Hazarajat

Coordinates: 34°49′00″N 67°49′00″E / 34.8167°N 67.8167°E

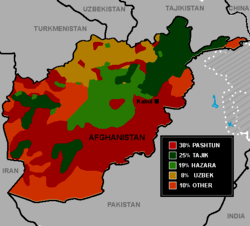

Hazarajat region shown within Afghanistan | |

| Area | Approx: 80,000 sq mi (207,199 km2) |

|---|---|

| Population | Approx: 8,000,000–10,000,000 |

| Density | 50/km2 (130/sq mi) |

| Provinces within Hazarajat | Bamyan, Daykundi, Ghor and large parts of Ghazni, Urozgan, Parwan and Wardak[1] |

| Ethnicities | Hazara, Tajik, Pashtun, Uzbek |

| Languages spoken | Hazaragi, Dari, Pashto, Uzbek |

| Part of a series on |

| Hazara people |

|---|

|

About · The people · The land · Language · Culture · Diaspora · Persecutions · Tribes · Cuisine Politics · Writers · Poets · Military · Religion · Sports · Battles |

Hazārajāt (Persian: هزارهجات) or Hazāristān (هزارستان)[2] is a region in the central highlands of Afghanistan, among the Koh-i-Baba mountains in the western extremities of the Hindu Kush. It is the homeland of the Hazara people who make up the majority of its population. "Hazārajāt denotes an ethnic and religious zone rather than a geographical one—that of Afghanistan's Turko-Mongol Shiʿites."[3] Hazarajat is primarily made up of the provinces of Bamyan, Daykundi, Ghor and large parts of Ghazni, Urozgan, Parwan and Wardak. The most populous towns in Hazarajat are Bamyan, Yakawlang (Bamyan), Nili (Daykundi), Lal wa Sarjangal (Ghor), Sang-e-Masha (Ghazni), Gizab (Urozgan) and Behsud (Wardak). The Kabul, Arghandab, Helmand, Farah, Hari, Murghab, Balkh and Kunduz rivers originate in Hazarajat.

The name "Hazarajat" first appears in the 16th-century book Baburnama, written by Mughal Emperor Babur (died 1530). When the famous geographer Ibn Battuta arrived in Afghanistan in 1333, he travelled across the country but did not record any place by the name of Hazarajat or any Hazara people.[4] It was not mentioned by previous geographers, historians, adventurers or invaders either.

Etymology and usage

The name Hazarajat is used by the Hazara people,[5] and surrounding peoples to identify the historic Hazara lands. The term might be linguistically compounded Hazara and the suffix jat; jat is a suffix that otherwise is used to make root words associated with land like Shumali Alaqa (JAT) Northern Areas in Pakistan, Dera (JAT) Dera Ghazi Khan and Dera Ismail Khan and other areas in South, central and west Asia.[6]

Maqdesi, an Arab geographer, named Hazarajat as Gharj Al-Shar-Gharj meaning "mountain" area ruled by chiefs. The region was known as Gharjistan in the late Middle Ages, though the exact locations of main cities still remain unidentified.[7][8] The name Hazarajat first appears in the 16th century Baburnama, written by Mughal Emperor Babur.

Geography

Topography

The Hazarajat lies in the central highlands of Afghanistan, among the Koh-i Baba mountains and the western extremities of the Hindu Kush. "Its boundaries have historically been inexact and shifting, and in some respects Hazārajāt denotes an ethnic and religious zone rather than a geographical one–that of Afghanistan’s Turko-Mongol Shiʿites. Its physical boundaries, however, are roughly marked by the Bā-miān Basin (see BĀMIĀN ii.) to the north, the headwaters of the Helmand River (q.v.) to the south, Firuzkuh to the west, and the Unai Pass to the east. The regional terrain is very mountainous and extends to the Safid Kuh and the Siāh Kuh mountains, where the highest peaks are between 15,000 to 17,000 feet. Both sides of the Kuh-e Bābā range contain a succession of valleys. The north face of the range descends steeply, merging into low foothills and short semi-arid plains, while the south face stretches towards the Helmand Valley and the mountainous district of Besud."[3][9]

