Herat

| Herat هرات | |

|---|---|

| City | |

From top: Overview of Herat city; The Friday Mosque; Citadel of Herat | |

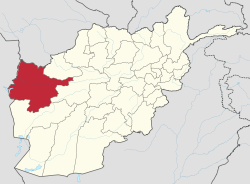

Herat Location in Afghanistan | |

| Coordinates: 34°20′31″N 62°12′11″E / 34.34194°N 62.20306°ECoordinates: 34°20′31″N 62°12′11″E / 34.34194°N 62.20306°E | |

| Country |

|

| Province | Herat |

| Area | |

| • Total | 182 km2 (70 sq mi) |

| [1] | |

| Elevation | 920 m (3,020 ft) |

| Population [2] | |

| • Total | 436,300 |

| • Density | 2,400/km2 (6,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+4:30 (Afghanistan Standard Time) |

| Climate | BSk |

Herat (/hɛˈrɑːt/;[3] Persian: هرات,Harât ,Herât; Pashto: هرات; Ancient Greek: Ἀλεξάνδρεια ἡ ἐν Ἀρίοις, Alexándreia hē en Aríois; Latin: Alexandria Ariorum) is the third-largest city of Afghanistan. It has a population of about 436,300,[2] and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated in the fertile valley of the Hari River. It is linked with Kandahar and Mazar-e-Sharif via Highway 1 or the ring road. It is further linked to the city of Mashhad in neighboring Iran through the border town of Islam Qala, and to Turkmenistan through the border town of Torghundi, both about 100 km (62 mi) away.

Herat dates back to the Avestan times and was traditionally known for its wine. The city has a number of historic sites, including the Herat Citadel and the Musalla Complex. During the Middle Ages Herat became one of the important cities of Khorasan, as it was known as the Pearl of Khorasan.[4] It has been governed by various Afghan rulers since the early 18th century.[5] In 1717, the city was invaded by the Hotaki forces until they were expelled by the Afsharids in 1729. After Nader Shah's death and Ahmad Shah Durrani's rise to power in 1747, Herat became part of Afghanistan.[5] It witnessed some political disturbances and military invasions during the early half of the 19th century but the 1857 Treaty of Paris ended hostilities of the Anglo-Persian War.[6]

Herat lies on the ancient trade routes of the Middle East, Central and South Asia, and today is a regional hub in western Afghanistan. The roads from Herat to Iran, Turkmenistan, and other parts of Afghanistan are still strategically important. As the gateway to Iran, it collects high amount of customs revenue for Afghanistan.[7] It also has an international airport. The city has high residential density clustered around the core of the city. However, vacant plots account for a higher percentage of the city (21%) than residential land use (18%) and agricultural is the largest percentage of total land use (36%).[8] Today the city is considered to be relatively safe.[9]

History

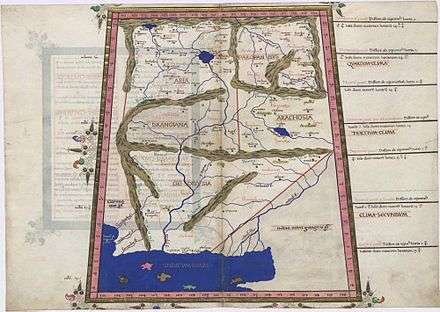

Herat dates back to ancient times (its exact age remains unknown). During the period of the Achaemenid Empire (ca. 550-330 BC), the surrounding district was known as Haraiva (in Old Persian), and in classical sources the region was correspondingly known as Aria (Areia). In the Zoroastrian Avesta, the district is mentioned as Haroiva. The name of the district and its main town is derived from that of the chief river of the region, the Herey River (Old Dari Hereyrud, "Silken Water"), which traverses the district and passes some 5 km (3.1 mi) south of modern Herāt. Herey is mentioned in Sanskrit as yellow or golden color equivalent to Persian "Zard" meaning Gold (yellow). The naming of a region and its principal town after the main river is a common feature in this part of the world—compare the adjoining districts/rivers/towns of Arachosia and Bactria.

