Jar burial

Jar burials are human burials where the corpse is placed into a large earthenware and then is interred. Jar-burials are a repeated pattern at a site or within an archaeological culture. When an anomalous burial is found in which a corpse or cremated remains have been interred, it is not considered a "jar burial".

Jar burial can be traced to various regions across the globe. It is noted to have been practiced as early as BCE 900,[1] and as recent as CE 15-17th centuries [2] Particular areas of studies on jar burial excavations include India, Indonesia, Lebanon, Palestine,Taiwan, Japan, Cambodia, Iran, Syria, Sumatra, Egypt, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Vanuatu, and Vietnam. These differing locations call for different methods, accoutrements, and rational behind the jar burial practices. Cultural practices ranged from primary [3][4] versus secondary burial,[1][2][5] burial offerings (bronze/iron tools, weapons and bronze/silver/gold ornaments, wood, stone, clay, glass, and paste) in/around burials,[2][6] and hierarchical structures represented in the location/method of the placement of jars.[6]

Among many cultures, a period of waiting occurs between the first burial and a second burial that often coincides with the duration of decomposition. The origin of this practice is considered to be the different concept of death held by these cultures. In such societies, death is held to involve a slow change, a passage from the visible society of the living to the invisible one of the dead. During the period of decomposition, the corpse is sometimes treated as if it were alive, provided with food and drink and surrounded by company. Some groups on the island of Borneo, for example, attach mystical importance to the disintegration of the body, sometimes collecting and carefully disposing of the liquids produced by decomposition.

Methods

As previously stated, jar burial culture was employed by peoples who chose this practice for primary or secondary burial. Primary burial refers to the acts performed on the body immediately after death. In some cases of Jar Burial, primary burial with this technique was a lot more difficult to carry out. In Cretan societies, the dead body would be bound tightly to fit into the desired jar. This was believed to be originally intended for infants and small children, but it evolved into larger categories of adults.[3] Adults, however required much larger jars, deeper graves, and more man-power to In Egyptian societies, the body also could be sat upright, and then the jar would be forced on top of the body. Egyptians also would place the body into the jar themselves, rather than pushing the jar downwards, but this would create a need for a lid. Lids are not specific pieces of pottery, they have been found to be as simple as a rock or another jar.[5] The preference of how it the body was placed did not have any certain significance.[4]

Secondary burials are different acts performed on body that has already been buried. The allotted time between primary and secondary burials varies between cultures, however an emphasis is placed on waiting until the body has decomposed, and whatever technique is carried out as "secondary", is dealing with only defleshed bones.[2] With jar burials, the defleshed bones were cleaned and subsequently put in a jar.[5]

Jar Additions

Types of jars and additional components vary from location to culture. Different shapes of jars can indicate the prestige or societal level of the deceased, or it can be a commonplace jar. Funerary offerings are sometimes placed in or around the jars, thus revealing more information about the value different peoples have for certain items.

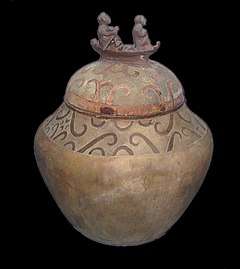

Decoration

Pithoi were typical storage jars, and were commonly used for burials, and they employ vertical round to oval handles (29).[7] Carvings on jars have also been found, sometimes depicting local divine beings of the time. This is thought to assist in the passing of that individual to a realm beyond life. The carvings on jars are not standardized, meaning there is no particular pattern of a certain carving on multiple jars, but most carvings have been observed in Egypt[1]

Some jars are specifically manufactured for jar burials, due to the varying size of bodies and grave sites available to different cultures.[5]

Accoutrements

Many jar burial sites have also been accompanied by more than just the skeletons and jars. Beads, swords, mirrors, and other animal bones have been found in and around jars. In the Cardamom Mountains, a large amount of beads have been found in jars.[6] These are most likely offerings to the deceased, in the same way that tombs have gifts in them. However the presence of these beads and other offerings give great insight into the lifestyle of the people. By studying the materials and methods the beads were made of, researchers have been able to link various cultures together based on their likely trade operations—the way they obtained exotically different beads than what was typical to their own culture.[2]

