Homo erectus

| Homo erectus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton of Tautavel Man[2] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. erectus |

| Binomial name | |

| Homo erectus (Mayr 1950) | |

| Synonyms | |

Homo erectus (meaning "upright man") is a species of archaic humans that lived throughout most of the Pleistocene geological epoch. Its earliest fossil evidence dates to 1.8 million years ago (discovered 1991 in Dmanisi, Georgia).[5]

A debate regarding the classification, ancestry, and progeny of H. erectus, especially in relation to Homo ergaster, is ongoing, with two major positions:

- 1) H. erectus is the same species as H. ergaster, and thereby H. erectus is a direct ancestor of the later hominins including Homo heidelbergensis, Homo antecessor, Homo neanderthalensis, Homo Denisova, and Homo sapiens; or,

- 2) it is in fact an Asian species or subspecies distinct from African H. ergaster.[6]

Some paleoanthropologists consider H. ergaster to be a variety, that is, the "African" variety, of H. erectus; the labels "Homo erectus sensu stricto" (strict sense) for the Asian species and "Homo erectus sensu lato" (broad sense) have been offered for the greater species comprising both Asian and African populations.[7][8]

H. erectus was never extinct, but developed into derived species, notably Homo heidelbergensis. As a chronospecies, the time of its disappearance is thus a matter of convention. The species name proposed in 1950 defines Java Man as the type specimen (now H. e. erectus). Since then, there has been a trend in palaeoanthropology of reducing the number of proposed species of Homo, to the point where H. erectus includes all early (Lower Paleolithic) forms of Homo sufficiently derived from H. habilis and distinct from early H. heidelbergensis (in Africa also known as H. rhodesiensis).[9] In this wider sense, H. erectus had mostly been replaced by H. heidelbergensis by about 500,000 years ago, with possible late survival in Java as late as 140,000 years ago.[1] The discovery of the morphologically divergent Dmanisi skull 5 in 2013 has reinforced the trend of subsuming fossils formerly given separate species names under H. erectus considered as a wide-ranging, polymorphous species.[10] Thus, H. ergaster is now well within the accepted morphological range of H. erectus, and it has been suggested that even H. rudolfensis and H. habilis (alternatively suggested as late forms of Australopithecus rather than early Homo) should be considered early varieties of H. erectus.[11][12]

Discovery and type specimen

The Dutch anatomist Eugène Dubois, inspired by Darwin's theory of evolution as it applied to humanity, set out in 1886 for Asia (despite Darwin's theory of African origin) to find a human ancestor. In 1891, his team discovered a human fossil on the island of Java, Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Excavated from the bank of the Solo River at Trinil, in East Java, he named the species Pithecanthropus erectus—from the Greek πίθηκος,píthēkos "ape", and ἄνθρωπος ánthrōpos "human"—based on a skullcap (calotte) and a femur like that of Homo sapiens.

Dubois' 1891 find was the first fossil of a Homo-species (or any hominin species) found as result of a directed expedition and search (the first recognized human fossil had been the circumstantial discovery of Homo neanderthalensis in 1856; see List of human evolution fossils). The Java fossil from Indonesia aroused much public interest. It was dubbed by the popular press as Java Man; but few scientists accepted Dubois' argument that his fossil was the transitional form—the so-called "missing link"—between humans and nonhuman apes.[13]

Most of the spectacular discoveries of H. erectus next took place at the Zhoukoudian Project, now known as the Peking Man site, in Zhoukoudian, China. This site was first discovered by Johan Gunnar Andersson in 1921[14] and was first excavated in 1921, and produced two human teeth.[15] Davidson Black's initial description (1921) of a lower molar as belonging to a previously unknown species (which he named Sinanthropus pekinensis)[16] prompted widely publicized interest. Extensive excavations followed, which altogether uncovered 200 human fossils from more than 40 individuals including five nearly complete skullcaps.[17] Franz Weidenreich provided much of the detailed description of this material in several monographs published in the journal Palaeontologica Sinica (Series D).

Nearly all of the original specimens were lost during World War II; however, authentic casts were made by Weidenreich, which exist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, and are considered to be reliable evidence.

Similarities between Java Man and Peking Man led Ernst Mayr to rename both Homo erectus in 1950.

Throughout much of the 20th century, anthropologists debated the role of H. erectus in human evolution. Early in the century, due in part to the discoveries at Java and Zhoukoudian, the belief that modern humans first evolved in Asia was widely accepted. A few naturalists—Charles Darwin most prominent among them—theorized that humans' earliest ancestors were African: Darwin pointed out that chimpanzees and gorillas, humans' closest relatives, evolved and exist only in Africa.[18]

Origin and dispersal

The derivation of the genus Homo from Australopithecina took place in East Africa after 3 million years ago. The inclusion of species dated to just before 2 million years ago, Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis, into Homo is somewhat contentious.[19] Especially as H. habilis appears to have coexisted with H. ergaster/erectus for a substantial period after 2 Mya, it has been proposed that ergaster may not be directly derived from habilis.[20]

Homo erectus emerges about 2 million years ago. Fossils dated close to 1.8 million years ago have been found both in Africa and in West Asia, so this is unclear whether H. erectus emerged in Africa or in Asia. Ferring et al. (2011) suggest that it was still H. habilis that reached West Asia, and that early H. erectus developed there. Early H. erectus would then have dispersed from West Asia, to East Asia (Peking Man) Southeast Asia (Java Man), back to Africa (Homo ergaster), and to Europe (Tautavel Man).[21][22]

Africa

In the 1950s, archaeologists John T. Robinson and Robert Broom named Telanthropus capensis;[23] Robinson had discovered a jaw fragment in 1949 in Swartkrans, South Africa. Later, Simonetta proposed to re-designate it to Homo erectus, and Robinson agreed.[24]