Northwestern Hazarajat encompasses the district of Ghor, long known for its mountain fortresses. The 10th century geographer Estakhri wrote that mountainous Ghor was "the only region surrounded on all sides by Islamic territories and yet inhabited by infidels."[10] The long resistance of the inhabitants of Ghor to the adoption of Islam provides an indication of the region's inaccessibility; according to some travelers, the entire region is comparable to a fortress raised in the upper Central Asian highlands: from every approach, tall and steep mountains have to be traversed to reach there. The language of the inhabitants of Ghor differed so much from that of the people of the plains, that communication between the two required interpreters.[11]

The northeastern part of the Hazarajat, is the site of ancient Bamyan, a center of Buddhism and a key caravanserai on the Silk Road. The town is situated at a height of 7,500 feet and surrounded by the Hindu Kush to the north and Koh-i Baba to the south.[3] The Hazarajat was considered part of the larger geographic region of Khurasan (Kushan), the porous boundaries of which encompassed the vast region between the Caspian Sea and the Oxus River, thus including much of what is today Northern Iran and Afghanistan.[3]

Climate

Hazarajat is mountainous,[12] and a series of mountain passes extend along its eastern edge. One of them, Salang Pass, is blocked by snow six months out of the year. Another, Shibar Pass, at a lower elevation, is blocked by snow only two months out of the year.[13] Bamyan is the colder part of the region; winters there are severe.[14]

Hazarajat is the source of the rivers that run through Kabul, Arghandab, Helmand, Hari, Murghab, Balkh, and Kunduz, and during the spring and summer months, it has some of the greenest pastures in Afghanistan.[15] Natural lakes, green valleys and caves are found in Bamyan.[16]

History

The area was ruled successively by the Achaemenids, Seleucids, Mauryas, Kushans, and Hephthalites before the Saffarids Islamized it and made it part of their empire. It was taken over by the Samanids, followed by the Ghaznavids and Ghurids before falling to the Delhi Sultanate. In the 13th century, it was invaded by Genghis Khan and his Mongol army. In the following decades the Qarlughids emerged to create a short-lived local dynasty that offered a few decades of self-rule. Later, the area became part of the Timurid dynasty, the Mughal Empire and the Durrani Empire, successively.

When Alexander the Great travelled north into what is now Afghanistan, "his historians write that Alexander came across a strange people in the region who were more belligerent than the others. The description provided by Kent Corse about the mud houses of the people can be observed by any traveler today (Iranian Civilization, p. 422)." In the 7th century, Hsuen Tsang wrote "that a swift spring gushes from Ho-sa-la and its water divides into several branches. The weather of this place is cold and it snows and hails there. Its people are happy and free, they are skilled in magic craft and their language is different from the other lands."[17] It was reported that the Hephthalites ruled the area until they were conquered by the Ghaznavids in the 11th century.

Some contend that one of Genghis Khan's grandsons was killed by local fighters during the 1221 siege of Bamiyan. The story goes that Genghis Khan, enraged, then ordered his forces to annihilate the town and surrounding region, and that the Mongols formally laid a curse on the site. Later, the region remained a colony of the Ilkhanates, Chughtais, and others. Until 1333, there was no mention of Hazarajat or Hazara people in the region. Ibn Battuta described the area as being inhabited mostly by Persian-speaking people.[4]

The subjugation of the Hazarajat, particularly the mountain fortresses of Ghor, proved difficult for the Mongols after their conquest of the region, and ultimately Mongol military detachments left behind in the region "adopted the language of the vanquished".[18] In the late 14th century, Timur's armies made expeditions into Hazarajat, but Hazarajat was once again free after his death.[19] During Mongolian era, majority of Hazara were pastoralists dwelling in yurts and spoke Moghol. They started inhabiting the fortified villages, adopted a Persian dialect, and farming in the high steppes in the early 16th century. However, they kept flocks and some, on the norther slopes of Koh-i-Baba, remained nomadic and continued migrating between highland summer pastures and lowland winter pastures.[20]

