Homo

| Homo | |

|---|---|

| |

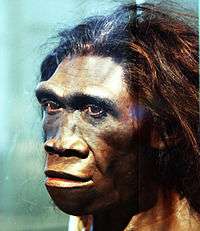

| Forensic reconstruction of an adult female Homo erectus[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Species | |

For other species or subspecies suggested, see below. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Synonyms

| |

Homo (Latin homō "human being") is the genus that encompasses the extant species Homo sapiens (modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely related to modern humans (depending on a species), most notably Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis. The genus is taken to emerge with the appearance of Homo habilis, just more than two million years ago.[2] Homo is derived from the genus Australopithecus, which itself had previously split from the lineage of Pan, the chimpanzees.[3] Taxonomically, Homo is the only genus assigned to the subtribe Hominina which, with the subtribes Australopithecina and Panina, comprise the tribe Hominini.

Homo erectus appeared about two million years ago and, in several early migrations, it spread throughout Africa (where it is dubbed Homo ergaster) and Eurasia. It was likely the first human species to live in a hunter-gatherer society and to control fire. An adaptive and successful species, Homo erectus persisted for more than a million years, and gradually diverged into new species by around 500,000 years ago[4].

Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) emerges close to 300,000 to 200,000 years ago,[5] most likely in Africa, and Homo neanderthalensis emerges at around the same time in Europe and Western Asia. H. sapiens dispersed from Africa in several waves, from possibly as early as 250,000 years ago, and certainly by 130,000 years ago, the so-called Southern Dispersal beginning about 70,000 years ago leading to the lasting colonisation of Eurasia and Oceania by 50,000 years ago. Both in Africa and Eurasia, H. sapiens met with and interbred with[6][7] archaic humans. Separate archaic (non-sapiens) human species are thought to have survived until around 40,000 years ago (Neanderthal extinction), with possible late survival of hybrid species as late as 12,000 years ago (Red Deer Cave people).

Among extant populations of Homo sapiens, the deepest temporal division is found in the San people of Southern Africa, estimated at close to 130,000 years.[8]

Names and taxonomy

- See Homininae for an overview of taxonomy.

The Latin noun homō (genitive hominis) means "human being" or "man" in the generic sense of "human being, mankind".[9] The binomial name Homo sapiens was coined by Carl Linnaeus (1758).[10] Names for other species of the genus were introduced beginning in the second half of the 19th century (H. neanderthalensis 1864, H. erectus 1892).

Even today, the genus Homo has not been properly defined.[11][12][13] Since the early human fossil record began to slowly emerge from the earth, the boundaries and definitions of the genus Homo have been poorly defined and constantly in flux. Because there was no reason to think it would ever have any additional members, Carl Linnaeus did not even bother to define Homo when he first created it for humans in the 18th century. The discovery of Neanderthal brought the first addition.

The genus Homo was given its taxonomic name to suggest that its member species can be classified as human. And, over the decades of the 20th century, fossil finds of pre-human and early human species from late Miocene and early Pliocene times produced a rich mix for debating classifications. There is continuing debate on delineating Homo from Australopithecus—or, indeed, delineating Homo from Pan, as one body of scientists argue that the two species of chimpanzee should be classed with genus Homo rather than Pan. Even so, classifying the fossils of Homo coincides with evidences of: 1) competent human bipedalism in Homo habilis inherited from the earlier Australopithecus of more than four million years ago, (see Laetoli); and 2) human tool culture having begun by 2.5 million years ago.

From the late-19th to mid-20th centuries, a number of new taxonomic names including new generic names were proposed for early human fossils; most have since been merged with Homo in recognition that Homo erectus was a single and singular species with a large geographic spread of early migrations. Many such names are now dubbed as "synonyms" with Homo, including Pithecanthropus,[14] Protanthropus,[15] Sinanthropus,[16] Cyphanthropus,[17] Africanthropus,[18] Telanthropus,[19] Atlanthropus,[20] and Tchadanthropus.[21]

Classifying the genus Homo into species and subspecies is subject to incomplete information and remains poorly done. This has led to using common names ("Neanderthal" and "Denisovan") in even scientific papers to avoid trinomial names or the ambiguity of classifying groups as incertae sedis (uncertain placement)—for example, H. neanderthalensis vs. H. sapiens neanderthalensis, or H. georgicus vs. H. erectus georgicus.[22] Some recently extinct species in the genus Homo are only recently discovered and do not as yet have consensus binomial names (see Denisova hominin and Red Deer Cave people).[23] Since the beginning of the Holocene, it is likely that Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) have been the only extant species of Homo.