From the 1950s forward, numerous finds in East Africa suggested sympatric coexistence for H. ergaster and H. habilis for several hundred millenia, which tends to confirm the hypothesis that they represent separate lineages from a common ancestor; that is, the ancestral relationship between them was not anagenetic, but was cladogenetic, which here suggests that a subgroup population of H. habilis—or of a common ancestor of H. habilis and H. ergaster/erectus—became reproductively isolated from the main-group population, eventually evolving into the new species Homo ergaster (Homo erectus sensu lato).[25]

In 1961, Yves Coppens discovered a skull in northern Chad. He coined the name Tchadanthropus uxoris for what he considered the earliest fossil human discovered in north Africa.[26] Although once considered to be a specimen of H. habilis,[27] T. uxoris has been subsumed into H. erectus but it is no longer considered a valid taxon.[26][28] It was reported that the fossil "had been so eroded by wind-blown sand that it mimicked the appearance of an australopith, a primitive type of hominid".[29] It is probably only 10,000 years old according to stratigraphy, paleontology and C14 dating presented in Michel Servant's PhD as early as 1973.[30]

Eurasia

Caucasus

Homo erectus georgicus is the subspecies name assigned to fossil skulls and jaws found in Dmanisi, Georgia. First proposed as a separate species, it is now classified within H. erectus.[31][32][33] The site was discovered in 1991 by Georgian scientist David Lordkipanidze. Five skulls were excavated from 1991 forward, including a "very complete" skull in 2005. Excavations at Dmanisi have yielded 73 stone tools for cutting and chopping and 34 bone fragments from unidentified fauna.[34]

After their initial assessment, some scientists were persuaded to name the Dmanisi find as a new species, Homo georgicus, which they posited as a descendant of African Homo habilis and an ancestor to Asian Homo erectus. This classification, however, was not supported, and the fossil was instead designated a divergent subgroup of Homo erectus.[35][36][37][38]

The fossil skeletons present a species primitive in its skull and upper body but with relatively advanced spine and lower limbs, implying greater mobility than the previous morphology.[39] It is now thought not to be a separate species, but to represent a stage soon after the transition between H. habilis to H. erectus; it has been dated at 1.8 Mya.[32][40] The assemblage includes one of the largest Pleistocene Homo mandibles (D2600), one of the smallest Lower Pleistocene mandibles (D211), a nearly complete sub-adult (D2735), and a toothless specimen D3444/D3900.[41]

Two of the skulls—D2700, with a brain volume of 600 cubic centimetres (37 cu in), and D4500 or Dmanisi Skull 5, with a brain volume of about 546 centimetres—present the two smallest and most primitive Hominina skulls from the Pleistocene period.[11] The variation in these skulls were compared to variations in modern humans and within a sample group of chimpanzees. The researchers found that, despite appearances, the variations in the Dmanisi skulls were no greater than those seen among modern people and among chimpanzees. These findings suggest that previous fossil finds that were classified as different species on the basis of the large morphological variation among them—including Homo rudolfensis, Homo gautengensis, H. ergaster, and potentially even H. habilis—should perhaps be re-classified to the same lineage as Homo erectus.[42]

East and Southeast Asia

H. erectus is attested with certainty in East and Southeast Asia from about 0.7 Ma, with possible early presence before 1 Ma; Stone tools from Shangchen discovered in 2018 were even claimed to be older than 2 Mya.[43]

Meganthropus refers to a group of fossils found in Java, dated to between 1.4 and 0.9 Mya, which are tentatively grouped with H. erectus, at least in the wider sense of the term in which "all earlier Homo populations that are sufficiently derived from African early Homo belong to H. erectus",[9] althogh in older literature has placed the fossils outside of Homo altogether.[44]

Java Man (H. e. erectus, the type specimen for H. erectus), discovered on the island of Java in 1891/2, is dated to 1.0–0.7 Mya. Lantian Man (H. e. lantianensis), discovered in 1963 in Lantian County, Shaanxi province, China, is roughly contemporary with Java Man.

Peking Man (H. e. pekinensis), discovered in 1923–27 at Zhoukoudian (Chou K'ou-tien) near Beijing, China, dates to about 0.75 Mya.[45] and a new 26Al/10Be dating suggests they are in the range of 680,000–780,000 years old.[46] Yuanmou Man (H. e. yuanmouensis), discovered in Yuanmou County in Yunnan, China, in 1965, is likely of similar age as Peking Man (but with dates proposed as early as 1.7 Mya).[47]

Nanjing Man (H. e. nankinensis), discovered in 1993 in the Hulu cave on the Tangshan hills near Nanjing, dates to about 0.6 Mya.[48]

Solo Man (H. e. soloensis), discovered between 1931/1933 along the Solo River, Java, is of uncertain age, dated between 0.55 and 0.14 Mya (the younger date would qualify Solo Man as the latest fossil still classified as H. erectus, even though it shows some derived features, notably larger cranial capacity).[49]

Europe

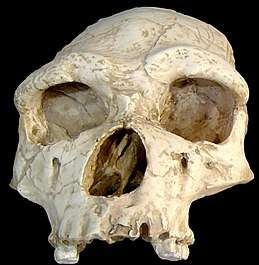

It is conventional to label European archaic humans contemporary with late H. erectus under the separate species name of Homo heidelbergensis, the immediate predecessor of Homo neanderthalensis. H. heidelbergensis fossils are recorded from 600 ka (Mauer 1 mandible), the oldest complete skulls are "Tautavel Man" (Homo erectus tautavelensis), c. 450 ka, and the Atapuerca skull ("Miguelón"), c. 430 ka. The oldest known human fossils found in Europe is a molar from the Sima del Elefante site, Atapuerca Mountains, Spain, dated c. 1.2 Mya. This is associated with the skull fragments of the "Boy of Gran Dolina" found nearby, dated 0.9 Mya and classified as Homo antecessor by the discoverers. The relationship of these fossils to H. erectus is open to debate, as no complete skull has been found. H. e. bilzingslebenensis (Vlcek 1978) refers to skull fragments found at the Bilzingsleben site, Thuringia, Germany.