19th century

In the 18th and 19th centuries, as a sense of "Afghan-ness" developed among the larger Sunni Pashtuns in Afghanistan, the Shia Hazara tribes began to coalesce.[21] It has been suggested that in the 19th century there was an emerging awareness of ethnic and religious differences among the population of Kabul. This brought about divisions along "confessional lines" that became reflected in new "spatial boundaries".[22] During the reign of Dost Mohammad Khan, Mir Yazdanbakhsh, a diligent chief of the Behsud Hazaras, consolidated many of the districts they controlled. Mir Yazdanbakhsh collected revenues and safeguarded caravans traveling on the Hajigak route through Bamyan to Kabul through Shaikh Ali and Besud areas. The consolidation of the Hazarajat thus increasingly made the region and its inhabitants a threat to the Durrani state.[23]

Until the late 19th century, the Hazarajat remained somewhat independent and only the authority of local chieftains was obeyed.[24] Joseph Pierre Ferrier, a French author who supposedly traveled through the region in the mid-19th century, described the inhabitants settled in the mountains near the rivers Balkh and Kholm "The Hazara population is ungovernable, and has no occupation but pillage; they will pillage and pillage only, and plunder from camp to camp".[25] Subsequent British travelers doubted whether Ferrier had ever actually left Herat to venture into Afghanistan’s central mountains and have suggested that his accounts of the region were based on hearsay, especially since very few people dared then to enter the Hazarajat; even Pashtun nomads would not take their flocks to graze there, and few caravans would pass through.[26]

Later in the early 1890s, the tribes of the Hazarajat were taxed and conscripted, while thousands were massacred. Afghanistan's Kuchi people, who are unsettled nomads who migrate between the Amu Darya and the Indus River, temporarily stayed in Hazarajat during some seasons, where they overran Hazara farmlands and pastures.[27] Increasingly during summers, these nomads would camp in large numbers in the Hazarajat highlands.

The travels of Captains P. J. Maitland and M. G. Talbot from Herat, through Obeh and Bamyan, to Balkh, during the autumn and winter of 1885, explored the Hazarajat proper. Maitland and Talbot found the entire length of the road between Herat and Bamyan difficult to traverse.[28] As a result of the expedition, parts of the Hazarajat were surveyed on one-eighth inch scale and thus made to fit into the mapped order of modern nation-states.[29] More thought and attention was put into demarcating the definite borders of modern nations than ever before, which entailed great difficulties in frontier regions such as the Hazarajat.

During the Second Anglo-Afghan War, Colonel T. H. Holdich of the Indian Survey Department referred to the Hazarajat as "great unknown highlands".[30] And for the next few years, neither the Survey nor the Indian Intelligence Department succeeded in obtaining any trustworthy information on the routes between Herat and Kabul through the Hazarajat.[31]

Various members of the Afghan Boundary Commission were able to gather information that brought the geography of remote regions such as the Hazarajat further under state surveillance. In November 1884, the Commission crossed over the Koh-i Baba mountains by the Chashma Sabz Pass. General Peter Lumsden and Major C. E. Yate, who surveyed the tracts between Herat and the Oxus, visited the Qala-e Naw Hazaras in the Paropamisus mountain range, to the east of the Jamshidis of Kushk. Noting surviving evidence of terraced cultivation in times past, both described the northern Hazaras as semi-nomadic with large flocks of sheep and black cattle. They possessed an "inexhaustible supply of grass, the hills around being covered knee-deep with a luxuriant crop of pure rye".[32] Yate noted clusters of kebetkas, or the summer dwellings of the Qala-e Naw Hazaras on the hillsides, and described "flocks and herds grazing in all directions".[33][34]

