Trump ends U.S. role". Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ↑ https://youm7.com/story/2014/12/8/%D9%85%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%AC%D8%A3%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D8%B4%D9%81-%D8%B9%D9%86-%D8%A3%D8%AF%D9%82-%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%B5%D9%8A%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%82%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%B4-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%89-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D8%B1-%D8%A8%D8%A5%D8%B3%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%8A%D9%84/1982184

- ↑ "Yemen accuses Russia of supplying weapons to Houthi rebels". UNIAN. 5 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Masi, Alessandria (25 September 2015). "Putin's Latest Moves: The Military Alliance Among Iran, Hezbollah And Russia In Syria Could Spread To Yemen". International Business Times. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

Moscow is now supporting the Tehran-backed Houthi rebels who are fighting forces loyal to the U.S.-supported exiled president.

- ↑ "North Korea Likely Supplied Scud Missiles Fired at Saudi Arabia by Yemen's Houthi Rebels". Vice News. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ↑ See:

- Al-Abyad, Said (11 March 2017). "Yemeni Officer: 4 Lebanese 'Hezbollah' Members Caught in Ma'rib". Asharq Al-Awsat. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Pestano, Andrew V. (25 February 2016). "Yemen accuses Hezbollah of supporting Houthi attacks in Saudi Arabia". Sana'a, Yemen: United Press International. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Hatem, Mohammed (24 February 2016). "Yemen Accuses Hezbollah of Helping Houthis in Saudi Border War". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Yemen government says Hezbollah fighting alongside Houthis". Reuters. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Report: Houthi Commander Admits Iran, Hezbollah Training Fighters in Yemen". The Tower. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ↑ https://marebpress.net/news_details.php?lng=arabic&sid=109003

- ↑ https://www.elnashra.com/news/show/892879/السفير-اليمني-السابق-سوريا-النظام-السوري-درب-الحوث

- ↑ https://www.akhbaralaan.net/news/arab-world/2018/8/4/تقرير-أممي-التعاون-بين-بيونغ-يانغ-والنظام-السوري-مستمر

- ↑ https://www.watanserb.com/2018/08/16/%D9%82%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%8A-%D8%AD%D9%88%D8%AB%D9%8A-%D9%85%D9%86%D8%B4%D9%82-%D8%A3%D8%B1%D8%AA%D9%85%D9%89-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A3%D8%AD%D8%B6%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF%D9%8A/

- ↑ http://www.masrawy.com/news/news_publicaffairs/details/2018/3/26/1292017/%D8%A7%D8%AA%D9%87%D8%A7%D9%85-%D9%82%D8%B7%D8%B1-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B6%D9%84%D9%88%D8%B9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%AA%D9%85%D9%88%D9%8A%D9%84-%D8%A3%D8%B9%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%88%D8%AB%D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A5%D8%B6%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9

- ↑ https://www.noonpost.org/content/6533

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Al-Haj, Ahmed (26 March 2015). "Saudi Arabia launches airstrikes in Yemen, targeting rebel-held military installations". Associated Press. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Senegal to send 2,100 troops to join Saudi-led alliance". Reuters. 4 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ Hearst, David (13 March 2017). "EXCLUSIVE: Pakistan sends combat troops to southern Saudi border". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "SOMALIA: Somalia finally pledges support to Saudi-led coalition in Yemen – Raxanreeb Online". RBC Radio. 7 April 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- 1 2 Ricks, Thomas E. (11 January 2016). "What Would a Saudi-Iran War Look Like? Don't look now, but it is already here". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ Hussain, Tom (17 April 2015). "Pakistan agrees to send ships to block arms shipments to Yemen rebels". McClatchyDC. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Ritzinger, Louis (27 April 2015). "Why Pakistan Is Staying Out of Yemen". National Interest. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ (in Turkish) "Dışişleri Bakanlığı, Husi terörüne karşı Yemen'e destek verdi". Türkiye. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ "Breaking Yemen's Stalemate". Stratfor. 29 March 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ↑ http://www.yemenface.net/%D9%86%D8%B5%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%88%D8%AB%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%82-%D8%A5%D8%B3%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%8A%D9%84-%D8%AA%D8%B4%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%83-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B9%D9%88/