There is, however, indirect evidence of human presence in Europe as early as 1.6 Mya, in the form of stone tools discovered at Lézignan-la-Cèbe, France, in 2008.[50] Other stone tools found in France and thought to predate 1 Mya are from Chilhac, Haute-Loire) and from the Grotte du Vallonnet, near Menton. Human presence in Great Britain close to 1 Mya is established by stone tools and fossilized footprints found near Happisburgh, Norfolk.[51][52]

Taxonomy

Paleoanthropologists continue to debate the classification of Homo erectus and Homo ergaster as separate species. One school of thought suggests dropping the taxon Homo erectus and equating H. erectus with the archaic H. sapiens.[53][54][55][56] Another calls H. ergaster the direct African ancestor of H. erectus, proposing that erectus emigrated out of Africa to Asia while branching into a distinct species.[57] Some scholars dispense with the species name ergaster, making no distinction between such fossils as the Turkana Boy and Peking Man. Still, "Homo ergaster" has gained some acceptance as a valid taxon, and the two species are still usually defined as distinct African and Asian populations of the greater species H. erectus, that is, "Homo erectus sensu lato".

Some have insisted that Ernst Mayr's biological species definition cannot be used to test the above hypotheses—that is, that the two species might be considered the same. Alternatively, the amount of variation of cranial morphology between known specimens of H. erectus and H. ergaster can be compared to the same variation within an appropriate population of living primates (that is, one of similar geographical distribution or close evolutionary relationship), such that: if the amount of variation between H. erectus and H. ergaster is greater than that within an appropriately selected population, for example, say, macaques, then H. erectus and H. ergaster may be considered as two different species.

Finding an extant (i.e., living) model suitable for field study, analysis, and comparison is very important; and selecting a living sample population of an appropriate species can be difficult. (For example, the morphological variation among the global population of H. sapiens is small,[58] so our own species diversity may not be a trustworthy comparison. Fossils found in Dmanisi, Georgia were originally designated as a separate (but closely related) species; but subsequent specimens showed their variation to be within the range of Homo erectus. and they are now classified as Homo erectus georgicus.) New foot tracks found in 2009 in Kenya and reported in Science by Matthew Bennett of Bournemouth University in Britain and his colleagues, confirmed that the gait of Homo erectus was heel-to-toe, walking as a modern human does, rather than with the australopithecine-like method of its own ancestors.[59]

H. erectus fossils show a cranial capacity greater than that of Homo habilis (although the Dmanisi specimens have distinctively small crania): the earliest fossils show a cranial capacity of 850 cm³, while later Javan specimens measure up to 1100 cm³,[58] overlapping that of H. sapiens.; the frontal bone is less sloped and the dental arcade smaller than that of the australopithecines; the face is more orthognatic (less protrusive) than either the australopithecines or H. habilis, with large brow-ridges and less prominent zygomata (cheekbones). The early hominins stood about 1.79 m (5 ft 10 in)[60]—only 17 percent of modern male humans are taller[61]—and were extraordinarily slender, with long arms and legs.[62]

Sexual dimorphism in H. erectus—males are about 25% larger than females—is slightly greater than seen in the later H. sapiens, but less than that of the earlier genus Australopithecus. Regarding evolution of human physiology, the discovery of the skeleton of "Turkana boy" (Homo ergaster) near Lake Turkana, Kenya, by Richard Leakey and Kamoya Kimeu in 1984—one of the most complete hominin skeletons ever discovered—has contributed greatly to the interpretation.

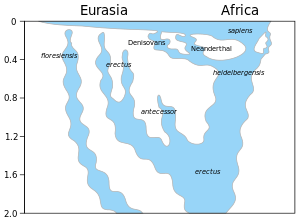

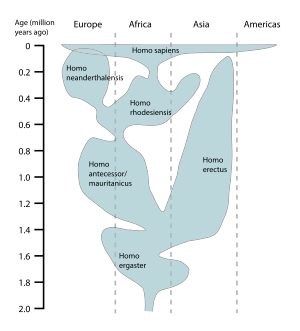

Stringer (2003, 2012) and Reed, et al. (2004) and others have produced schematic graph-models for interpreting the evolution of Homo sapiens from earlier species of Homo, including Homo erectus and/or Homo ergaster, see graphs at right. Blue areas denote the existence of one or more hominin species at a given time and place (that is, region). These and other interpretations differ mainly in the taxonomy and geographical distribution of species.[63][64]

Stringer (see upper graph-model) depicts the presence of H. erectus as dominating the temporal and geographic development of human evolution; and as persisting broadly throughout Africa and Eurasia for nearly 2 million years, eventually evolving into H. heidelbergensis / H. rhodesiensis, which in turn evolved into H. sapiens. Reed, et al. shows Homo ergaster as the ancestor of Homo erectus; then it is ergaster, or a variety of ergaster, or perhaps a hybrid of ergaster and erectus, which develops into species that evolve into archaic and then modern humans and then out of Africa.

Both models show the Asian variety of Homo erectus going extinct recently. And both models indicate species admixture: early modern humans spread from Africa across different regions of the globe and interbred with earlier descendants of H. heidelbergensis / H. rhodesiensis, namely the Neanderthals, Denisovans, as well as unknown archaic African hominins. See admixture; and see Neanderthal admixture theory.[65]

Behaviour

Tool use

The Paleolithic Age (Old Stone Age) of prehistoric human history and industry is dated from 2.6 million years ago to about 10,000 years ago;[66] thus it closely coincides with the Pleistocene epoch of geologic time, which is 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago.[67] The beginning of early human evolution reaches back to the earliest innovations of primitive technology and tool culture. H. erectus were the first to use fire to cook and to make hand axes out of stone.

