Prehistoric music

_(9420310527).jpg)

| Music eras | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

Prehistoric music (previously primitive music) is a term in the history of music for all music produced in preliterate cultures (prehistory), beginning somewhere in very late geological history. Prehistoric music is followed by ancient music in different parts of the world, but still exists in isolated areas. However, it is more common to refer to the "prehistoric" music which still survives as folk, indigenous or traditional music. Prehistoric music is studied alongside other periods within music archaeology.

Findings from Paleolithic archaeology sites suggest that prehistoric people used carving and piercing tools to create instruments. Archeologists have found Paleolithic flutes carved from bones in which lateral holes have been pierced. The Divje Babe flute, carved from a cave bear femur, is thought to be at least 40,000 years old. Instruments such as the seven-holed flute and various types of stringed instruments, such as the Ravanahatha, have been recovered from the Indus Valley Civilization archaeological sites.[1] India has one of the oldest musical traditions in the world—references to Indian classical music (marga) are found in the Vedas, ancient scriptures of the Hindu tradition.[2] The earliest and largest collection of prehistoric musical instruments was found in China and dates back to between 7000 and 6600 BCE.[3]

Origins

Some cultures have certain instances of their music intending to imitate natural sounds. In some instances, this feature is related to shamanistic beliefs or practice.[4][5] It may also serve entertainment (game)[6][7] or practical functions (for example, luring animals in hunt)[6].

Another possible origin of music is motherese, the vocal-gestural communication between mothers and infants. This form of communication involves melodic, rhythmic and movement patterns as well as the communication of intention and meaning, and in this sense is similar to music.[8]

Miller suggests musical displays play a role in "demonstrating fitness to mate". Based on the ideas of honest signal and the handicap principle, Miller suggested that music and dancing, as energetically costly activities, were to demonstrate the physical and psychological fitness of the singing and dancing individual to the prospective mates.[9]

Communal singing by both sexes occurs among cooperatively breeding songbirds of Australia and Africa such as magpies,[10], and white-browed sparrow weaver[11].

Prehistoric musical instruments

It is likely that the first musical instrument was the human voice itself, which can make a vast array of sounds, from singing, humming and whistling through to clicking, coughing and yawning. (See Darwin’s Origin of Species on music and speech.) The oldest known Neanderthal hyoid bone with the modern human form has been dated to be 60,000 years old,[12] predating the oldest known Paleolithic bone flute by some 20,000 years,[13] but the true chronology may date back much further.

Most likely the first rhythm instruments or percussion instruments involved the clapping of hands, stones hit together, or other things that are useful to create rhythm and there are examples of musical instruments which date back as far as the paleolithic, although there is some ambiguity [14] over archaeological finds which can be variously interpreted as either musical or non-musical instruments/tools. Examples of paleolithic objects which are considered unambiguously musical are bone flutes or pipes; paleolithic finds which are open to interpretation are pierced phalanges (usually interpreted as "phalangeal whistles"), objects interpreted as bullroarers, and rasps.

Music can be theoretically traced to prior to the Paleolithic age, the anthropological and archaeological designation suggests that music first arose (among humans) when stone tools first began to be used by hominids. The noises produced by work such as pounding seed and roots into meal is a likely source of rhythm created by early humans.

Flutes

The oldest flute ever discovered may be the so-called Nicholas flute, found in the Hohle Fels cave, Germany in 2008, though this is disputed.[15] The item in question is a fragment of the femur of a juvenile cave bear, and has been dated to about 43,000 years ago.[16][17] However, whether it is truly a musical instrument or simply a carnivore-chewed bone is a matter of ongoing debate.[15] In 2012 some flutes, that were discovered years earlier in the Geißenklösterle cave, received a new high-resolution carbon-dating examination yielding an age of 42,000 to 43,000 years.[18]

In 2008, archaeologists discovered a bone flute in the Hohle Fels cave near Ulm, Germany.[19][20] The five-holed flute has a V-shaped mouthpiece and is made from a vulture wing bone. The researchers involved in the discovery officially published their findings in the journal Nature in June 2009. It is one of several similar instruments found in the area, which date to at least 35,000 years ago, making this one of the oldest confirmed find of any musical instruments in history.[21] The Hohle Fels flute was found next to the Venus of Hohle Fels and a short distance from the oldest known human carving.[22] On announcing the discovery, scientists suggested that the "finds demonstrate the presence of a well-established musical tradition at the time when modern humans colonized Europe".[23] Scientists have also suggested that the discovery of the flute may help to explain why early humans survived, while Neanderthals became extinct.[21]