John Edward Gray (1825) was an early advocate of classifying taxa by designating tribes and families.[24] Wood and Richmond (2000) proposed that Hominini ("hominins") be designated as a tribe that comprised all species of early humans and pre-humans ancestral to humans back to after the chimpanzee-human last common ancestor; and that Hominina be designated a subtribe of Hominini to include only the genus Homo—that is, not including the earlier upright walking hominins of the Pliocene such as Australopithecus, Orrorin tugenensis, Ardipithecus, or Sahelanthropus.[25] Designations alternative to Hominina existed, or were offered: Australopithecinae (Gregory & Hellman 1939) and Preanthropinae (Cela-Conde & Altaba 2002);[26][27][28] and later, Cela-Conde and Ayala (2003) proposed that the four genera Australopithecus, Ardipithecus, Praeanthropus, and Sahelanthropus be grouped with Homo within Hominina.[29]

Evolution

- See Hominini and Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor for the separation of Australopithecina and Panina.

Australopithecus

Several species, including Australopithecus garhi, Australopithecus sediba, Australopithecus africanus, and Australopithecus afarensis, have been proposed as the direct ancestor of the Homo lineage.[31][32] These species have morphological features that align them with Homo, but there is no consensus as to which gave rise to Homo.

Especially since the 2010s, the delineation of Homo from Australopithecus has become more contentious. Traditionally, the advent of Homo has been taken to coincide with the first use of stone tools (the Oldowan industry), and thus by definition with the beginning of the Lower Palaeolithic. But in 2010, evidence was presented that seems to attribute the use of stone tools to Australopithecus afarensis around 3.3 million years ago, close to a million years before the first appearance of Homo.[33] LD 350-1, a fossil mandible fragment dated to 2.8 Mya, discovered in 2015 in Afar, Ethiopia, was described as combining "primitive traits seen in early Australopithecus with derived morphology observed in later Homo.[34] Some authors would push the development of Homo close to or even past 3 Mya.[35] Others have voiced doubt as to whether Homo habilis should be included in Homo, proposing an origin of Homo with Homo erectus at roughly 1.9 Mya instead. [36]

The most salient physiological development between the earlier australopithecine species and Homo is the increase in endocranial volume (ECV), from about 460 cm3 (28 cu in) in A. garhi to 660 cm3 (40 cu in) in H. habilis and further to 760 cm3 (46 cu in) in H. erectus, 1,250 cm3 (76 cu in) in H. heidelbergensis and up to 1,760 cm3 (107 cu in) in H. neanderthalensis. However, a steady rise in cranial capacity is observed already in Autralopithecina and does not terminate after the emergence of Homo, so that it does not serve as an objective criterion to define the emergence of the genus.[37]

Homo habilis

Homo habilis emerged about 2.1 Mya. Already before 2010, there were suggestions that H. habilis should not be placed in genus Homo but rather in Australopithecus.[39][40] The main reason to include H. habilis in Homo, its undisputed tool use, has become obsolete with the discovery of Australopithecus tool use at least a million years before H. habilis.[33] Furthermore, H. habilis was long thought to be the ancestor of the more gracile Homo ergaster (Homo erectus). In 2007, it was discovered that H. habilis and H. erectus coexisted for a considerable time, suggesting that H. erectus is not immediately derived from H. habilis but instead from a common ancestor.[41] With the publication of Dmanisi skull 5 in 2013, it has become less certain that Asian H. erectus is a descendant of African H. ergaster which was in turn derived from H. habilis. Instead, H. ergaster and H. erectus appear to be variants of the same species, which may have originated in either Africa or Asia[42] and widely dispersed throughout Eurasia (including Europe, Indonesia, China) by 0.5 Mya.[43]

Homo erectus

Homo erectus has often been assumed to have developed anagenetically from Homo habilis from about 2 million years ago. This scenario was strengthened with the discovery of Homo erectus georgicus, early specimens of H. erectus found in the Caucasus, which seemed to exhibit transitional traits with H. habilis. As the earliest evidence for H. erectus was found outside of Africa, it was considered plausible that H. erectus developed in Eurasia and then migrated back to Africa. Based on fossils from the Koobi Fora Formation, east of Lake Turkana in Kenya, Spoor et al. (2007) argued that H. habilis may have survived beyond the emergence of H. erectus, so that the evolution of H. erectus would not have been anagenetically, and H. erectus would have existed alongside H. habilis for about half a million years (1.9 to 1.4 million years ago), during the early Calabrian.[44]

A separate South African species Homo gautengensis has been postulated as contemporary with Homo erectus in 2010.[45]

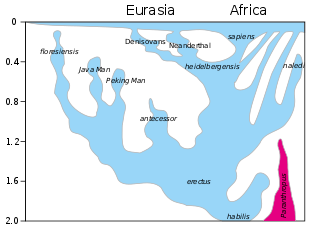

Cladogram

The cladogram below depicts most species of Homo, with Australopithecus as an outgroup, according to Strait, Fleagle and Grine (2015).[46]

| Hominina (4.5 Ma) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dispersal

By about 1.8 million years ago, Homo erectus is present in both East Africa (Homo ergaster) and in Western Asia (Homo georgicus). The ancestors of Indonesian Homo floresiensis may have left Africa even earlier.[47]

Homo erectus and related or derived archaic human species over the next 1.5 million years spread throughout Africa and Eurasia.[48] Europe is reached by about 0.5 Mya by Homo heidelbergensis.

Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens develop after about 300 kya. Homo naledi is present in Southern Africa by 300 kya.

H. sapiens soon after its first emergence spread throughout Africa, and to Western Asia in several waves, possibly as early as 250 kya, and certainly by 130 kya. Most notable is the Southern Dispersal of H. sapiens around 60 kya, which led to the lasting peopling of Oceania and Eurasia by anatomically modern humans.[49] H. sapiens interbred with archaic humans both in Africa and in Eurasia, in Eurasia notably with Neanderthals and Denisovans. [50]

Among extant populations of Homo sapiens, the deepest temporal division is found in the San people of Southern Africa, estimated at close to 130,000 years,[8] or possibly more than 300,000 years ago.[51] Temporal division among non-Africans is of the order of 60,000 years in the case of Australo-Melanesians. Division of Europeans and East Asians is of the order of 50,000 years, with repeated and significant admixture events throughout Eurasia during the Holocene.

Archaic human species may have survived until the beginning of the Holocene (Red Deer Cave people), although they were mostly extinct or absorbed by the expanding H. sapiens populations by 40 kya (Neanderthal extinction).

List of species

The species status of H. rudolfensis, H. ergaster, H. georgicus, H. antecessor, H. cepranensis, H. rhodesiensis, H. neanderthalensis, Denisova hominin, Red Deer Cave people, and H. floresiensis remains under debate. H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis are closely related to each other and have been considered to be subspecies of H. sapiens.

There has historically been a trend to postulate "new human species" based on as little as an individual fossil. A "minimalist" approach to human taxonomy recognizes at most three species, Homo habilis (2.1–1.5 Mya, membership in Homo questionable), Homo erectus (1.8–0.1 Mya, including the majority of the age of the genus, and the majority of archaic varieties as subspecies,[52] including H. heidelbergensis as a late or transitional variety[53]) and Homo sapiens (300 kya to present, including H. neanderthalensis and other varieties as subspecies).

| Species | Temporal range kya | Habitat | Adult height | Adult mass | Cranial capacity (cm³) | Fossil record | Discovery / publication of name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. habilis membership in Homo uncertain |

2,100 – 1,500[54] | East Africa | 110-140 cm (4 ft 11 in) | 33–55 kg (73–121 lb) | 510–660 | Many | 1960/1964 |

| H. rudolfensis membership in Homo uncertain |

1,900 | Kenya | 700 | 2 sites | 1972/1986 | ||

| H. gautengensis also classified as H. habilis |

1,900 – 600 | South Africa | 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) | 3 individuals[55] | 2010/2010 | ||

| H. erectus | 1,900 – 140 | Africa, Eurasia | 180 cm (5 ft 11 in) | 60 kg (130 lb) | 850 (early) – 1,100 (late) | Many[59] | 1891/1892 |

| H. ergaster African H. erectus |

1,800 – 1,300[60] | East and Southern Africa | 700–850 | Many | 1949/1975 | ||

| H. antecessor also classified as H. heidelbergensis |

1,200 – 800 | Western Europe | 175 cm (5 ft 9 in) | 90 kg (200 lb) | 1,000 | 2 sites | 1994/1997 |

| H. heidelbergensis | 600 – 300[61] | Europe, Africa | 180 cm (5 ft 11 in) | 90 kg (200 lb) | 1,100–1,400 | Many | 1907/1908 |

| H. cepranensis a single fossil, possibly H. erectus |

c. 450[62] | Italy | 1,000 | 1 skull cap | 1994/2003 | ||

| H. rhodesiensis also classified as H. heidelbergensis or a subspecies of H. sapiens |

c. 300 | Zambia | 1,300 | single or very few | 1921/1921 | ||

| H. naledi |

c. 300[63] | South Africa | 150 cm (4 ft 11 in) | 45 kg (99 lb) | 450 | 15 individuals | 2013/2015 |

| H. sapiens (anatomically modern humans) |

300[64] – present | Worldwide | 150 - 190 cm (4 ft 7 in - 6 ft 3 in) | 50–100 kg (110–220 lb) | 950–1,800 | (extant) | —/1758 |

| H. neanderthalensis possibly a subspecies of H. sapiens |

240 – 40[65] | Europe, Western Asia | 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) | 55–70 kg (121–154 lb) (heavily built) | 1,200–1,900 | Many | 1829/1864 |