The district Aria of the Achaemenid Empire is mentioned in the provincial lists that are included in various royal inscriptions, for instance, in the Behistun inscription of Darius I (ca. 520 BC).[10] Representatives from the district are depicted in reliefs, e.g., at the royal Achaemenid tombs of Naqsh-e Rustam and Persepolis. They are wearing Scythian-style dress (with a tunic and trousers tucked into high boots) and a twisted Bashlyk that covers their head, chin and neck.[11]

Hamdallah Mustawfi, composer of the 14th century work The Geographical Part of the Nuzhat-al-Qulub writes that:

Herāt was the name of one of the chiefs among the followers of the hero Narīmān, and it was he who first founded the city. After it had fallen to ruin Alexander the Great rebuilt it, and the circuit of its walls was 9000 paces.[4]

Herodotus described Herat as the bread-basket of Central Asia. At the time of Alexander the Great in 330 BC, Aria was obviously an important district. It was administered by a satrap called Satibarzanes, who was one of the three main Persian officials in the East of the Empire, together with the satrap Bessus of Bactria and Barsaentes of Arachosia. In late 330 BC, Alexander captured the Arian capital that was called Artacoana. The town was rebuilt and the citadel was constructed. Afghanistan became part of the Seleucid Empire after Alexander died, which formed an alliance with the Indian Maurya Empire. Roman Historian Strabo writes that the Seleucids later gave the area south of the Hindu Kush to the Mauryas after a treaty was made.

Alexander took these away from the Aryans and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.[12]

However, most sources suggest that Herat was predominantly Zoroastrian. It became part of the Parthian Empire in 167 BC. In the Sasanian period (226-652), Harēv is listed in an inscription on the Ka'ba-i Zartosht at Naqsh-e Rustam; and Hariy is mentioned in the Pahlavi catalogue of the provincial capitals of the empire. In around 430, the town is also listed as having a Christian community, with a Nestorian bishop.[13]

In the last two centuries of Sasanian rule, Aria (Herat) had great strategic importance in the endless wars between the Sasanians, the Chionites and the Hephthalites who had been settled in the northern section of Afghanistan since the late 4th century.

Islamization

At the time of the Arab invasion in the middle of the 7th century, the Sasanian central power seemed already largely nominal in the province in contrast with the role of the Hephthalites tribal lords, who were settled in the Herat region and in the neighboring districts, mainly in pastoral Bādghis and in Qohestān. It must be underlined, however, that Herat remained one of the three Sasanian mint centers in the east, the other two being Balkh and Marv. The Hephthalites from Herat and some unidentified Turks opposed the Arab forces in a battle of Qohestān in 651-52 AD, trying to block their advance on Nishāpur, but they were defeated

When the Arab armies appeared in Khorāsān in the 650s AD, Herāt was counted among the twelve capital towns of the Sasanian Empire. The Arab army under the general command of Ahnaf ibn Qais in its conquest of Khorāsān in 652 seems to have avoided Herāt, but it can be assumed that the city eventually submitted to the Arabs, since shortly afterwards an Arab governor is mentioned there. A treaty was drawn in which the regions of Bādghis and Bushanj were included. As did many other places in Khorāsān, Herāt rebelled and had to be re-conquered several times.[14]

Another power that was active in the area in the 650s was Tang dynasty China which had embarked on a campaign that culminated in the Conquest of the Western Turks. By 659-661, the Tang claimed a tenuous suzerainty over Herat, the westernmost point of Chinese power in its long history. This hold however would be ephemeral with local Turkish tribes rising in rebellion in 665 and driving out the Tang.[15]

In 702 AD Yazid ibn al-Muhallab defeated certain Arab rebels, followers of Ibn al-Ash'ath, and forced them out of Herat. The city was the scene of conflicts between different groups of Muslims and Arab tribes in the disorders leading to the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate. Herat was also a centre of the followers of Ustadh Sis.

In 870 AD, Yaqub ibn Layth Saffari, a local ruler of the Saffarid dynasty conquered Herat and the rest of the nearby regions in the name of Islam.

...Arab armies carrying the banner of Islam came out of the west to defeat the Sasanians in 642 AD and then they marched with confidence to the east. On the western periphery of the Afghan area the princes of Herat and Seistan gave way to rule by Arab governors but in the east, in the mountains, cities submitted only to rise in revolt and the hastily converted returned to their old beliefs once the armies passed. The harshness and avariciousness of Arab rule produced such unrest, however, that once the waning power of the Caliphate became apparent, native rulers once again established themselves independent. Among these the Saffarids of Seistan shone briefly in the Afghan area. The fanatic founder of this dynasty, the coppersmith's apprentice Yaqub ibn Layth Saffari, came forth from his capital at Zaranj in 870 AD and marched through Bost, Kandahar, Ghazni, Kabul, Bamiyan, Balkh and Herat, conquering in the name of Islam.[16]

