Venus figurines

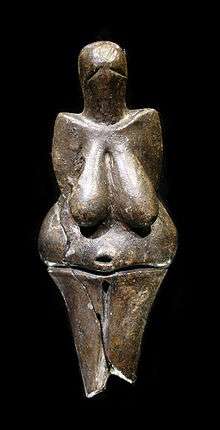

A Venus figurine is any Upper Paleolithic statuette portraying a woman,[1] although the fewer images depicting men or figures of uncertain sex,[2] and those in relief or engraved on rock or stones are often discussed together.[3] Most have been unearthed in Europe, but others have been found as far away as Siberia, extending their distribution across much of Eurasia, although with many gaps, such as the Mediterranean outside Italy.[4]

Most of them date from the Gravettian period (26,000–21,000 years ago),[3] but examples exist as early as the Venus of Hohle Fels, which dates back at least 35,000 years to the Aurignacian, and as late as the Venus of Monruz, from about 11,000 years ago in the Magdalenian. These figurines were carved from soft stone (such as steatite, calcite or limestone), bone or ivory, or formed of clay and fired. The latter are among the oldest ceramics known. In total, some 144 such figurines are known;[5] virtually all of modest size, between 3 cm and 40 cm or more in height.[1] They are some of the earliest works of prehistoric art.

Most of them have small heads, wide hips, and legs that taper to a point. Various figurines exaggerate the abdomen, hips, breasts, thighs, or vulva, although many do not, and the concentration in popular accounts on those that do reflects modern preoccupations rather than the range of actual artefacts. In contrast, arms and feet are often absent, and the head is usually small and faceless. Depictions of hairstyles can be detailed, and especially in Siberian examples, clothing or tattoos may be indicated.[6]

The original cultural meaning and purpose of these artifacts is not known. It has frequently been suggested that they may have served a ritual or symbolic function. There are widely varying and speculative interpretations of their use or meaning: they have been seen as religious figures,[7] as erotic art or sex aids,[8] or as self-depictions by female artists.[9]

Terminology

.jpg)

The expression 'Venus' was first used in the mid-nineteenth century by the Marquis de Vibraye, who discovered an important ivory figurine and named it La Vénus impudique or Venus Impudica ("immodest Venus"), contrasting it to the Venus Pudica, Hellenistic sculpture by Praxiteles showing Aphrodite covering her naked pubis with her right hand.[10]

The use of the name is metaphorical as there is no link between the figurines and the Roman goddess Venus, although they have been interpreted as representations of a primordial female goddess. The term has been criticised for being more a reflection of modern western ideas than reflecting the beliefs of the sculptures' original owners, but the name has persisted.[11]

History of discovery

Vénus impudique, the figurine that gave the whole class its name, was the very first Paleolithic sculptural representation of a woman discovered in modern times. It was found in about 1864 by Paul Hurault, 8th Marquis de Vibraye at the famous archaeological site of Laugerie-Basse in the Vézère valley (one of the many important Stone Age sites in and around the commune of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil in Dordogne, southwestern France). The Magdalenian "Venus" from Laugerie-Basse is headless, footless, armless but with a strongly incised vaginal opening.[12]

Four years later, Salomon Reinach published an article about a group of steatite figurines from the caves of Balzi Rossi. The famous Venus of Willendorf was excavated in 1908 in a loess deposit in the Danube valley, Austria. Since then, hundreds of similar figurines have been discovered from the Pyrenees to the plains of Siberia. They are collectively described as "Venus figurines" in reference to the Roman goddess of beauty, Venus, since the prehistorians of the early 20th century assumed they represented an ancient ideal of beauty. Early discourse on "Venus figurines" was preoccupied with identifying the race being represented and the steatopygous fascination of Saartjie Baartman, the "Hottentot Venus" exhibited as a living ethnographic curiosity to connoisseurs in Paris early in the nineteenth century.[13]

In September 2008, archaeologists from the University of Tübingen discovered a 6 cm figurine woman carved from a mammoth's tusk, the Venus of Hohle Fels, dated to at least 35,000 years ago, representing the earliest known sculpture of this type, and the earliest known work of figurative art altogether. The ivory carving, found in six fragments in Germany's Hohle Fels cave, represents the typical features of Venus figurines, including the swollen belly, wide-set thighs, and large breasts.[14][15]