- ↑ Bowen, Jeremy (7 July 2014). "The fearsome Iraqi militia vowing to vanquish Isis". BBC News. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ http://www.alkawthartv.com/news/102095

- ↑ https://english.alahednews.com.lb/25957/547

- ↑ http://www.alkawthartv.com/news/86262

- ↑ Pileggi, Tamar (15 March 2016). "Iran denies top general called Saudi, not Israel, its enemy". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ "Iran Guards head calls Saudi Arabia 'terrorist state'". The Times of Israel. 4 July 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia, Zionist regime behind resignation of Lebanese PM". Mehr News Agency. 5 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2018/08/285117.htm

- ↑ http://ansaar-alwalaey.com/الولائي-يدين-الاعتداءات-الجبانة-من-ال/

- ↑ http://web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/629

- ↑ "PROFILE: New Saudi Interior Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Saud bin Nayef". Al Arabiya English. 21 June 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ Frantzman, Seth J. (8 November 2017). "Riyadh's 'anti-Hezbollah minister'". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ "تعيين المقدم عبيد فاضل الشمري بدلًا من السهيان" (in Arabic). Alweeam.com.sa. 15 December 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ Tawfeeq, Mohammed (27 February 2018). "Saudi Arabia replaces military commanders in late-night reshuffle". CNN. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ "BDF Commander-in-Chief meets new Joint Peninsula Shield Forces Commander". Bahrain News Agency. 21 May 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ Narayan, Chandrika (5 November 2017). "Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigns". CNN. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ Karam, Zeina (4 November 2017). "Lebanon's prime minister just resigned 'over plot to target his life'". The Independent. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ Henderson, Simon (21 February 2014). "Saudi Arabia's Domestic and Foreign Intelligence Challenges". Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ Lippman, Thomas W. (16 April 2014). "Saudi Intel Chief Prince Bandar Is Out, But Is He Really Out?". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ Al Saeri, Muqbil (March 2011). "A talk with Peninsula Shield force commander Mutlaq bin Salem Al Azima". Asharq Al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 29 March 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- 1 2 Bronner, Ethan; Slackman, Michael (14 March 2011). "Saudi Troops Enter Bahrain to Help Put Down Unrest". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- 1 2 Fitch, Asa (6 November 2017). "Iran-Saudi Cold War Intensifies as Militant Threat Fades". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- 1 2 Gause III, F. Gregory (July 2014). "Beyond Sectarianism: The New Middle East Cold War" (PDF). Brookings Doha Center Analysis Paper. Brookings Institution (11): 1, 3. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Rubin, Jennifer (6 January 2016). "The Iran-Saudi Arabia proxy war". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ Gerges, Fawaz (15 December 2013). "Saudi Arabia and Iran must end their proxy war in Syria". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ Rogin, Josh (4 November 2015). "Iran and Saudi Arabia Clash Inside Syria Talks". Bloomberg View. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

...Iran and Saudi Arabia to discuss anything civilly, much less come to an agreement on Syria, where both sides have proxy forces in the fight.

- ↑ Loewenstein, Jennifer (2 October 2015). "Heading Toward a Collision: Syria, Saudi Arabia and Regional Proxy Wars". CounterPunch. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

Saudi Arabian and Iranian-backed factions are contributing to the proxy war in Syria...

- ↑ Tisdall, Simon (25 March 2015). "Iran-Saudi proxy war in Yemen explodes into region-wide crisis". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ↑ Browning, Noah (21 April 2015). "The Iran-Saudi Arabia proxy war in Yemen has reached a new phase". Business Insider. Reuters. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ↑ Rubin, Alissa J. (6 July 2016). "Iraq Before the War: A Fractured, Pent-Up Society". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ↑ Mabon, Simon. "The Battle for Bahrain: Iranian-Saudi Rivalry". Middle East Policy Council. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ↑ Ghattas, Kim (20 May 2016). "Iran-Saudi tensions simmer in Lebanon". BBC News. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ Kenyon, Peter (17 June 2017). "Qatar's Crisis With Saudi Arabia And Gulf Neighbors Has Decades-Long Roots". NPR. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ Panda, Ankit (22 January 2016). "Why Is Pakistan Interested in Brokering Peace Between Iran and Saudi Arabia?". The Diplomat. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ↑ Sewag, Zulqarnain (30 April 2015). "Sectarian Rise in Pakistan: Role of Saudi Arabia and Iran". 1 (3) – via www.gjms.co.in.