Pearl of Khorasan

The region of Herāt was under the rule of King Nuh III, the seventh of the Samanid line—at the time of Sebük Tigin and his older son, Mahmud of Ghazni.[17] The governor of Herāt was a noble by the name of Faik, who was appointed by Nuh III. It is said that Faik was a powerful, but insubordinate governor of Nuh III; and had been punished by Nuh III. Faik made overtures to Bogra Khan and Ughar Khan of Khorasan. Bogra Khan answered Faik's call, came to Herāt and became its ruler. The Samanids fled, betrayed at the hands of Faik to whom the defence of Herāt had been entrusted by Nuh III.[17] In 994, Nuh III invited Alp Tigin to come to his aid. Alp Tigin, along with Mahmud of Ghazni, defeated Faik and annexed Herāt, Nishapur and Tous.[17]

Herat was a great trading centre strategically located on trade routes from Mediterranean to India or to China. The city was noted for its textiles during the Abbasid Caliphate, according to many references by geographers. Herāt also had many learned sons such as Ansārī. The city is described by Estakhri and Ibn Hawqal in the 10th century as a prosperous town surrounded by strong walls with plenty of water sources, extensive suburbs, an inner citadel, a congregational mosque, and four gates, each gate opening to a thriving market place. The government building was outside the city at a distance of about a mile in a place called Khorāsānābād. A church was still visible in the countryside northeast of the town on the road to Balkh, and farther away on a hilltop stood a flourishing fire temple, called Sereshk, or Arshak according to Mustawfi.[4][19][20][21][22]

Herat was a part of the Taherid dominion in Khorāsān until the rise of the Saffarids in Sistān under Ya'qub-i Laith in 861, who, in 862, started launching raids on Herat before besieging and capturing it on 16 August 867, and again in 872. The Saffarids succeeded in expelling the Taherids from Khorasan in 873.

The Sāmānid dynasty was established in Transoxiana by three brothers, Nuh, Yahyā, and Ahmad. Ahmad Sāmāni opened the way for the Samanid dynasty to the conquest of Khorāsān, including Herāt, which they were to rule for one century. The centralized Samanid administration served as a model for later dynasties. The Samanid power was destroyed in 999 by the Qarakhanids, who were advancing on Transoxiana from the northeast, and by the Ghaznavids, former Samanid retainers, attacking from the southeast.

Sultan Maḥmud of Ghazni officially took control of Khorāsān in 998. Herat was one of the six Ghaznavid mints in the region. In 1040, Herat was captured by the Seljuk Empire. Yet, in 1175, it was captured by the Ghurids of Ghor and then came under the Khawarazm Empire in 1214. According to the account of Mustawfi, Herat flourished especially under the Ghurid dynasty in the 12th century. Mustawfi reported that there were "359 colleges in Herat, 12,000 shops all fully occupied, 6,000 bath-houses; besides caravanserais and mills, also a darwish convent and a fire temple". There were about 444,000 houses occupied by a settled population. The men were described as "warlike and carry arms", and they were Sunni Muslims.[4] The great mosque of Herāt was built by Ghiyas ad-Din Ghori in 1201. In this period Herāt became an important center for the production of metal goods, especially in bronze, often decorated with elaborate inlays in precious metals.

Herat was invaded and destroyed by Genghis Khan's Mongol army in 1221. The city was destroyed a second time and remained in ruins from 1222 to about 1236. In 1244 a local prince Shams al-Din Kart was named ruler of Herāt by the Mongol governor of Khorāsān and in 1255 he was confirmed in his rule by the founder of the Il-Khan dynasty Hulagu. Shams al-Din founded a new dynasty and his successors, especially Fakhr-al-Din and Ghiyath al-Din, built many mosques and other buildings. The members of this dynasty were great patrons of literature and the arts. By this time Herāt became known as the pearl of Khorasan.

If any one ask thee which is the pleasantest of cities, Thou mayest answer him aright that it is Herāt. For the world is like the sea, and the province of Khurāsān like a pearl-oyster therein, The city of Herāt being as the pearl in the middle of the oyster.[4]

— Rumi, 1207–1273 A.D.