Homo ergaster used more diverse and sophisticated stone tools than its predecessors, where early Homo erectus used comparatively primitive tools. This is probably because H. ergaster inherited, used, and created tools first of Oldowan technology and later advanced the technology to the Acheulean.[68] Because the use of Acheulean tools began ca. 1.8 million years ago,[69] and the line of H. erectus diverged some 200,000 years before the general innovation of Acheulean industry in Africa, then it is plausible that the Asian migratory descendants of H. erectus made no use of Acheulean technology. It has been suggested that the Asian H. erectus may have been the first humans to use rafts to travel over bodies of water, including oceans.[70] And the oldest stone tool found in Turkey reveals that hominins passed through the Anatolian gateway from western Asia to Europe approximately 1.2 million years ago—much earlier than previously thought.[71]

Use of fire

East African sites, such as Chesowanja near Lake Baringo, Koobi Fora, and Olorgesailie in Kenya, show potential evidence that fire was utilized by early humans. At Chesowanja, archaeologists found fire-hardened clay fragments, dated to 1.42 M.Y.A.[72] Analysis showed that, in order to harden it, the clay must have been heated to about 400 °C (752 °F). At Koobi Fora, two sites show evidence of control of fire by Homo erectus at about 1.5 M.Y.A., with reddening of sediment associated with heating the material to 200–400 degrees Celsius (392–752 degrees Fahrenheit).[72] At a "hearth-like depression" at a site in Olorgesailie, Kenya, some microscopic charcoal was found—but that could have resulted from natural brush fires.[72]

In Gadeb, Ethiopia, fragments of welded tuff that appeared to have been burned, or scorched, were found alongside H. erectus–created Acheulean artifacts; but such re-firing of the rocks may have been caused by local volcanic activity.[72] In the Middle Awash River Valley, cone-shaped depressions of reddish clay were found that could have been created only by temperatures of 200 °C (392 °F) or greater. These features are thought to be burnt tree stumps such that the fire was likely away from a habitation site.[72] Burnt stones are found in the Awash Valley, but naturally burnt (volcanic) welded tuff is also found in the area.

A site at Bnot Ya'akov Bridge, Israel is reported to show evidence that H. erectus or H. ergaster controlled fire there between 790,000 and 690,000 years ago;[73] to date this claim has been widely accepted. Some evidence is found that H. erectus was controlling fire less than 250,000 years ago. Evidence also exists that H. erectus were cooking their food as early as 500,000 years ago.[74] Re-analysis of burnt bone fragments and plant ashes from the Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa, has been dubbed evidence supporting human control of fire there by 1 M.Y.A.[75]

There is archaeological evidence that Homo erectus cooked their food.[74]

Sociality

Homo erectus was probably the first hominin to live in a hunter-gatherer society, and anthropologists such as Richard Leakey believe that erectus was socially more like modern humans than the more Australopithecus-like species before it. Likewise, increased cranial capacity generally coincides with the more sophisticated tools occasionally found with fossils.

The discovery of Turkana boy (H. ergaster) in 1984 evidenced that, despite its Homo sapiens-like anatomy, ergaster may not have been capable of producing sounds comparable to modern human speech. It likely communicated in a proto-language lacking the fully developed structure of modern human language but more developed than the non-verbal communication used by chimpanzees.[76] This inference is challenged by the find in Dmanisi, Georgia, of an H. ergaster / erectus vertebrae (at least 150,000 years earlier than the Turkana Boy) that reflects vocal capabilities within the range of H. sapiens.[39] Both brain size and the presence of the Broca's area also support the use of articulate language.[77]

Linguist Daniel Everett has argued that H. erectus may have been the first hominin to evolve the capability of language because their level of social organization and technical sophistication must have required a complex communication system.[78]

H. erectus was probably the first hominin to live in small, familiar band-societies similar to modern hunter-gatherer band-societies,[79] and is thought to be the first hominin species to hunt in coordinated groups, to use complex tools, and to care for infirm or weak companions.

Descendants and subspecies

Homo erectus is the most, or one of the most, long-lived species of Homo, having existed well over one million years and perhaps over two million years; by contrast, Homo sapiens emerged about a quarter million years ago. If considering Homo erectus in its strict sense (that is, as referring to only the Asian variety) no consensus has been reached as to whether it is ancestral to H. sapiens or any later human species.

Homo erectus

- Homo erectus bilzingslebenensis (0.37 Ma)

- Homo erectus erectus (Java Man, 1.6–0.5 Ma)

- Homo erectus georgicus (1.8–1.6 Ma)

- Homo erectus heidelbergensis (0.7–0.3 Ma), now mostly treated as a derived species, H. heidelbergensis.[80]

- Homo erectus lantianensis (Lantian Man, 1.6 Ma)

- Homo erectus nankinensis (Nanjing Man, 0.6 Ma)

- Homo erectus palaeojavanicus (Meganthropus, 1.4–0.9 Ma)

- Homo erectus pekinensis (Peking Man, 0.7 Ma)

- Homo erectus soloensis (Solo Man, 0.55—0.14 Ma)[81]

- Homo erectus tautavelensis (Tautavel Man, 0.45 Ma)

- Homo erectus yuanmouensis (Yuanmou Man)

"Wushan Man" was proposed as Homo erectus wushanensis, but is now thought to be based upon fossilized fragments of an extinct non-hominin ape.[82]

Related species

On many archaic humans there is no definite consensus as to whether they should be classified as subspecies of either H. erectus or H. sapiens, or as separate species

- African H. erectus candidates

- Homo ergaster ("African H. erectus)

- Homo naledi (or H. e. naledi)

- Eurasian H. erectus candidates:

- Homo antecessor (or H. e. antecessor)

- Homo heidelbergensis (or H. e. heidelbergensis)