- ↑ Seerat, Rustam Ali (14 January 2016). "Iran and Saudi Arabia in Afghanistan". The Diplomat. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 Mir, Haroun (6 April 2015). "Afghanistan stuck between Iran and Saudi Arabia". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ Thurston, Alex (31 October 2016). "How far does Saudi Arabia's influence go? Look at Nigeria". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- 1 2 Oladipo, Tomi (7 January 2016). "Saudi Arabia and Iran fight for Africa's loyalty". BBC News. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ "Morocco severs ties with Iran over support for West Sahara Polisario front: official". Reuters. 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ El Harmouzi, Nouh. "Repercussions of the Saudi-Iranian Conflict on North Africa". The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Shankar, Abha (6 October 2016). "The Saudi-Iran Rivalry and Sectarian Strife in South Asia". The Diplomat. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ Peyrouse, Sebastien (6 April 2014). "Iran's Growing Role in Central Asia? Geopolitical, Economic and Political Profit and Loss Account". Al Jazeera Center for Studies. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ Dorsey, James (19 February 2018). "Expanding Regional Rivalries: Saudi Arabia and Iran battle it out in Azerbaijan". International Policy Digest. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ↑ See:

- Koelbl, Susanne; Shafy, Samiha; Zand, Bernhard (9 May 2016). "Saudia Arabia Iran and the New Middle Eastern Cold War". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- Pollack, Kenneth M. (8 January 2016). "Fear and Loathing in Saudi Arabia". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- Ellis, Sam (17 July 2017). "The Middle East's cold war, explained". Vox. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Fathollah-Nejad, Ali (25 October 2017). "The Iranian–Saudi Hegemonic Rivalry". Belfer Center. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ↑ Klare, Michael (1 June 2013). "Welcome to Cold War II". Tom Dispatch. RealClearWorld. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Meyer, Henry; Wishart, Ian; Biryukov, Andrey (13 February 2016). "Russia's Medvedev: We Are in 'a New Cold War'". Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- 1 2 Simpson Jr., George L. (1 March 2010). "Russian and Chinese Support for Tehran". Middle East Quarterly. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- 1 2 Blanchard, Ben (16 November 2017). "China's Xi offers support for Saudi amid regional uncertainty". Reuters. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ Miglietta, John P. (2002). American Alliance Policy in the Middle East, 1945-1992: Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia. Lexington Books. p. 56. ISBN 0739103040.

- ↑ Ramazani, R.K. (1 March 1979). "Security in the Persian Gulf". Foreign Affairs (Spring 1979). Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ↑ Gold, Dore (2003). Hatred's Kingdom. Washington, DC: Regnery. pp. 75–6. ISBN 9780895260611.

- ↑ "The Sunni-Shia Divide". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Amiri, Reza Ekhtiari; Ku Hasnita Binti Ku Samsu; Hassan Gholipour Fereidouni (2011). "The Hajj and Iran's Foreign Policy towards Saudi Arabia". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 46 (678). Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Gaub, Florence (February 2016). "War of words: Saudi Arabia v Iran" (PDF). European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS). Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Wallace, Charles P. (3 August 1987). "Iran Asks Overthrow of Saudi Rulers Over Riots: Tehran Stand on Mecca Clash Adds to Tensions; Police Accused of Following U.S. Instructions". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Gibson, Bryan R. (2010). Covert Relationship: American Foreign Policy, Intelligence, and the Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988. ABC-CLIO. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9780313386107.