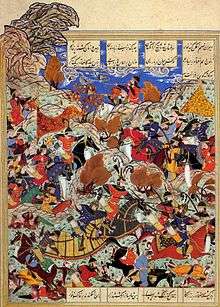

Timur took Herat in 1380 and he brought the Kartid dynasty to an end a few years later. The city reached its greatest glory under the Timurid princes, especially Sultan Husayn Bayqara who ruled Herat from 1469 until May 4, 1506. His chief minister, the poet and author in Persian and Turkish, Mir Ali-Shir Nava'i was a great builder and patron of the arts. Under the Timurids, Herat assumed the role of the main capital of an empire that extended in the West as far as central Persia. As the capital of the Timurid empire, it boasted many fine religious buildings and was famous for its sumptuous court life and musical performance and its tradition of miniature paintings. On the whole, the period was one of relative stability, prosperity, and development of economy and cultural activities. It began with the nomination of Shahrokh, the youngest son of Timur, as governor of Herat in 1397. The reign of Shahrokh in Herat was marked by intense royal patronage, building activities, and promotion of manufacturing and trade, especially through the restoration and enlargement of the Herat's bāzār. The present Musallah Complex, and many buildings such as the madrasa of Goharshad, Ali Shir mahāl, many gardens, and others, date from this time. The village of Gazar Gah, over two km northeast of Herat, contained a shrine which was enlarged and embellished under the Timurids. The tomb of the poet and mystic Khwājah Abdullāh Ansārī (d. 1088), was first rebuilt by Shahrokh about 1425, and other famous men were buried in the shrine area. Herat was shortly captured by Kara Koyunlu between 1458–1459.[23]

In 1507 Herat was occupied by the Uzbeks but after much fighting the city was taken by Shah Isma'il, the founder of the Safavid dynasty, in 1510 and the Shamlu Qizilbash assumed the governorship of the area. Under the Safavids, Herat was again relegated to the position of a provincial capital, albeit one of a particular importance. At the death of Shah Isma'il the Uzbeks again took Herat and held it until Shah Tahmasp retook it in 1528. The Persian king, Abbas was born in Herat, and in Safavid texts, Herat is referred to as a'zam-i bilād-i īrān, meaning "the greatest of the cities of Iran".[24] In the 16th century, all future Safavid rulers, from Tahamsp I to Abbas I, were governors of Herat in their youth.[25]

Modern history

By the early 18th century Herat was governed by various Hotaki and Abdali Afghans. After Nader Shah's death in 1747, Ahmad Shah Durrani took possession of the city and became part of the Durrani Empire.[5]

In 1824, Herat became independent for several years when the Afghan Empire was split between the Durranis and Barakzais. The Persians invaded the city in 1838, but the British helped the Afghans in repelling them. In 1856, they invaded again, and briefly managed to retake the city; it led directly to the Anglo-Persian War. In 1857 hostilities between the Persians and the British ended after the Treaty of Paris was signed, and the Persian troops withdrew from Herat.[26]

One of the greatest tragedies for the Afghans and Muslims was the British invasion of, and subsequent destruction of the Islamic Musallah complex in Herat in 1885. The officially stated reason was to get a good line of sight for their artillery against Russian invaders who never came. This was but one small sidetrack in the Great Game, a century-long conflict between the British Empire and the Russian Empire in 19th century.

_-_panoramio.jpg)

In the 1960s, engineers from the United States built Herat Airport, which was used by the Soviet forces during the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan in the 1980s. Even before the Soviet invasion at the end of 1979, there was a substantial presence of Soviet advisors in the city with their families.

Between March 10 and March 20, 1979, the Afghan Army in Herāt under the control of commander Ismail Khan mutinied. Thousands of protesters took to the streets against the Khalq communist regime's oppression led by Nur Mohammad Taraki. The new rebels led by Khan managed to oust the communists and take control of the city for 3 days, with some protesters murdering any Soviet advisers. This shocked the government, who blamed the new administration of Iran following the Iranian Revolution for influencing the uprising.[27] Reprisals by the government followed, and between 3,000 and 24,000 people (according to different sources) were killed, in what is called the 1979 Herat uprising, or in Persian as the Qiam-e Herat.[28] The city itself was recaptured with tanks and airborne forces, but at the cost of thousands of civilians killed. This massacre was the first of its kind since the country's independence in 1919, and was the bloodiest event preceding the Soviet–Afghan War.[29]

Herat received damage during the Soviet–Afghan War in the 1980s, especially its western side. The province as a whole was one of the worst-hit. In April 1983, a series of Soviet bombings damaged half of the city and killed around 3,000 civilians, described as "extremely heavy, brutal and prolonged".[30] Ismail Khan was the leading mujahideen commander in Herāt fighting against the Soviet-backed government.