Description

The majority of the Venus figurines appear to be depictions of women, many of which follow certain artistic conventions, on the lines of schematisation and stylisation. Most of them are roughly lozenge-shaped, with two tapering terminals at top (head) and bottom (legs) and the widest point in the middle (hips/belly). In some examples, certain parts of the human anatomy are exaggerated: abdomen, hips, breasts, thighs, vulva. In contrast, other anatomical details are neglected or absent, especially arms and feet. The heads are often of relatively small size and devoid of detail. Some may represent pregnant women, while others show no such signs.[17] It has been suggested that aspects of the typical depiction and perspective, such as the large and often pendulous breasts, emphasis on the upper rather than lower buttocks, and lack of feet and faces, support the theory that these are self-portraits by women without access to mirrors, looking at their own bodies.[18] The absence of feet has led to suggestions that the figures might have been made to stand upright by inserting the legs into the ground like a peg.

The high amount of fat around the buttocks of some of the figurines has led to numerous interpretations. The issue was first raised by Édouard Piette, excavator of the Brassempouy figure and of several other examples from the Pyrenees. Some authors saw this feature as the depiction of an actual physical property, resembling (but not depicting) the Khoisan tribe of southern Africa, while others interpreted it as a symbol of fertility and abundance.

Recently, similar figurines with protruding buttocks from the prehistoric Jōmon period Japan were also interpreted as steatopygia of local women, possibly under nutritional stress.[19] (c.f.Jōmon Venus)

The Venus of Willendorf and the Venus of Laussel bear traces of having been externally covered in red ochre. The significance of this is not clear, but is normally assumed to be religious or ritual in nature—perhaps symbolic of the blood of menstruation or childbirth. Some buried human bodies were similarly covered, and the colour may just represent life.[20]

All generally accepted Paleolithic female figurines are from the Upper Palaeolithic. Although they were originally mostly considered Aurignacian, the majority are now associated with the Gravettian and Solutrean.[4] In these periods, the more rotund figurines are predominant. During the Magdalenian, the forms become finer with more detail; conventional stylization also develops.

Notable specimens

| Name | Age (kyr, approx.) | Location | Material | |

| Venus of Hohle Fels | 35–40 | Swabian Alb, Germany | mammoth ivory | |

| Venus of Galgenberg | 30 | Lower Austria | serpentine rock | |

| Venus of Dolní Věstonice | 27–31 | Moravia, Czech Republic | ceramic | |

| Venus of Lespugue | 24–26 | French Pyrenees | ivory | |

| Venus of Willendorf | 24–26 | Lower Austria | limestone | |

| Venus of Brassempouy | 23 | Brassempouy, France | ivory | |

| Venus of Petřkovice | 23 | Silesia, Czech Republic | hematite | |

| Venus figurines of Mal'ta | 23 | Irkutsk Oblast, Russia | ivory | |

| Venuses of Buret' | 23 | Irkutsk Oblast, Russia | ivory, serpentine rock | |

| Venus of Moravany | 23 | Moravany nad Váhom, Slovakia | mammoth ivory | |

| Venus of Savignano | 20–25 | Savignano sul Panaro, Italy | serpentine rock | |

| Venus figurines of Balzi Rossi | 18–25 | Ventimiglia, Italy | ivory, soapstone, serpentine, chlorite | |

| Venus figurines of Gönnersdorf | 11,5–15 | Germany | ivory, antler, bone | |

| Venus figurines of Petersfels | 11,5–15 | Engen, Germany | black jet | |

| Venus of Monruz | 11 | Switzerland | black jet | |

| Venus of Parabita | 12–14 | Parabita, Italy | horse bone | |

Classification

A number of attempts to subdivide or classify the figurines have been made.[21] One of the less controversial is that by Henri Delporte, simply based on geographic provenance.[22] He distinguishes:

- the Venus figurines of the Pyrenees-Aquitaine group (Venus of Lespugue, of Laussel and of Brassempouy)

- the Venus figurines of the Italian group (Venus of Savignano and of Balzi Rossi)

- the Venus figurines of the Rhine-Danube group (Venus of Willendorf and of Dolní Věstonice)

- the Venus figurines of the Russian group (Kostienki and Zaraysk[23][24] in Russia and Gagarino in Ukraine)

- the Venus figurines of the Siberian group (Mal'ta Venus, Bouret' Venus).

According to André Leroi-Gourhan, there are cultural connections between all these groups. He states that certain anatomical details suggest a shared Oriental origin, followed by a westward diffusion.[25]

Interpretation

There are many interpretations of the figurines, often based on little argument or fact.[3]

Like many prehistoric artifacts, the cultural meaning of these figures may never be known. Archaeologists speculate, however, that they may be emblems of security and success, fertility icons, or direct representations of a mother goddess. The female figures, as part of Upper Palaeolithic portable art, appear to have no practical use in the context of subsistence. They are mostly discovered in settlement contexts, both in open-air sites and caves;[3] burial contexts are much rarer.