- Homo cepranensis (or H. e. cepranensis)

- Homo floresiensis [83]

- Homo sapiens candidates

- Homo neanderthalensis (or H. s. neanderthalensis)

- Homo denisova (or H. s. denisova or Homo sp. Altai, and Homo sapiens subsp. Denisova)

- Homo rhodesiensis (or H. s. rhodensis)

- Homo heidelbergensis (or H. s. heidelbergensis)

- Homo sapiens idaltu

- the Narmada fossil, discovered in 1982 in Madhya Pradesh, India, was at first suggested as H. erectus (Homo erectus narmadensis) but later recognized as H. sapiens.[84]

Individual fossils

Some of the major Homo erectus fossils:

- Indonesia (island of Java): Trinil 2 (holotype), Sangiran collection, Sambungmachan collection,[85] Ngandong collection

- China ("Peking Man"): Lantian (Gongwangling and Chenjiawo), Yunxian, Zhoukoudian, Nanjing, Hexian

- Kenya: KNM ER 3883, KNM ER 3733

- Vértesszőlős, Hungary "Samu"

- Vietnam: Northern, Tham Khuyen,[86] Hoa Binh

- Republic of Georgia: Dmanisi collection ("Homo erectus georgicus")

- Ethiopia: Daka calvaria

- Eritrea: Buia cranium (possibly H. ergaster)[87]

- Denizli Province, Turkey: Kocabas fossil[88]

Gallery

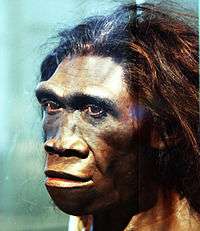

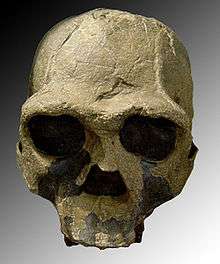

Homo erectus tautavelensis skull.

Homo erectus tautavelensis skull..jpg)

A reconstruction based on evidence from the Daka Member, Ethiopia

A reconstruction based on evidence from the Daka Member, Ethiopia Original fossils of Pithecanthropus erectus (now Homo erectus) found in Java in 1891.

Original fossils of Pithecanthropus erectus (now Homo erectus) found in Java in 1891.

See also

General:

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

References

- 1 2 Homo erectus soloensis, found in Java, is considered the latest known survival of H. erectus. Formerly dated to as late as 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, a 2011 study pushed back the date of its extinction of H. e. soloensis to 143,000 years ago at the latest, more likely before 550,000 years ago. Indriati E, Swisher CC III, Lepre C, Quinn RL, Suriyanto RA, et al. 2011 The Age of the 20 Meter Solo River Terrace, Java, Indonesia and the Survival of Homo erectus in Asia.PLoS ONE 6(6): e21562. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021562.

- ↑ based on numerous fossil remains of H. erectus. Museum of Prehistory Tautavel, France (2008 photograph)

- ↑ Reconstruction by John Gurche (2010), Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, based on KNM ER 3733 and 992. Abigail Tucker, "A Closer Look at Evolutionary Faces", Smithsonian.com, 25 February 2010.

- ↑ Reconstruction by W. Schnaubelt & N. Kieser (Atelier WILD LIFE ART), 2006, Westfälisches Museum für Archäologie, Herne, Germany.

- ↑ Haviland, William A.; Walrath, Dana; Prins, Harald E. L.; McBride, Bunny (2007). Evolution and Prehistory: The Human Challenge (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-495-38190-7.

- ↑ Klein, R. (1999). The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226439631.

- ↑ Antón, S. C. (2003). "Natural history of Homo erectus". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 122: 126–170. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10399.

By the 1980s, the growing numbers of H. erectus specimens, particularly in Africa, led to the realization that Asian H. erectus (H. erectus sensu stricto), once thought so primitive, was in fact more derived than its African counterparts. These morphological differences were interpreted by some as evidence that more than one species might be included in H. erectus sensu lato (e.g., Stringer, 1984; Andrews, 1984; Tattersall, 1986; Wood, 1984, 1991a, b; Schwartz and Tattersall, 2000) ... Unlike the European lineage, in my opinion, the taxonomic issues surrounding Asian vs. African H. erectus are more intractable. The issue was most pointedly addressed with the naming of H. ergaster on the basis of the type mandible KNM-ER 992, but also including the partial skeleton and isolated teeth of KNM-ER 803 among other Koobi Fora remains (Groves and Mazak, 1975). Recently, this specific name was applied to most early African and Georgian H. erectus in recognition of the less-derived nature of these remains vis à vis conditions in Asian H. erectus (see Wood, 1991a, p. 268; Gabunia et al., 2000a). At least portions of the paratype of H. ergaster (e.g., KNM-ER 1805) are not included in most current conceptions of that taxon. The H. ergaster question remains famously unresolved (e.g., Stringer, 1984; Tattersall, 1986; Wood, 1991a, 1994; Rightmire, 1998b; Gabunia et al., 2000a; Schwartz and Tattersall, 2000), in no small part because the original diagnosis provided no comparison with the Asian fossil record

- ↑ Suwa G, Asfaw B, Haile-Selassie Y, White T, Katoh S, WoldeGabriel G, Hart W, Nakaya H, Beyene Y (2007). "Early Pleistocene Homo erectus fossils from Konso, southern Ethiopia". Anthropological Science. 115 (2): 133–151. doi:10.1537/ase.061203.

- 1 2 Kaifu, Y., et al. (2005). "Taxonomic affinities and evolutionary history of the Early Pleistocene hominids of Java: dentognathic evidence". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 128: 709-726.

- ↑ Skull suggests three early human species were one : Nature News & Comment

- 1 2 David Lordkipanidze, Marcia S. Ponce de Leòn, Ann Margvelashvili, Yoel Rak, G. Philip Rightmire, Abesalom Vekua, Christoph P. E. Zollikofer (18 October 2013). "A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo". Science. 342 (6156): 326–331. doi:10.1126/science.1238484.