- ↑ Kinzer, Stephen (October 2008). "Inside Iran's Fury". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ↑ Bruno, Greg (13 October 2011). "State Sponsors: Iran". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ↑ Butt, Yousaf (21 January 2015). "How Saudi Wahhabism Is the Fountainhead of Islamist Terrorism". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ↑ Cockburn, Patrick (11 January 2016). "Prince Mohammed bin Salman: Naive, arrogant Saudi prince is playing with fire". The Independent. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ↑ Fahim, Kareem; Kirkpatrick, David D. (14 May 2012). "Saudi Arabia Seeks Union of Monarchies in Region". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Hammond, Andrew (17 May 2012). "Analysis: Saudi Gulf union plan stumbles as wary leaders seek detail". Reuters. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Ramani, Samuel (12 September 2016). "Israel Is Strengthening Its Ties With The Gulf Monarchies". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ "Turkey joins Sunni 'anti-terrorist' military coalition". Hurriyet Daily News. Agence France-Presse. 15 December 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ "What do Russia and Iran think about Saudi Arabia's coalition initiative?". Euronews. 15 December 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ Riedel, Bruce (2011). "Brezhnev in the Hejaz". The National Interest (September–October 2011). Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ Byman, Daniel (1 December 2011). "After the hope of the Arab Spring, the chill of an Arab Winter". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ Ross, Dennis (20 June 2017). "Trump Is on a Collision Course With Iran". Politico Magazine. Politico. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ Bazzi, Mohamad (20 June 2017). "The Growing U.S.-Iran Proxy Fight in Syria". The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ See:

- "Bahrain FM: Muslim Brotherhood is a terrorist group". Al Jazeera. 6 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Saudi Arabia declares Muslim Brotherhood 'terrorist group'". BBC News. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood declared 'terrorist group'". BBC News. 25 December 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "Resolution of the State Duma, 2 December 2003 N 3624-III GD "on the Application of the State Duma of the Russian Federation" on the suppression of the activities of terrorist organizations on the territory of the Russian Federation" (in Russian). Consultant Plus.