The oldest known wooden pipes were discovered in Wicklow, Ireland, in the winter of 2003. A wood-lined pit contained a group of six flutes made from yew wood, between 30 and 50 cm long, tapered at one end, but without any finger holes. They may once have been strapped together.[24]

In 1986, several gudi (literally "bone flutes") were found in Jiahu in Henan Province, China. They date to about 6000 BCE. They have between 5 and 8 holes each and were made from the hollow bones of a bird, the red-crowned crane. At the time of the discovery, one was found to be still playable. The bone flute plays both the five- or seven-note scale of Xia Zhi and six-note scale of Qing Shang of the ancient Chinese musical system.

Archaeoacoustic methodology

The use of the term 'music' is problematic within prehistory. It may be that, as in the traditional music of much of sub-Saharan Africa, the concept of 'music' as we understand it was somewhat different. Many languages traditionally have terms for music that include dance, religion or cult. The context in which prehistoric music took place has also become a subject of much study, as the sound made by music in prehistory would have been somewhat different depending on the acoustics present. The field of archaeoacoustics uses acoustic techniques to explore prehistoric sounds, soundscapes and instruments, and has included the study of ringing rocks and lithophones, of the acoustics of ritual sites such as chamber tombs and stone circles, and the exploration of prehistoric instruments using acoustic testing. Such work has included acoustic field tests to capture and analyse the impulse response of archaeological sites; acoustic tests of lithophones or 'rock gongs'; and reconstructions of soundscapes as experimental archaeology.

An academic research network, the Acoustics and Music of British Prehistory Research Network, has explored this field.

Cycladic culture

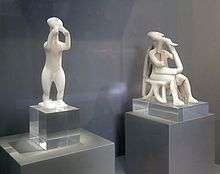

On the island of Keros (Κέρος), two marble statues from the late Neolithic culture called Early Cycladic culture (2900-2000 BCE) were discovered together in a single grave in the 19th century. They depict a standing double flute player and a sitting musician playing a triangular-shaped lyre or harp. The harpist is approximately 23 cm (9 in) high and dates to around 2700-2500 BCE. He expresses concentration and intense feelings and tilts his head up to the light. The meaning of these and many other figures is not known; perhaps they were used to ward off evil spirits or had religious significance or served as toys or depicted figures from mythology.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Music of India By Reginald MASSEY, Jamila MASSEY. Google Books

- ↑ Brown, RE (1971). "India's Music". Readings in Ethnomusicology.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Endymion (2000). Chinese history. Harvard University Asia Center.

- ↑ Hoppál 2006: 143 Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Diószegi 1960: 203

- 1 2 Nattiez: 5

- ↑ Deschênes 2002

- ↑ Dissanayake, E. (2000). Antecedents of the temporal arts in early mother-infant interaction. In The origins of music. Edited by Nils Wallin, Bjorn Merker and Steven Brown, pp. 389-410. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, pg 389-410

- ↑ Miller, G. (2000). Evolution of human music through sexual selection. In The origins of music. Edited by Nils Wallin, Bjorn Merker and Steven Brown, pp. 329-360. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, pg. 389-410

- ↑ Brown, Eleanor D. and Farabaugh, Susan M.; “Song Sharing in a Group-Living Songbird, the Australian Magpie, Gymnorhina tibicen. Part III. Sex Specificity and Individual Specificity of Vocal Parts in Communal Chorus and Duet Songs” in Behaviour, Vol. 118, No. 3/4 (September 1991), pp. 244-274

- ↑ Voigt, Cornelia; Leitner, Stefan and Gahr, Manfred; “Repertoire and structure of duet and solo songs in cooperatively breeding white-browed sparrow weavers” Archived 2007-06-28 at the Wayback Machine. in Behaviour; Vol. 143, No. 2 (February 2006), pp. 159-182

- ↑ B. Arensburg; A. M. Tillier; B. Vandermeersch; H. Duday; L. A. Schepartz; Y. Rak (April 1989). "A Middle Palaeolithic human hyoid bone". Nature. 338 (6218): 758–760. doi:10.1038/338758a0. PMID 2716823.

- ↑ http://blogs.discovermagazine.com

- ↑ http://www.dar.cam.ac.uk Archived 2007-07-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 d'Errico, Francesco, Paola Villa, Ana C. Pinto Llona, and Rosa Ruiz Idarraga (1998). "A Middle Palaeolithic origin of coool? Using cave-bear bone accumulations to assess the Divje Babe I bone 'flute'". Antiquity. 72 (March): 65–79. Archived from the original (Abstract) on 2012-12-22.

