Burusho people

.jpg) A group of Burusho women in the Hunza Valley, Pakistan | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 87,000 (2000) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

Chitral District, Hunza (Pakistan) | |

| Languages | |

| Burushaski, Khowar[1] | |

| Religion | |

| Ismaili Islam, historically Shamanism, Buddhism, Hinduism[2] |

The Burusho or Brusho, also known as the Hunza people or Botraj,[3][4] live in Hunza, Nagar, Chitral, and in valleys of Gilgit–Baltistan in northern Pakistan,[5] as well as in Jammu and Kashmir, India.[4][6] All of them are Ismaili Muslims and preserve their ethnic traditions. Their language, Burushaski, has been classified as a language isolate.[7] Although their origins are unknown, it is likely that the Burusho people "were indigenous to northwestern India (current day Pakistan) and were pushed into their present homeland by the movements of the Indo-Aryans," who migrated to the subcontinent in 1800 B.C.[8]

Hunza

The historical area of Hunza and present northern Pakistan has had, over the centuries, mass migrations, conflicts and resettling of tribes and ethnicities, of which the Dardic Shina race is the most prominent in regional history. People of the region have recounted their historical traditions down the generations.

Historic Hunza hosts four major yet genealogically diverse clans that trace their paterlineal ancestry (according to tradition) to varying ethnics groups. The Khurukutz are said to be related to the communities now settled in the Gojal-Pamir border region. The Buroong are said to have migrated up from the Indus region. Diramiting and Barataling trace their roots to the Balkan/East European ethnic diaspora.

Besides clans, Burusho society is divided into classes, including the Thamo royals; the Wazir family governing the state; Trangfa and Akabirting village leaders; Bare and Sis combat fighters; Baldakuyos carriers; and Bericho musicians. An offshoot of Bericho migrated to the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. Hunza people are predominantly Shia Muslims of the Nizari Ismaili tradition.

Hunzakuts and the Hunza region have relatively high literacy compared to most other districts in Pakistan. Hunza is a major tourist attraction in Pakistan, and many domestic and foreign tourists travel there to enjoy its stunning mountain landscape. The district has many modern amenities and is advanced by Asian standards. Local legend states that Hunza may have been associated with the lost kingdom of Shangri-La.

The longevity of Hunza people has been noted by some,[11] but others refute this as a longevity myth and cite a life expectancy of 110 years for men and 122 for women with a high standard deviation.[12] There is no evidence that Hunza life expectancy is significantly above the average of poor, isolated regions of Pakistan. Claims of health and long life were almost always based solely on the statements by the local mir (king). An author who had significant and sustained contact with Burusho people, John Clark, reported that they were overall unhealthy.[13]

Clark and Lorimer reported frequent violence and starvation in Hunza.[14] Popular claims of the Hunza diet have been exposed as pseudoscience, while the mythology surrounding the Hunza people is noble savage stereotyping.

Upper Hunza, locally called Gojal, is inhabited by people whose ancestors moved up from proper Hunza to irrigate and defend the borders with China and Afghanistan. They speak a dialect called Wakhi, which is influenced by Brushahski and Pamiri languages due to the closeness and contact with these mountain communities. The Shina-speaking people live in the southern Hunza. They have come from Chilas, Gilgit, and other Shina-speaking areas of Pakistan.

Jammu and Kashmir

The Burusho people also reside in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, being mainly concentrated in Batamalu, as well as in Botraj Mohalla, which is southeast of Hari Parbat.[4] This Burusho community is descended from two former princes of the British Indian princely states of Hunza and Nagar, who with their families, migrated to this region in the 19th century A.D.[4] They are known as the Botraj by other ethnic groups in the state,[4] and practice Shiite Islam.[15] Arranged marriages are customary.[16]

Since the partition of India in 1947, the Indian Burusho community have not been in contact with the Pakistani Burusho.[17] The Government of India has granted the Burusho community Scheduled Tribe status, as well as reservation, and therefore, "most members of the community are in government jobs."[4][15] The Burusho people of India speak Burushashki, also known as Khajuna, and their dialect, known as Jammu & Kashmir Burushashski (JKB), "has undergone several changes which make it systematically different from other dialects of Burushaski spoken in Pakistan".[15] In addition, many Jammu & Kashmiri Burusho are multilingual, also speaking Kashmiri and Hindustani, as well as Balti and Shina to a lesser extent.[15]

Genetics

A variety of Y-DNA haplogroups are seen among certain random samples of people in Hunza. Most frequent among these are R1a1 and R2a, which probably originated in either South Asia,[18][19] [20][21] [22][23] Central Asia[24][25] or Iran and Caucasus.[26][27] R2a, unlike its extremely rare parent R2, R1a1 and other clades of haplogroup R, is now virtually restricted to South Asia. Two other typically South Asian lineages, haplogroup H1 and haplogroup L3 (defined by SNP mutation M20) have also been observed from few samples.[28][25]