Gallery

Geographical Locations of Jar Burials

| Location | Dates | Cultural Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | AD 1395 - 1650 [8] | In the Cardamom Mountains specifically, a mass burial site with over 152 individuals was discovered. Using radiocarbon dating, researchers were able to indicate that this specific site was only an active burial site for about 15 years. In addition to human remains, they were able to genetically identify animal bones also (pigs, dogs,). These findings were deduced to have been placed with the grave as offerings. When analyzing the jars themselves, they were identified as being jars obtained through maritime trading or local ceramic production.[2][9] |

| Egypt | -- | In Egypt, prior to utilizing an embalming process, there is evidence that they practiced jar-burial. They used hemispherical and bowl urns, and the shape was not indicative of any external meaning. Some jars found here had inscriptions on the outside resembling common deities worshipped by the Egyptian people.[4] |

| Indonesia | -- | Jar burials are known from Java, Sumatra, Bali, Sulawesi, Salayar Island, and Sumba. Most sites are found in eastern Indonesia, with the burials restricted to coastal areas.[10] |

| Iran | -- | In Iran, we do not find any items accompanying the burials, and no indication of offerings. However, this area is dictated by tropical conditions, and these conditions resulted in frequent and repeated flooding resulting in sites and artifacts that were not well preserved[11][12] |

| Japan | BC 300 - AD 300 | Jar Burial was practiced in Japan for about 600 years. Sites here show the most intricate planning of burial sites, and the planning reflected a social hierarchy within the site. Certain areas of the site had multiple burials clumped together, with the most recent death buried closer to the surface, and the oldest would lie deeper and underneath the recent deaths. These clumps all faced each other, so when the site was opened again to bury someone new, all of the clumps were 'connected' and more inviting to the person about to be buried. Within clumps, most have offerings in or around the graves. Offerings plus the intricate planning of the site indicates that a lot of care was put into the disposal of the dead in this culture.[13][6] |

| Lebanon | -- | In the sites discovered, Lebanese jar burials were particularly reserved for infants. It was rare to find an adult who had been buried in a jar.[14] |

| Malaysia | -- | Burial jars have been found in the Niah Caves of Sarawak.[10] |

| Palestine | -- | Palestinian jar burials were done as "Subfloor burial", in which they were buried under floors in rooms of the house. The areas chosen were mostly high traffic areas where household tasks were performed, thus connecting them with the main parts of everyday life. In these burials there were occasional materials found with the bodies such as shells, but there has been no evidence that these were placed with the bodies as offerings.[1] |

| Philippines | -- | The practice of jar burial was widespread in the Late Neolithic period of the Philippines, with archeological examples from northern Luzon, Marinduque, Masbate, Sorsogon, Palawan, and in Sarangani in Mindanao. They were usually placed in caves and are made from clay or carved stone. The oldest example is the Manunggul Jar from the Tabon Cave, dated to 890–710 BCE.[15][16][10] |

| Sumatra | -- | Secondary burial was carried out using the jar burial method. The only other additions of note were shards of pottery found in some urns with the bodies.[17] |

| Syria | BC 1800-BC 1750 | Syrian jar burial was noted to have been practiced for a short period of time. The vessels used to bury individuals in did not always happen to be jars; they ranged from pots to goblets, and had pins and cylinder seals inside.[18] |

| Taiwan | -- | Typical to Austronesian Taiwanese jar burial, glass beads were laid to rest within the jars along with the body. Jar burial was used as a means of secondary burial here.[5] |

| Thailand | -- | Upon extensive testing, studies have shown that individuals buried in jars had different diets than other inhabitants of Thailand. This suggests a different social status of those buried in jars, or that those individuals were immigrants and brought that practice with them to Thailand.[19] |

| Vanuatu | -- | In Vanuatu, almost all jar burials were found with ceramic fragments in the jars. It is unclear whether those are shards of other broken jars or if they were placed in the jars as offerings.[20] |

| Vietnam | -- | Burial jars in Vietnam are mostly from Austronesian sites in southern and central Vietnam. The most notable are burial jars from the Sa Huỳnh culture.[16] |

See also

References

- Ivashchenko, M. “Kuvshinnye pogrebeniia Azerbaidzhana i Gruzii.” Izvestiia AN Azerbaidzhanskoi SSR, 1947, no. 1.

- Kaziev, S. M. AVbom kuvshinnykh pogrebenii. Baku, 1960.

- Golubkina, T. I. “Kul’tura kuvshinnykh pogrebenii v Azerbaidzhane.” In the collection Tr. Muzeia istorii Azerbaidzhana, vol. 4. Baku, 1961.

- A. Nnoeshvili, Funeral Practice of Transcaucasian Nations (The 8th B.C.-the 8th A.D. Jar Burials), Tbilisi, 1992, ISBN 5-520-01028-5

- 1 2 3 4 Birney, Kathleen; Doak, Brian R. (2011). "Funerary Iconography on an Infant Burial Jar from Ashkelon". Israel Exploration Journal. 61 (1): 32–53. JSTOR 23214220.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carter, A. K.; Dussubieux, L.; Beavan, N. (2016-06-01). "Glass Beads from 15th-17th CenturyCEJar Burial Sites in Cambodia's Cardamom Mountains". Archaeometry. 58 (3): 401–412. doi:10.1111/arcm.12183. ISSN 1475-4754.