- Shahine, Alaa; Carey, Glen (9 March 2014). "U.A.E. Supports Saudi Arabia Against Qatar-Backed Brotherhood". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ Gause III, F. Gregory (27 June 2017). "What the Qatar crisis shows about the Middle East". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- 1 2 Al-Rasheed, Madawi (23 April 2018). "What Fuels the Saudi Rivalry With Iran?". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ Hossein Mousavian, Seyed (3 June 2016). "Saudi Arabia Is Iran's New National Security Threat". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ Farmanfarmaian, Roxane (15 November 2012). "Redrawing the Middle East map: Iran, Syria and the new Cold War". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ Hubbard, Ben (25 September 2015). "Hajj Tragedy Inflames Schisms During a Pilgrimage Designed for Unity". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan (24 September 2015). "How the deadly hajj stampede feeds into old Middle East rivalries". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Black, Ian; Weaver, Matthew (25 September 2015). "Iran blames Saudi leaders for hajj disaster as investigation begins". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Schemm, Paul (12 May 2016). "Iran suspends participation in the hajj as relations with Saudi Arabia plummet". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ "Saudi launches Persian hajj TV after tensions with Iran". Agence France‑Presse. 11 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ "Iran, Saudi spar over running of haj pilgrimage". Reuters. 6 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Brumfield, Ben; Basil, Yousuf; Pearson, Michael (2 January 2016). "Tehran protest after Saudi Arabia executes Shiite cleric". CNN. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ Loveluck, Louisa. "Iran supreme leader says Saudi faces 'divine revenge'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ "Police Arrest 40 People for Storming Saudi Embassy in Tehran". Fars News Agency. 3 January 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Brumfield, Ben; Basil, Yousuf; Pearson, Michael (3 January 2016). "Mideast protests rage after Saudi Arabia executes Shia cleric al-Nimr, 46 others". CNN. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ↑ "More countries back Saudi Arabia in Iran dispute". Al Jazeera. 6 January 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia ally Comoros breaks off relations with Iran". Agence France-Presse. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ "Bahrain cuts diplomatic ties with Iran". Al Jazeera. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Bennett-Jones, Owen (4 May 2015). "Saudi king faces changing landscape". BBC News. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ Stuster, J. Dana (13 September 2016). "Middle East Ticker: A New Syrian Ceasefire and a Saudi-Iran Oil Spat". Lawfare Blog. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Arkhipov, Ilya; Khrennikova, Dina; Mazneva, Elena (2 September 2016). "Putin Pushes for Oil Freeze Deal With OPEC, Exemption for Iran". Bloomberg. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ El Gamal, Rania; Zhdannikov, Dmitry (23 September 2016). "Saudis offer oil cut for OPEC deal if Iran freezes output: sources". Reuters. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ Khalilzad, Zalmay (14 September 2016). "'We Misled You': How the Saudis Are Coming Clean on Funding Terrorism". Politico Magazine. Politico. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Zarif, Mohammad Javad (13 September 2016). "Mohammad Javad Zarif: Let Us Rid the World of Wahhabism". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ O'Connor, Tom (24 November 2016). "Saudi Arabia vs. Iran: How Will Donald Trump Influence The Middle East Cold War?". International Business Times. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ Erdbrink, Thomas; Krauss, Clifford (8 December 2016). "Iran Races to Clinch Oil Deals Before Donald Trump Takes Office". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ Hubbard, Ben; Erdbrink, Thomas (21 May 2017). "In Saudi Arabia, Trump Reaches Out to Sunni Nations, at Iran's Expense". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ↑ "'You might get shot any time': Saudi forces raid Shia town as Riyadh welcomes Trump". RT. 19 May 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "Snipers Injure Scores of Civilians in Saudi Arabia's Qatif". Iran Front Page. 14 June 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ McKernan, Bethan (15 May 2017). "Two dead in Saudi town 'siege' against Shia militants". The Independent. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ MacDonald, Alex (14 May 2017). "Several reported killed as Saudi town enters fifth day of 'siege'". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi forces kill head of Quran council in Qatif". Press TV. 25 June 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi regime forces kill Sheikh Nimr's cousins in Qatif: Report". Press TV. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "U.N. slams erasing of "cultural heritage" in Saudi Arabia". Reuters. 24 May 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi coast guard's killing of Iranian fisherman unjustifiable: Qassemi". Press TV. 18 June 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Tehran says Saudi coastguard killed Iranian fisherman". Al Jazeera. 17 June 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ Al-Shihri, Abdullah; Batrawy, Aya (19 June 2017). "Saudi Arabia claims arrest of Iran's Revolutionary Guard". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Associated Press. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Iran denies Saudi claim of Revolutionary Guards' arrest". Al Jazeera. 19 June 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ Sharafedin, Bozorgmehr (7 June 2017). "Islamist militants strike heart of Tehran, Iran blames Saudis". Reuters. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia prime suspect in Tehran attacks: Iranian official". Press TV. 14 June 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ Karimi, Nasser (9 June 2017). "Iran leaders accuse US, Saudis of supporting Tehran attacks". Associated Press. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ Osborne, Samuel (13 June 2017). "US 'created Isis' and its war on the terrorists is 'a lie', says Iran's Supreme Leader". The Independent. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ Revill, John (25 October 2017). "Swiss to represent Iran, Saudi interests after rivals broke ties". Reuters. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, David D. (6 November 2017). "Saudi Arabia Charges Iran With 'Act of War,' Raising Threat of Military Clash". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ↑ El Sirgany, Sarah (7 November 2017). "Iran's actions may be 'act of war,' Saudi crown prince says". CNN. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Bahrain says pipeline explosion 'terrorist sabotage' linked to Iran". Deutsche Welle. 12 November 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ↑ "Dubai security chief calls for bombing of Al Jazeera". Al Jazeera. 25 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ O'Connor, Tom (27 November 2017). "Iran: Muslim 'Resistance' to U.S., Saudi Arabia and Israel Ready to Fight Worldwide". Newsweek. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ Carey, Glen (10 January 2018). "Even Saudi Arabia's Allies Are Questioning Its Mideast Power Plays". Bloomberg. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ↑ "Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, power behind the throne". BBC News. 7 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Perper, Rosie (7 March 2018). "Saudi Arabia is in nuclear talks with the US — and it could be a sign the country is trying to get even with rival Iran". Business Insider. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan (8 March 2018). "Saudi crown prince sees a new axis of 'evil' in the Middle East". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- 1 2 Hubbard, Ben (15 March 2018). "Saudi Crown Prince Likens Iran's Supreme Leader to Hitler". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Macias, Amanda (19 March 2018). "Saudi crown prince, Trump to hold 'critical' talks on Iran nuclear deal". CNBC. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ Chulov, Martin (24 October 2017). "I will return Saudi Arabia to moderate Islam, says crown prince". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Landler, Mark (8 May 2018). "Trump Withdraws U.S. From 'One-Sided' Iran Nuclear Deal". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ↑ Randolph, Eric (26 February 2018). "Iran's eastern shift shows patience running out with the West". Yahoo News. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ O'Connor, Tom (10 May 2018). "Saudi Arabia Should 'Come Out of the Closet' and Help Fight Iran in Syria, Israel Says". Newsweek. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ O'Connor, Tom (9 May 2018). "Did Trump Break the Law? U.S. Leaves Iran Deal, Violates World Order and Risks War, Experts Say". Newsweek. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Harris, Gardiner; Ewing, Jack (6 August 2018). "U.S. to Restore Sanctions on Iran, Deepening Divide With Europe". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ Bayoumy, Yara; Landay, Jonathan; Strobel, Warren (27 July 2018). "Trump seeks to revive 'Arab NATO' to confront Iran". Reuters. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ "Bahrain: Widespread Suppression, Scant Reforms". Human Rights Watch. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ Goulka, Jeremiah; Hansell, Lydia; Wilke, Elizabeth; Larson, Judith (2009). "The Mujahedin-e Khalq in Iraq: a policy conundrum" (PDF). RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-4701-4.