After the communist government's collapse in 1992, Khan joined the new government and he became governor of Herat Province. The city was relatively safe and it was recovering and rebuilding from the damage caused in the Soviet–Afghan War.[31] However, on September 5, 1995, the city was captured by the Taliban without much resistance, forcing Khan to flee. Herat became the first Persian-speaking city to be captured by the Taliban. The Taliban's strict enforcement of laws confining women at home and closing girls' schools alienated Heratis who are traditionally more liberal and educated, like the Kabulis, than other urban populations in the country. Two days of anti-Taliban protests occurred in December 1996 which was violently dispersed and led to the imposition of a curfew.[32]

After the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, on November 12, 2001, it was captured from the Taliban by forces loyal to the Northern Alliance and Ismail Khan returned to power (see Battle of Herat). In 2004, Mirwais Sadiq, Aviation Minister of Afghanistan and the son of Ismail Khan, was ambushed and killed in Herāt by a local rival group. More than 200 people were arrested under suspicion of involvement.[33]

In 2005, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) began establishing bases in and around the city. Its main mission was to train the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and help with the rebuilding process of the country. Regional Command West, led by Italy, assisted the Afghan National Army (ANA) 207th Corps. Herat was one of the first seven areas that transitioned security responsibility from NATO to Afghanistan. In July 2011, the Afghan security forces assumed security responsibility from NATO.

Due to their close relations, Iran began investing in the development of Herat's power, economy and education sectors.[34] In the meantime, the United States built a consulate in Herat to help further strengthen its relations with Afghanistan. In addition to the usual services, the consulate works with the local officials on development projects and with security issues in the region.[35]

Geography

Climate

Herat has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk). Precipitation is very low, and mostly falls in winter. Although Herāt is approximately 240 m (790 ft) lower than Kandahar, the summer climate is more temperate, and the climate throughout the year is far from disagreeable, although winter temperatures are comparably lower. From May to September, the wind blows from the northwest with great force. The winter is tolerably mild; snow melts as it falls, and even on the mountains does not lie long. Three years out of four it does not freeze hard enough for the people to store ice. The eastern reaches of the Hari River, including the rapids, are frozen hard in the winter, and people travel on it as on a road.

| Climate data for Herāt | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.4 (75.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

37.8 (100) |

39.7 (103.5) |

44.6 (112.3) |

50.0 (122) |

42.7 (108.9) |

39.3 (102.7) |

37.0 (98.6) |

30.0 (86) |

26.5 (79.7) |

50 (122) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

35.0 (95) |

36.7 (98.1) |

35.1 (95.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

25.0 (77) |

17.8 (64) |

12.0 (53.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.2 (81) |

29.8 (85.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

22.9 (73.2) |

16.1 (61) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

8.5 (47.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.7 (−16.1) |

−20.5 (−4.9) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

0.8 (33.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−12.8 (9) |

−22.7 (−8.9) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51.6 (2.031) |

44.8 (1.764) |

55.1 (2.169) |

29.2 (1.15) |

9.8 (0.386) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

1.7 (0.067) |

10.9 (0.429) |

35.8 (1.409) |

238.9 (9.405) |

| Average rainy days | 6 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 40 |

| Average snowy days | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 69 | 62 | 56 | 45 | 34 | 30 | 30 | 34 | 42 | 55 | 67 | 50 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 149.3 | 153.5 | 202.5 | 235.7 | 329.6 | 362.6 | 378.6 | 344.8 | 323.2 | 274.0 | 235.0 | 143.1 | 3,131.9 |

| Source: NOAA (1959–1983)[36] | |||||||||||||

Places of interest

- Foreign consulates

India, Iran and Pakistan operate their consulate here for trade, military and political links.

- Neighborhoods

- Shahr-e Naw (Downtown)

- Welayat (Office of the governor)

- Qol-Ordue (Army's HQ)

- Farqa (Army's HQ)

- Darwaze Khosh

- Chaharsu

- Pul-e rangine

- Sufi-abad

- New-abad

- Pul-e malaan

- Thakhte Safar

- Howz-e-Karbas

- Baramaan

- Darwaze-ye Qandahar

- Darwaze-ye Iraq

- Darwaze Az Kordestan

- Parks

- Park-e Taraki

- Park-e Millat

- Khane-ye Jihad Park

- Monuments

- Herat Citadel (Qala Ikhtyaruddin or Arg)

- Musallah Complex

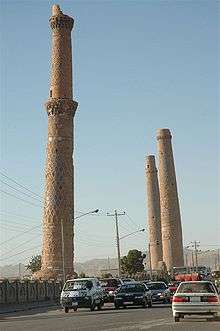

- Musalla Minarets of Herat

Of the more than dozen minarets that once stood in Herāt, many have been toppled from war and neglect over the past century. Recently, however, everyday traffic threatens many of the remaining unique towers by shaking the very foundations they stand on. Cars and trucks that drive on a road encircling the ancient city rumble the ground every time they pass these historic structures. UNESCO personnel and Afghan authorities have been working to stabilize the Fifth Minaret.[37][38]