Other Y-DNA haplogroups reaching considerable frequencies among the Burusho are haplogroup J2, associated with the spread of agriculture in, and from, the neolithic Near East,[24][25] and haplogroup C3, of Siberian origin and possibly representing the patrilineage of Genghis Khan. Present at lower frequency are haplogroups O3, an East Eurasian lineage, and Q, P, F, and G.[25] DNA research groups the male ancestry of some of the Hunza inhabitants with speakers of Pamir languages and other mountain communities of various ethnicites, due primarily to the M124 marker (defining Y-DNA haplogroup R2a), which is present at high frequency in these populations.[29] However, they have also an East Asian genetic contribution, suggesting that at least some of their ancestry originates north of the Himalayas.[30]

While genetic evidence supports a 2% Greek genetic component among the Pashtun ethnic group of South Asia,[31] it does not support any for the Burusho.[32]

Influence in the Western world

Healthy living advocate J. I. Rodale wrote a book called The Healthy Hunzas in 1955 that asserted that the Hunzas, noted for their longevity and many centenarians, were long-lived because they consumed healthy organic foods, such as dried apricots and almonds, and had plenty of fresh air and exercise.[33] He often mentioned them in his Prevention magazine as exemplary of the benefits of leading a healthy lifestyle. Since the opening per se of the state of Hunza to Pakistan and rest of the world, the diet that almost exclusively consisted of organically grown fruits and vegetables, oils, and seasonings grown in the immediate localities is now dominated by extensive trade with neighboring China and Pakistan. Subsequently, much processed modern and even GMO food products have reached this remote habitation. Some alternative health advocates claim that GMO infiltration may be negatively impacting their life expectancy.

Dr. John Clark stayed among the Hunza people for 20 months and in his book Hunza - Lost Kingdom of the Himalayas[34] writes: "I wish also to express my regrets to those travelers whose impressions have been contradicted by my experience. On my first trip through Hunza, I acquired almost all the misconceptions they did: The Healthy Hunzas, the Democratic Court, The Land Where There Are No Poor, and the rest—and only long-continued living in Hunza revealed the actual situations". Regarding the misconception about Hunza people's health, Clark also writes that most of his patients had malaria, dysentery, worms, trachoma, and other health conditions easily diagnosed and quickly treated. In his first two trips he treated 5,684 patients.

Furthermore, Clark reports that Hunza do not measure their age solely by calendar (metaphorically speaking, as he also said there were no calendars), but also by personal estimation of wisdom, leading to notions of typical lifespans of 120 or greater.

The October 1953 issue of National Geographic had an article on the Hunza River Valley that inspired Carl Barks' story Tralla La.[35]

Renée Taylor wrote several books in the 1960s, treating the Hunza as a long-lived and peaceful people.[36]

See also

References

- ↑ "TAC Research The Burusho". Tribal Analysis Center. 30 June 2009. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- ↑ Archived 5 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Berger, Hermann (1985). "A survey of Burushaski studies". Journal of Central Asia. 8 (1): 33–37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ahmed, Musavir (2016). "Ethnicity, Identity and Group Vitality: A study of Burushos of Srinagar". Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies. 3 (1): 1–10. ISSN 2149-1291.

- ↑ "Jammu and Kashmir Burushaski : Language, Language Contact, and Change" (PDF). Repositories.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ↑ Gordon, Raymond G. Jr., ed. (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ↑ "Burushaski language". Encyclopædia Britannica online.

- ↑ West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 9781438119137.

Another, more likely origin story, given the uniqueness of their language, proclaims that they were indigenous to northwestern India and were pushed into their present homeland by the movements of the Indo-Aryans, who traveled southward sometime around 1800 B.C.E.

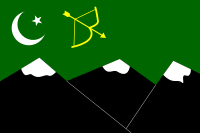

- ↑ "Hunza". Flags of the World. 7 June 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ "Flag Spot Hunza (Pre-independence Pakistan)". Flagspot.net.

- ↑ Wrench, Dr Guy T (1938). The Wheel of Health: A Study of the Hunza People and the Keys to Health. 2009 reprint. Review Press. ISBN 978-0-9802976-6-9. Retrieved 12 August 2010

- ↑ Tierney, John (29 September 1996). "The Optimists Are Right". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Hunza - The Truth, Myths, and Lies About the Health and Diet of the "Long-Lived" People of Hunza, Pakistan, Hunza Bread and Pie Recipes". www.biblelife.org.