The geographical reach of the authority of the Afghan state was extended into the Hazarajat during the reign of Abdur Rahman Khan. Caught between the strategic interests of foreign powers and disappointed by the demarcation of the Durand Line in southern Afghanistan, which cut into Pashtun territory, he set out to bring the northern peripheries of the country more firmly under his control. This policy had disastrous consequences for the Hazarajat, whose inhabitants were singled out by Abdur Rahman Khan’s regime as particularly troublesome: "The Hazara people had been for centuries past the terror of the rulers of Kabul".[35]

20th and 21st century

In the 1920s the ancient Shibar Pass road which leads through Bamyan and east to the Panjshir Valley was paved for lorries, and it remained the busiest road across the Hindu Kush until the building of the Salang tunnel in 1964 and the opening of a winter route. The Hazarajat became increasingly depopulated as Hazaras migrated to cities and to surrounding countries, where they became laborers and undertook the hardest and lowest-paid work.[3]

In 1979, there were reportedly one and a half million Hazaras in the Hazarajat and Kabul.[36] As the Afghan state weakened, uprisings broke out in the Hazarajat, freeing the region from state rule by the summer of 1979 for the first time since the death of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan. Under the inspiration of the Iranian Revolution, various Hazara-Shiʿi resistance groups were formed in Iran, including Nasr and Sipah-i Pasdaran, with some being "committed to the idea of a separate Hazara national identity".[37] During the war with the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, most of the Hazarajat was unoccupied and free of Soviet or state presence. The region became ruled once again by local leaders, or mirs, and a new stratum of young radical Shiʿi commanders. Economic conditions are reported to have improved in the Hazarajat during the war, when Pashtun Kuchis stopped grazing their flocks in Hazara pastures and fields.[38]

The group ruling Hazarajat was the Revolutionary Council of Islamic Unity of Afghanistan or Shura-i Ettefaq, led by Sayyid Ali Beheshti, who created a de facto proto-state. The region's geographic nature and un-strategic location meant that the government and Soviets ignored it as they fought rebels elsewhere. This effectively allowed the Shura-i Ettefaq administration to rule over the region and give autonomy to the Hazaras. Their politically opposing groups were the pro-Iran Nasr and the Khans, who were mostly educated, secular and left-wing.[39] [40] The Shura wanted a return to the 19th century status quo whiereas the Nasr wanted an Iranian-style government of clerics. Between 1982 and 1984, an internal civil war caused the Shura to be overthrown by the Sazman-i Nasr and Sepah-i Pasdaran groups, which were backed by Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran in his efforts for (Shia) Iranian influence in Afghanistan. However inter-factional rivalry continued thereafter. Most of the Hazara groups united in 1987 and in 1989 formed the Hizb-i-Wahdat.[41]

During the rule of Taliban, once again, ethnic and sectarian violence struck Hazarajat. In 1997, a revolt broke out among Hazara people in Mazar-i-Sharif when refused to be disarmed by Taliban; 600 Taliban were killed in subsequent fighting.[42] In retaliation, the genocidal policies of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan's era was adopted by Taliban. In 1998, six thousand Hazaras were killed in the north; the intention was ethnic cleansing of Hazara.[43] At that stage, Hazarajat did not exist as an official region; the area was divided between the administrative provinces of Bamyan, Ghor, Wardak, Ghazni, Oruzgan, Juzjan, and Samangan, with the Hazaras being a minority in each.[38]

Demographics

Ethnic groups

Afghanistan is a multiethnic society with a variety of ethnolinguistic groups. Because of poor census exact figures about the size and composition of ethnic groups are not available. According to the 2015 estimation, Pashtun is the largest ethnic group at 38% of the total population of the country followed by Tajik at 25%, Hazara at 19%, Uzbek at 8%, Aimaq at 4%, Turkmen at 3%, Baloch at 4%, and other groups that make up 4%.[44] The Afghan National Anthem mentions 14 different ethnic groups.