| H. floresiensis classification uncertain |

190 – 50 | Indonesia | 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) | 25 kg (55 lb) | 400 | 7 individuals | 2003/2004 |

| H. tsaichangensis possibly H. erectus |

c. 100[66] | Taiwan | 1 individual | 2008(?)/2015 | |||

| Denisova hominin possible H. sapiens subspecies or hybrid |

40 | Siberia | 1 site | 2000/2010[67] | |||

| Red Deer Cave people possible H. sapiens subspecies or hybrid |

15–12[68] | Southwest China | Very few | 2012/— |

See also

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

- Nature timeline

References

- ↑ Reconstruction by John Gurche (2010), Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, based on KNM ER 3733 and 992. Abigail Tucker, "A Closer Look at Evolutionary Faces", Smithsonian.com, 25 February 2010. H. erectus has the most extensive range of all species of Homo, from 1.8 to 0.14 Mya, or some 80% of the entire lifetime of the genus.

- ↑ The conventional estimate on the age of H. habilis is at roughly 2.1 to 2.3 million years. Stringer, C.B. (1994). "Evolution of early humans". In Steve Jones, Robert Martin & David Pilbeam (eds.). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 242. Friedemann Schrenk, Ottmar Kullmer, Timothy Bromage, "The Earliest Putative Homo Fossils", chapter 9 in: Winfried Henke, Ian Tattersall (eds.), Handbook of Paleoanthropology, 2007, pp 1611–1631, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_52. Suggestions for pushing back the age to 2.8 Mya were made in 2015 based on the discovery of a jawbone: Spoor, Fred; Gunz, Philipp; Neubauer, Simon; Stelzer, Stefanie; Scott, Nadia; Kwekason, Amandus; Dean, M. Christopher (March 5, 2015). "Reconstructed Homo habilis type OH 7 suggests deep-rooted species diversity in early Homo". Nature. 519 (7541): 83–86. Bibcode:2015Natur.519...83S. doi:10.1038/nature14224. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 25739632. .

- ↑ Schuster, Angela M. H. (1997). "Earliest Remains of Genus Homo". Archaeology. 50 (1). Retrieved 5 March 2015. The line to the earliest members of Homo were derived from Australopithecus, a genus which had separated from the Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor by late Miocene or early Pliocene times.

- ↑ H. erectus in the narrow sense (the Asian species) was extinct by 140,000 years ago, Homo erectus soloensis, found in Java, is considered the latest known survival of H. erectus. Formerly dated to as late as 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, a 2011 study pushed back the date of its extinction of H. e. soloensis to 143,000 years ago at the latest, more likely before 550,000 years ago. Indriati E, Swisher CC III, Lepre C, Quinn RL, Suriyanto RA, et al. 2011 The Age of the 20 Meter Solo River Terrace, Java, Indonesia and the Survival of Homo erectus in Asia.PLoS ONE 6(6): e21562. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021562.

- ↑ Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ Green, R.E.; Krause, J.; Briggs, A.W.; Maricic, T.; Stenzel, U.; Kircher, M.; Patterson, N.; Li, H.; Zhai, W.; Fritz, M.H.Y.; Hansen, N.F. (2010). "A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome". Science. 328 (5979): 710–722. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..710G. doi:10.1126/science.1188021. PMC 5100745. PMID 20448178.

- ↑ Lowery, R.K.; Uribe, G.; Jimenez, E.B.; Weiss, M.A.; Herrera, K.J.; Regueiro, M.; Herrera, R.J. (2013). "Neanderthal and Denisova genetic affinities with contemporary humans: Introgression versus common ancestral polymorphisms". Gene. 530 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.005. PMID 23872234. This study raises the possibility of observed genetic affinities between archaic and modern human populations being mostly due to common ancestral polymorphisms.

- 1 2 Henn, Brenna; Gignoux, Christopher R.; Jobin, Matthew (2011). "Hunter-gatherer genomic diversity suggests a southern African origin for modern humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences. 108 (13): 5154–62. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5154H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017511108. PMC 3069156. PMID 21383195.

- ↑ The word "human" itself is from Latin humanus, an adjective formed on the root of homo, thought to derive from a Proto-Indo-European word for "earth" reconstructed as *dhǵhem-. dhghem The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000.

- ↑ Linné, Carl von (1758). Systema naturæ. Regnum animale (10 ed.). pp. 18, 20. Retrieved 19 November 2012. . Note: In 1959, Linnaeus was designated as the lectotype for Homo sapiens (Stearn, W. T. 1959. "The background of Linnaeus's contributions to the nomenclature and methods of systematic biology", Systematic Zoology 8 (1): 4-22, p. 4) which means that following the nomenclatural rules, Homo sapiens was validly defined as the animal species to which Linnaeus belonged.