- ↑ Switek, Brian (17 October 2013). "Beautiful Skull Spurs Debate on Human History". National Geographic. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ Swisher, Curtis & Lewin 2000, p. 70.

- ↑ "The First Knock at the Door". Peking Man Site Museum.

In the summer of 1921, Dr. J.G. Andersson and his companions discovered this richly fossiliferous deposit through the local quarry men's guide. During examination he was surprised to notice some fragments of white quartz in tabus, a mineral normally foreign in that locality. The significance of this occurrence immediately suggested itself to him and turning to his companions, he exclaimed dramatically "Here is primitive man, now all we have to do is find him!"

- ↑ "The First Knock at the Door". Peking Man Site Museum.

For some weeks in this summer and a longer period in 1923 Dr. Otto Zdansky carried on excavations of this cave site. He accumulated an extensive collection of fossil material, including two Homo erectus teeth that were recognized in 1926. So, the cave home of Peking Man was opened to the world.

- ↑ from sino-, a combining form of the Greek Σίνα "China", and the Latinate pekinensis, "of Peking"

- ↑ "Review of the History". Peking Man Site Museum.

During 1927-1937, abundant human and animal fossils as well as artefact were found at Peking Man Site, it made the site to be the most productive one of the Homo erectus sites of the same age all over the world. Other localities in the vicinity were also excavated almost at the same time.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles R. (1871). The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray. ISBN 0-8014-2085-7.

- ↑ "Oldest known member of human family found in Ethiopia". New Scientist. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-07.

- ↑ F. Spoor; M. G. Leakey; P. N. Gathogo; F. H. Brown; S. C. Antón; I. McDougall; C. Kiarie; F. K. Manthi; L. N. Leakey (9 August 2007). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323. "A partial maxilla assigned to H. habilis reliably demonstrates that this species survived until later than previously recognized, making an anagenetic relationship with H. erectus unlikely. [...] these two early taxa were living broadly sympatrically in the same lake basin for almost half a million years."

- ↑ Ferring, R.; Oms, O.; Agusti, J.; Berna, F.; Nioradze, M.; Shelia, T.; Tappen, M.; Vekua, A.; Zhvania, D.; Lordkipanidze, D. (2011). "Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (26): 10432. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108. PMC 3127884. PMID 21646521.

- ↑ Augusti, Jordi; Lordkipanidze, David (June 2011). "How "African" was the early human dispersal out of Africa?". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (11–12): 1338–1342. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.012.

- ↑ ROBINSON JT (January 1953). "The nature of Telanthropus capensis". Nature. 171 (4340): 33. doi:10.1038/171033a0. PMID 13025468.

- ↑ Frederick E. Grine; John G. Fleagle; Richard E. Leakey (1 Jun 2009). "Chapter 2: Homo habilis—A Premature Discovery: Remember by One of Its Founding Fathers, 42 Years Later". The First Humans: Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo. Springer. p. 7.

- ↑ F. Spoor; M. G. Leakey; P. N. Gathogo; F. H. Brown; S. C. Antón; I. McDougall; C. Kiarie; F. K. Manthi; L. N. Leakey (2007-08-09). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323. "A partial maxilla assigned to H. habilis reliably demonstrates that this species survived until later than previously recognized, making an anagenetic relationship with H. erectus unlikely"

- 1 2 Kalb, Jon E (2001). Adventures in the Bone Trade: The Race to Discover Human Ancestors in Ethiopia's Afar Depression. Springer. p. 76. ISBN 0-387-98742-8. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ↑ Cornevin, Robert (1967). Histoire de l'Afrique. Payotte. p. 440. ISBN 2-228-11470-7.

- ↑ "Mikko's Phylogeny Archive". Finnish Museum of Natural History, University of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Wood, Bernard (11 July 2002). "Palaeoanthropology: Hominid revelations from Chad" (PDF). Nature. 418 (6894): 133–135. doi:10.1038/418133a. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ (Servant 1983, pp. 462-464).

- ↑ Vekua A, Lordkipanidze D, Rightmire GP, Agusti J, Ferring R, Maisuradze G, Mouskhelishvili A, Nioradze M, De Leon MP, Tappen M, Tvalchrelidze M, Zollikofer C (2002). "A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia". Science. 297 (5578): 85–9. doi:10.1126/science.1072953. PMID 12098694.

- 1 2 Lordkipanidze D, Jashashvili T, Vekua A, Ponce de León MS, Zollikofer CP, Rightmire GP, Pontzer H, Ferring R, Oms O, Tappen M, Bukhsianidze M, Agusti J, Kahlke R, Kiladze G, Martinez-Navarro B, Mouskhelishvili A, Nioradze M, Rook L (2007). "Postcranial evidence from early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia" (PDF). Nature. 449 (7160): 305–310. doi:10.1038/nature06134. PMID 17882214.

- ↑ Lordkipanidze, D.; Vekua, A.; Ferring, R.; Rightmire, G. P.; Agusti, J.; Kiladze, G.; Mouskhelishvili, A.; Nioradze, M.; Ponce De León, M. S. P.; Tappen, M.; Zollikofer, C. P. E. (2005). "Anthropology: The earliest toothless hominin skull". Nature. 434 (7034): 717–718. doi:10.1038/434717b. PMID 15815618.

- ↑ Ferring, R.; Oms, O.; Agusti, J.; Berna, F.; Nioradze, M.; Shelia, T.; Tappen, M.; Vekua, A.; Zhvania, D.; Lordkipanidze, D. (2011). "Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (26): 10432–10436. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108. PMC 3127884. PMID 21646521.