- Museums

- Herat Museum, located inside the Herat Citadel

- Jihad Museum

- Mausoleums and tombs

- Mausoleum of Queen Goharshad

- Mausoleum of Khwajah Abdullah Ansari

- Tomb of Jami

- Tomb of khaje Qaltan

- Mausoleum of Mirwais Sadiq

- Jewish cemetery – there once existed an ancient Jewish community in the city. Its remnants are a cemetery and a ruined shrine.[39]

- Mosques

- Jumu'ah Mosque (Friday Mosque of Herat)

- Gazargah Sharif

- Khalghe Sharif

- Shah Zahdahe

- Hotels

- Serena Hotel (coming soon)

- Diamond Hotel

- Marcopolo Hotel

- Stadiums

- Herat Stadium

- Universities

Demography

The population of Herat numbers approximately 436,300 as of 2013.[2] It is a multi-ethnic society with Persian-speakers as the majority.[40] There is no current data on the precise ethnic make-over but according to a 2003 map found in the National Geographic Magazine, the percentage figure of ethnic groups was given as follows: 54% Tajik, 41% Pashtuns, 2% Hazaras, 2% Uzbeks and 1% Turkmens.[41]

Persian serves as the lingua franca of the city. It is the native language of Herat and the local dialect – known by natives as Herātī – belongs to the Khorāsānī cluster within Persian. It is akin to the Persian dialects of eastern Iran, notably those of Mashhad and Khorasan Province. The second language that is understood by many is Pashto, which is the native language of the Pashtuns. The local Pashto dialect spoken in Herat is a variant of western Pashto, which is also spoken in Kandahar and southern and western Afghanistan. Religiously, Sunni Islam is practiced by the majority while Shias make up the minority.

The city once had a Jewish community. About 280 families lived in Herat as of 1948 but most moved to Israel that year, and the community disappeared by 1992. There are four former synagogues in the city's old quarter, which were neglected but in the late 2000s renovated by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, three of them turning into nurseries and schools. The Jewish cemetery is being taken care of by Jalilahmed Abdelaziz.[42]

Culture

Notable people from Herat

- Tahir ibn Husayn 9th century Abbasid Caliphate army general, and the founder of Tahirid dynasty

- Qutb Shah ancestor of the Awans a famous (general) in the army of Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi in late 10th, early 11th century.

- Khwājah Abdullāh Ansārī, a famous Persian poet of the 11th century

- Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad, was the emperor of the Ghurid dynasty from 1163 to 1202. During his reign, the Ghurid dynasty became a world power, which stretched from Gorgan to Bengal

- Taftazani, a famous Muslim polymath of the 14th century

- Nūr ud-Dīn Jāmī, a famous Persian Sufi poet of the 15th century

- Hatefi, a Persian poet of the 16th century and nephew of Nūr ud-Dīn Jāmī

- Nizām ud-Din ʿAlī Shīr Navā'ī, famous poet and politician of the Timurid era

- Fakhr ad-Din ar-Razi, famous theologian and philosopher the twelfth century

- Ustād Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, the greatest of the medieval Persian painters

- Gowharšād, wife of Shāhrūkh Mīrzā

- Mīrzā Shāhrūkh bin Tīmur Barlas, Emperor of the Timurid dynasty of Herāt

- Mīrzā Husseyn Bāyqarāh, Emperor of the Timurid dynasty of Herāt

- Ali al-Qari, from 17th century, considered to be one of the masters of hadith and Imams of fiqh

- Shāh Abbās The Great, Emperor of Safavid Persia

- Alka Sadat, Film producer was born here[43]

- Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of the Durrani Empire in 1747

- Latif Nazemi, famous poet of modern times

- Sultan Jan, ex-ruler of Herat.

- Ismail Khan, former governor of Herat Province and Minister of Water and Energy

- Sonita Alizadeh, international rapper.

- Ali-Shir Nava'i, 15th century Chagatai poet

- Behzad Nikzad, former head data scientist of Overbond and author

Economy and infrastructure

Transport

Air

Herat International Airport was built by engineers from the United States in the 1960s and was used by the Soviet Armed Forces during the Soviet–Afghan War in the 1980s. It was bombed in late 2001 during Operation Enduring Freedom but had been rebuilt within the next decade. The runway of the airport has been extended and upgraded and as of August 2014 there were regularly scheduled direct flights to Delhi, Dubai, Mashad, and various airports in Afghanistan. At least five airlines operated regularly scheduled direct flights to Kabul.