- ↑ Schwartz, Jeffrey H.; Tattersall, Ian (28 August 2015). "Defining the genus Homo". Science. 349 (6251): 931–932. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..931S. doi:10.1126/science.aac6182. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ Lents, Nathan (4 October 2014). "Homo naledi and the Problems with the Homo Genus". The Wildernist. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ Wood, B.; Collard, M. (2 April 1999). "The human genus". Science. 284 (5411): 65–71. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.65. PMID 10102822.

- ↑ "ape-man", from Pithecanthropus erectus (Java Man), Eugène Dubois, Pithecanthropus erectus : eine menschenähnliche Übergangsform aus Java (1894), identified with the Pithecanthropus alalus (i.e. "non-speaking ape-man") hypothesized earlier by Ernst Haeckel

- ↑ "early man", Protanthropus primigenius Ernst Haeckel, Systematische Phylogenie vol. 3 (1895), p. 625

- ↑ "Sinic man", from Sinanthropus pekinensis (Peking Man), Davidson Black (1927).

- ↑ "crooked man", from Cyphanthropus rhodesiensis (Rhodesian Man) William Plane Pycraft (1928).

- ↑ "African man", used by T. F. Dreyer (1935) for the Florisbad Skull he found in 1932 (also Homo florisbadensis or Homo helmei). Also the genus suggested for a number of archaic human skulls found at Lake Eyasi by Weinert (1938). Leaky, Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society' (1942), p. 43.

- ↑ "remote man"; from Telanthropus capensis (Broom and Robinson 1949), see (1961), p. 487.

- ↑ from Atlanthropus mauritanicus, name given to the species of fossils (three lower jaw bones and a parietal bone of a skull) discovered in 1954 to 1955 by Camille Arambourg in Tighennif, Algeria. Arambourg, C. (1955). "A recent discovery in human paleontology: Atlanthropus of ternifine (Algeria)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 13 (2): 191–201. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330130203.

- ↑ Y. Coppens, "L'Hominien du Tchad", Actes V Congr. PPEC I (1965), 329f.; "Le Tchadanthropus", Anthropologia 70 (1966), 5–16.

- ↑ Alexandra Vivelo (2013), Characterization of Unique Features of the Denisovan Exome Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Barras, Colin (2012-03-14). "Chinese human fossils unlike any known species". New Scientist. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- ↑ J. E. Gray, "An outline of an attempt at the disposition of Mammalia into Tribes and Families, with a list of genera apparently appertaining to each Tribe", Annals of Philosophy', new series (1825), pp. 337–344.

- ↑ Wood and Richmond; Richmond, BG (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (Pt 1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270.

- ↑ Brunet, M.; et al. (2002). "A new hominid from the upper Miocene of Chad, central Africa". Nature. 418: 145–151. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880.

- ↑ Cela-Conde, C.J.; Ayala, F.J. (2003). "Genera of the human lineage". PNAS. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC 164648. PMID 12794185.

- ↑ Wood, B.; Lonergan, N. (2008). "The hominin fossil record: taxa, grades and clades" (PDF). J. Anat. 212: 354–376. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00871.x. PMC 2409102. PMID 18380861.

- ↑ Cela-Conde, C. J.; Ayala, F. J. (2003). "Genera of the human lineage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC 164648. PMID 12794185.

- ↑ Reconstruction by John Gurche (2010),Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Abigail Tucker, "A Closer Look at Evolutionary Faces", Smithsonian.com, February 25, 2010.

- ↑ Pickering, R.; Dirks, P. H.; Jinnah, Z.; De Ruiter, D. J.; Churchill, S. E.; Herries, A. I.; Berger, L. R. (2011). "Australopithecus sediba at 1.977 Ma and implications for the origins of the genus Homo". Science. 333 (6048): 1421–1423. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1421P. doi:10.1126/science.1203697. PMID 21903808.

- ↑ Asfaw, B.; White, T.; Lovejoy, O.; Latimer, B.; Simpson, S.; Suwa, G. (1999). "Australopithecus garhi: a new species of early hominid from Ethiopia". Science. 284 (5414): 629–635. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..629A. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.629. PMID 10213683.

- 1 2 McPherron, S. P.; Alemseged, Z.; Marean, C. W.; Wynn, J. G.; Reed, D.; Geraads, D.; Bobe, R.; Bearat, H. A. (2010). "Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia". Nature. 466: 857–860. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..857M. doi:10.1038/nature09248. PMID 20703305. "The oldest direct evidence of stone tool manufacture comes from Gona (Ethiopia) and dates to between 2.6 and 2.5 million years (Myr) ago. [...] Here we report stone-tool-inflicted marks on bones found during recent survey work in Dikika, Ethiopia [... showing] unambiguous stone-tool cut marks for flesh removal [..., dated] to between 3.42 and 3.24 Myr ago [...] Our discovery extends by approximately 800,000 years the antiquity of stone tools and of stone-tool-assisted consumption of ungulates by hominins; furthermore, this behaviour can now be attributed to Australopithecus afarensis."