A research poll was conducted in Afghanistan in 2009, where 72% of the population labeled their identity as Afghan despite of being from different ethnic groups.[45]

.jpg)

Language

The history of the language in Hazarajat has been an issue of debate. In the 16th century, when Babur came to Afghanistan, some Hazara spoke Mongolian language, writers like Bacon[46] and Schumann[47] believed the original language of Hazara people was Persian. According to Dulling, on the other hand, the Hazaras' language was a mixture of Persian and Hindi, in which Persian took over Hindi in Middle Ages.[48] In the late 19th century, Hazaragi, a distinct Persian dialect, began to emerge among the people of Hazarajat. It remains uncertain when Mongolian died out as a living language. Dulling writes, "they ceased to be Mongol speakers by the end of the 18th century at the latest, and were then speaking Tajik of a sort".[49] Dari is the official language in Hazarajat.

Religion

Islam was established in Bamyan, Ghor and other parts of Hazarajat, during the rule of Ghaznavid dynasty in the 11th century.[3] W. Barthold states that "the only region surrounded on all sides by Islamic territories and yet inhabited by infidels"[50] was Hazarajat. Probably, most of Hazarajat was Sunni and converted to Shi'ism during the Safavid era. Some believe that traces of Shi'ism can be dated back to Ilkhanate period. Most are Twelver Shias, but there are also Sunni Aimaks.[51]

Health

Leprosy has been reported in the Hazarajat region of Afghanistan. The vast majority (80%) of the leprosy victims are Hazara.[52] In 1999, Leprosy Control stated that they were the only NGO providing anti-leprosy aid in the Hazarajat, and had been doing so since 1984.

A 1989 report noted that common diseases in the Hazarajat included gastrointestinal infections, typhoid, whooping cough, measles, leprosy, tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis and malaria.[53]

See also

References

- ↑ "Bamyan Province". Naval Postgraduate School. 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ – Some Hazara prefer to call the area Hazaristan, using the more modern "istan" ending.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Arash Khazeni. "HAZĀRA i. Historical geography of Hazārajāt". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- 1 2 Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325–1354 (reprint, illustrated ed.). Routledge. 2004. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-415-34473-9. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Bellew, H.W. (1880). The Races of Afghanistan: Being a Brief Account of the Principal Nations Inhabiting that Country. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co. p. 114.

- ↑ Mousavi, S.A. (1998). The Hazaras of Afghanistan: An Historical, Cultural, Economic and Political Study. Richmond, Surrey UK: Curzon Press. p. 34. ISBN 0-7007-0630-5.

- ↑ Ḥamd-Allah Mostawfi, Nozhat al-qolub, tr. Guy Le Strange, London 1919. pp 415–16

- ↑ S. A. Mousavi, The Hazaras of Afghanistan, London, 1998, p. 39

- ↑ Wilfred Thesiger "The Hazaras of Central Afghanistan," The Geographical Journal 71/3, 1955, pp. 313

- ↑ W. Barthold, An Historical Geography of Iran, Princeton, 1984, p. 51

- ↑ W. Barthold, An Historical Geography of Iran, Princeton, 1984, p. 52

- ↑ Anonymous, Ḥodud al-ʿālam, tr. Minorsky, London, 1937; reprinted, 1982, p. 105

- ↑ Johannes Humlum, La geographie de l’Afghanistan, Copenhagen, 1959, p. 64

- ↑ Ebn Ḥawqal, Ke-tāb ṣurat al-arż, trs. J. H. Kramers and G. Wiet as Configuration de la terre, II, Paris, 1964, p. 227

- ↑ Ḥamd-Allah Mostawfi, Nozhat al-qolub, tr. Guy Le Strange, London 1919, p. 212

- ↑ S. A. Mousavi, The Hazaras of Afghanistan, London, 1998, p. 71

- ↑ "Is Hazara An Ancient Word?". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ W. Barthold, An Historical Geography of Iran, Princeton, 1984, p. 82

- ↑ J. P. Ferrier, Caravan Journeys and Wanderings in Persia, Afghanistan, Turkestan, and Beloochistan, London, 1856, p. 221