Rail

Rail connections to and from Herat were proposed many times, during The Great Game of the 19th century and again in the 1970s and 1980s, but nothing came to life. In February 2002, Iran and the Asian Development Bank[44][45] announced funding for a railway connecting Torbat-e Heydarieh in Iran to Herat. This was later changed to begin in Khaf in Iran, a 191 km (119 mi) railway for both cargo and passengers, with work on the Iranian side of the border starting in 2006.[46][47] Construction is underway in the Afghan side and it is estimated to be completed by March 2018.[48] There is also the prospect of an extension across Afghanistan to Sher Khan Bandar.

Road

The AH76 highway connects Herat to Maymana and the north. The AH77 connects it east towards Chaghcharan and north towards Mary in Turkmenistan. Highway 1 (part of Asian highway AH1) links it to Mashhad in Iran to the northwest, and south via the Kandahar–Herat Highway to Delaram.

Gallery

- Notable places in Herāt

Landmark at a traffic circle

Landmark at a traffic circle Mausoleum of Mirwais Sadiq Khan, son of Ismail Khan, who was killed in 2004 in clashes with the Afghan National Army

Mausoleum of Mirwais Sadiq Khan, son of Ismail Khan, who was killed in 2004 in clashes with the Afghan National Army- Shopping center

Pol-e Mālān, a historical bridge

Pol-e Mālān, a historical bridge Remains of the Musallah complex

Remains of the Musallah complex Pillar of Musallah Complex

Pillar of Musallah Complex Khwājah Abdullāh Ansārī shrine, a Sufi of the 11th century

Khwājah Abdullāh Ansārī shrine, a Sufi of the 11th century Gazar Gah cemetery

Gazar Gah cemetery- Tomb of Jāmi, a poet of the 15th century

The Jewish cemetery

The Jewish cemetery View of Herat from a hill

View of Herat from a hill

Herat in fiction

- The beginning of Khaled Hosseini's 2007 novel A Thousand Splendid Suns is set in and around Herāt.

- Salman Rushdie's novel The Enchantress of Florence makes frequent reference to events in Herāt in the Middle Ages.

Sister cities

See also

References

- ↑ http://samuelhall.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/State-of-Afghan-Cities-2015-Volume_1.pdf

- 1 2 3 "Settled Population of Herat province by Civil Division, Urban, Rural and Sex-2012-13" (PDF). Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Central Statistics Organization. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ↑ Herat - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-webster.com (2012-08-31). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ḥamd-Allāh Mustawfī of Qazwīn (1340). "The Geographical Part of the NUZHAT-AL-QULŪB". Translated by Guy Le Strange. Packard Humanities Institute. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- 1 2 3 Singh, Ganda (1959). Ahmad Shah Durrani, father of modern Afghanistan. Asia Publishing House, Bombay. (PDF version 66 MB Archived February 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Daniel Wagner and Giorgio Cafiero: The Paradoxical Afghan/Iranian Alliance. In: The Huffington Post: 11/15/2013.

- ↑ "Bomb blast hits west Afghan city". BBC News. August 3, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ↑ "The State of Afghan Cities 2015, Volume 2". Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ↑ Hughes, Roland (4 August 2016). "Do tourists really go to Afghanistan?" – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Translated by Herbert Cushing Tolman. "The Behistan Inscription of King Darius". Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

- ↑ electricpulp.com. "HERAT ii. HISTORY, PRE-ISLAMIC PERIOD – Encyclopædia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- ↑ An Historical Guide to Kabul – The Story of Kabul by Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād.

- ↑ The earliest recorded date of a bishop in Herat is 424. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2011-04-01.

- ↑ Abu Ja’far Muḥammad ibn Jarir Ṭabari, Taʾrikh al-rosul wa’l-moluk, pp. 2904-6

- ↑ Warfare in Chinese History. Brill. 2000. p. 118.

- ↑ Dupree, Nancy Hatch (1970). An Historical Guide to Afghanistan. First Edition. Kabul: Afghan Air Authority, Afghan Tourist Organization. p. 492. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- 1 2 3 Skrine, Francis Henry; Ross, Edward Denison (2004). The heart of Asia: a history of Russian Turkestan and the Central Asian Khanates from the earliest times. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 0-7007-1017-5.