- ↑ Villmoare, Brian; Kimbel, William H.; Seyoum, Chalachew; Campisano, Christopher J.; DiMaggio, Erin N.; Rowan, John; Braun, David R.; Arrowsmith, J. Ramón; Reed, Kaye E. (2015-03-20). "Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–1355. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1352V. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25739410. . See also: Erin N. DiMaggio EN; Campisano CJ; Rowan J; Dupont-Nivet G; Deino AL; et al. (2015). "Late Pliocene fossiliferous sedimentary record and the environmental context of early Homo from Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347: 1355–1359. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1355D. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1415. PMID 25739409.

- ↑ Cela-Conde and Ayala (2003) recognize five genera within Hominina: Ardipithecus, Australopithecus (including Paranthropus), Homo (including Kenyanthropus), Praeanthropus (including Orrorin), and Sahelanthropus. Cela-Conde, C. J.; Ayala, F. J. (2003). "Genera of the human lineage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC 164648. PMID 12794185.

- ↑ "the adaptive coherence of Homo would be compromised if H. habilis is included in Homo. Thus, if these arguments are accepted the origins of the genus Homo are coincident in time and place with the emergence of H. erectus, not H. habilis" Bernard Wood, "Did early Homomigrate 'out of' or 'in to' Africa?", PNAS vol. 108, no.26 (28 June 2011), 10375–10376.

- ↑ " A fresh look at brain size, hand morphology and earliest technology suggests that a number of key Homo attributes may already be present in generalized species of Australopithecus, and that adaptive distinctions in Homo are simply amplifications or extensions of ancient hominin trends. [...] the adaptive shift represented by the ECV of Australopithecus is at least as significant as the one represented by the ECV of early Homo, and that a major ‘grade-level’ leap in brain size with the advent of H. erectus is probably illusory" William H. Kimbel, Brian Villmoare, "From Australopithecus to Homo: the transition that wasn't", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 13 June 2016, DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0248.

- ↑ by W. Schnaubelt & N. Kieser (Atelier WILD LIFE ART); see Westfalen_in_der-Alt-und_Mittelsteinzeit, Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, Münster (2013), fig. 42.

- ↑ Wood and Richmond; Richmond, BG (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (Pt 1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270. p. 41: "A recent reassessment of cladistic and functional evidence concluded that there are few, if any, grounds for retaining H. habilis in Homo, and recommended that the material be transferred (or, for some, returned) to Australopithecus (Wood & Collard, 1999)."

- ↑ Miller J.M.A. (2000). "Craniofacial variation in Homo habilis: an analysis of the evidence for multiple species". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 112 (1): 103–128. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200005)112:1<103::AID-AJPA10>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 10766947.

- ↑ F. Spoor; M. G. Leakey; P. N. Gathogo; F. H. Brown; S. C. Antón; I. McDougall; C. Kiarie; F. K. Manthi; L. N. Leakey (2007-08-09). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..688S. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323. F. Spoor; M. G. Leakey; P. N. Gathogo; F. H. Brown; S. C. Antón; I. McDougall; C. Kiarie; F. K. Manthi; L. N. Leakey (2007-08-09). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..688S. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323. "A partial maxilla assigned to H. habilis reliably demonstrates that this species survived until later than previously recognized, making an anagenetic relationship with H. erectus unlikely"

- ↑ Augusti, Jordi; Lordkipanidze, David (June 2011). "How "African" was the early human dispersal out of Africa?". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (11–12): 1338–1342. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.1338A. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.012.

- ↑ Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana; McBride, Bunny (2007). Evolution and prehistory: the human challenge. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-495-38190-7. .

- ↑ "A partial maxilla assigned to H. habilis reliably demonstrates that this species survived until later than previously recognized, making an anagenetic relationship with H. erectus unlikely. The discovery of a particularly small calvaria of H. erectus indicates that this taxon overlapped in size with H. habilis, and may have shown marked sexual dimorphism. The new fossils confirm the distinctiveness of H. habilis and H. erectus, independently of overall cranial size, and suggest that these two early taxa were living broadly sympatrically in the same lake basin for almost half a million years." Spoor, F; Leakey, M.G; Gathogo, P.N; Brown, F.H; Antón, S.C; McDougall, I; Kiarie, C; Manthi, F.K.; Leakey, L.N. (2007). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..688S. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323.

- ↑ Curnoe, D (2010). "A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.)". HOMO – Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 61: 151–177. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002.

- ↑ Strait, David; Grine, Frederick; Fleagle, John (2015-01-01). Analyzing Hominin Hominin Phylogeny: Cladistic Approach. pp. 1989–2014 (cladogram p. 2006). ISBN 9783642399787. .