- ↑ Allan, Nigel J. R. (16 July 1990). "Household Food Supply in Hunza Valley, Pakistan". Geographical Review. 80 (4): 399–415. doi:10.2307/215849. JSTOR 215849.

- 1 2 3 4 Munshi, Sadaf (2006). Jammu and Kashmir Burushashki: Language, Language Contact, and Change. The University of Texas at Austin. pp. 4, 6-.

- ↑ Hall, Lena E. (28 October 2004). Dictionary of Multicultural Psychology: Issues, Terms, and Concepts. SAGE. p. 12. ISBN 9781452236582.

Among the Burusho of India, the parents supposedly negotiate a marriage without consulting the children, but often prospective brides and grooms have grown up together and know each other well.

- ↑ Ahmed, Musavir (2016). "Ethnicity, Identity and Group Vitality: A study of Burushos of Srinagar". Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies. 3 (1): 1–10. ISSN 2149-1291.

The community has no contact with their Burushos of Gilgit-Baltistan since 1947, when partition of India and Pakistan necessitated the division of the erstwhile princely state of Kashmir. No participant was ready to move to Hunza/Nagar if provided a chance.

- ↑ Kivisild, T.; et al. (2003), "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations", The American Journal of Human Genetics, 72 (2): 313–32, doi:10.1086/346068, PMC 379225, PMID 12536373

- ↑ Sahoo, S.; et al. (2006), "A prehistory of Indian Y chromosomes: Evaluating demic diffusion scenarios", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103 (4): 843–8, Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..843S, doi:10.1073/pnas.0507714103, PMC 1347984, PMID 16415161

- ↑ Sengupta, Sanghamitra; et al. (2006). "Polarity and Temporality of High-Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal Minor Genetic Influence of Central Asian Pastoralists". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 78 (2): 202–21. doi:10.1086/499411. PMC 1380230. PMID 16400607.

- ↑ Sharma, Swarkar; et al. (2009). "The Indian origin of paternal haplogroup R1a1* substantiates the autochthonous origin of Brahmins and the caste system". Journal of Human Genetics. 54 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1038/jhg.2008.2. PMID 19158816.

- ↑ Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; et al. (2010). Cordaux, Richard, ed. "The Influence of Natural Barriers in Shaping the Genetic Structure of Maharashtra Populations". PLoS ONE. 5 (12): e15283. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515283T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015283. PMC 3004917. PMID 21187967.

- ↑ Thanseem, Ismail; et al. (2006). "Genetic affinities among the lower castes and tribal groups of India: Inference from Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA". BMC Genetics. 7: 42. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-7-42. PMC 1569435. PMID 16893451.

- 1 2 R. Spencer Wells et al., "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (28 August 2001).

- 1 2 3 4 Firasat, Sadaf; Khaliq, Shagufta; Mohyuddin, Aisha; Papaioannou, Myrto; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Underhill, Peter A; Ayub, Qasim (2006). "Y-chromosomal evidence for a Albanian contribution to the Pathan population of Pakistan". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (1): 121–6. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201726. PMC 2588664.

- ↑ Underhill 2014.

- ↑ Underhill 2015.

- ↑ Raheel, Qamar; et al. (2002). "Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan". American Journal of Human Genetics. 70: 1107–1124. doi:10.1086/339929.

- ↑ R. Spencer Wells et al., The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

- ↑ Li, Jun Z. "Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome wide patterns of variation". Science. 319: 1100–1104. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1100L. doi:10.1126/science.1153717.

- ↑ Y-chromosomal evidence for a limited Greek contribution to the Pathan population of Pakistan Archived 20 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine., European Journal of Human Genetics (2007) 15; published online 18 October 2006

- ↑ Qamar, R; Ayub, Q; Mohyuddin, A; et al. (May 2002). "Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70: 1107–24. doi:10.1086/339929. PMC 447589. PMID 11898125.

- ↑ Rodale, J. I. The Healthy Hunzas 1955

- ↑ Clark, John (1956). Hunza - Lost Kingdom of the Himalayas (PDF). New York: Funk & Wagnalls. OCLC 536892.

- ↑ The Carl Barks Library Volume 12, page 229

- ↑ Taylor, Renée (1964). Long Suppressed Hunza health secrets for long life and happiness. New York: Award Books.

Bibliography

- Underhill, Peter A. (2014), "The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a" (PDF), European Journal of Human Genetics, 23 (1): 124–131, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.50, ISSN 1018-4813, PMC 4266736, PMID 24667786, retrieved 15 June 2016

- Underhill, Peter A. (2015), "The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a", European Journal of Human Genetics, 23: 124–131, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.50, PMC 4266736, PMID 24667786