- ↑ Gibbons, A. (2003). "A Shrunken Head for African Homo erectus" (PDF). Science. 300 (5621): 893a. doi:10.1126/science.300.5621.893a. PMID 12738831.

- ↑ Tattersall, I.; Schwartz, J. H. (2009). "Evolution of the GenusHomo". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 37: 67–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100202.

- ↑ Rightmire, G. P.; Lordkipanidze, D.; Vekua, A. (2006). "Anatomical descriptions, comparative studies and evolutionary significance of the hominin skulls from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia". Journal of Human Evolution. 50 (2): 115–141. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.07.009. PMID 16271745.

- ↑ Gabunia, L.; Vekua, A.; Lordkipanidze, D.; Swisher Cc, 3.; Ferring, R.; Justus, A.; Nioradze, M.; Tvalchrelidze, M.; Antón, S. C.; Bosinski, G.; Jöris, O.; Lumley, M. A.; Majsuradze, G.; Mouskhelishvili, A. (2000). "Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, geological setting, and age". Science. 288 (5468): 1019–1025. doi:10.1126/science.288.5468.1019. PMID 10807567.

- 1 2 Bower, Bruce (3 May 2006). "Evolutionary back story: Thoroughly modern spine supported human ancestor". Science News. 169 (18): 275–276. doi:10.2307/4019325. JSTOR 4019325.

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble (19 September 2007). "New Fossils Offer Glimpse of Human Ancestors". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ↑ Rightmire, G. Philip; Van Arsdale, Adam P.; Lordkipanidze, David (2008). "Variation in the mandibles from Dmanisi, Georgia". Journal of Human Evolution. 54 (6): 904–8. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.02.003. PMID 18394678.

- ↑ Ian Sample (17 October 2013). "Skull of Homo erectus throws story of human evolution into disarray". The Guardian.

- ↑ Zhu Zhaoyu (朱照宇); Dennell, Robin; Huang Weiwen (黄慰文); Wu Yi (吴翼); Qiu Shifan (邱世藩); Yang Shixia (杨石霞); Rao Zhiguo (饶志国); Hou Yamei (侯亚梅); Xie Jiubing (谢久兵); Han Jiangwei (韩江伟); Ouyang Tingping (欧阳婷萍) (2018). "Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0299-4. ISSN 0028-0836. Barras, Colin (2018). "Tools from China are oldest hint of human lineage outside Africa". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-05696-8. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ↑ Krantz, G. S. (1975). "An explanation for the diastema of Javan erectus Skull IV". In: Paleoanthropology, Morphology and Paleoecology. La Hague: Mouton, 361-372.

- ↑ Paul Rincon (11 March 2009). "'Peking Man' older than thought". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Shen, G; Gao, X; Gao, B; Granger, De (March 2009). "Age of Zhoukoudian Homo erectus determined with (26)Al/(10)Be burial dating". Nature. 458 (7235): 198–200. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..198S. doi:10.1038/nature07741. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19279636. "'Peking Man' older than thought". BBC News. 11 March 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Qian F, Li Q, Wu P, Yuan S, Xing R, Chen H, and Zhang H (1991). Lower Pleistocene, Yuanmou Formation: Quaternary Geology and Paleoanthropology of Yuanmou, Yunnan, China. Beijing: Science Press, pp. 17-50

- ↑ W. Rukang, L. Xingxue, "Homo erectus from Nanjing", PaleoAnthropology, 2003. 6 September 2017. J. Zhao, K. Hu, K. D. Collerson, H. Xu, "Thermal ionisation mass spectrometry U-series dating of a hominid site near Nanjing, China" Archived 8 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Geology, 2001. 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Finding showing human ancestor older than previously thought offers new insights into evolution, 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Jones, Tim. "Lithic Assemblage Dated to 1.57 Million Years Found at Lézignan-la-Cébe, Southern France «". Anthropology.net. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ↑ Moore, Matthew (8 July 2010). "Norfolk earliest known settlement in northern Europe". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Ghosh, Pallab (7 July 2010). "Humans' early arrival in Britain". BBC. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Weidenreich, F. (1943). "The "Neanderthal Man" and the ancestors of "Homo Sapiens"". American Anthropologist. 45: 39–48. doi:10.1525/aa.1943.45.1.02a00040. JSTOR 662864.

- ↑ Jelinek, J. (1978). "Homo erectus or Homo sapiens?". Rec. Adv. Primatol. 3: 419–429.

- ↑ Wolpoff, M.H. (1984). "Evolution of Homo erectus: The question of stasis". Palaeobiology. 10 (4): 389–406. JSTOR 2400612.

- ↑ Frayer, D.W., Wolpoff, M.H.; Thorne, A.G.; Smith, F.H.; Pope, G.G. (1993). "Theories of modern human origins: The paleontological test". American Anthropologist. 95: 14–50. doi:10.1525/aa.1993.95.1.02a00020. JSTOR 681178.

- ↑ Tattersall, Ian and Jeffrey Schwartz (2001). Extinct Humans. Boulder, Colorado: Westview/Perseus. ISBN 0-8133-3482-9.

- 1 2 Swisher, Carl Celso III; Curtis, Garniss H. and Lewin, Roger (2002) Java Man, Abacus, ISBN 0-349-11473-0.

- ↑ "A footprint in the sands of time". The Economist. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ↑ Bryson, Bill (2005). A Short History of Nearly Everything: Special Illustrated Edition. Toronto: Doubleday Canada. ISBN 0-385-66198-3.

- ↑ Khanna, Dev Raj (2004). Human Evolution. Discovery Publishing House. p. 195. ISBN 978-8171417759. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

African H. erectus, with a mean stature of 170 cm, would be in the tallest 17 percent of modern populations, even if we make comparisons only with males

- ↑ Roylance, Frank D. Roylance (6 February 1994). "A Kid Tall For His Age". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

Clearly this population of early people were tall, and fit. Their long bones were very strong. We believe their activity level was much higher than we can imagine today. We can hardly find Olympic athletes with the stature of these people

- 1 2 Stringer, C. (2012). "What makes a modern human". Nature. 485 (7396): 33–35. doi:10.1038/485033a. PMID 22552077.