- ↑ In a 2015 phylogenetic study, H. floresiensis was placed with Australopithecus sediba, Homo habilis and Dmanisi Man, raising the possibility that the ancestors of Homo floresiensis left Africa before the appearance of Homo erectus, possibly even becoming the first hominins to do so and evolved further in Asia. Dembo, M., Matzke, N. J., Mooers, A. Ø. and Collard, M. (2015). "Bayesian analysis of a morphological supermatrix sheds light on controversial fossil hominin relationships" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0943. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ https://www.nature.com/news/oldest-ancient-human-dna-details-dawn-of-neanderthals-1.19557

- ↑ Green, RE; Krause, J; et al. (2010). "A draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome". Science. 328 (5979): 710–22. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..710G. doi:10.1126/science.1188021. PMC 5100745. PMID 20448178.

- ↑ Reich, D; Green, RE; Kircher, M; et al. (December 2010). "(December 2010). "Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia"". Nature. 468 (7327): 1053–60. Bibcode:2010Natur.468.1053R. doi:10.1038/nature09710. PMC 4306417. PMID 21179161. Reich; et al. (October 2011). "Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into southeast Asia and Oceania". Am J Hum Genet. 89 (4): 516–28. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005. PMC 3188841. PMID 21944045.

- ↑ Schlebusch; et al. (3 November 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652&ndash, 655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266.

- ↑ Skull suggests three early human species were one : Nature News & Comment David Lordkipanidze, Marcia S. Ponce de Leòn, Ann Margvelashvili, Yoel Rak, G. Philip Rightmire, Abesalom Vekua, Christoph P. E. Zollikofer (18 October 2013). "A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo". Science. 342 (6156): 326–331. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..326L. doi:10.1126/science.1238484. Switek, Brian (17 October 2013). "Beautiful Skull Spurs Debate on Human History". National Geographic. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis - The evolutionary dividing line between Homo erectus and modern humans was not sharp". Dennis O'Neil. Retrieved November 29, 2015. "Is Homo heidelbergensis a distinct species? New insight on the Mauer mandible". researchgate net. Retrieved November 29, 2015. "The evolution and development of cranial form" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Department of Anthropology Harvard University. 99: 1134–1139. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.1134L. doi:10.1073/pnas.022440799. PMC 122156. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ Confirmed H. habilis fossils are dated to between 2.1 and 1.5 million years ago. This date range overlaps with the emergence of Homo erectus. Schrenk, Friedemann; Kullmer, Ottmar; Bromage, Timothy (2007). "The Earliest Putative Homo Fossils". In Henke, Winfried; Tattersall, Ian. Handbook of Paleoanthropology. 1. In collaboration with Thorolf Hardt. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 1611–1631. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_52. ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4. DiMaggio, Erin N.; Campisano, Christopher J.; Rowan, John; et al. (March 20, 2015). "Late Pliocene fossiliferous sedimentary record and the environmental context of early Homo from Afar, Ethiopia". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 347 (6228): 1355–1359. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1355D. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1415. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25739409. Hominins with "proto-Homo" traits may have lived as early as 2.8 million years ago, as suggested by a fossil jawbone classified as transitional between Australopithecus and Homo discovered in 2015.

- ↑ Curnoe, Darren (June 2010). "A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.)". HOMO - Journal of Comparative Human Biology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 61 (3): 151–177. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002. ISSN 0018-442X. PMID 20466364. A species proposed in 2010 based on the fossil remains of three individuals dated between 1.9 and 0.6 million years ago. The same fossils were also classified as H. habilis, H. ergaster or Australopithecus by other anthropologists.

- ↑ Haviland, William A.; Walrath, Dana; Prins, Harald E. L.; McBride, Bunny (2007). Evolution and Prehistory: The Human Challenge (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-495-38190-7. H. erectus may have appeared some 2 million years ago. Fossils dated to as much as 1.8 million years ago have been found both in Africa and in Southeast Asia, and the oldest fossils by a narrow margin (1.85 to 1.77 million years ago) were found in the Caucasus, so that it is unclear whether H. erectus emerged in Africa and migrated to Eurasia, or if, conversely, it evolved in Eurasia and migrated back to Africa.

- ↑ Ferring, R.; Oms, O.; Agusti, J.; Berna, F.; Nioradze, M.; Shelia, T.; Tappen, M.; Vekua, A.; Zhvania, D.; Lordkipanidze, D. (2011). "Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (26): 10432. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810432F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108. PMC 3127884. PMID 21646521. Homo erectus soloensis, found in Java, is considered the latest known survival of H. erectus.