- ↑ Musée du Louvre, Calligraphy in Islamic Art Archived 2011-11-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Brill Publishers, Vol.3: H-Iram, 1986, Leiden, pp. 177

- ↑ Eṣṭaḵri, pp. 263-65, tr. pp. 277-82

- ↑ Ibn Ḥawqal, pp. 437-39, tr. pp. 424;

- ↑ Moqaddasi (Maqdesi), Aḥsan al-taqāsim fi maʿrifat al-aqālim, ed. M. J. de Goeje, Leiden, 1906, p. 307;

- ↑ Azerbaycan :: Karakoyunlu devleti. Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Savory, Roger (2 January 2007). "The Safavid state and polity". Iranian Studies. 7 (1–2): 206. doi:10.1080/00210867408701463.

Herat is referred to as a'zam-i bilād-i īrān (the greatest of the cities of Iran) and Isfahan as khulāsa-yi mulk-i īrān (the choicest part of the realm of Iran).

- ↑ Szuppe, Maria. "HERAT iii. HISTORY, MEDIEVAL PERIOD". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles, eds. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7): From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 183, 394–395. ISBN 978-0521200950.

- ↑ Revolution Unending: Afghanistan, 1979 to the Present by Gilles Dorronsoro, 2005

- ↑ Joes, Anthony James (18 August 2006). "Resisting Rebellion: The History and Politics of Counterinsurgency". University Press of Kentucky – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Failings of Inclusivity: The Herat uprising of March 1979 - Afghanistan Analysts Network". www.afghanistan-analysts.org.

- ↑ Afghanistan: The First Five Years of Soviet Occupation, by J. Bruce Amstutz – Page 133 & 145

- ↑ War, Exile and the Music of Afghanistan: The Ethnographer's Tale by John Baily

- ↑ https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/eoir/legacy/2014/01/16/Af_chronology_1995-.pdf

- ↑ "More arrests after Herat killing". London: BBC News. 2004-03-25.

- ↑ Motlagh, Jason.Iran's Spending Spree in Afghanistan. Time. Wednesday May 20, 2009. Retrieved on May 24, 2009.

- ↑ "U.S. Ambassador Karl W. Eikenberry Remarks at the Lease-Signing Ceremony for U.S. Consulate Herat" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Herat Climate Normals 1959-1983". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ↑ Bendeich, Mark (June 25, 2007). "Cars, Not War, Threaten Afghan Minarets". Islam Online. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ↑ Podelco, Grant (July 18, 2005). "Afghanistan: Race To Preserve Historic Minarets of Herat, Jam". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ↑ A good description of the sites, including former afgahani jews who lived there, and of some locals, could be seen at "Quest for the lost tribes", a film by Simcha Jacobovici.

- ↑ "Welcome – Naval Postgraduate School" (PDF). www.nps.edu.

- ↑ "2003 National Geographic Population Map" (PDF). Thomas Gouttierre, Center For Afghanistan Studies, University of Nebraska at Omaha; Matthew S. Baker, Stratfor. National Geographic Society. 2003. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ↑ "Relics of old Afghanistan reveal Jewish past". 24 June 2009 – via Reuters.

- ↑ Alka Sadat Archived 2016-06-25 at the Wayback Machine., womensvoicesnow.org, Retrieved 7 June 2016

- ↑ Khaf-Herat railway, http://www.raillynews.com/2013/khaf-herat-railway/

- ↑ afghanistan railways, 2014, http://www.andrewgrantham.co.uk/afghanistan/railways/iran-to-herat/

- ↑ "Iran to Herat railway – Railways of Afghanistan". www.andrewgrantham.co.uk.

- ↑ Opening up Afghan trade route to Iran Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine. Railway Gazette International 2008-01-29

- ↑ "Rail Linkup With Afghanistan by March 2018". 25 February 2017.

- ↑ columnist, Erin Grace / World-Herald. "Grace: Afghans arrive to embrace sister city Bluffs and to share their passion and hope".

![]()

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Herat. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Herat. |

- Video: Herat After Transition, with Voiceover by Natochannel

- Heratonline.com: Information and news about Herāt

- Detailed map of Herāt city

- Map of Herāt and surroundings in 1942, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin

- Explore Herat with Google Earth on Global Heritage Network

- Herat a leading city in Afghanistan

- Photo Gallery of Herat

- Three Women of Herat: A Memoir of life, Love and Friendship in Afghanistan" by Veronica Doubleday

- Ethnomusicological Research in Afghanistan:

- ArchNet.org. "Herat". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Archived from the original on 2012-10-26.

| Preceded by Samarkand |

Capital of Timurid dynasty 1505–1507 |

Succeeded by - |

.