- ↑ Mousavian, Seyed Hossein (21 July 2016). "From Iran to Nice, We Must Confront All Terrorism to End Terrorism". Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Iranian Kurds Return to Arms". Stratfor. 29 July 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ↑ "Iran: Saudis gave Israel 'strategic' intel in 2006 Lebanon war". The Times of Israel. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ O'Connor, Tom (10 May 2018). "Saudi Arabia Should 'Come Out of the Closet' and Help Fight Iran in Syria, Israel Says". Newsweek. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Marcus, Jonathan (24 November 2017). "Israel and Saudi Arabia: What's shaping the covert 'alliance'". BBC News. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Hubbard, Ben (13 May 2018). "With Demise of Nuclear Deal, Iran's Foes See an Opportunity. Others See Risk of War". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Karami, Arash (2 August 2016). "Were Saudis behind Abbas-MEK meeting?". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Mohyeldin, Ayman (6 June 2017). "Qatar and Its Neighbors Have Been At Odds Since the Arab Spring". NBC News. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ↑ Wintour, Patrick (7 June 2017). "Qatar: UAE and Saudi Arabia step up pressure in diplomatic crisis". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ↑ Gambrell, Jon (6 June 2017). "Arab nations cut ties with Qatar in new Mideast crisis". Associated Press. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ↑ Browning, Noah (5 June 2017). "Yemen cuts diplomatic ties with Qatar: state news agency". Reuters. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Qatar row: Saudi and Egypt among countries to cut Doha links". BBC News. 5 June 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Khatri, Shabina S. (1 July 2017). "Defense minister: Blockade of Qatar a 'declaration of war'". Doha News. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Alkhalisi, Zahraa (22 June 2017). "Qatar: 'We can defend our currency and the economy'". CNN. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Fahim, Kareem (23 June 2017). "Demands by Saudi-led Arab states for Qatar include shuttering Al Jazeera". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ Erickson, Amanda (23 June 2017). "Why Saudi Arabia hates Al Jazeera so much". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi-led group: Qatar not serious about demands". Al Jazeera. 6 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi-led group vows 'appropriate' measures". Al Jazeera. 7 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "Qatar To Reinstate Ambassador To Iran Amid Gulf Crisis". 24 August 2017.