- 1 2 Maria., Mina, (2016). An Archaeology of Prehistoric Bodies and Embodied Identities in the Eastern Mediterranean. Triantaphyllou, Sevi., Papadatos, Giannēs, 1972-. Havertown: Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785702914. OCLC 960760548.

- 1 2 3 Wood, W. H. (1910). "Jar-Burial Customs and the Question of Infant Sacrifice in Palestine". The Biblical World. 36 (3): 166–175. JSTOR 3141677.

- 1 2 3 4 5 DE BEAUCLAIR, INEZ (1972). "Jar Burial on Botel Tobago Island". Asian Perspectives. 15 (2): 167–176. JSTOR 42927787.

- 1 2 3 4 Mizoguchi, Koji (June 2005). "Genealogy in the ground: observations of jar burials of the Yayoi period, northern Kyushu, Japan". Antiquity. 79 (304): 316–326. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00114115. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ↑ Mochlos IIC : period IV, the Mycenaean settlement and cemetery : the human remains and other finds. Soles, Jeffrey S., 1942-, Davaras, Kōstēs. Philadelphia, Pa.: INSTAP Academic Press. 2011. ISBN 9781931534604. OCLC 852160173.

- ↑ Beavan, Nancy; Halcrow, Sian; McFadgen, Bruce; Hamilton, Derek; Buckley, Brendan; Sokha, Tep; Shewan, Louise; Sokha, Ouk; Fallon, Stewart (2012/ed). "Radiocarbon Dates from Jar and Coffin Burials of the Cardamom Mountains Reveal a Unique Mortuary Ritual in Cambodia's Late- to Post-Angkor Period (15th–17th Centuries AD)". Radiocarbon. 54 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.v54i1.15828. ISSN 0033-8222. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Beavan, Nancy; Hamilton, Derek; Sokha, Tep; Sayle, Kerry (2015/ed). "Radiocarbon Dates from the Highland Jar and Coffin Burial Site of Phnom Khnang Peung, Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia". Radiocarbon. 57 (1): 15–31. doi:10.2458/azu_rc.57.18194. ISSN 0033-8222. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 Lam, Thi My Dzung. "Jar burial tradition in Southeast Asia". Museum Anthropology. Hanoi National University. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ FARJAMIRAD, M. (2016). FUNERARY OBJECTS FROM A SASANIAN BURIAL JAR ON THE BUSHEHR PENINSULA. Iranica Antiqua, 51301-311. doi:10.2143/IA.51.0.3117837

- ↑ Elizabeth), Murray, Sarah (Sarah (2011). Making an exit : from the magnificent to the macabre -- how we dignify the dead (1st ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312533021. OCLC 707969689.

- ↑ Mizoguchi, Koji (September 2014). "The centre of their life-world: the archaeology of experience at the Middle Yayoi cemetery of Tateiwa-Hotta, Japan". Antiquity. 88 (341): 836–850. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00050729. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ↑ Alan Ogden & Holger Schutkowski (2013) Human Remains from Middle Bronze Age Burials at Sidon, Lebanon: the 2001 Season, Levant, 36:1, 159-166, DOI: 10.1179/lev.2004.36.1.159

- ↑ Jacinto, Al. "2,000-year-old artifacts, cave found in Mindanao". GMA News Online. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- 1 2 Nguyen, Thi Hau (December 2011). "SEAsia Prehistory told in jar burial". Vietnam Heritage Magazine. 1 (10).

- ↑ Soeroso (1997). "Recent discoveries of jar burial sites in South Sumatra". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 84: 418–422. JSTOR 43731472.

- ↑ JAMIESON, Andrew S. "Ceramic Vessels from the Middle Bronze Age Jar Burial F167 at Tell Ahmar". Ancient Near Eastern Studies. 35 (0): 106–119. doi:10.2143/anes.35.0.525773.

- ↑ King, Charlotte L.; Bentley, R. Alexander; Tayles, Nancy; Viðarsdóttir, Una Strand; Nowell, Geoff; Macpherson, Colin G. "Moving peoples, changing diets: isotopic differences highlight migration and subsistence changes in the Upper Mun River Valley, Thailand". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (4): 1681–1688. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.11.013.

- ↑ "Description of jar burial practice at the Teouma Lapita cemetery (Efate, Vanuatu) and preliminary comparisons with Southeast Asia jar burial traditions". HOMO - Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 64 (2): 159–160. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2013.02.043.

.jpg)