- ↑ Johannes Humlum, La geographie de l’Afghanistan, Copenhagen, 1959, p. 87

- ↑ Robert L. Canfield, Hazara Integration into the Afghan Nation, New York, 1973, p. 3

- ↑ Christine Noelle, State and Tribe in Nineteenth-Century Afghanistan, Richmond, 1997, p. 22

- ↑ C. Masson, Narrative of Various Journeys in Baloochistan, Afghanistan, and the Punjab. London, 1842, II, p. 296

- ↑ W. Barthold, An Historical Geography of Iran, Princeton, 1984, pp. 82–83

- ↑ J. P. Ferrier, Caravan Journeys and Wanderings in Persia, Afghanistan, Turkestan, and Beloochistan, London, 1856, pp. 219–20

- ↑ Klaus Ferdinand, Preliminary Notes on Hazāra Culture, Copenhagen, 1959,p. 18

- ↑ S. A. Mousavi, The Hazaras of Afghanistan, London, 1998, p. 95

- ↑ Anonymous, "Captain Maitland’s and Captain Talbot’s Journeys in Afghanistan," Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society 9, 1887 p. 103

- ↑ Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, London, 1991 [1983], pp. 170–78

- ↑ T. H. Holdich, The Indian Borderland, 1880–1900, London, 1901, p. 41

- ↑ A. C. Yate, Travels with the Afghan Boundary Commission, Edinburgh, 1887 pp. 147–48

- ↑ C. E. Yate, Northern Afghanistan, Edinburgh, 1888, p. 9

- ↑ C. E. Yate, Northern Afghanistan, Edinburgh, 1888, pp. 7–8

- ↑ Peter Lumsden, "Countries and Tribes bordering on the Koh-e Baba Range," Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society 7, 1885, pp. 562–63

- ↑ Mir Munshi, ed., The Life of Abdur Rahman, Amir of Afghanistan, II, London, 1900, p. 276

- ↑ Barnett Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, New Haven, 2002, p. 26

- ↑ Barnett Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, New Haven, 2002. pp. 186, 191, 223

- 1 2 Barnett Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, New Haven, 2002, p. 246

- ↑ citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.604.3516&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- ↑ Nation, Ethnicity and the Conflict in Afghanistan: Political Islam and the rise of ethno-politics 1992–1996 by Raghav Sharma, 2016.

- ↑ Nation, Ethnicity and the Conflict in Afghanistan: Political Islam and the rise of ethno-politics 1992–1996 by Raghav Sharma, 2016.

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil, and Fundamentalism in Central Asia, London and New Haven, 2000, p. 58

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil, and Fundamentalism in Central Asia, London and New Haven, 2000, pp. 67–74

- ↑ "Afghanistan" (PDF). Civil Military Fusion Centre. Wiebke Lamer and Erin Foster (US Department of State). Retrieved 2011-08. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ ABC NEWS/BBC/ARD POLL – AFGHANISTAN: WHERE THINGS STAND, February 9th, 2009, p. 38–40

- ↑ Bacon E: The Hazara Mongols of Afghanistan: A study in social organization, PhD Dissertation, University of California, 1951, page 6.

- ↑ H.F. Schurmann: The Mongols of Afghanistan: an ethnography of the Mongols and related people of Afghanistan, University of California 1962, page 25-26

- ↑ Dulling G. K.: The Hazaragi Dialect of Afghan Persian, Central Asian Research Center, London 1973, page 47

- ↑ Dulling G.K. The Hazaragi Dialect of Afghan Persian. London, Central Asian Research Center 1973:13

- ↑ W. Barthold, An Historical Geography of Iran, Princeton, 1984, p. 51

- ↑ S. A. Mousavi, The Hazaras of Afghanistan, London, 1998, pp. 73–76

- ↑ Dr. Mohammad Salim Rasooli. Leprosy Situation in Afghanistan in 2001–2006 Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine.. Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) National Leprosy Control Program. 7–9 July 2008.

- ↑ Hassan Poladi (February 1989). The Hazāras. Mughal Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-929824-00-0. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hazarajat. |