Paranthropus robustus

| Paranthropus robustus | |

|---|---|

| |

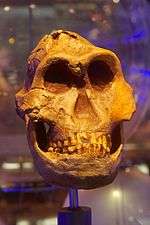

| Original Skull of Paranthropus robustus SK 48 at the Transvaal Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | †Paranthropus |

| Species: | †P. robustus |

| Binomial name | |

| Paranthropus robustus Broom, 1938 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Australopithecus robustus (Dart, 1938) | |

Paranthropus robustus (or Australopithecus robustus) is an early hominin, originally discovered in Southern Africa in 1938. Particularly regarding cranial features, the development of P. robustus seemed to be in the direction of a "heavy-chewing complex". On account of the definitive traits associated with this "robust" line of australopithecine, anthropologist Robert Broom established the genus Paranthropus and placed this species in it.

Paranthropus robustus is generally dated to have lived between 2.0 and 1.2 million years ago. It had large jaws and jaw muscles with the accompanying sagittal crest, and post-canine teeth that were adapted to serve in the dry environment they lived in.

Discovery

After Raymond Dart’s discovery of Australopithecus africanus, Robert Broom was in favour of Dart's claim that Australopithecus africanus was an ancestor of Homo sapiens. However, there was a great deal of skepticism and criticism from the academic community. Many claimed that Dart had been premature in naming the species as the type specimen, called Taung Child, was a represented by a single skull of a juvenile. It was thought that such important claims should be based on a full skeleton of an adult.

Broom was a Scottish doctor then working in South Africa, who began making his own excavations in Southern Africa to find more specimens of A. africanus, to help strengthen Dart's position. It was his intent to find complete adult skeletons that would justify the species designation of A. africanus, and further justify its place as an ancestor of modern humans. In 1938, at 70 years old, Broom was excavating at Kromdraai, South Africa and discovered pieces of a skull and teeth which resembled Dart's Australopithecus africanus find, but the skull had some "robust" characteristics.

The fossils included parts of a skull and teeth, all dated to 2 million years old. Sites with fossils of Paranthropus robustus are found only in South Africa, and include the sites of Kromdraai, Swartkrans, Drimolen, Gondolin and Coopers. In the cave at Swartkrans the remains of 130 individuals were discovered. The study made on the dentition of the hominins revealed that the average P. robustus rarely lived past 17 years of age.

Paranthropus robustus was the first discovery of a "robust" species of hominin; it was found well before P. boisei and P. aethiopicus. These three species have alternately been in their own (Paranthropus) or placed within the genus Australopithecus. This is partly because in many small details, the species robustus resembles A. africanus more than it does either of the other "robust" species, aethiopicus or boisei. Broom's discovery was the second australopithecine after Australopithecus africanus.

Morphology

Typical of robust australopithecines, P. robustus had a head shaped a bit like a gorilla's with a more massive built jaw and teeth in comparison to hominins within the Homo lineage. The sagittal crest that runs from the top of the skull acts as an anchor for large chewing muscles. The DNH 7 skull of Paranthropus robustus, "Eurydice",[1] was discovered in 1994 at the Drimolen Cave in Southern Africa by Andre Keyser, and is dated to 2.3 million years old, possibly belonging to a female.

The teeth of these primates were larger and thicker than any gracile australopithecine found, due to the morphology differences Broom originally designated his find as Australopithecus robustus. On the skull, a bony ridge is located above from the front to back indicating where the jaw muscles joined. P. robustus males may have stood only 1.2m (4 feet) tall and weighed 54 kg (120 lb) while females stood just under 1 meter (3 feet 2 inches) tall and weighed only 40 kg (90 lb), indicating a large sexual dimorphism. The teeth found on P. robustus are almost as large as those of P. boisei.

Broom analyzed his findings carefully and noted the differences in the molar teeth size which resembled a gorilla's a bit more than a human's. Other P. robustus remains have been found in Southern Africa. The average brain size of P. robustus measured to only 410 and 530 cc, about as large as a chimpanzee's. Some have argued that P robustus had a diet of hard gritty foods such as nuts and tubers since they lived in open woodland and savanna. More recent research suggests that this taxon was more of a dietary generalist,[2] and others have argued that they principally consumed hard and gritty resources as fallback foods only during time of nutritional stress.[3]

A 2011 study using ratios of strontium isotopes in teeth suggested that Australopithecus africanus and P. robustus groups in southern Africa were patrilocal: females tended to settle farther from their region of birth than males did.[4][5]

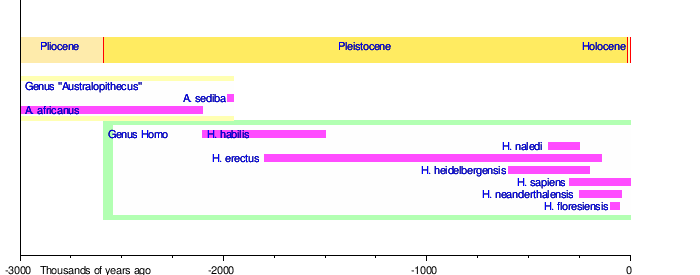

Development relative to other Hominins

|

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paranthropus robustus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Paranthropus robustus |

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

References

- ↑ Frisancho, Roberto (2006). Humankind Evolving: An Exploration of the Origins of Human Diversity. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. p. 135. ISBN 978-0757514081.

- ↑ Wood, B. & Strait, D. (2004). "Patterns of resource use in early Homo and Paranthropus". Journal of Human Evolution. 46 (2): 119–162. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2003.11.004. PMID 14871560.

- ↑ Scott, R.S.; Ungar, P.S.; Bergstrom, T.S.; Brown, C.A.; Grine, F.E.; Teaford, M.F. & Walker, A. (2005). "Dental microwear texture analysis shows within-species dietary variability in fossil hominins". Nature. 436 (7051): 693–695. doi:10.1038/nature03822. PMID 16079844.

- ↑ Bowdler, Neil (2 June 2011). "Ancient cave women 'left childhood homes'". BBC News. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ↑ Copeland SR, et al. (2011). "Strontium isotope evidence for landscape use by early hominins". Nature. 474 (7349): 76–78. doi:10.1038/nature10149. PMID 21637256.

External links

- MNSU

- Archaeology Info

- Paranthropus robustus - The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- Most complete ape-man skull found - but he is a she

- Researchers discuss ape-man fossil find

- Coopers Cave Home Page

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).