At Gagarino in Russia, seven Venus figurines were found in a hut of 5 m diameter; they have been interpreted as apotropaic amulets, connected with the occupants of the dwelling. At Mal'ta, near Lake Baikal in Siberia, figurines are only known from the left sides of huts. The figurines were probably not hidden or secret amulets, but rather were displayed to be seen by all (a factor that may explain their wide geographic spread). An image of excess weight may have symbolized a yearning for plenty and security.

Helen Benigni argues in The Emergence of the Goddess that the consistency in design of these featureless, large-breasted, often pregnant figures throughout a wide region and over a long period of time suggests they represent an archetype of a female Supreme Creator. Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age people likely connected the female as a creator innately tied to the cycles of nature: women were commonly believed to give birth and their menstrual cycles aligned with lunar cycles and tides.[26]

Later female figurines and continuity

Some scholars and popular theorists suggest a direct continuity between the Palaeolithic female figurines and later examples of female depictions from the Neolithic or even the Bronze Age.[27] Such views have been contested on numerous grounds, not least the general absence of such depictions during the intervening Mesolithic.

A female figurine which has 'no practical use and is portable' and has the common elements of a Venus figurine (a strong accent or exaggeration of female sex linked traits, and the lack of complete lower limbs) may be considered to be a Venus figurine, even if from after the main Palaeolithic period. Figurines which match this definition, apart from date, have been found in the Neolithic and into the Bronze Age. The period and location that a figurine came from will contribute to the opinion of a given archeologist, such that ceramic figurines from the late ceramic Neolithic may be accepted as Venus figurines, while stone figurines from later periods are not. This is a matter of ongoing debate given the strong similarity between many figurines from the Palaeolithic, Neolithic and beyond. A reworked endocast of a brachiopod from around 6000 BC in Norway has been identified as a late Venus figurine.[28]

This means that a given female figurine may or may not be classified as a Venus figure by any given archeologist, regardless of its date, though most archaeologists disqualify figurines which date from after the Paleolithic, even though their purpose could have been the same. For instance, the Mehrgarh figurine has all of the common characteristics of a venus stone figurine, including large breasts and incomplete legs, however it came from what is now Pakistan and also dates to 3000 BCE, which lies after the beginning of the Bronze Age.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Fagan, 740

- ↑ Beck, 203

- 1 2 3 4 Fagan, 740-741

- 1 2 Fagan, 740-741; Beck, 203

- ↑ Cook

- ↑ Fagan, 740-741; Isabella, Jude, interview with April Nowell. "Palaeo-porn": we’ve got it all wrong, 2012. New Scientist, 216, Issue 2890, online; Cook; Beck, 205-214

- ↑ Beck, 207-208

- ↑ Rudgley, Richard, The Lost Civilizations of the Stone Age, 2000, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0684862700, 9780684862705194-198, google books; Fagan, 740-741

- ↑ William Haviland, Harald Prins, Dana Walrath, Bunny McBride, Anthropology: The Human Challenge, 13th edition, 2010, Cengage Learning, ISBN 0495810843, 9780495810841,google books; Cook; Beck, 205-208

- ↑ Beck, 202-203

- ↑ Dr. Beth Harris & Dr. Steven Zucker (27 May 2012). Nude Woman (Venus of Willendorf), c. 28,000-25,000 B.C.E. (youtube video). Smarthistory, Art History at Khan Academy. Event occurs at 0:21. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ↑ White, Randall (December 2008). "The Women of Brassempouy: A Century of Research and Interpretation" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 13 (4): 250–303. doi:10.1007/s10816-006-9023-z.

- ↑ Of the mammoth-ivory figurine fragment known as La Poire ("the pear") from her massive thighs, Randall White (White 2006:263, caption to fig. 6) observed the connection.

- ↑ Conard, Nicholas J (14 May 2009). "A female figurine from the basal Aurignacian of Hohle Fels Cave in southwestern Germany" (PDF). Nature. 459 (7244): 248–252. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..248C. doi:10.1038/nature07995. PMID 19444215. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ↑ Cressey, Daniel (13 May 2009). "Ancient Venus rewrites history books". Nature. News. doi:10.1038/news.2009.473.