- ↑ "Syrian conflict: Russian bombers use Iran bases for air strikes". BBC News. 16 August 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Mullen, Jethro; Basil, Yousuf (28 September 2015). "Iraq agrees to share intelligence with Russia, Iran and Syria". CNN. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ Barnard, Anne; Shoumali, Karam (12 October 2015). "U.S. Weaponry Is Turning Syria Into a Proxy War With Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ Pengelly, Martin (4 October 2015). "John McCain says US is engaged in proxy war with Russia in Syria". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ Tilghman, Andrew; Pawlyk, Oriana (4 October 2015). "U.S. vs. Russia: What a war would look like between the world's most fearsome militaries". Military Times. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ O'Connor, Tom (19 January 2018). "China May Be the Biggest Winner of All If Assad Takes Over Syria". Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ↑ Buckley, Chris (26 February 2018). "Xi Jinping Thought Explained: A New Ideology for a New Era". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ Khalaji, Mehdi (27 June 2011). "Iran's Policy Confusion about Bahrain". The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ Johnson, Henry (30 October 2015). "Mapping the Deaths of Iranian Officers Across Syria". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Saul, Jonathan; Hafezi, Parisa (21 February 2014). "Iran boosts military support in Syria to bolster Assad". Reuters. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Sanger, David E.; Kirkpatrick, David D.; Sengupta, Somini (29 October 2015). "Rancor Between Saudi Arabia and Iran Threatens Talks on Syria". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Bassam, Laila; Perry, Tom (6 November 2015). "Saudi support to rebels slows Assad attacks: pro-Damascus sources". Reuters. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Reardon, Martin (26 March 2015). "Saudi Arabia, Iran and the 'Great Game' in Yemen". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Malsin, Jared. "Yemen Is the Latest Victim of the Increase in Iran-Saudi Arabia Tension". Time (11 January 2016). Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Landry, Carole (30 April 2015). "Iran arming Yemen's Huthi rebels since 2009: UN report". Yahoo News. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Schmitt, Eric; Worth, Robert F. (15 March 2012). "With Arms for Yemen Rebels, Iran Seeks Wider Mideast Role". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Bayoumy, Yara; Ghobari, Mohammed (15 December 2014). "Iranian support seen crucial for Yemen's Houthis". Reuters. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ See:

- "Exclusive: Iran Steps up Support for Houthis in Yemen's War – Sources". U.S. News & World Report. 21 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Arab coalition intercepts Houthi ballistic missile targeting Saudi city of Jazan". Al Arabiya English. 20 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Taleblu, Behnam Ben; Toumaj, Amir (21 August 2016). "Analysis: IRGC implicated in arming Yemeni Houthis with rockets". Long War Journal. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Segall, Michael (2 March 2017). "Yemen Has Become Iran's Testing Ground for New Weapons". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Exclusive: Iran steps up weapons supply to Yemen's Houthis via Oman – officials". Reuters. 20 October 2016.

- ↑ Miles, Tom (9 May 2015). "Saudi-led strikes in Yemen break international law: U.N. coordinator". Reuters. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Mazzetti, Mark; Hubbard, Ben; Rosenberg, Matthew (13 October 2016). "Yemen Sees U.S. Strikes as Evidence of Hidden Hand Behind Saudi Air War". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ Gaouette, Nicole (13 October 2016). "US in Yemen: If you threaten us, we'll respond". CNN. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ Fisher, Max (19 November 2016). "How the Iranian-Saudi Proxy Struggle Tore Apart the Middle East". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ↑ Gause III, F. Gregory (March 2007). "Saudi Arabia: Iraq, Iran, the Regional Power Balance, and the Sectarian Question" (PDF). Strategic Insights. 6 (2). Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Pfiffner, James P. (February 2010). "US Blunders in Iraq: De-Baathification and Disbanding the Army" (PDF). Intelligence and National Security. 25 (1). doi:10.1080/02684521003588120. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Milani, Mohsen (22 June 2014). "Tehran Doubles Down". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Foizee, Bahauddin (June 5, 2018). "ISIS resurgence more than likely in Iraq". Daily Times. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ↑ Foizee, Bahauddin (11 December 2016). "Iranian Influence Gives Saudi Arabia Heartburn". International Policy Digest. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Georgy, Michael; Aboulenein, Ahmed; Rasheed, Ahmed (21 March 2018). "In symbolic victory, Iran conquers Iraq's dates market". Reuters. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ Ibish, Hussein (4 October 2017). "The Gulf Arab Countries and the Kurdish Referendum". Stratfor.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia's use of soft power in Iraq is making Iran nervous". The Economist. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ "Former Saddam aide seeks to reshape Iraq's Sunni insurgency". Reuters. 10 April 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ↑ "Saddam's 'king of clubs' reappears on Baath anniversary". Rudaw. 8 April 2018.

- ↑ Haddad, Fanar (August 10, 2017). "Why a controversial Iraqi Shiite cleric visited Saudi Arabia". The Washington Post.