- ↑ Formerly dated to as late as 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, a 2011 study pushed back the date of its extinction of H. e. soloensis to 143,000 years ago at the latest, more likely before 550,000 years ago. Indriati E, Swisher CC III, Lepre C, Quinn RL, Suriyanto RA, et al. 2011 The Age of the 20 Meter Solo River Terrace, Java, Indonesia and the Survival of Homo erectus in Asia.PLoS ONE 6(6): e21562. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021562.

- ↑ Now also included in H. erectus are Peking Man (formerly Sinanthropus pekinensis) and Java Man (formerly Pithecanthropus erectus). H. erectus is now grouped into various subspecies, including Homo erectus erectus, Homo erectus yuanmouensis, Homo erectus lantianensis, Homo erectus nankinensis, Homo erectus pekinensis, Homo erectus palaeojavanicus, Homo erectus soloensis, Homo erectus tautavelensis, Homo erectus georgicus. The distinction from descendant species such as Homo ergaster, Homo floresiensis, Homo antecessor, Homo heidelbergensis and indeed Homo sapiens is not entirely clear.

- ↑ Hazarika, Manjil (2007). "Homo erectus/ergaster and Out of Africa: Recent Developments in Paleoanthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology" (PDF). EAA Summer School eBook. 1. European Anthropological Association. pp. 35–41. Retrieved 2015-05-04. "Intensive Course in Biological Anthrpology, 1st Summer School of the European Anthropological Association, 16–30 June, 2007, Prague, Czech Republic"

- ↑ The type fossil is Mauer 1, dated to ca. 0.6 million years ago. The transition from H. heidelbergensis to H. neanderthalensis between 300 and 243 thousand years ago is conventional, and makes use of the fact that there is no known fossil in this period. Examples of H. heidelbergensis are fossils found at Bilzingsleben (also classified as Homo erectus bilzingslebensis).

- ↑ Muttoni, Giovanni; Scardia, Giancarlo; Kent, Dennis V.; Swisher, Carl C.; Manzi, Giorgio (2009). "Pleistocene magnetochronology of early hominin sites at Ceprano and Fontana Ranuccio, Italy". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. ScienceDirect. 286: 255–268. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.286..255M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.06.032. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ Dirks, P.; et al. (9 May 2017). "The age of Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa". eLife. 6: e24231. doi:10.7554/eLife.24231.

- ↑ The age of H. sapiens has long been assumed to be close to 200,000 years, but since 2017 there have been a number of suggestions extending this time to has high as 300,000 years. In 2017, fossils found in Jebel Irhoud (Morocco) suggest that Homo sapiens may have speciated by as early as 315,000 years ago. Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017. Genetic evidence has been adduced for an age of roughly 270,000 years. Posth, Cosimo; et al. (4 July 2017). "Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals". Nature Communications. Bibcode:2017NatCo...816046P. doi:10.1038/ncomms16046. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ Bischoff, James L.; Shamp, Donald D.; Aramburu, Arantza; et al. (March 2003). "The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Th Equilibrium (>350 kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500 kyr: New Radiometric Dates". Journal of Archaeological Science. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 30 (3): 275–280. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0834. ISSN 0305-4403. The first humans with "proto-Neanderthal traits" lived in Eurasia as early as 0.6 to 0.35 million years ago (classified as H. heidelbergensis, also called a chronospecies because it represents a chronological grouping rather than being based on clear morphological distinctions from either H. erectus or H. neanderthalensis). There is a fossil gap in Europe between 300 and 243 kya, and by convention, fossils younger than 243 kya are called "Neanderthal". D. Dean; J.-J. Hublin; R. Holloway; R. Ziegler (1998). "On the phylogenetic position of the pre-Neandertal specimen from Reilingen, Germany". Journal of Human Evolution. 34 (5). pp. 485–508. doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0214.

- ↑ younger than 450 kya, either between 190-130 or between 70-10 kya. Chang, Chun-Hsiang; Kaifu, Yousuke; Takai, Masanaru; Kono, Reiko T.; Grün, Rainer; Matsu’ura, Shuji; Kinsley, Les; Lin, Liang-Kong (2015). "The first archaic Homo from Taiwan". Nature Communications. 6: 6037. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6E6037C. doi:10.1038/ncomms7037. PMC 4316746. PMID 25625212.

- ↑ provisional names Homo sp. Altai or Homo sapiens ssp. Denisova.

- ↑ Bølling-Allerød warming period; Curnoe, D.; et al. (2012). Caramelli, David, ed. "Human remains from the Pleistocene-Holocene transition of southwest China Suggest a complex evolutionary history for East Asians". PLoS ONE. 7 (3): e31918. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731918C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031918. PMC 3303470. PMID 22431968.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Homo |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Introduction to Paleoanthropology |

- Exploring the Hominid Fossil Record (Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology at George Washington University)

- Hominid species

- Prominent Hominid Fossils

- Mikko's Phylogeny archive

- Homo at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).