- 1 2 "Figure 5. Temporal and Geographical Distribution of Hominid Populations Redrawn from Stringer (2003)" (edited from source), in Reed, David L.; Smith, Vincent S.; Hammond, Shaless L.; et al. (November 2004). "Genetic Analysis of Lice Supports Direct Contact between Modern and Archaic Humans". PLOS Biology. San Francisco, CA: PLOS. 2 (11): e340. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020340. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 521174. PMID 15502871.

- ↑ Whitfield, John (18 February 2008). "Lovers not fighters". Scientific American.

- ↑ Toth, Nicholas; Schick, Kathy (2007). Toth, Nicholas; Schick, Kathy (2007). "Handbook of Paleoanthropology". Handbook of Paleoanthropology: 1943–1963. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_64. ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4. In Henke, H.C. Winfried; Hardt, Thorolf; Tatersall, Ian. Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Volume 3. Berlin; Heidelberg; New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 1944. (PRINT: ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4 ONLINE: ISBN 978-3-540-33761-4)

- ↑ "The Pleistocene Epoch". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ↑ Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ↑ The Earth Institute. (2011-09-01). Humans Shaped Stone Axes 1.8 Million Years Ago, Study Says. Columbia University. Accessed 5 January 2012.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann (13 March 1998). "Paleoanthropology: Ancient Island Tools Suggest Homo erectus Was a Seafarer". Science. 279 (5357): 1635–1637. doi:10.1126/science.279.5357.1635.

- ↑ Oldest stone tool ever found in Turkey discovered by the University of Royal Holloway London and published in ScienceDaily on December 23, 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 James, Steven R. (February 1989). "Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence" (PDF). Current Anthropology. University of Chicago Press. 30 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1086/203705. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (29 April 2004). "Early human fire skills revealed". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- 1 2 Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together, Worlds Apart. New York: Norton. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-393-92207-3.

- ↑ Pringle, Heather (2 April 2012), "Quest for Fire Began Earlier Than Thought", ScienceNOW, American Association for the Advancement of Science, archived from the original on 15 April 2013, retrieved 2012-04-04

- ↑ Ruhlen, Merritt (1994). The origin of language: tracing the evolution of the mother tongue. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-58426-6.

- ↑ Leakey, Richard (1992). Origins Reconsidered. Anchor. pp. 257–58. ISBN 0-385-41264-9.

- ↑ Everett, D. L. (2017). How Language Began: The Story of Humanity's Greatest Invention. Liveright Publishing.

- ↑ Boehm, Christopher (1999). Hierarchy in the forest: the evolution of egalitarian behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 198. ISBN 0-674-39031-8.

- ↑ The paleontology institute at Heidelberg University, where the type specimen is kept since 1908, as late as 2010 still classified it as Homo erectus heidelbergensis. This was reportedly changed to Homo heidelbergensis, accepting the categorization as separate species, in 2015. "Homo heidelbergensis". Sammlung des Instituts für Geowissenschaften. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ long assumed to have lived on Java at least as late as about 50,000 years ago but re-dated in 2011 to a much older age.Finding showing human ancestor older than previously thought offers new insights into evolution, 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Ciochon RL. (2009). "The mystery ape of Pleistocene Asia. Nature. 459: 910-911. doi:10.1038/459910a.

- ↑ There was long-standing uncertainty whether H. floresiensis should be considered close to H. erectus, close to H. sapiens, or an altogether separate species. In 2017, it was suggested on morphological grounds that H. floresiensis is a sister species to either H. habilis or to a minimally habilis-erectus-ergaster-sapiens clade, and its line much more ancient than Homo erectus itself. Argue, Debbie; Groves, Colin P. (21 April 2017). "The affinities of Homo floresiensis based on phylogenetic analyses of cranial, dental, and postcranial characters". Journal of Human Evolution. 107: 107–133. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.02.006. PMID 28438318.

- ↑ Kenneth A. R. Kennedy Arun Sonakia John Chiment K. K. Verma, "Is the Narmada hominid an Indian Homo erectus?", American Journal of Physical Anthropology 86.4 (December 1991), 475-496, doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330860404.

- ↑ Delson E, Harvati K, Reddy D, et al. (April 2001). "The Sambungmacan 3 Homo erectus calvaria: a comparative morphometric and morphological analysis". The Anatomical Record. 262 (4): 380–97. doi:10.1002/ar.1048. PMID 11275970.

- ↑ Ciochon R, Long VT, Larick R, et al. (April 1996). "Dated co-occurrence of Homo erectus and Gigantopithecus from Tham Khuyen Cave, Vietnam". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (7): 3016–20. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.7.3016. PMC 39753. PMID 8610161.

- ↑ Schuster, Angela M. H. (September–October 1998). "New Skull from Eritrea". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America; republished online at archive.org. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ↑ Kappelman J, Alçiçek MC, Kazanci N, Schultz M, Ozkul M, Sen S (January 2008). "First Homo erectus from Turkey and implications for migrations into temperate Eurasia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 135 (1): 110–16. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20739. PMID 18067194.

Further reading

- Leakey, Richard; Walker, Alan (November 1985). "Homo Erectus Unearthed". National Geographic. Vol. 168 no. 5. pp. 624–629. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo erectus. |

- Homo erectus Origins - Exploring the Fossil Record - Bradshaw Foundation

- Archaeology Info

- Homo erectus – The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- Possible co-existence with Homo Habilis – BBC News

- John Hawks's discussion of the Kocabas fossil

- Peter Brown's Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology

- The Age of Homo erectus – Interactive Map of the Journey of Homo erectus out of Africa

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).