- ↑ The body used is the local loess, with only traces of clay; there is no trace of surface burnishing or applied pigment. Pamela B. Vandiver, Olga Soffer, Bohuslav Klima and Jiři Svoboda, "The Origins of Ceramic Technology at Dolni Věstonice, Czechoslovakia", Science, New Series, 246, No. 4933 (November 24, 1989:1002-1008).

- ↑ Sandars, 29; Fagan, 740-741; Cook; Beck, 203-213, who analyses attempts to classify the figures.

- ↑ Cook; McDermott, LeRoy. 1996. "Self-representation in Upper Paleolithic Female Figurines". Current Anthropology 37 (2). [University of Chicago Press, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research]: 227–75. JSTOR

- ↑ Hudson MJ, et al. (2008). "Possible steatopygia in prehistoric central Japan: evidence from clay figurines". Anthropological Science. 116 (1): 87–92. doi:10.1537/ase.060317.

- ↑ Sandars, 28

- ↑ Beck, 208-213 analyses several

- ↑ H. Delporte : L’image de la femme dans l’art préhistorique, Éd. Picard (1993) ISBN 2-7084-0440-7

- ↑ Hizri Amirkhanov and Sergey Lev. New finds of art objects from the Upper Palaeolithic site of Zaraysk, Russia

- ↑ Membrana.ru, Венеры каменного века найдены под Зарайском

- ↑ Leroi-Gourhan, A., Cronología del arte paleolítico, 1966, Actas de VI Congreso internacional de Ciencias prehistóricas y protohistóricas, Roma.

- ↑ Benigni, Helen, ed. 2013. The Mythology of Venus: Ancient Calendars and Archaeoastronomy. Lanham, Maryland : University Press Of America.

- ↑ Walter Burkert, Homo Necans (1972) 1983:78, with extensive bibliography, including P.J. Ucko, who contested the identification with mother goddesses and argues for a plurality of meanings, in Anthropomorphic Figurines of Predynastic Egypt and Neolithic Crete with Comparative Material from the Prehistoric Near East and Mainland Greece (1968).

- ↑ Tidemann, Grethe. "Venus fra Svinesund". Uniforum. University of Oslo. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

References

- Beck, Margaret, in Ratman, Alison E. (ed.), Reading the Body: Representations and Remains in the Archaeological Record, 2000, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0812217098, 9780812217094, google books

- Cook, Jill, Venus figurines, Video with Dr Jill Cook, Curator of European Prehistory, British Museum

- Fagan, Brian M., Beck, Charlotte, "Venus Figurines", The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, 1996, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195076184, 9780195076189, google books

- Sandars, Nancy K. (1968), Prehistoric Art in Europe. Penguin: Pelican, now Yale, History of Art. (nb 1st ed.)

Further reading

- Abramova, Z., 1962: Paleolitičeskoe iskusstvo na territorii SSSR, Moskva : Akad. Nauk SSSR, Inst. Archeologii, 1962

- Abramova, Z., 1995: L'Art paléolithique d'Europe orientale et de Sibérie., Grenoble: Jérôme Millon.

- Cohen, C. : La femme des origines - images de la femme dans la préhistoire occidentale, Belin - Herscher (2003) ISBN 2-7335-0336-7

- Conard N., 2009: A female figurine from the basal Aurignacian deposits of Hohle Fels Cave in southwestern Germany. Nature, 2009; 459 (7244): 248 DOI: 10.1038/nature07995

- Cook, Jill 2013. Ice Age Art: the Arrival of the Modern Mind; London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2333-2

- Delporte, Henri 1993. L'image de la femme dans l'art préhistorique, éd. Picard. ( ISBN 2-7084-0440-7)

- Dixson, Alan F., and Barnaby Dixson. 2011. “Venus Figurines of the European Paleolithic: Symbols of Fertility or Attractiveness?” Journal of Anthropology 2011 [sic]: 1-11.

- Gvozdover, M., 1995: Art of the mammoth hunters: the finds from Avdeevo, (Oxbow Monograph 49), Oxford: Oxbow.

- Schlesier, Karl H. 2001. “More on the ‘Venus’ Figurines.” Current Anthropology 42: 410-12.

- Soffer O., Adovasio J., Hyland D., 2000: The 'Venus' Figurines - Textiles, Basketry, Gender, and Status in the Upper * Paleolithic, Current Anthropology Volume 41, Number 4, August–October 2000

- Rau, S., Naumann D., Barth M., Mühleis Y., Bleckmann C., 2009: Eiszeit: Kunst und Kultur, Thorbecke, 2009, 396p. ISBN 978-3-7995-0833-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Venus figurines. |