- ↑ Tenenbaum, David (June 2000). "Neanderthal jam". The Why Files. University of Wisconsin, Board of Regents. Retrieved 14 March 2006.

- ↑ Flute History, UCLA. Retrieved June 2007.

- ↑ Earliest music instruments found

- ↑ Wilford, John N. (June 24, 2009). "Flutes Offer Clues to Stone-Age Music". Nature. The New York Times. 459 (7244): 248–52. doi:10.1038/nature07995. PMID 19444215. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ↑ http://www.epoc.de/artikel/999323&_z=798890

- 1 2 "'Oldest musical instrument' found". BBC news. 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ "Music for cavemen". MSNBC. 2009-06-24. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ "Flutes Offer Clues to Stone-Age Music". The New York Times. 2009-06-24. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2012). "The Wicklow Pipes / The Development of Flutes in Europe and Asia". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2012-01-09.

References

- Deschênes, Bruno (2002). "Inuit Throat-Singing". Musical Traditions. The Magazine for Traditional Music Throughout the World.

- Diószegi, Vilmos (1960). Sámánok nyomában Szibéria földjén. Egy néprajzi kutatóút története (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. The book has been translated to English: Diószegi, Vilmos (1968). Tracing shamans in Siberia. The story of an ethnographical research expedition. Translated from Hungarian by Anita Rajkay Babó. Oosterhout: Anthropological Publications.

- Hoppál, Mihály (2006). "Music of Shamanic Healing" (PDF). In Gerhard Kilger. Macht Musik. Musik als Glück und Nutzen für das Leben. Köln: Wienand Verlag. ISBN 3-87909-865-4.

- Nattiez, Jean Jacques. "Inuit Games and Songs • Chants et Jeux des Inuit". Musiques & musiciens du monde • Musics & musicians of the world. Montreal: Research Group in Musical Semiotics, Faculty of Music, University of Montreal. . The songs are online available from the ethnopoetics website curated by Jerome Rothenberg.

- Steven Mithen, The Singing Neanderthals: the Origins of Music, Language, Mind and Body (2006).

- Sorce Keller, M. "Origini della musica", in Alberto Basso (eds.), Dizionario Enciclopedico Universale della Musica e dei Musicisti, Torino, UTET, III (1984), 494- 500.

- Parncutt, R (2009). "Prenatal and infant conditioning, the mother schema, and the origins of music and religion" (PDF). Musicae Scientiae, Special issue on Music and Evolution (Ed. O. Vitouch & O. Ladinig), 119-150. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05.

- Hagen, EH and; Hammerstein P (2009). "Did Neanderthals and other early humans sing? Seeking the biological roots of music in the loud calls of primates, lions, hyenas, and wolves" (PDF). Musicae Scientiae.

Further reading

- Ellen Hickmann, Anne D. Kilmer and Ricardo Eichmann, (ed.) Studies in Music Archaeology III, 2001, VML Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH., Germany ISBN 3-89646-640-2

- Wallin, Nils, Bjorn Merker, and Steven Brown, eds., The Origins of Music, (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA., 2000). ISBN 0-262-23206-5. Compilation of essays.

- Engel, Carl, The Music of the Most Ancient Nations, Wm. Reeves, 1929.

- Haik Vantoura, Suzanne (1976). The Music of the Bible Revealed ISBN 978-2-249-27102-1

- Nettl, Bruno (1956). Music in Primitive Culture. Harvard University Press.

- Sachs, Curt, The Rise of Music in the Ancient World, East and West, W.W. Norton, 1943.

- Sachs, Curt, The Wellsprings of Music, McGraw-Hill, 1965.

- Smith, Hermann, The World's Earliest Music, Wm. Reeves, 1904.

External links

- Ensemble Musica Romana: Music from Antiquity, Prehistoric music

- Prehistoric Music Ireland

- Sound sample and playing instructions for reconstructed bone flutes.

- Dr.Ann Buckely Publications

- Information about a supposed Neanderthal flute found in Slovenia - the article written by Dr. Ivan Turk who discovered it.

- The Carnyx, an ancient and magnificent war/ceremonial Horn

- Acoustics and Music of British Music Prehistory

- Hoppál, Mihály (2006). "Music of Shamanic Healing" (PDF). In Gerhard Kilger. Macht Musik. Musik als Glück und Nutzen für das Leben. Köln: Wienand Verlag. ISBN 3-87909-865-4.